Abstract

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the supero-lateral medial forebrain bundle (slMFB) is associated with rapid and sustained antidepressant effects in treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Beyond that, improvements in social functioning have been reported. However, it is unclear whether social skills, the basis of successful social functioning, are systematically altered following slMFB DBS. Therefore, the current study investigated specific social skills (affective empathy, compassion, and theory of mind) in patients with TRD undergoing slMFB DBS in comparison to healthy subjects. 12 patients with TRD and 12 age- and gender-matched healthy subjects (5 females) performed the EmpaToM, a video-based naturalistic paradigm differentiating between affective empathy, compassion, and theory of mind. Patients were assessed before and three months after DBS onset and compared to an age- and gender-matched sample of healthy controls. All data were analyzed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests. DBS treatment significantly affected patients’ affective responsiveness towards emotional versus neutral situations (i.e. affective empathy): While their affective responsiveness was reduced compared to healthy subjects at baseline, they showed normalized affective responsiveness three months after slMFB DBS onset. No effects occurred in other domains with persisting deficits in compassion and intact socio-cognitive skills. Active slMFB DBS resulted in a normalized affective responsiveness in patients with TRD. This specific effect might represent one factor supporting the resumption of social activities after recovery from chronic depression. Considering the small size of this unique sample as well as the explorative nature of this study, future studies are needed to investigate the robustness of these effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately 30% of patients with depression do not respond to conventional treatment methods such as psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy [1]. Resistance to antidepressant treatments is associated with a reduced quality of life for the patients [2, 3]. Currently, deep brain stimulation (DBS) is under investigation as new emerging treatment method in psychiatry [4,5,6,7]. DBS is an invasive, non-lesional and highly focal treatment method that involves the bilateral implantation of electrodes into a selected brain area as well as the constant application of electrical impulses to this brain target. Electrical current is delivered from a pulse generator implanted subcutaneously in the region of the clavicular [8]. The supero-lateral medial forebrain bundle (slMFB) represents one of the brain targets for DBS electrode placement currently investigated in treatment-resistant depression (TRD) [9, 10]. DBS of the slMFB has shown promising results in terms of rapid and sustained antidepressant effects [11,12,13,14,15]. Beyond that, patients subjectively reported social functioning improvements [13, 16]. Considering that normal social functioning is crucial for a good quality of life [17, 18], reduces the mortality risk [19] and further plays an important role in the long-term stabilization after chronic diseases [20], it can be considered an important therapeutic outcome [9]. However, slMFB DBS effects beyond symptom improvement are rarely studied [21, 22] and the mechanisms of slMFB DBS improving poor social functioning in depression are unknown, so far [20]. Thus, the current study systematically investigates DBS treatment effects on social skills, the basis of successful social functioning [23]. Specifically, three higher-order social skills termed affective empathy, compassion, and theory of mind (ToM) are being investigated. Affective empathy, compassion, and ToM were assessed behaviorally before and three months after the onset of active slMFB DBS in patients with TRD and compared to a sample of age- and gender-matched healthy controls.

Affective empathy is defined as the ability to share positive and negative feelings of a counterpart [24]. Feelings of affective empathy might further induce positive feelings of warmth and care including the motivation to help another person and reduce their suffering (compassion/ concern). Study evidence shows that patients with depressive symptoms feel less affective empathy and compassion [20, 25, 26]. On the other side, feelings of affective empathy might also cause aversive feelings of stress [27], which seem to be prominent in patients with depression [25, 28,29,30]. Theory of Mind (ToM), also known as perspective-taking or mentalizing, describes the ability to understand and infer mental states of another person [31]. Data from studies investigating ToM in depression have been inconsistent [20, 28]. Meta-analyses have yielded impaired ToM skills [32, 33], while recent single studies revealed intact ToM skills either from self-report questionnaires or assessed with new naturalistic paradigms [25, 26, 30].

Considering the role social skill deficits play in the development, maintenance and re-occurrence of depressive symptoms [34,35,36], improving these deficits represents an important outcome in the antidepressant treatment. Pharmacotherapy as well as specifically developed psychotherapy (e.g. cognitive behavioral system of psychotherapy (CBASP) [37]; interpersonal therapy (IPT) [38]) have an impact on social skill deficits in depression, but effects are only small to moderate [20, 39, 40]. DBS of the slMFB, however, might directly influence social skills. This idea is based on neuroimaging data demonstrating that the slMFB as a connecting structure of brain regions of the mesolimbic pathway not only induces brain metabolism changes in the stimulated area but also distal to the stimulated target [41,42,43]. Importantly, neuronal regions associated with affective empathy, compassion and ToM partly overlap with these regions, e.g. the medial prefrontal cortex, the ventral tegmental area and the ventral striatum [24, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. It thus seems plausible to assume that slMFB DBS modulates social skill deficits associated with depression.

