Abstract

A need for social support is often expressed after hospitalization post HSCT. Emotional support and positive psychological constructs play an important role in post-HSCT recovery. Interventions generating positive affect can influence the health and well-being of transplant patients. It has been established that coaching in elite sport area leads to performance by playing a decisive role in maintaining the athlete’s feelings of hope and autonomy in order to enable him or her to achieve their goals. In this single-center, prospective, one-arm study, we evaluated, in 32 post-HSCT patients, the acceptability of a coaching program inspired by elite sport coaching. Benefits were evaluated by questionnaires and semi-structured interviews. The coaching program was accepted by 97% of the patients. Analysis of the scores on the “Means” sub-dimension of Hope showed a significant increase over time (p = 0.0249 < 0.05) for every patient. Qualitative analysis of patient’s satisfaction pointed out that this support facilitated the transition to a life without illness in particular in the non-hospital context of coaching sessions. Our results show that a “sport-inspired coaching“ may offer an innovative approach supporting psychological and social recovery after HSCT and helping to start and/or maintain the processes leading to psychological well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) often represents the only possibility of cure for patients with poor prognosis hematological malignancies [1,2,3]. The therapeutic course is a difficult journey with long periods of hospitalization and social isolation. During this timeframe, patients are exposed to many complications (e.g., graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), infections, etc.), sources of subsequent deaths or quality of life impairment in surviving patients. When the initial storm is over, patients may suffer the physical sequelae of their disease and treatments and also become more preoccupied with their future: fear of recurrence, reduced self-esteem, morbid preoccupation with death, sense of abandonment, social isolation, difficulty in reconnecting with familial, occupational and social networks [4,5,6]. The prevalence of depression, more widespread than after any other treatments [7], increases when concerns about the initial disease fade away and keeps evolving for a long time after transplantation [8, 9], possibly compromising the patient’s full recovery [10]. Even more, relationships between this depressive status and reduced survival have been documented among transplant patients [11, 12]. Nowadays, many health-care programs have identified this reality and have developed access to psychologic support within holistic supportive care access. However, despite the presence of intense emotional distress and the identified needs, fewer than 10% of transplant patients follow a psychotherapeutic program [13,14,15]. Moreover, the absence of social support when leaving the hospital complicates everyday life [16] and the resumption of social or occupational activity [3, 13].

The development of different psychosocial support should therefore be investigated for helping transplant patients quickly recover a reasonable quality of life after their treatment. Emotional support is known to play an important role in post-HSCT survival [17], and some psychosocial factors (low anxiety level, “fighting spirit”, high quality of life) have positive consequences for survival [18]. Moreover, recent studies have shown that positive psychological constructs (e.g., optimism, hope, perseverance) were associated with improved quality of life and other health outcomes [19]. It, therefore, seems necessary, beyond hospitalization, to offer supportive care and interventions that generate positive effects to influence the health and well-being of transplant patients [19, 20]. In this regard, coaching, as a personalized form of social support, has given evidence of its efficacy [21, 22]. Individualized intervention is more effective than group [23] or traditional social support interventions [24], especially in reducing the onset of depression- and anxiety-related symptoms and in improving the long-term quality of life [25]. In the post-treatment recovery period, coaching can be seen as a tool facilitating the transition to a post-cancer life [26]. We proposed to test the effectiveness of a coaching program inspired by the one developed to help elite athletes achieve performance. The literature shows that performance coaching requires the development of motivational strategies to keep the athlete’s feelings of hope, autonomy, and competence intact throughout the process of achieving athletic goals [27]. Through a complementary and cohesive relationship, the coach works with the athlete to overcome inner barriers to achieve athletic performance and psychological well-being [28, 29].

This monocentric pilot study proposes to evaluate the acceptability of a “sport-inspired coaching” for patients in post-HSCT remission. Our general hypothesis is that the program could offer an innovative approach supporting psychological and social recovery after cancer and helping to start-up and/or maintain processes leading to psychological well-being [30].

Patients and methods

Eligibility criteria

Patients were eligible if they had received an allogeneic HSCT at least three months earlier, could speak and read French, and had signed an informed consent form. Patients could not be included if they presented an active GvHD, suffered from a progression of their hematological disease or presented with an active clinical or psychological complication needing active treatment. People unable to give their consent, or unable to follow the trial for geographical, social, or psychological reasons were not included. Thirty-two eligible adults patients were included in the study.

