Abstract

Dysregulation of cortical excitation/inhibition (E/I) has been proposed as a neuropathological mechanism underlying core symptoms of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Determining whether dysregulated E/I could contribute to the emergence of behavioural symptoms of ASD requires evidence from human infants prior to diagnosis. In this prospective longitudinal study, we examine differences in neural responses to auditory repetition in infants later diagnosed with ASD. Eight-month-old infants with (high-risk: n = 116) and without (low-risk: n = 27) an older sibling with ASD were tested in a non-linguistic auditory oddball paradigm. Relative to high-risk infants with typical development (n = 44), infants with later ASD (n = 14) showed reduced repetition suppression of 40–60 Hz evoked gamma and significantly greater 10–20 Hz inter-trial coherence (ITC) for repeated tones. Reduced repetition suppression of cortical gamma and increased phase-locking to repeated tones are consistent with cortical hyper-reactivity, which could in turn reflect disturbed E/I balance. Across the whole high-risk sample, a combined index of cortical reactivity (cortical gamma amplitude and ITC) was dimensionally associated with reduced growth in language skills between 8 months and 3 years, as well as elevated levels of parent-rated social communication symptoms at 3 years. Our data show that cortical ‘hyper-reactivity’ may precede the onset of behavioural traits of ASD in development, potentially affecting experience-dependent specialisation of the developing brain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is defined by difficulties in social communication, as well as the presence of restricted interests, repetitive behaviours, and sensory anomalies1. Symptoms emerge in the first years of life, and can be reliably identified through behavioural assessments from toddlerhood. Several recent theories have implicated dysregulated coordination of excitatory and inhibitory signals (E/I) in cortical processing and associated homoeostatic/autoregulatory feedback loops as one potential common mechanism through which multiple background genetic and environmental risk factors could converge to produce behavioural symptoms of autism2,3,4,5,6,7. The high co-occurrence of epilepsy in individuals with ASD (22%) forms one line of evidence for this hypothesis8, in addition to the high rates of ASD in genetic disorders that disturb GABA-ergic functioning (the primary source of inhibitory signalling in the brain), including Fragile X, 15q11-13 and Neurofibromatosis Type 19,10,11. Alterations in GABA and glutamate levels have been identified in adults and children with ASD using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS)12,13,14, although findings are inconsistent across studies and are limited by differences in the measurement variables selected and the lack of spatial precision inherent to this measurement technique. In animal models of ASD, emerging evidence from stem cell studies have implicated an over-production of GABA-ergic neurons15, while several animal models provide support for both GABA and glutamatergic dysfunction in ASD-related phenotypes7,16,17,18. Multiple genetic and environmental risk factors for ASD may converge to disrupt the coordination between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters in the developing brain.

Although there is a reasonable body of evidence linking dysregulated E/I to ASD, establishing a causal relationship to symptoms requires mapping these disruptions before symptoms emerge. Genetic evidence indicates that risk factors for alterations in E/I balance are expressed prenatally, including mutations in genes involved in synaptic development and function6,7,19. Full implications for early brain development remain unclear, particularly since excitatory and/or inhibitory signalling is dynamically shaped over development20,21. For example, GABA-ergic signals are initially excitatory before shifting to their mature inhibitory function sometime in late prenatal/early postnatal development22. Considerable homoeostatic pressure coordinates developmental changes in E/I coordination23,24, and activity-dependent GABA signalling is thought to be critical in optimising the balance between excitation and inhibition in the developing cortex25, with a critical role in shaping cortical sensitive periods. The importance of the interplay between E/I signalling is further supported by the finding that the Nrg1 and ErbB4 excitatory signalling pathways control development of inhibitory circuitry in the mammal cerebral cortex by regulating connectivity of GABA-ergic neurons26. Dysregulation within this pathway has been associated with altered plasticity and the emergence of neurodevelopmental disorders such as schizophrenia and ASD27,28. Early alterations in E/I coordination will be influenced by substantial homoeostatic, autoregulatory or adaptive processes that may further compound initial perturbations and alter phenotypic expression over developmental time3,5,29. Understanding the nature of these changes in ASD will require direct evidence of the presence and consequences of altered E/I balance in human infants prior to symptom onset. The first year of life may be a critical window of interest, since evidence from analysis of SCN2A mutations indicates that over-excitation specific to the first year can result in later autism30,31,32. Considering the availability of pharmacological manipulations that may act on E/I function16, studying this system before the age of 1 year also holds promise for effective delivery of pre-emptive interventions16,33. To do this, researchers need putative indices of the effects of dysregulated E/I signalling on cortical processing that can be measured in human infants.

One such candidate is electrical activity of the cortex measured during a stimulus repetition paradigm. Repetition of a stimulus typically produces a dampening in subsequent neural responses to that stimulus—a phenomenon termed ‘repetition suppression’ that has been linked to neurotransmitter systems important in inhibitory control34,35,36. For example, blocking GABA activity in the inferior colliculus causes more neurons to respond to repeated stimuli37; and activation of GABAergic receptors in the medial geniculate body decreases responses to common stimuli38. Further, models of Fragile X have revealed network hyper-excitability in response to repeated auditory stimulation, including decreased glutamatergic drive on GABAergic inhibitory neurons in sensory cortex10,39. Thus, examining repetition suppression can provide us with insight into inhibition/excitation balance in the developing brain. In young infants, repetition suppression can be readily measured using EEG40,41 a methodology optimal for use with nonverbal populations33.