In this study, we aim to illuminate social functioning changes following slMFB DBS by systematically investigating behaviorally assessed affective empathy, compassion, and ToM before and after the onset of stimulation in a unique sample of patients with TRD. In order to do so, we used a naturalistic test paradigm based on video stimuli, the EmpaToM [24]. The EmpaToM has previously been validated using an established empathy task for behavioural outcomes as well as on a neuronal level by comparison of activation clusters with previous findings of meta-analyses [24]. Furthermore, this paradigm has been shown to significantly differentiate between affective empathy, compassion and ToM in studies with different (patient) samples [53,54,55]. Patients with TRD (n = 12) performed the EmpaToM both before the neurosurgical procedure with implantation of the DBS system and three months after the onset of active slMFB DBS. These data were then compared to an age- and gender-matched sample of healthy control subjects (HC) (n = 12). Based on reports of subjectively improved social functioning after slMFB DBS [26] and the neuronal overlap of regions stimulated by slMFB DBS and associated with social skills, we hypothesized that DBS normalizes impaired social skills in patients with TRD.

Materials, subjects and methods

Sample description and recruitment

Patients were recruited through the outpatient clinic of the Division of Interventional Biological Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Medical Center, University of Freiburg. Inclusion criteria were a primary diagnosis of major depressive disorder, a current chronic episode ( > two years) or at least four previous episodes of depression, a minimum score of 21 of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) [56] and a score of less than 45 in the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) [57]. All patients included were diagnosed with unipolar depression. Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) was defined as a lacking or inadequate response to all these treatments: (1) three different classes of antidepressants, (2) augmentation/combination therapy of primary antidepressants with other agents, (3) electroconvulsive therapy ( > 6 session) and (4) individual psychotherapy ( > 20 h). Adequacy of previous treatments was assessed with the Antidepressive Treatment History Form (ATHF) [58]. Furthermore, patients with a diagnosis of non-affective psychotic disorder, neurological disorder or medical illness affecting brain function, current or unstably remitted substance abuse, severe personality disorder and acute suicidal ideation were excluded (for a detailed descripition of inclusion and exclusion criteria see clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03653858) or previous publications, e.g. [11]). Data of 12 patients with TRD were analyzed and compared to 12 age- and gender-matched HC. The baseline data before DBS surgery (n = 21) have previously been published [26] and the patients reported in this study represent a subsample (n = 15) of participants who underwent surgery. Of this subsample, three patients did not take part in the follow-up measurement, resulting in a final sample of 12 patients. Healthy control subjects completed an online questionnaire and were eligible if they had no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders, no previous or current psychiatric or psychotherapeutic treatment and no current alcohol or drug abuse, as well as no current depressive symptoms (BDI < 10). All participants were fluent in German.

Procedure

Patients with TRD were tested two to four weeks before stereotactic surgery was performed (see Fig. 1). Stereotactic surgery contains the bilateral implantation of DBS electrodes in the selected brain target (slMFB) under local anesthesia as well as the implantation of the pulse generator in the region of the clavicular under general anesthesia (for a detailed description of the surgery procedure see [59]). The slMFB has been proposed as DBS target in depression considering its central location, interconnections with other DBS targets in depression (e.g. ventral striatum), and its association with reward and motivation seeking behavior [9, 10].

Follow-up data of patients with TRD were analyzed three months after the stimulation onset of slMFB DBS (active DBS). Patients were asked not to change pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy during the study trial. The assessment in the healthy subject sample was repeated three to four months after the first measurement (without intervention). This study was registered at the ‘Deutsches Register Klinischer Studien (DRKS)‘ (identifier DRKS00019092). Patients were recruited from the ongoing FORESEE III trial (clinicaltrials.gov with identifier: NCT03653858). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation (affirmative vote of the University of Freiburgs’s Ethics Committee on 12/21/2017) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Written informed consents were signed by all participants before study participation.

Measures

Clinical symptoms

Severity of symptoms of depression was assessed using self-report (Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hautzinger et al. [60]) as well as expert-rating instruments (Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Montgomery & Åsberg [61]; Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), Hamilton [56]). These scales have reached the status of a gold standard for the evaluation of symptoms of depression according to the diagnostic criteria [62].