The study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03272789) was approved by the institutional and ethical review boards and the “Agence nationale de sécurité du medicament” (ANSM).

Objectives

The main objective was to evaluate the acceptability of the intervention proposal by patients. The secondary goals concerned evaluation, through interviews and questionnaires, of the improvement in the patients’ psychological well-being after the coaching sessions.

Intervention

Coaching procedure

Coaching sessions took the form of face-to-face interviews over a period of up to six months. They were conducted by a specific coach (PD), member of the research team who has no medical background but with an expertise in coaching elite athletes as he prepared athletes for the Olympic Games (1996–2016) and was part of the French delegation to the 1996 and 2000 Olympic Games . Interviews took place in the Sports Sciences Faculty, away from the hospital. Their frequency was co-determined by the coach and the participant and depended on the latter’s needs. Sessions were spaced at least a month apart. The coaching technique was based on the motivational interview [31] which engages the coachee in a process of change through the use of open-ended questions, reformulation, active and reflective listening, and positive reinforcement. For confidentiality, the content of the sessions was not communicated to the researchers.

Data collection

Time points protocol is shown in the supplementary table.

Qualitative

Patients were questioned after coaching sessions in individual face-to-face semi-directive interviews with one of the researchers. Interviews to study the impact of the support program were scheduled (1) before the first session, (2) just after it, and (3) after the last session. The questions addressed satisfaction with the program, perception of its general characteristics (schedule, perception of the “sport coaching”), its consequences for the patient’s well-being, the envisaged or initiated changes in behavior at the end of the program, and the relations established with the coach during the intervention.

Quantitative

To evaluate the effects of the coaching and measure recovery progress. Questionaires were handed out or sent out and completed by the participants before the first session (M0) and in the course of M3, M6, and M12.

Psychosocial measurements

French-validated questionnaires were used to measure variables assessing psychological well-being [32] (self-efficacy, hope, global motivation, and quality of interpersonal relations).

-

The Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale [33, 34] evaluates individuals’ perception of their capacity to perform well in a wide range of contexts. The scale consists of 10 statements evaluated on a Likert-type scale from 1 to 4.

-

The Adult Dispositional Hope Scale [35, 36] evaluates the perceived capacity to find the means to achieve the desired goals and to motivate oneself through one’s agency to use those means [37]. The scale consists of 12 statements evaluated on a Likert scale from 1 to 8. There are two subscales: a measure of the individual’s belief in his/her capacity to achieve his/her goals (‘Belief’), and a measure of his/her ability to find a variety of means to achieve them (‘Means’).

-

The Global Motivation Scale [38] evaluates the global motivation that people have when they do things in general in their lives. It measures seven constructs: intrinsic motivation (to know, to accomplish, and to experience stimulation), extrinsic motivation (external, identified, and introjected regulation), and motivation [39, 40]. It consists of 28 items (four for each construct) evaluated on a Likert scale from 1 to 7.

-

The Quality of Interpersonal Relationships Scale [41] measures the quality of the interpersonal relationships that people may have in different spheres of their lives. Five subscales evaluate relationships in different spheres (family, friends, love partner, classroom peers, people in general) on a Likert scale from 1 to 4. This scale makes it possible to consider each sphere independently of the others. For the purposes of this study, we did not consider the sphere “classroom peers”.

Methodology and Statistics

This monocentric and prospective single-arm study followed Simon’s optimal two-stage design [42] aimed at assessing the acceptability of the sport-inspired coaching program for patients after HSCT. The primary endpoint was the acceptance rate of the program offered by patients. The main analysis tested the null hypothesis that the primary endpoint is significantly above a 50% threshold using an exact unilateral test for binary proportions with 5% error risk. According to Simon’s sample size criteria, a total of 32 patients was planned to be recruited to achieve 90% power to reject the null hypothesis assuming a real proportion equal to 75%. Secondary endpoints were the overall number of coaching sessions attended, the completion rates of the self-administered questionnaire at each visit, and the changes from values assessed before the first coaching session for each specific psychological well-being scale over time. Changes from the baseline of the different scores were analyzed using a linear mixed model.