Emerging evidence suggests that repetition suppression may be altered in the early development of ASD. Indeed, there is broad evidence of reduced repetition suppression or habituation in the visual, auditory, and tactile domains of individuals with ASD relative to typically developing infants and children36,42,43,44,45. Alterations may be particularly pronounced in the auditory domain (indeed, GABA levels measured through MRS are most consistently atypical in the auditory cortex12,46,47). For example, Orekhova et al. linked reduced auditory gating of early-stage event-related potential (ERP) (P50) responses48 to higher ongoing gamma power in 8–12-year-olds with ASD49. Others reported atypical gamma activity during auditory processing in children with ASD and first-degree relatives50,51 as well as atypical theta oscillations in response to speech in adolescents and adults with ASD52. Alterations in auditory repetition suppression have also been reported in adolescents and adults with Fragile X, a genetic condition where 50% of individuals also meet the criteria for ASD and in which there is robust evidence of increased excitatory activity53. Specifically, the researchers found elevated baseline (pre-stimulus) gamma power in response to a tone repetition paradigm, which was associated with reduced habituation of ERPs. Further, there was a concomitant elevation of phase-locking in alpha/beta EEG activity to repeated tones, which was interpreted as a further indication of over-responsiveness in cortical networks. Preliminary evidence also indicates altered EEG responses to auditory or multimodal stimuli in infants at familial risk for autism40,43,44,54, including an initial report of decreased habituation of responses to auditory tones55. Taken together, examining neural indices of repetition suppression in the infant brain may provide an index of cortical hyper-reactivity that is sensitive to early alterations in E/I coordination.

The present study

In the present study, we examined neural responses to repeated auditory tones in an oddball paradigm conducted with 8-month-old infants at low (n = 27) and high (n = 116) familial risk for ASD, an age prior to diagnosis. Additionally, stimulus-locked gamma-band activity may become easier to detect in typical development within the first year of life56,57. Infants at high familial risk for ASD have a 20% chance of developing ASD themselves58, and thus longitudinal studies of this population allow examination of causal paths to the disorder. Previously reported ERP data from studies of auditory processing (including a small subset of infants also included in the present investigation) showed no dampening of response following repetition in infants at high risk55, although no ASD outcome was available at the time. In the present study, we analysed the underlying spectrogram by breaking down the signal into different frequency bands59, which reveals more specific information about the functional organisation of brain activity within the same study design as classic ERP paradigms. Two features of the EEG signal that were expected to produce a robust change with stimulus repetition in the neurotypical brain were evoked high-frequency gamma and inter-trial phase-coherence in the alpha/beta band60,61. Both indices have been linked to E/I balance in previous work53,54. We focused on evoked/time-locked, and not induced activity, because these signals are easier to separate from some of the non-time-locked artefacts that are common in the analysis of ongoing EEG (such as motion, myogenic artefact or electrical line-noise).

As we were concerned about multiple comparisons and the likelihood that effects may be subtle, we took two a priori analytic decisions. First, because the previous literature did not provide clear guidance for a priori selection, we selected time windows, AOIs and frequency bands based on data from the low-risk infants. Specifically, we identified bands/areas associated with habituation of gamma responses across repeated tones in the low-risk group. We then restricted the analysis of the high-risk group to those bands/areas. This avoids multiple comparisons within the high-risk analysis, but does increase the possibility that there are group differences in other scalp regions that we did not assess. Post-hoc analyses conducted to mitigate this are included in the SM. For the ITC, we analysed activity over the same region of interest but selected the time-window and frequency band based on both previous literature and the aggregated grand average technique. Second, two approaches to group analysis have been traditionally used in the infant sibling literature. One is to compare indices across four ‘outcome’ groups: low risk, high-risk typical development, high-risk atypical development or high-risk ASD. We did not follow this path because we had already used the low-risk group to identify windows of interest (and thus including them in comparisons was unfair). Also, the intermediate HR-Atyp group was excluded from main analysis as (1) it would reduce power and (2) no clear predictions could be made about this group (for analysis including the HR-Atyp group, see SM6). The second strategy is to compare responses between high-risk infants with typical development (HR-TD) and those with ASD (HR-ASD), which is the most faithful design to the case/control approach used in the literature58,62. This approach was used in the present manuscript. It was predicted that there would be reduced or absent repetition suppression response in the gamma band as well as elevated phase-coherence to repeated tones in the ASD group relative to the high-risk typically developing group53,55,63.

To exploit the full dimensional nature of the high-risk design, we then examined whether a cortical reactivity index (CRI) (a composite of gamma habituation and ITC) was associated with dimensional variation in later language skills across the whole cohort (LR, HR-TD, HR-Atyp, HR-ASD45,64). The term ‘reactivity index’ was selected to represent the conceptual nature of these EEG responses. Specifically, when a repeated train of stimuli are encountered, ongoing oscillatory activity in the brain can change in two ways. The power or amplitude of oscillations can increase in response to the stimulus; and/or the phase of the oscillation can align with the timing of the stimulus in a consistent way across trials65. Both these reactions produce larger amplitude event-related brain responses and thus in a conceptual sense reflect reactivity. Thus, reduced gamma habituation and higher ITC would additively work to produce a higher CRI. Given the critical role of E/I coordination in experience-dependent specialisation66,67, it was predicted that alterations in neural responses to auditory tones should be associated with poorer language outcomes, as this is a key skill that develops through experience-dependent tuning to the sounds and patterns of the child’s language environment68,69. Finally, it was expected that higher scores on the index would be positively associated with parent-report measures of ASD-related traits at 3 years70.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 116 high-risk (HR) (64 male; 52 female) and 27 low-risk (LR) (14 male; 13 female) children. ‘High-risk’ infants had an older full sibling with a community clinical diagnosis of ASD (recruited from the British Autism Study of Infant Siblings, BASIS—Phase 2; http://www.basisnetwork.org). Infants in the ‘low-risk’ group had no reported family history of ASD or other developmental or genetic disorders (recruited from a volunteer database at Birkbeck Centre for Brain and Cognitive Development), and had at least one older full sibling. Infants recruited for the study attended four visits, at 8 months and 14 months, with follow-up visits at 2 and 3 years. EEG data for the present study are taken from infants during their 8-month visit (Mean = 9.03m, Standard Deviation = 1.1m) and outcome data from the 3-year visit (Mean = 39.05m, Standard Deviation = 3.47m). The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service London Central Ethical Committee (08/H0718/76) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964). Further details of inclusion/exclusion criteria and proband diagnostic phenotyping are provided in SM1: Clinical Assessment.