Social skills

The EmpaToM [24] is a video-based naturalistic test paradigm. In total, 48 short videos ( ~ 15 s) are presented that display people talking about a situation with either neutral or emotional (negative) valence (24 videos per condition) (for exemplary video stories see [24]). While neutral videos represent the control condition, videos with emotionally negative content represent the experimental condition. To measure affective empathy, participants are asked to rate their own current feelings (‚How do you feel?‘) on a dimensional scale ranging from ‚negative‘ (-2) to ‚positive‘ (2) after each video. The affective responsiveness is calculated as a difference score of empathic responses to emotional and neutral videos describing the ability to affectively resonate with others in response to different situations. For compassion, another question (‚How much compassion do you feel?‘) has to be answered on a dimensional scale ranging from ‚none‘ (0) to ‚very much‘ (6). Theory of mind is assessed by a multiple choice question referring to the thoughts of the person in the video (e.g. ‚Anna thinks that…‘). Participants have to select one out of three options and the accuracy (correct answers/total number of videos; min = 0, max = 1) is calculated. To control for attention and concentration abilities, half of the multiple choice questions demand factual reasoning skills (‚It is correct that…‘). The test thus comprises four conditions (12 trials per condition) with two video categories (neutral and emotional) and two task categories (ToM and non-ToM) (1: neutral, non-ToM; 2: emotional, non-ToM; 3: neutral, ToM; 4: emotional, ToM) (for a detailed description see [24]). For the main analyses, we combined the four categories so that only neutral and emotional or ToM and non-ToM were compared. The videos are presented in a different order for each participant and parallelized test versions presenting new videos were utilized for the follow-up assessment. In the current study, time to respond is generally extended by two seconds compared to the original task because a small pilot trial with five psychiatric patients revealed increased response times in comparison to healthy samples.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics are only displayed descriptively as the main study (FORESEE III) is still ongoing. Difference scores from baseline to follow-up were calculated for affective empathy, compassion, and ToM separately for each group (patients with TRD and HC). Difference scores (baseline-follow-up) were then compared between groups via non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests for two independent samples. Additionally, effect sizes “r” were calculated with r < 0.3 representing small, r < 0.5 medium and r > 0.5 strong effects [63]. We conducted non-parametric tests as the assumptions for parametric tests were not given for all variables of interest (tested using Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests for normal distribution and Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances) and considering our sample’s small size. We also ran equivalence tests [64, 65] to examine the practical similarity of affective responsiveness at follow-up between TRD patients and HC. We set the smallest effect size of interest to a large effect, with bounds of d = −0.80 (lower) and d = 0.80 (upper), and conducted a one-sided test procedure via Welch’s tests for two independent samples [66]. To analyze reliability scores, non-parametric correlation analyses of test and re-test data were calculated exclusively in the HC sample (see Supplementary Table S1). Data were analyzed using MATLAB and IBM SPSS Statistics 20. For all statistical comparisons, p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant (two-tailed).

Results

Sample description

As both groups were matched, gender distribution (male = 7, female = 5) and age were comparable (MTRD = 44.08, SDTRD = 8.08; MHC = 45.33, SDHC = 9.26; TRD vs. HC: U = 62, z = −0.58, p = 0.56, r = 0.13) (Table 1). Furthermore, both groups were comparable with regard to a measure linked to verbal intelligence, namely the multiple choice vocabulary test (MCVT) [67] (TRD: M = 112.33, SD = 14.64; HC: M = 114.67, SD = 12.77; TRD vs. HC: U = 62.5, z = −0.55, p = 0.58, r = 0.12). Descriptively, severity of depression assessed with MADRS, HDRS and BDI decreased in the TRD sample after the onset of DBS (MADRS: M = −10.58, SD = 9.92; HDRS: M = −8.92, SD = 8.79; BDI: M = −11.42, SD = 12.06) (Table 1). In terms of social skills, patients with TRD experienced reduced affective responsiveness (U = 26, z = −2.66, p = 0.01, r = 0.59) and generally reduced feelings of compassion (U = 37, z = −2.02, p = 0.04, r = 0.45) but intact ToM (U = 70.5, z = −0.09, p = 0.93, r = 0.02) at baseline compared to HC (see Supplementary Table S2). For more information about EmpaToM test data at baseline, see additional analyses in the supplement (Supplement 1).