The principal criterion of the study was the patients’ rate of acceptance of the offered program, measured by the empirical proportion of patients completing their first session with the coach, and was estimated by the proportion observed and its exact bilateral 90% confidence interval [43]. The secondary criteria were the number of coaching sessions attended, the self-administered questionnaire completion rates at each visit, and changes in questionnaire scores over time (see supplementary material for a detailed explanation of the statistical analyses). Qualitative data were obtained from the semi-structured interviews. All interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed by inductive qualitative analysis using the NVivo 12 software [44] on the methodological basis of framework analysis used in applied disciplinary fields and leading to coding by category [44].

Results

As planned per protocol, a total of 32 patients, including 14 men (43.75%) and 18 women (56.25%) with a median age of 53 years [range, 23–72] (Table 1), was included in the study at a median of 7 (4–24) months post-transplant. Main patients, diseases, and transplant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Of note, the median number of psychological consultations over transplant course prior to inclusion was 4 [range 0.00–15.00].

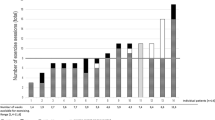

The participant flow chart is presented in Fig. 1. Of the 32 included patients, 3 patients did not attend the first coaching session: two for disease-related reasons and one on the patient’s decision. The main hypothesis, H0: p ≤ 50%, was rejected with a high significant evidence level (p < 0.0001). Analyses of secondary endpoints were carried out on the 29 remaining patients. Twenty-four (82.7%) patients completed the study. Reasons for premature discontinuations (n = 5) were the patient’s decision (n = 3), the impact of pandemic (n = 1), and the physician’s decision (n = 1) respectively. Figure 2 shows the completion rate of the self-administered questionnaires between 100% and 70.4% from M0 to M12. The results revealed the maintenance of a high completion rate (>70%) at M3, M6, and M12. In addition, the median number of sessions completed was 2 [range 1–4] for the patients who completed the first coaching session (n = 29).

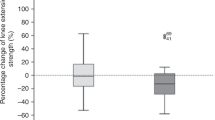

Random regression analysis of the scores per patient over time showed no significant differences in scores on the self-efficacy questionnaire, in scores on the questionnaire assessing all dimensions of global motivation, in scores on the interpersonal relationship quality questionnaire, and in scores on the questionnaire assessing the “Beliefs” sub-dimension of the Hope scale. By contrast, random regression analysis of the scores on the “Means” sub-dimension of Hope showed a significant increase over time per patient (p = 0.0249 < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Several specific themes emerged from interview analysis, mainly concerning the emergence of needs during and after treatment, the intervention design, and the perceived psychosocial impacts of the program. Table 2 describes the themes and provides quotes from the interviews.

The interviews indicated a wish for social support complementary to the psychological monitoring delivered during treatment. This coaching program is seen as a bridge making it possible to calmly envisage the future because it enables feeling supported and resuming social relations.

According to the patients, the non-hospital and sportive contexts and the sport-like character made it a special, distinctive, and therefore attractive form of support.

Participation in the program seems to have had emotional, psycho-cognitive, and conative consequences. From the first meeting, the patients reported an improvement in emotional well-being which could lead to reduced anxiety about their illness. As the sessions proceeded, they became aware of sub-optimal functioning and made changes in belief about themselves. They acknowledged that the program opened paths that they would not have imagined and gave them the opportunity to turn their intentions into reality by activating themselves and returning to positive social functioning.

Discussion

The results of this exploratory study showed that a sports-inspired coaching support proposal outside of a hospital structure and offered to an eligible patient population 6 months after transplantation (n = 32) was conceivable and well accepted since 90% of them attended the first session and more than 70% of the evaluation questionnaires were completed and returned on each occasion. These results confirmed the interest aroused. Moreover, all patients who completed the coaching sessions expressed satisfaction with this support. This satisfaction concerned three points and is illustrated in many quotes from patients (Table 2).

First, the coaching program was seen as a support facilitating the transition to a life without illness and was experienced not as an additional burden but as an unexpected bonus, meeting a need for psychosocial support needs often expressed by transplant patients [16, 45]. Six months after transplant, despite an arduous treatment and constraining post-transplant follow-up, this need was high enough to push patients to join the program [15]. It is an important element as studies have shown that depressive disorders develop more in the long-term [7,8,9] and can compromise the patient’s complete recovery [10]. Facilitating access to this kind of program for patients in remission could be a way of preventing and limiting the appearance of these disorders.