Within the high-risk group, developmental outcome at 3 years was used as a grouping variable (See Supplementary Materials SM1 for details of assessment). Sixty-four infants were considered typically developing and constituted the HR-TD group. Seventeen infant siblings met gold-standard criteria for ASD (determined by consensus clinical judgement of a group of expert clinical researchers based on information including the ADOS-2, ADI-R and interaction with the child; see SM1, ST2). Lastly, 32 infant siblings were classified as atypically developing, i.e. displayed some developmental concerns but not meeting criteria for an ASD diagnosis (HR-Atyp). Following data cleaning procedures, 131 participants provided sufficient EEG data for analysis (N = 94/113; LR: 14/27; HR-TD = 45/64; HR-Atyp = 21/32; HR-ASD = 14/17; see Table ST1). Sensitivity analysis71 of the total sample size with a power of 1−β = .80 revealed a population effect size of d = .21.

Stimuli

Sounds were presented in an oddball paradigm originally designed by Guiraud et al.55,72. Duration of the sound was 100 ms, with 5 ms rise and fall time. The inter-trial interval was 700 ms. A ‘Standard’ pure tone at 500 Hz was presented with a 77% probability. The paradigm also included two deviant or infrequent tones, which were presented with a 11.5% probability each. One infrequent sound was a white noise deviant, while the other was a pure tone of 650 Hz (pitch deviant). The sound intensity was 70 dB SPL. The sounds were presented for 5–7 min or until the infant became too restless, which on average yielded 477 trials for low-risk and 462 trials for high-risk infants (See Table ST1 for trial breakdown). Following Guiraud et al.55 and a priori hypotheses, responses to the first, second, and third presentation of a Standard tone were examined.

Procedure

The auditory oddball task was administered at the end of a battery of visual EEG tasks. Infants were seated on the parent’s lap facing the experimenter, who blew soap bubbles throughout the recording session to keep the infant calm and engaged. The experiment was conducted in a sound attenuated room, where the sounds were presented from two speakers, 1 m apart, and located 1 m in front of the infant. The Mullen Scales of Early Learning73 were administered in the standardised format; with assessments completed in the same laboratory setting by a small team of experimenters. Parents were also asked to complete a set of questionnaires at home at each visit, including the Social Responsiveness Scale70 at 3 years of age.

EEG recording and pre-processing

Electrophysiological activity was measured using an EGI 128-electrode Hydrocel Sensor Net with the vertex electrode as reference and sampled at 500 Hz. A 0.1–100 Hz band-pass filter was applied offline. The recording was segmented into 1000 ms sections (500 ms pre- and 500 ms post-stimulus presentation). Bad channels in each segment were marked by automatic artefact detection and visual inspection in NetStation (v. 4.5.6). The segments with pronounced artefacts, i.e. gross motor movement, eye blinks, or more than 25 bad channels, were rejected from analysis (104 clean data sets remained). All epochs exceeding 150 μV at any electrode were excluded. At least 30% of trials had to be retained in each category to qualify the dataset to be included in the group analysis. For the remaining trials, channels with a noisy signal were interpolated from neighbouring channels with a clean signal using spline interpolation. Following Guiraud et al.55 and Seery et al.45, all standards that followed either deviant were categorised by position—i.e. Standard 1, Standard 2, and Standard 3, to which the present analysis is confined. There was only one restriction during stimulus presentation—that the deviant sound had to follow at least two standard tones. Due to this, there were notably fewer instances of S3 than S1 and S2. The final number of remaining, artefact free, trials did not significantly differ by group (all ps > .05, see ST1).

Wavelet transform

Four regions of interest (ROIs) in the left and right frontal and tempo-parietal cortex were chosen based on previous investigations into auditory gamma activity24,25 (S1). One hundred and four pre-processed data sets were exported into MatLab® using the free toolbox EEGLAB (v.13.6.5b, http://sccn.ucsd.edu/eeglab/) and re-referenced to the average reference. For analysis of evoked gamma, epochs of raw EEG data were averaged together. A custom-made collection of scripts, WTools (available upon request from Dr Eugenio Parise (available from Dr Parise via email: eugenioparise@tiscali.it)), was used to compute complex Morlet wavelets at 1 Hz intervals between 1 and 80 Hz. A continuous transformation was applied to all epochs through convolution with a wavelet at each frequency in the chosen range, taking the absolute value as a result (i.e. amplitude not power75). To reduce distortion created by convolution, padding of 100 ms at the start and end of the segment was applied to the individual data sets. A baseline period was set between −200 and 0 ms and subtracted from the post-stimulus responses to remove any residual 50 Hz (electrical) noise in the data and to control for pre-stimulus preparatory activity. Amplitude was extracted for low (20–40 Hz) and high (40–60 Hz) gamma bands (30–150 ms post-stimulus onset). The low and high bands were derived from previous examinations of gamma-band activity in infants57. Such evoked (rather than induced or baseline) gamma reflects responses time-locked to the stimulus, reducing the likelihood of contamination by muscle artefact or electrical noise.

Secondly, ITC measures were calculated (collapsed across all standards to improve signal-to-noise ratio). This measure represents whether the distribution of phase angles in a single time-frequency point is uniform, with 1 = perfect phase consistency across trials and 0 = c completely random phase angles60,76,77. When extracting ITC, small trial numbers can artificially skew results76. To identify whether a phase-locking response occurred, we collapsed across all standards for this analysis, such that there were at least 100 good trials included per infant. Individual number of trials per data set were entered as covariates in the model, which also reduced the possibility of introducing further biases from selecting a fixed subset of trials. The number of trials did not affect the stability of the oscillatory response, where the common cut-off for the number of trials used ranges from one78 to between 200 and 80079,80, with many studies not reporting these values81,82. Average ITC was extracted using EEGLAB functions in the 10–20 Hz band, with this frequency band and time-window selected based on the aggregated grand average, previous work with individuals with Fragile X53 and the onset timing of the P150 infant ERP component, which has been shown to be sensitive to reduced habituation in a subset of the high-risk infants (100 to 180 ms; Figure S2)55. However, because ITC is also commonly measured in the theta range in previous studies of auditory processing in infancy, analysis of ITC in the 3–6 Hz is also included in the SM (SM5.2. ITC analysis 3–6 Hz).