Changes of social skills following DBS onset

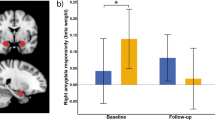

To analyze the effects following three months of active slMFB DBS regarding social skills, the difference scores from baseline to follow-up assessment were compared between TRD patients (n = 12) and HC (n = 12) using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests (Table 2). Significant effects of medium effect size occurred in the affective empathy domain, i.e. with regard to the affective responsiveness to emotional compared to neutral stimuli (TRD: M = 0.10, SD = 0.80; HC: M = −0.44, SD = 0.56; TRD vs. HC: U = 38, z = −1.96, p = 0.05, r = 0.44) (see Fig. 2A). Single comparisons revealed that the affective responsiveness significantly differed between HC and patients with TRD at baseline (U = 26, z = −2.66, p =0.01, r = 0.59) but not at the follow-up assessement (U = 54, z = −1.04, p = 0.30, r = 0.23) indicating a normalized affective responsiveness (see Fig. 2B). This effect was mainly driven by changes from baseline to follow-up in the neutral condition indicating a reduction of the depression-associated negativity bias in patients with TRD (TRD: M = 0.21, SD = 0.40; HC: M = −0.18, SD = 0.32; TRD vs. HC: U = 28, z = −2.54, p = 0.01, r = 0.57) (Supplementary Fig. S1). To determine any equivalence in affective responsiveness at follow-up between the two groups, we conducted equivalence testing. As those results failed to reach statistical significance (T (15,17) = −1.04, p = 0.32), our data provide insufficient evidence to assume similar affective responsiveness at follow-up. Taken together, these findings add to the evidence of specific effects following slMFB DBS in the domain of affective empathy in terms of normalized affective responsiveness. No effects regarding other social skills (compassion, theory of mind) were revealed in the course of slMFB DBS (all p ≥ 0.27; for details see Table 2 and Supplementary Table S3).

Shown are mean scores of differences in affect rating between negative and neutral situations (i.e. affective responsiveness) in patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD, n = 12; in grey) and healthy control subjects (HC, n = 12; in white). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Asteriks indicate a statistically significant difference (p ≤ 0.05, two-sided). Small dots represent individual data points. A Change of affective responsiveness from baseline to follow-up (difference follow-up – baseline) differed significantly between TRD patients in comparison to HC (p = 0.05). B Affective responsiveness scores separately displayed for baseline (left side) and follow-up (right side). At baseline, patients with TRD experienced significantly reduced affective responsiveness compared to HC. At follow-up no difference between the groups was found indicating a normalized affective responsiveness in patients with TRD after three months of active slMFB DBS. n.s. not significant.

Discussion

This study systematically investigated specific social skills (affective empathy, compassion, and theory of mind (ToM)) in patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) before and three months after the onset of deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the supero-lateral medial forebrain bundle (slMFB). Active DBS of the slMFB resulted in a normalized affective responsiveness towards emotionally negative versus neutral stimuli in patients with TRD. None of the other social skills was significantly altered following slMFB DBS. Deficits in compassion remained unchanged and socio-cognitive skills remained intact in the TRD sample.

By behaviorally assessing social skills in the course of slMFB DBS treatment using a naturalistic paradigm, this study contributes to a better understanding of DBS’s effects on social functioning. Three months following the onset of slMFB DBS (follow-up), preoperatively reduced affective responsiveness (baseline) was normalized in patients with TRD. Normalized affective responsiveness following slMFB DBS onset could represent one factor facilitating the social re-integration of these chronically ill patients [17, 20]. The increased negative affect towards neutral stimuli at baseline (e.g. depression-associated negativity bias) was significantly weaker (strong effect size) following slMFB DBS in patients with TRD compared to HC [23, 68]. This finding is in line with a previous study demonstrating a reduced negativity bias six months after the onset of DBS of the subcallosal cingulate gyrus (SCG) in nine patients with TRD [69]. Considering that the SCG and slMFB are part of the same reward-network and that the SCG is anatomically and functionally coupled with regions connected with the medial forebrain bundle [9], our data together with this previous study imply a network-specific effect of DBS in depression. Given the importance to reverse the depression-associated negativity bias for a successful antidepressant treatment [20, 70, 71], this effect might play a significant role in DBS’s antidepressant effects. Furthermore, our results appear to be promising with regard to the social skill deficits hypothesis [72], according to which persisting social skill deficits in patients with depression contribute decisively to both relapsing into depression and to chronic depressive symptoms due to the loss of positive reinforcement during social interactions. Thus, the finding of normalized affective responsiveness in the course of DBS treatment might reduce the probability of a relapse into depression and thereby contribute to a stable, long-term antidepressant effect by enabling positive social interactions. Nevertheless, considering that our equivalence tests revealed a non-significant result of affective responsiveness at follow-up, we cannot conclude that patients with TRD undergoing DBS perform as well as the HC group regarding social skills.