The organization of coaching sessions outside of the hospital with a non-treating staff member was a second and unexpected reason for satisfaction. They were identified by the patients as a strong signal that their journey towards cure was real. It was no longer a question of talking about medical conditions but about oneself and one’s future, thinking about projects and how to achieve them, as healthy people do. Furthermore, the model of sport coaching and its symbolic impact, beyond the connection between sport and health, provides a quite wide range of metaphors offering other ways of talking about oneself and social life. This sporting context and the coach’s professional experience seem to offer a new relational space in which patients can think and talk about subjects other than those connected with their illness and its negative consequences. This “facilitating” quasi-athletic dimension in the relationship with the coach was underlined positively by the participants. They mentioned for example an ease of exchange based on a relationship experienced as balanced, symmetrical, and conducive to autonomization.

The final satisfaction was related to the various psychological impacts generated by the coaching: greater emotional well-being, a sense of being supported, awareness of non-optimal functioning, achievement of concrete projects, and sometimes a change of life philosophy. Meanwhile, our quantitative results showed a significant increase over time in the scores for the “Means” sub-dimension of the Hope scale. This evaluates individuals’ capacity to develop positive thoughts so as to find alternative solutions and achieve their goals. This effect suggests that the coaching had a positive and long-lasting impact on the self-reported feeling of hope (up to twelve months after inclusion in the protocol, when the coaching had finished).

Recent research findings in positive psychology, the science that explores the sources of psychological health and, in particular, its adaptation to illness, offer interesting insights. Questioning the impact of “positive” constructs such as positive affect, meaning, mastery, personal growth, hope, optimism, gratitude, and well-being on mental and physical health would fuel thought around the development of psychosocial interventions that promote recovery [46]. In this regard, recent research conducted on HSCT patients has shown the beneficial effect of positive psychological constructs including hope on quality of life [47] and post-transplant recovery [17, 19]. These positive psychological constructs can be taught, cultivated, and developed in the patient. Coaching could be a type of intervention particularly adapted to the promotion of positive psychological constructs, and should thus be encouraged [48, 49].

This study provided new information on the content of the social support expected during treatment: some participants expressed the wish that it be more focused on the proposal of concrete solutions to improve the emotional management of the illness experience. Other authors have underlined the pertinence–in addition to already proposed more standard psycho-oncological monitoring–of non-therapeutic assistance aimed at extracting patients from the daily routine during treatment. For example, Hoodin & Werber [18] showed that less “anxious preoccupation”, more “fighting spirit”, and better quality of life before and soon after transplant are linked to longer survival. These positive dispositions seem essential and benefit the mental health of the patient in remission.

In the near future, it would be of interest focusing on the question of the support content offered to patients and, in line with patients’ expressed needs, on its place in the organization of care and particularly during and not only after treatment, especially for HSCT patients, given the traumatic and life-threatening nature of the transplantation experience. Assessing the acceptability of such an intervention during treatment as well as measuring the coaching impacts on patients’ well-being, hope, and other post-transplant health outcomes would be critical.

The qualitative analysis enabled us to explore the benefits of the intervention and the emergence of specific needs and to draw up future protocols guided by the expanded attention given to the participants’ viewpoint. In this perspective, systematic active participation by the patients [50, 51] would make it possible to devise appropriate interventions meeting the expectations of a given population, and so maximize the potential benefits for the recipients.

Our conclusions are limited by the low number of patients and by having only one coach working in the program: we could question if his peculiar expertise and experience may not be a crucial limit to expanding this approach. In this perspective, we have recently opened a university course cursus with the aim of certifying new “onco-coaches” while addressing this question. Even if the protocol defined a rigorous patient selection, a bias remains possible. In this perspective, a multi-center, randomized controlled study with a larger number of patients is envisaged. Although this exploratory study requires to consider our quantitative results with caution, some effects can nonetheless be highlighted [52, 53]. The data collected so far are encouraging and lead us to give further consideration to the interest of developing a new relational approach to patient support in cancerology so as to respond to patients’ specific needs during and after treatment.

References

Pulte D, Castro FA, Jansen L, Luttmann S, Holleczek B, Nennecke A, et al. Trends in survival of chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients in Germany and the USA in the first decade of the twenty-first century. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9:28.

Norkin M, Wingard JR Recent advances in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. F1000Res 2017; 6. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.11233.1.

Battiwalla M, Tichelli A, Majhail NS. Long-term survivorship after hematopoietic cell transplantation: roadmap for research and care. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2017;23:184–92.