Analysis of the P150 component response has been conducted and visualised separately in the SM40,45,55 (details in Figure S2, Supplementary Materials). ERPs are not discussed in the main text beyond this point given that they represent an unspecified combination of power and phase changes in oscillatory rhythms. On the other hand, time-frequency analysis directly relates to the hypothesis under investigation and provides greater sensitivity revealing differences in auditory perception in the developing brain83.

Analysis strategy

The analysis approach was designed to constrain the number of contrasts made in testing effects of developmental outcome, in order to minimise Type 1 error and maximise power in this relatively modest sample. Accordingly, gamma responses to tone repetition were first analysed within the low-risk group to select the topography and frequency band associated with a normative repetition suppression (RS) response. RS was defined as a reduction in gamma amplitude between the first and third standards, given that oscillatory response asymptotes after a second repetition84. We then focused on that region and frequency band, contrasting responses between the HR-TD and HR-ASD groups85,86. Greenhouse−Geisser corrections were applied where appropriate. Similarly, we investigated phase-locking by comparing ITC over the scalp region used in the analysis for HR-ASD and HR-TD groups. The HR-Atyp group were excluded from these analyses for greatest comparability with work with older children using case/control designs85,86; and again to maximise power given the relatively modest sample. However, their data are presented in SM6 (in addition to broadly consistent analyses presented using the alternative approach of pooling the high-risk infants with typical and atypical development into ‘HR-noASD’ groups).

Repetition suppression of evoked gamma and low-frequency ITC were then used to create a ‘Cortical Reactivity Index’ by z-scoring each measure across the cohort (lower repetition suppression of gamma between first and third Standard and greater ITC would give a higher index score), and then averaging the values. We then examined effects of group and continuous relations with dimensional outcomes across the whole cohort. These included development in language skills (difference scores of Expressive and Receptive Language subscales, calculated by subtracting 8-mo from 36-mo scores)73, ADOS severity scores87 at 36 months, as well as the t-score total on the Social Responsiveness Scale™ (SRS™57) at 36 months.

Results

Repetition suppression analysis

Low risk (20–40 Hz, 40–60 Hz)

A paired-samples t test was carried out to examine reductions in amplitude of evoked gamma between the first and third repetition of each standard (1st vs. 3rd Standard) over left and right tempo-parietal regions in the two frequency bands respectively. This indicated a significant decrease in high (40–60 Hz) gamma amplitude (repetition suppression) over the right tempo-parietal region [t(13) = 2.58, p = .023, η2 = .35] but not the left [t(13) = −.65, p = .527, η2 = .034]; with no significant differences in the 20–40 Hz band (ts < 1.6, ps > .54). Corresponding analyses over frontal ROIs revealed no significant effects across either gamma band (ts < 1, ps > .21).

High-risk (40–60 Hz)

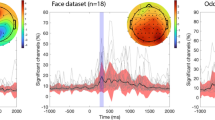

Based on the pattern of findings in LR infants, analysis of ASD outcome was constrained to the 40−60 Hz frequency band over the right tempo-parietal region. A one-way ANOVA revealed an effect of group on Standard 3 – Standard 1 difference scores [F(1,55) = 6.67, p = .012, η2 = .105]; which remained significant after co-varying trial numbers [F(1,55) = 6.53, p = .013, η2 = .105]. Specifically, there was a decrease in gamma activation between the first and third repetition in HR-TD, relative to an increase in the HR-ASD group. Figure 1 illustrates the responses for the three groups; SM3 indicates that responses were not due to ocular muscle activity88 (see SM3). Notably, the main effect of group persisted when the HR-Atyp group was included in the model (see SM5). Our additional post-hoc analyses of evoked theta (3–6 Hz over 50–400 ms) and late evoked gamma (40–60 Hz over 200–350 ms) did not reveal significant differences for high-risk groups (SM5).

a Amplitude difference of 40–60 Hz evoked gamma in the right tempo-parietal electrodes between Standard 3 and Standard 1. b Difference plots of the gamma responses to the repetition of standard tone (Standard3 − Standard1) in 40–60 Hz evoked gamma in right tempo-parietal electrodes. It appears while the LR group shows a clear repetition suppression, the HR-ASD group shows an increase in gamma activation. c 3D Scalp maps of the difference in total 40–60 Hz gamma activation between third and first frequent tone in the 100–150 ms time period in the three groups. d Total inter-trial coherence responses collapsed across all infants and all Standard trials. The 100−180 ms time-window and 10–20 Hz band was chosen as the area of interest for group comparisons. e Inter-trial coherence values for all standards collapsed together in the high-risk infant siblings from right tempo-parietal scalp region. LR group included for reference. Note. Error bars depict standard error of the mean for each group respectively. LR low risk. * Denotes signficance level (i.e. p < .05)

ITC

Within the same ROI (right tempo-parietal region), a univariate ANOVA was used to examine group differences (HR-ASD, HR-TD) in ITC in the alpha-beta band (10–20 Hz). This revealed significantly greater ITC in the HR-ASD than the HR-TD group [F(1,55) = 4.62, p = .036, η2 = .06]; which remained significant when co-varied with the number of trials infants were presented with [F(1,54) = 4.58, p = .037, η2 = .06]. When the HR-Atyp group was included, there were no significant differences in ITC across the three risk groups (see SM6 for further details of this exploratory analysis). Additional post-hoc analysis of ITC within the theta range revealed similar phase-locking values in the same time period, with no significant differences in phase-locking values between the high-risk groups (all ps > .2; SM5.2).

Cortical reactivity index

A composite CRI was created by computing z-scores for the 40–60 Hz evoked gamma and 10–20 Hz ITC responses for the whole high-risk group, and then averaged across the two indices. A higher score on the index would reflect diminished auditory repetition suppression. As expected, an ANOVA indicated significantly higher scores in the HR-ASD than the HR-TD group [F(1,55) = 15.16, p < .001, η2 = .22]. A logistic regression indicated that this index correctly classified 93% of the HR-TD group and 50% of the ASD group [β = 2.74, S.E. = 0.87, w = 9.89, p = .002]. When the whole sample was included, the main effect of group remained significant, and HR-ASD infants maintained significantly higher CRI scores than the other groups (ps between .002 and .045; see SM4).