In contrast to affective empathy, we observed no effects following DBS on (preoperatively impaired) compassion in the TRD sample. This finding is unexpected taking into account that the slMFB is directly interconnected with the ventral striatum [41, 42], a region that has been linked to compassion [24, 73]. Although slMFB DBS is known to have rapid antidepressant effects [13, 14], the follow-up period of three months might have been too short to demonstrate effects of DBS altering compassion. Considering that affective empathy represents the basis for compassion [27, 74], feelings of compassion might only improve in the longer-term outcome subsequent to normalized affective responsiveness. Considering the crucial role of compassion in social functioning [75], it could turn out to accelerate these effects by augmenting DBS’s effects on compassion-related brain regions with specific compassion training. To date, there is no study investigating the effects of a social skills training on the antidepressant efficacy of DBS in depression. However, the value of combining DBS treatment with psychotherapy has already been established regarding other mental disorders (e.g. obsessive-compuslive disorder [76]). Therefore, it could prove worthwile to combine DBS therapy in TRD with specific trainings targeting social skill deficits. Supporting the potential of such an approach, compassion training successfully increased feelings of compassion in healthy participants accompanied by increased brain activations in the medial prefrontal cortex [77] and the ventral striatum [73].

While improvements in the domain of affective empathy on the one hand seem to be desirable and important for stable long-term outcomes and successful social functioning after recovery from depression [9, 78], potential side effects of DBS have been discussed critically in another context. Studies investigating DBS of the nucleus subthalamicus treating motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease reported problematic behavioral changes, such as social maladjustment [79, 80] as well as worsening social skills, such as in tasks requiring emotion recognition [81] and ToM [82]. Importantly, the current study demonstrated that after three months of slMFB DBS ToM skills remained intact. This finding is comparable to a previous study in patients with TRD undergoing DBS of the subcallosal cingulate cortex [69]. Furthermore, the current data support evidence that DBS in TRD patients does not negatively alter cognition [83]. Thus, the current study has no indications for ethical concerns of slMFB DBS negatively altering social behavior.

Altogether, the key strengths of the current study are the recruitment of a unique patient sample, and the differentiated assessment of social skills following slMFB DBS by means of a naturalistic paradigm. Alongside these strengths, our study has also limitations. The patient sample of the current study is small due to the experimental status of slMFB DBS for patients with TRD in Germany. The current study thus does not allow to differentiate between DBS treatment responders and non-responders as well as to compare the effects of active and sham stimulation. Future studies are necessary to test the long-term stability of the demonstrated effects with the stimulation turned on and turned off. This is highly relevant given the fact that a discontinuation of stimulation is associated with a relapse of symptoms [16] as well as a reduction of quality of life [84].

In sum, our research demonstrated specific effects following slMFB DBS onset in depression in terms of a normalized affective responsiveness. This effect might facilitate the resumption of social activities after recovery from chronic depression thereby contributing to a stable long-term antidepressant response to DBS. Nevertheless, deficits in compassion persisted. Thus, our data support the idea to combine DBS with specific psychotherapeutic interventions for full recovery.

Data availability

Data are available on reasonable request.

References

Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR* D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–17.

Rathod S, Denee T, Eva J, Kerr C, Jacobsen N, Desai M, et al. Health-related quality of life burden associated with treatment-resistant depression in UK patients: Quantitative results from a mixed-methods non-interventional study. J Affect Disord. 2022;300:551–62.

Jaffe DH, Rive B, Denee TR. The humanistic and economic burden of treatment-resistant depression in Europe: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:247.

Dandekar MP, Fenoy AJ, Carvalho AF, Soares JC, Quevedo J. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: an integrative review of preclinical and clinical findings and translational implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:1094–112.

Kilian HM, Meyer DM, Schlaepfer TE. Putative novel neuromodulatory treatments for affective disorders–What might emerge? Personalized Med Psychiatry. 2019;17:46–50.

Kisely S, Hall K, Siskind D, Frater J, Olson S, Crompton D. Deep brain stimulation for obsessive–compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2014;44:3533–42.

Voineskos D, Daskalakis ZJ, Blumberger DM. Management of treatment-resistant depression: challenges and strategies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:221–34.