Cavro É, Bungener C, Bioy A. Le syndrome de Lazare: une problématique de la rémission. Réflexions autour de la maladie cancéreuse chez l’adulte. Rev Francoph de Psycho-Oncologie. 2005;4:74–80.

Koocher GP, O’Malley JE. The damocles syndrome: psychosocial consequences of surviving childhood cancer. McGraw-Hill, 1981.

Tross S, Holland J Psychological sequelae in cancer survivors. In: Handbook of Psychooncology: Psychological care of the patient with cancer. (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1989) pp 101-16.

Clark CA, Savani M, Mohty M, Savani BN. What do we need to know about allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors? Bone Marrow Transpl. 2016;51:1025–31.

Kuba K, Esser P, Mehnert A, Johansen C, Schwinn A, Schirmer L, et al. Depression and anxiety following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a prospective population-based study in Germany. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2017;52:1651–7.

Kuba K, Esser P, Mehnert A, Hinz A, Johansen C, Lordick F, et al. Risk for depression and anxiety in long-term survivors of hematologic cancer. Health Psychol. 2019;38:187–95.

Oberoi DV, White VM, Seymour JF, Prince HM, Harrison S, Jefford M, et al. Distress and unmet needs during treatment and quality of life in early cancer survivorship: A longitudinal study of haematological cancer patients. Eur J Haematol. 2017;99:423–30.

Loberiza FR, Rizzo JD, Bredeson CN, Antin JH, Horowitz MM, Weeks JC, et al. Association of depressive syndrome and early deaths among patients after stem-cell transplantation for malignant diseases. JCO. 2002;20:2118–26.

Norkin M, Hsu JW, Wingard JR. Quality of life, social challenges, and psychosocial support for long-term survivors after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Semin Hematol. 2012;49:104–9.

Gruber U, Fegg M, Buchmann M, Kolb H-J, Hiddemann W. The long-term psychosocial effects of haematopoetic stem cell transplantation. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2003;12:249–56.

Mosher CE, Redd WH, Rini CM, Burkhalter JE, DuHamel KN. Physical, psychological, and social sequelae following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a review of the literature. Psycho-Oncol. 2009;18:113–27.

Pichler T, Dinkel A, Marten‐Mittag B, Hermelink K, Telzerow E, Ackermann U, et al. Factors associated with the decline of psychological support in hospitalized patients with cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2019;1:1–11.

Mayer DK, Nasso SF, Earp JA. Defining cancer survivors, their needs, and perspectives on survivorship health care in the USA. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e11–e18.

Ehrlich KB, Miller GE, Scheide T, Baveja S, Weiland R, Galvin J, et al. Pre-transplant emotional support is associated with longer survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2016;51:1594–8.

Hoodin F, Weber S. A systematic review of psychosocial factors affecting survival after bone marrow transplantation. Psychosomatics 2003;44:181–95.

Amonoo HL, Barclay ME, El-Jawahri A, Traeger LN, Lee SJ, Huffman JC. Positive psychological constructs and health outcomes in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients: a systematic review. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2019;25:e5–e16.

Costanzo ES, Juckett MB, Coe CL. Biobehavioral influences on recovery following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30:S68–S74.

Kenyon M, Young F, Mufti GJ, Pagliuca A, Lim Z, Ream E. Life coaching following haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a mixed-method investigation of feasibility and acceptability. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2015;24:531–41.

Balck F, Zschieschang A, Zimmermann A, Ordemann R. A randomized controlled trial of problem-solving training (PST) for hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients: Effects on anxiety, depression, distress, coping and pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37:541–56.

Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:13–34.

Galantino ML, Schmid P, Botis S, Dagan C, Leonard SM, Milos A. Exploring wellness coaching and traditional group support for breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. Rehabilitation Oncol 2010;28:19.

Post L, Liefbroer AI. Reducing distress in cancer patients - A preliminary evaluation of short-term coaching by expert volunteers. Psycho-Oncol. 2019;28:1762–6.

Wagland R, Fenlon D, Tarrant R, Howard-Jones G, Richardson A. Rebuilding self-confidence after cancer: a feasibility study of life-coaching. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:651–9.

Mageau GA, Vallerand RJ. The coach-athlete relationship: a motivational model. J Sports Sci. 2003;21:883–904.

Gallwey WT The Inner Game of Tennis: The classic guide to the mental side of peak performance. (Pan Macmillan, 1974).