As shown in Fig. 2, the composite score was also significantly associated with development in Receptive Language between 8 and 36 months across all infants in the sample [r(88) = −0.25, p = .032]; controlling for trial number [r(88) = −0.25, p = .03], and was also associated with SRS™ Total T-scores [r(88) = 0.22, p = .04]; controlling for number of trials [r(88) = 0.22, p = .039], but not with change in Expressive Language [r(85) = −0.17, p = −.20]; controlling for trial number [r(85) = −0.12, p = .27]. No significant association was found between scores on the index and the ADOS severity scores [r(88) = 0.15, p = .162]; controlling for trial number [r(85) = 0.16, p = .135].

a Cortical reactivity index z-scores for all outcome groups. Note that the HR-Atyp group is visualised here but was not included in the HR-TD vs. HR-ASD comparison. Composite score for difference in evoked gamma (40–60 Hz) and ITC responses (10–20 Hz) over right tempo-parietal ROI was associated with b smaller change in Receptive Language scores between 8 and 36 months and c higher SRS™ scores, a dimensional measure of ASD-related traits. LR low risk, HR-TD high-risk—typically developing, HR-Atyp high-risk—atypical development, HR-ASD high risk—autism spectrum disorder. Note: The fit line is for an average of all infants. Error bars depict standard error of the mean

Discussion

Alterations in excitatory and inhibitory signalling are a feature of several leading neurobiological theories of sensory perturbations observed in ASD, with some researchers proposing that behavioural symptomology is the cumulative developmental consequence of altered excitatory and inhibitory coordination within cortical systems2,3,6,7,89. To our knowledge, we present the first human evidence that elevated cortical reactivity is present in infants with later ASD prior to the emergence of behavioural symptoms. This is consistent with the presence of alterations in excitatory and inhibitory function in infancy. In our work, reduced repetition suppression of evoked gamma and generally increased alpha/beta phase-locking to auditory repetition were present in 8-month-old infants with later ASD. A combined index of cortical reactivity was associated with reduced receptive language and social communication at 3 years dimensionally across the entire cohort. Altered EEG responses to repetition may therefore be a candidate stratification biomarker for language functioning in ASD. As atypical cortical auditory reactivity has been previously linked to weakened GABA circuits in mouse infancy67, our results could reflect a lack of regulation within the E/I balance in infants with later ASD.

Enhanced reactivity within the developing cortex may relate to the alterations in connectivity that have been broadly observed in ASD, due to the experience-dependent nature of synapse development43,90,91. Indeed, 14-month-old infants with later ASD and high levels of restricted and repetitive behaviours show significant over-connectivity between frontal and temporal regions90. Increased spontaneous activity in early development could also be associated with structural overgrowth92,93, because internal activity-driven processes contribute to brain growth94. Future work combining both MRI and EEG techniques in young infants will allow us to investigate the bidirectional links between structure and function in the infant brain. Further, longitudinal studies with repeated EEG phenotyping are necessary to determine whether the observed alterations in cortical reactivity represent a developmentally pervasive phenomenon, or a transient developmental delay in the normal increases in inhibitory activity observed in early infancy2,20. Several influential theories propose significant mechanisms that would alter the expression of excitatory/inhibitory processing over developmental time3,7,20.

Cortical reactivity to repetition of sensory stimuli could reflect processes that disrupt the experience-dependent specialisation of the social brain, as the inhibitory signals critical for repetition suppression are also critical in shaping sensitive periods in early development16,66. Altered trajectories of specialisation are an emerging theme from prospective studies of high-risk infants. Across the first year of life infants with later ASD show a decline in interest in eyes and faces62, emergence of slowed attention-shifting95 and early signs of language delays33,86. Such behavioural changes are related to alterations in specialised brain activity. For example, between 5 and 6 months, infants with later ASD show reduced sensitivity over temporal cortex to human sounds96,97 and altered ERP responses to pictures of faces98,99. Intriguingly, our index of cortical reactivity related to dimensional variation in receptive language growth between 8 and 36 months, an age-range associated with specialisation of language regions100. Language acquisition is dependent on attention to novelty and change, and it is likely that poor tuning to repetition would have a detrimental effect on this process. Testing how our index of cortical reactivity relates to more fine-grained indices of language and social communication through a longitudinal investigation will be an important next step.

Elevated cortical reactivity could result from a range of impairments at the molecular level, contributing to reduced inhibition or increased excitation. Select environmental risk factors may have converging effects through oxidative stress, which is thought to impact parvalbumin inhibitory interneurons. This is thought to be a key mechanism for regulation of E/I balance and maintenance of neural microcircuitry16,101, and form a unified risk pathway for schizophrenia and some forms of autism102,103. This is supported by Selten et al., who provide succinct evidence of cascading effects of the inhibitory system dysregulation in the cortex and hippocampus on signal processing and later phenotypic changes associated with psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders6. Recent work with knock-out models of ASD (including mice models of Fragile X) also implicates early increases in spontaneous synchronous activity and upregulation of synaptic turnover in sensory cortices as a common phenotype, consistent with excess cortical reactivity11,104. In human adults with Fragile X syndrome, reduced habituation of neural responses to tones was associated with elevated gamma at baseline53, which in animal models can be rescued with the GABAB-receptor agonist arbaclofen17. We did not examine baseline or resting state gamma that was previously found atypical in high-risk populations43,105 due to the increased likelihood of contamination by muscle artefact, and so pharmacological manipulation studies of the repetition suppression of gamma responses are warranted. Nonetheless, the results provide an index suitable for measuring the effects of novel pharmaceutical treatments on core biochemical pathways implicated in autism.