Lozano AM, Lipsman N, Bergman H, Brown P, Chabardes S, Chang JW, et al. Deep brain stimulation: current challenges and future directions. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:148–60.

Schlaepfer TE, Bewernick BH, Kayser S, Hurlemann R, Coenen VA. Deep brain stimulation of the human reward system for major depression—rationale, outcomes and outlook. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:1303–14.

Drobisz D, Damborská A. Deep brain stimulation targets for treating depression. Behav Brain Res. 2019;359:266–73.

Coenen VA, Bewernick BH, Kayser S, Kilian H, Boström J, Greschus S, et al. Superolateral medial forebrain bundle deep brain stimulation in major depression: a gateway trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1224–32.

Bewernick BH, Kayser S, Gippert SM, Switala C, Coenen VA, Schlaepfer TE. Deep brain stimulation to the medial forebrain bundle for depression-long-term outcomes and a novel data analysis strategy. Brain Stimul. 2017;10:664–71.

Schlaepfer TE, Bewernick BH, Kayser S, Mädler B, Coenen VA. Rapid effects of deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:1204–12.

Fenoy AJ, Schulz P, Selvaraj S, Burrows C, Spiker D, Cao B, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle: distinctive responses in resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:143–51.

Fenoy AJ, Schulz PE, Selvaraj S, Burrows CL, Zunta-Soares G, Durkin K, et al. A longitudinal study on deep brain stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle for treatment-resistant depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:1–11.

Kilian HM, Bewernick BH, Klein M, Meyer DM, Spanier S, Reinacher PC, et al. Deep Brain Stimulation for Major Depression and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder—Discontinuation of Ongoing Stimulation. Psych. 2020;2:174–85.

Hirschfeld R, Montgomery SA, Keller MB, Kasper S, Schatzberg AF, Möller H-J, et al. Social functioning in depression: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:268–75.

Schiller B, Tönsing D, Kleinert T, Böhm R, Heinrichs M. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic nationwide lockdown on mental health, environmental concern, and prejudice against other social groups. Environ Behav. 2021;54:516–37.

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB. Social Relationships and Mortality. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2012;6:41–53.

Kupferberg A, Bicks L, Hasler G. Social functioning in major depressive disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;69:313–32.

Kisely S, Li A, Warren N, Siskind D. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of deep brain stimulation for depression. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35:468–80.

Bewernick B, Kilian HM, Schmidt K, Reinfeldt RE, Kayser S, Coenen VA, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the supero-lateral branch of the medial forebrain bundle does not lead to changes in personality in patients suffering from severe depression. Psychol Med. 2018;48:2684–92.

Weightman MJ, Air TM, Baune BT. A review of the role of social cognition in major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:179.

Kanske P, Böckler A, Trautwein F-M, Singer T. Dissecting the social brain: Introducing the EmpaToM to reveal distinct neural networks and brain–behavior relations for empathy and Theory of Mind. Neuroimage. 2015;122:6–19.

Guhn A, Merkel L, Hübner L, Dziobek I, Sterzer P, Köhler S. Understanding versus feeling the emotions of others: how persistent and recurrent depression affect empathy. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;130:120–7.

Kilian HM, Schiller B, Schläpfer TE, Heinrichs M. Impaired socio-affective, but intact socio-cognitive skills in patients with treatment-resistant, recurrent depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;153:206–12.

Singer T, Klimecki OM. Empathy and compassion. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R875–8.

Schreiter S, Pijnenborg GH, Aan Het Rot M. Empathy in adults with clinical or subclinical depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:1–16.

Domes G, Spenthof I, Radtke M, Isaksson A, Normann C, Heinrichs M. Autistic traits and empathy in chronic vs. episodic depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;195:144–7.

Banzhaf C, Hoffmann F, Kanske P, Fan Y, Walter H, Spengler S, et al. Interacting and dissociable effects of alexithymia and depression on empathy. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:631–8.

Premack D, Woodruff G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav Brain Sci. 1978;1:515–26.

Bora E, Berk M. Theory of mind in major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:49–55.

Nestor BA, Sutherland S, Garber J. Theory of mind performance in depression: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022;303:233–44.

Inoue Y, Yamada K, Kanba S. Deficit in theory of mind is a risk for relapse of major depression. J Affect Disord. 2006;95:125–7.

Yamada K, Inoue Y, Kanba S. Theory of mind ability predicts prognosis of outpatients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230:604–8.

Segrin C. Social skills deficits associated with depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:379–403.