Whitmore PG. Behavioral, cognitive, or brain-based training? Perf Improv. 2004;43:9–14.

Blaise D, Calvin S, Cuvelier S, Ben Soussan P, Villaron C, Dantin P, et al. REBOUND ‘Trained to live again’: The practice of great Olympic coaches improves and enhances the quality of life of cancer patients in remission after hematopoietic stem cell allogeneic transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2020;55:997–9.

Miller WR, Rollnick S Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change, 2nd ed. (The Guilford Press: New York, NY, US, 2002).

Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:719–27.

Schwarzer, R, & Jerusalem, M (1995). Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. In J. Weinman, S Wright, & M Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: a user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). Windsor, England: NFER-NELSON.

Scholz U, Doña BG, Sud S, Schwarzer R. Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2002;18:242–51.

Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST, et al. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60:570–85.

Gana K, Daigre S, Ledrich J. Psychometric properties of the french version of the adult dispositional hope scale. Assessment 2013;20:114–8.

Snyder CR. Hope theory: rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inq. 2002;13:249–75.

Guay F, Mageau GA, Vallerand RJ. On the hierarchical structure of self-determined motivation: a test of top-down, bottom-up, reciprocal, and horizontal effects. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29:992–1004.

Deci E, Ryan RM Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. (Springer US, 1985). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7 SMASH.

Vallerand RJ, Blais MR, Brière NM, Pelletier LG. Construction et validation de l’échelle de motivation en éducation (EME). = Construction and validation of the Motivation toward Education Scale. CAN J BEH SCI. 1989;21:323–49.

Sénécal CB, Vallerand RJ, Vallières EF. Construction et validation de l’Échelle de la Qualité des Relations Interpersonnelles (EQRI). Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 1992;42:315–24.

Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:1–10.

Pope, C, & Mays, N Qualitative methods in health research. In C Pope & N Mays (Eds.), Qualitative research in health care. 3rd edn. (Blackwell Publishing; BMJ Books 2006). https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470750841.ch1

Ritchie J, Spencer L Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research. In: Huberman, AM, & Miles, MB (Eds.) The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion. (SAGE Publications: London, 2002) pp 305-29.

Khan NF, Evans J, Rose PW. A qualitative study of unmet needs and interactions with primary care among cancer survivors. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:S46–51.

Aspinwall LG, Tedeschi RG. The value of positive psychology for health psychology: progress and pitfalls in examining the relation of positive phenomena to health. Ann Behav Med. 2010;39:4–15.

Kenzik K, Huang I-C, Rizzo JD, Shenkman E, Wingard J. Relationships among symptoms, psychosocial factors, and health-related quality of life in hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:797–807.

Amonoo HL, Massey CN, Freedman ME, El-Jawahri A, Vitagliano HL, Pirl WF, et al. Psychological considerations in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychosomatics 2019;60:331–42.

Berg CJ, Vanderpool RC, Getachew B, Payne JB, Johnson MF, Sandridge Y, et al. A hope-based intervention to address disrupted goal pursuits and quality of life among young adult cancer survivors. J Canc Educ. 2020;35:1158–69.

Duffett L. Patient engagement: what partnering with patient in research is all about. Thromb Res. 2017;150:113–20.

Harrison JD, Auerbach AD, Anderson W, Fagan M, Carnie M, Hanson C, et al. Patient stakeholder engagement in research: a narrative review to describe foundational principles and best practice activities. Health Expect. 2019;22:307–16.

Lee EC, Whitehead AL, Jacques RM, Julious SA. The statistical interpretation of pilot trials: should significance thresholds be reconsidered? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:41.

Whitehead AL, Sully BGO, Campbell MJ. Pilot and feasibility studies: is there a difference from each other and from a randomized controlled trial? Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;38:130–3.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank L Caymaris, Head Nurse of the Department of Hematology, Transplant and Cellular Therapy Program for her involvement and engagement in this research project.

Funding

This study is funded by Crédit Agricole Foundation and Bouches-du-Rhône Departmental Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cuvelier, S., Blaise, D., Boher, JM. et al. A study of elite sport-inspired coaching for patients after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 56, 2755–2762 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-021-01401-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-021-01401-y

This article is cited by

-

The European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) roadmap and perspectives to improve nutritional care in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation on behalf of the Cellular Therapy and Immunobiology Working Party (CTIWP) and the Nurses Group (NG) of the EBMT

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2023)