These results further complement previous findings of altered habituation profiles in ASD. Reduced habituation/repetition suppression of ERP responses have been observed in a subsample of the present cohort of high-risk infants55 and repetition of speech sounds in other samples45. In the visual domain, toddlers with ASD showed delayed adaptation to repetition, particularly to social stimuli99, while adults showed diminished repetition suppression with increasing levels of ASD traits106. Repetition suppression is a critical process by which the brain devotes resources to novel and unexpected stimuli. Atypical/reduced repetition suppression is therefore likely to affect the efficacy with which the brain encodes complex stimuli, such as language, which rely heavily on focusing attention on important dimensions of change in auditory signals64,107. Atypical repetition suppression could also contribute to exaggerated sensory sensitivities observed in children with ASD49, as well as delayed language ability, a strong predictor of developmental outcomes in individuals with ASD108,109.

In summary, findings from the current study indicate that cortical reactivity is present at 8 months of age in infants who later develop ASD. It remains to be established whether these responses are stable in early development, or change dynamically over time. This study provides the first evidence for the emergence of cortical consequences within the right tempo-parietal region from alterations in E/I coordination as early as 8 months of age in infants with later ASD, and offers candidate mechanistic pathways by linking alterations in gamma to individual level differences in later language and social functioning.

References

Association A. P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) 1679p. (American Psychiatric Pub, Arlington, VA, 2013).

Rubenstein, J. L. R. & Merzenich, M. M. Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes. Brain. Behav. 2, 255–267 (2003).

Nelson, S. B. & Valakh, V. Excitatory/inhibitory balance and circuit homeostasis in autism spectrum disorders. Neuron 87, 684–698 (2015).

Rubenstein, J. L. R. Three hypotheses for developmental defects that may underlie some forms of autism spectrum disorder. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 23, 118–123 (2010).

Johnson, M. H., Jones, E. J. H. & Gliga, T. Brain adaptation and alternative developmental trajectories. Dev. Psychopathol. 27, 425–442 (2015).

Selten, M., van Bokhoven, H. & Nadif Kasri, N. Inhibitory control of the excitatory/inhibitory balance in psychiatric disorders. F1000Res. 7, 23 (2018).

Lee, E., Lee, J. & Kim, E. Excitation/inhibition imbalance in animal models of autism spectrum disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 81, 838–847 (2017).

Bolton, P. F. et al. Epilepsy in autism: features and correlates. Br. J. Psychiatry 198, 289–294 (2011).

Coghlan, S. et al. GABA system dysfunction in autism and related disorders: from synapse to symptoms. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 2044–2055 (2012).

d'Hulst, C. et al. Decreased expression of the GABAA receptor in fragile X syndrome. Brain Res. 1121, 238–245 (2006).

Isshiki, M. et al. Enhanced synapse remodelling as a common phenotype in mouse models of autism. Nat. Commun. 5, 4742 (2014).

Gaetz, W. et al. GABA estimation in the brains of children on the autism spectrum: measurement precision and regional cortical variation. Neuroimage 86, 1–9 (2014).

Horder, J. et al. Reduced subcortical glutamate/glutamine in adults with autism spectrum disorders: a [1H]MRS study. Transl. Psychiatry 3, e279 (2013).

Spencer, A. E., Uchida, M., Kenworthy, T., Keary, C. J. & Biederman, J. Glutamatergic dysregulation in pediatric psychiatric disorders: a systematic review of the magnetic resonance spectroscopy literature. J. Clin. Psychiatry 75, 1226–1241 (2014).

Mariani, J. et al. FOXG1-dependent dysregulation of GABA/glutamate neuron differentiation in autism spectrum disorders. Cell 162, 375–390 (2015).

Yizhar, O. et al. Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature 477, 171–178 (2011).

Gandal, M. J. et al. Validating γ oscillations and delayed auditory responses as translational biomarkers of autism. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 1100–1106 (2010).

Casanova, M. F., Buxhoeveden, D. P., Switala, A. E. & Roy, E. Minicolumnar pathology in autism. Neurology 58, 428–432 (2002).

Lionel, A. C. et al. Rare exonic deletions implicate the synaptic organizer Gephyrin (GPHN) in risk for autism, schizophrenia and seizures. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 2055–2066 (2013).

Dorrn, A. L., Yuan, K., Barker, A. J., Schreiner, C. E. & Froemke, R. C. Developmental sensory experience balances cortical excitation and inhibition. Nature 465, 932–936 (2010).

Sun, Y. J. et al. Fine-tuning of prebalanced excitation and inhibition during auditory cortical development. Nature 465, 927–931 (2010).

Balz, J. et al. GABA concentration in superior temporal sulcus predicts gamma power and perception in the sound-induced flash illusion. Neuroimage 125, 724–730 (2016).

Liu, G. Local structural balance and functional interaction of excitatory and inhibitory synapses in hippocampal dendrites. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 373–379 (2004).

Gulyás, A. I., Megı́as, M., Emri, Z. & Freund, T. F. Total number and ratio of excitatory and inhibitory synapses converging onto single interneurons of different types in the CA1 area of the rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 19, 10082–10097 (1999).

Le Magueresse, C. & Monyer, H. GABAergic interneurons shape the functional maturation of the cortex. Neuron 77, 388–405 (2013).

Fazzari, P. et al. Control of cortical GABA circuitry development by Nrg1 and ErbB4 signalling. Nature 464, 1376–1380 (2010).

Hahn, C. G. et al. Altered neuregulin 1–erbB4 signaling contributes to NMDA> receptor hypofunction in schizophrenia. Nat. Med. 12, 824–828 (2006).

Marín, O. Interneuron dysfunction in psychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 107–120 (2012).

Mullins, C., Fishell, G. & Tsien, R. W. Unifying views of autism spectrum disorders: a consideration of autoregulatory feedback loops. Neuron 89, 1131–1156 (2016).

Ben-Shalom, R. et al. Opposing effects on NaV1.2 function underlie differences between SCN2A variants observed in individuals with autism spectrum disorder or infantile seizures. Biol. Psychiatry 82, 224–232 (2017).

Sanders, S. J. et al. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature 485, 237–241 (2012).

Weiss, L. A. et al. Sodium channels SCN1A, SCN2A and SCN3A in familial autism. Mol. Psychiatry 8, 186–194 (2003).