McCullough JP. Treatment for chronic depression: Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP). J Clin Psychol. 2003;59:833–46.

Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsville BJ, Chevron ES. Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression (Basic Books, New York, 1984).

Weightman MJ, Knight MJ, Baune BT. A systematic review of the impact of social cognitive deficits on psychosocial functioning in major depressive disorder and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Psychiatry Res. 2019;274:195–212.

Renner F, Cuijpers P, Huibers MJH. The effect of psychotherapy for depression on improvements in social functioning: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2014;44:2913–26.

Coenen VA, Schlaepfer TE, Maedler B, Panksepp J. Cross-species affective functions of the medial forebrain bundle—Implications for the treatment of affective pain and depression in humans. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1971–81.

Coenen VA, Panksepp J, Hurwitz TA, Urbach H, Mädler B. Human medial forebrain bundle (MFB) and anterior thalamic radiation (ATR): imaging of two major subcortical pathways and the dynamic balance of opposite affects in understanding depression. J neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24:223–36.

Döbrössy MD, Ramanathan C, Ashouri Vajari D, Tong Y, Schlaepfer T, Coenen VA. Neuromodulation in Psychiatric disorders: Experimental and Clinical evidence for reward and motivation network Deep Brain Stimulation: Focus on the medial forebrain bundle. Eur J Neurosci. 2021;53:89–113.

Schurz M, Radua J, Tholen MG, Maliske L, Margulies DS, Mars RB, et al. Toward a hierarchical model of social cognition: A neuroimaging meta-analysis and integrative review of empathy and theory of mind. Psychol. Bull. 2021;147:293–327.

Kim J-W, Kim S-E, Kim J-J, Jeong B, Park C-H, Son AR, et al. Compassionate attitude towards others’ suffering activates the mesolimbic neural system. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2073–81.

Klimecki OM, Leiberg S, Lamm C, Singer T. Functional neural plasticity and associated changes in positive affect after compassion training. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:1552–61.

Schurz M, Radua J, Aichhorn M, Richlan F, Perner J. Fractionating theory of mind: a meta-analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;42:9–34.

Molenberghs P, Johnson H, Henry JD, Mattingley JB. Understanding the minds of others: A neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;65:276–91.

van Overwalle F. Social cognition and the brain: a meta‐analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:829–58.

Baumgartner T, Schiller B, Hill C, Knoch D. Impartiality in humans is predicted by brain structure of dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. Neuroimage. 2013;81:317–24.

Baumgartner T, Schiller B, Rieskamp J, Gianotti LRR, Knoch D. Diminishing parochialism in intergroup conflict by disrupting the right temporo-parietal junction. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9:653–60.

Schiller B, Gianotti LRR, Baumgartner T, Knoch D. Theta resting EEG in the right TPJ is associated with individual differences in implicit intergroup bias. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2019;14:281–9.

Kämpf MS, Kanske P, Kleiman A, Haberkamp A, Glombiewski J, Exner C. Empathy, compassion, and theory of mind in obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Psychol Psychother. 2022;95:1–17.

Reiter AMF, Kanske P, Eppinger B, Li S-C. The aging of the social mind-differential effects on components of social understanding. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11046.

Winter K, Spengler S, Bermpohl F, Singer T, Kanske P. Social cognition in aggressive offenders: Impaired empathy, but intact theory of mind. Sci Rep. 2017;7:670.

Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–96.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM III - R). Washington DC: APA Press; 1987.

Sackeim HA, Aaronson ST, Bunker MT, Conway CR, Demitrack MA, George MS, et al. The assessment of resistance to antidepressant treatment: Rationale for the Antidepressant Treatment History Form: Short Form (ATHF-SF). J Psychiatr Res. 2019;113:125–36.

Coenen VA, Sajonz B, Reisert M, Bostroem J, Bewernick B, Urbach H, et al. Tractography-assisted deep brain stimulation of the superolateral branch of the medial forebrain bundle (slMFB DBS) in major depression. NeuroImage: Clin. 2018;20:580–93.

Hautzinger M, Keller F, Kühner C BDI-II. Beck-Depressions-Inventar Revision-Manual (Harcourt Test Services, Frankfurt am Main, 2006).

Montgomery S, Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9.

Venn HR, Watson S, Gallagher P, Young AH. Facial expression perception: an objective outcome measure for treatment studies in mood disorders? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9:229–45.

Field A Discovering statistics using SPSS: Third edition (SAGE Publications, London, 2009).

Rogers JL, Howard KI, Vessey JT. Using significance tests to evaluate equivalence between two experimental groups. Psychol Bull. 1993;113:553–65.

Goertzen JR, Cribbie RA. Detecting a lack of association: An equivalence testing approach. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2010;63:527–37.

Lakens D, Scheel AM, Isager PM. Equivalence testing for psychological research: A tutorial. Adv Methods Pract Psychol. Sci. 2018;1:259–69.

Lehrl S, Triebig G, Fischer B. Multiple choice vocabulary test MWT as a valid and short test to estimate premorbid intelligence. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 1995;91:335–45.

Bourke C, Douglas K, Porter R. Processing of facial emotion expression in major depression: a review. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2010;44:681–96.

Merkl A, Neumann W-J, Huebl J, Aust S, Horn A, Krauss JK, et al. Modulation of beta-band activity in the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex during emotional empathy in treatment-resistant depression. Cereb Cortex. 2016;26:2626–38.

Harmer CJ, O’Sullivan U, Favaron E, Massey-Chase R, Ayres R, Reinecke A, et al. Effect of acute antidepressant administration on negative affective bias in depressed patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1178–84.

Rottenberg J, Hindash AC. Emerging evidence for emotion context insensitivity in depression. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;4:1–5.

Libet JM, Lewinsohn PM. Concept of social skill with special reference to the behavior of depressed persons. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1973;40:304–12.

Klimecki OM, Leiberg S, Ricard M, Singer T. Differential pattern of functional brain plasticity after compassion and empathy training. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9:873–9.

Vignemont F, de, Singer T. The empathic brain: how, when and why? Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10:435–41.

Vrticka P, Favre P, Singer T. Compassion and the brain. In: Gilbert P, editor. Compassion: Concepts, Research and Applications. New York: Routledge2017, p. 135-50.

Mantione M, Nieman DH, Figee M, Denys D. Cognitive–behavioural therapy augments the effects of deep brain stimulation in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychol Med. 2014;44:3515–22.

Ashar YK, Andrews-Hanna JR, Halifax J, Dimidjian S, Wager TD. Effects of compassion training on brain responses to suffering others. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2021;16:1036–47.

Synofzik M, Schlaepfer TE. Stimulating personality: ethical criteria for deep brain stimulation in psychiatric patients and for enhancement purposes. Biotechnol J: Healthc Nutr Technol. 2008;3:1511–20.

Schüpbach M, Gargiulo M, Welter M, Mallet L, Béhar C, Houeto J-L, et al. Neurosurgery in Parkinson disease: a distressed mind in a repaired body? Neurology. 2006;66:1811–6.

Houeto J-L, Mallet L, Mesnage V, Du Montcel ST, Béhar C, Gargiulo M, et al. Subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson disease: behavior and social adaptation. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1090–5.

Wagenbreth C, Kuehne M, Heinze H-J, Zaehle T. Deep Brain Stimulation of the Subthalamic Nucleus Influences Facial Emotion Recognition in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease: A Review. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2638.

Péron J, Biseul I, Leray E, Vicente S, Le Jeune F, Drapier S, et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation affects fear and sadness recognition in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2010;24:1–8.

Bergfeld IO, Mantione M, Hoogendoorn MLC, Ruhé HG, Horst F, Notten P, et al. Impact of deep brain stimulation of the ventral anterior limb of the internal capsule on cognition in depression. Psychol Med. 2017;47:1647–58.

Bergfeld, Ooms IO, Lok P, Rue A, de L, Vissers, et al. Efficacy and quality of life after 6–9 years of deep brain stimulation for depression. Brain Stimul. 2022;15:957–64.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Coenen, who conducted the stereotactical neurosurgeries to implant the DBS system as well as Susanne Spanier for the medical attendance of the patients through the whole study and the patients themselves for participating in this study, for their motivation and trust. We also thank Sharon Blanchard-Wacker for proof-reading the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HMK, BS, MH and TES designed and conceptualized the study. HMK and DMMD investigated the patients and collected the data. HMK and BS performed the formal analysis and wrote the paper. MH and TES supervised the study. All authors were critically involved in discussion of the results and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/ personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: The FORESEE III study (see clinicaltrials.gov with identifier: NCT03653858) is an investigator-initiated study funded by Boston Scientific. The funders had no influence on design and conduct of the current study, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, nor on the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kilian, H.M., Schiller, B., Meyer-Doll, D.M. et al. Normalized affective responsiveness following deep brain stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle in depression. Transl Psychiatry 14, 6 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02712-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02712-y