Webb, S. J. et al. Guidelines and best practices for electrophysiological data collection, analysis and reporting in autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 425–443 (2015).

Auksztulewicz, R. & Friston, K. Repetition suppression and its contextual determinants in predictive coding. Cortex 80, 125–140 (2016).

Hsu, Y.-F., Hämäläinen, J. A. & Waszak, F. Repetition suppression comprises both attention-independent and attention-dependent processes. Neuroimage 98, 168–175 (2014).

Nordt, M., Hoehl, S. & Weigelt, S. The use of repetition suppression paradigms in developmental cognitive neuroscience. Cortex 80, 61–75 (2016).

Pérez-González, D., Hernández, O., Covey, E. & Malmierca, M. S. GABAA-mediated inhibition modulates stimulus-specific adaptation in the inferior colliculus. PLoS One 7, e34297 (2012).

Duque, D., Malmierca, M. S. & Caspary, D. M. Modulation of stimulus-specific adaptation by GABAA receptor activation or blockade in the medial geniculate body of the anaesthetized rat. J. Physiol. 592, 729–743 (2014).

Gibson, J. R., Bartley, A. F., Hays, S. A. & Huber, K. M. Imbalance of neocortical excitation and inhibition and altered UP states reflect network hyperexcitability in the mouse model of Fragile X Syndrome. J. Neurophysiol. 100, 2615–2626 (2008).

Snyder, K. A. & Keil, A. Repetition suppression of induced gamma activity predicts enhanced orienting toward a novel stimulus in 6-month-old infants. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 20, 2137–2152 (2008).

Snyder, K. A., Garza, John, Zolot, Liza & Kresse, Anna Electrophysiological signals of familiarity and recency in the infant brain. Infancy 15, 487–516 (2010).

Sinha, P. et al. Autism as a disorder of prediction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 15220–15225 (2014).

Righi, G., Tierney, A. L., Tager-Flusberg, H. & Nelson, C. A. Functional connectivity in the first year of life in infants at risk for autism spectrum disorder: an EEG Study. PLoS One 9, e105176 (2014).

Levin, A. R., Varcin, K. J., O’Leary, H. M., Tager-Flusberg, H. & Nelson, C. A. EEG power at 3 months in infants at high familial risk for autism. J. Neurodev. Disord. 9, 34 (2017).

Seery, A., Tager-Flusberg, H. & Nelson, C. A. Event-related potentials to repeated speech in 9-month-old infants at risk for autism spectrum disorder. J. Neurodev. Disord. [Internet]. 6 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4416338/ (2014).

Rojas, D. C., Singel, D., Steinmetz, S., Hepburn, S. & Brown, M. S. Decreased left perisylvian GABA concentration in children with autism and unaffected siblings. Neuroimage 86, 28–34 (2014).

Rojas, D. C., Becker, K. M. & Wilson, L. B. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of glutamate and GABA in autism: implications for excitation-inhibition imbalance theory. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2, 46–57 (2015).

De Haan, M. Infant EEG and Event-Related Potentials p.345 Psychology Press, New York (2013).

Orekhova, E. V. et al. Sensory gating in young children with autism: relation to age, IQ, and EEG gamma oscillations. Neurosci. Lett. 434, 218–223 (2008).

Rojas, D. C., Maharajh, K., Teale, P. & Rogers, S. J. Reduced neural synchronization of gamma-band MEG oscillations in first-degree relatives of children with autism. BMC Psychiatry 8, 66 (2008).

Rojas, D. C. et al. Transient and steady-state auditory gamma-band responses in first-degree relatives of people with autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism 2, 11 (2011).

Jochaut, D. et al. Atypical coordination of cortical oscillations in response to speech in autism. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 171 (2015).

Ethridge, L. E. et al. Reduced habituation of auditory evoked potentials indicate cortical hyper-excitability in Fragile X Syndrome. Transl. Psychiatry 6, 787 (2016).

Snijders, T. M., Milivojevic, B. & Kemner, C. Atypical excitation–inhibition balance in autism captured by the gamma response to contextual modulation. NeuroImage Clin. 3, 65–72 (2013).

Guiraud, J. A. et al. and BASIS Team. Differential habituation to repeated sounds in infants at high risk for autism. Neuroreport 22, 845–849 (2011).

Csibra, G., Davis, G., Spratling, M. W. & Johnson, M. H. Gamma oscillations and object processing in the infant brain. Science 290, 1582–1585 (2000).

Grossmann, T., Johnson, M. H., Farroni, T. & Csibra, G. Social perception in the infant brain: gamma oscillatory activity in response to eye gaze. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2, 284–291 (2007).

Ozonoff, S. et al. Recurrence risk for autism spectrum disorders: a baby siblings research consortium study. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-2825 (2011).

Varela, F., Lachaux, J. P., Rodriguez, E. & Martinerie, J. The brainweb: phase synchronization and large-scale integration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 229–239 (2001).

Tallon-Baudry, C., Bertrand, O., Delpuech, C. & Pernier, J. Stimulus specificity of phase-locked and nonphase- locked 40 Hz visual responses in human. J. Neurosci. 16, 4240–4249 (1996).

Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 134, 9–21 (2004).

Jones, W. & Klin, A. Attention to eyes is present but in decline in 2-6-month-old infants later diagnosed with autism. Nature 504, 427–431 (2013).

Matsuzaki, J. et al. Progressively increased M50 responses to repeated sounds in autism spectrum disorder with auditory hypersensitivity: a magnetoencephalographic study. PLoS One 9, e102599 (2014).

Edgar, J. C. et al. Neuromagnetic oscillations predict evoked-response latency delays and core language deficits in autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 395–405 (2013).

Makeig, S., Debener, S., Onton, J. & Delorme, A. Mining event-related brain dynamics. Trends Cogn. Sci. 8, 204–210 (2004).

Hensch, T. K. Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 877–888 (2005).

Gogolla, N., Takesian, A. E., Feng, G., Fagiolini, M. & Hensch, T. K. Sensory integration in mouse insular cortex reflects GABA circuit maturation. Neuron 83, 894–905 (2014).

Maurer, D. & Werker, J. F. Perceptual narrowing during infancy: a comparison of language and faces. Dev. Psychobiol. 56, 154–178 (2014).

Kuhl, P. K. et al. Infants show a facilitation effect for native language phonetic perception between 6 and 12 months. Dev. Sci. 9, F13–F21 (2006).

Constantino, J. N. (SRSTM-2) Social Responsiveness ScaleTM, Second Edition | WPS. Retrieved from https://www.wpspublish.com/store/p/2994/srs-2-social-responsiveness-scale-second-edition. (2012).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160 (2009).

Kushnerenko, E. et al. Processing acoustic change and novelty in newborn infants. Eur. J. Neurosci. 26, 265–274 (2007).

Mullen, E. M. Mullen scales of early learning (58-64). (AGS, Circle Pines, MN, 1995).

Kushnerenko, E. et al. Maturation of the auditory event-related potentials during the first year of life. Neuroreport 13, 47–51 (2002).

Kampis D., Parise E., Csibra G., Kovács Á. M. Neural signatures for sustaining object representations attributed to others in preverbal human infants. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. [Internet]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4685805/ (2015).

Cohen, M. X. Analyzing Neural Time Series Data: Theory and Practice (pp. 615. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2014).

Tallon-Baudry, C. & Bertrand, O. Oscillatory gamma activity in humans and its role in object representation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 3, 151–162 (1999).

Milne, E. Increased intra-participant variability in children with autistic spectrum disorders: evidence from single-trial analysis of evoked EEG. Front. Psychol. 2, 30–51 (2011).

Musacchia, G., Ortiz-Mantilla, S., Realpe-Bonilla, T., Roesler, C. P. & Benasich, A. A. Infant auditory processing and event-related brain oscillations. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE 101, (2015).

Nash-Kille, A. & Sharma, A. Inter-trial coherence as a marker of cortical phase synchrony in children sensorineural hearing loss and auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder fitted with hearing aids and cochlear implants. Clin. Neurophysiol. J. Int Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 125, 1459–1470 (2014).

Ortiz-Mantilla, S., Hämäläinen, J. A., Realpe-Bonilla, T. & Benasich, A. A. Oscillatory dynamics underlying perceptual narrowing of native phoneme mapping from 6 to 12 months of age. J. Neurosci. 36, 12095–12105 (2016).

Bosseler, A. et al. Theta brain rhythms index perceptual narrowing in infant speech perception. Front. Psychol. 4, 690 (2013).

Isler, J. R. et al. Toward an electrocortical biomarker of cognition for newborn infants. Dev. Sci. 15, 260–271 (2012).

Gruber, T., Malinowski, P. & Müller, M. M. Modulation of oscillatory brain activity and evoked potentials in a repetition priming task in the human EEG. Eur. J. Neurosci. 19, 1073–1082 (2004).

Ozonoff, S. et al. A prospective study of the emergence of early behavioral signs of autism. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 49, 256–266.e2 (2010).

Mitchell, S. et al. Early language and communication development of infants later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 27, 69–78 (2006).

Gotham, K., Pickles, A. & Lord, C. Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 39, 693–705 (2009).

Kampis, D., Parise, E., Csibra, G. & Kovács, Á. M. On potential ocular artefacts in infant electroencephalogram: a reply to comments by Köster. Proc. R. Soc. B. 283, 20161285 (2016).

Johnson, M. H. Autism as an adaptive common variant pathway for human brain development. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 25, 5–11 (2017).

Orekhova, E. V. et al. EEG hyperconnectivity in high-risk infants is associated with later autism. J. Neurodev. Disord. 6, 40 (2014).

Courchesne, E. & Pierce, K. Brain overgrowth in autism during a critical time in development: implications for frontal pyramidal neuron and interneuron development and connectivity. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 23, 153–170 (2005).

Levitt, P., Eagleson, K. L. & Powell, E. M. Regulation of neocortical interneuron development and the implications for neurodevelopmental disorders. Trends Neurosci. 27, 400–406 (2004).

Redcay, E. & Courchesne, E. When is the brain enlarged in autism? A meta-analysis of all brain size reports. Biol. Psychiatry 58, 1–9 (2005).

Zhou, Z. et al. Brain-specific phosphorylation of MeCP2 regulates activity-dependent Bdnf transcription, dendritic growth, and spine maturation. Neuron 52, 255–269 (2006).

Elsabbagh, M. et al. and BASIS Team. Disengagement of visual attention in infancy is associated with emerging autism in toddlerhood. Biol. Psychiatry 74, 189–194 (2013).

Blasi, A. et al. Atypical processing of voice sounds in infants at risk for autism spectrum disorder. Cortex 71, 122–133 (2015).

Lloyd-Fox, S. et al. Reduced neural sensitivity to social stimuli in infants at risk for autism. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 2012–3026 (2013).

Elsabbagh, M. et al. Infant neural sensitivity to dynamic eye gaze is associated with later emerging autism. Curr. Biol. 22, 338–342 (2012).

Webb, S. J. et al. Developmental change in the ERP responses to familiar faces in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders versus typical development. Child Dev. 82, 1868–1886 (2011).

Dehaene-Lambertz, G. Cerebral specialization for speech and non-speech stimuli in infants. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 12, 449–460 (2000).

Hu, H., Gan, J. & Jonas, P. Interneurons. Fast-spiking, parvalbumin GABAergic interneurons: from cellular design to microcircuit function. Science 345, 1255263 (2014).

Steullet, P. et al. Oxidative stress-driven parvalbumin interneuron impairment as a common mechanism in models of schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 22, 936 (2017).

Richetto, J., Calabrese, F., Riva, M. A. & Meyer, U. Prenatal immune activation induces maturationdependent alterations in the prefrontal GABAergic transcriptome. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 351–361 (2014).

Gonçalves, J. T., Anstey, J. E., Golshani, P. & Portera-Cailliau, C. Circuit level defects in the developing neocortex of Fragile X mice. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 903–909 (2013).

Tierney, A. L., Gabard-Durnam, L., Vogel-Farley, V., Tager-Flusberg, H. & Nelson, C. A. Developmental trajectories of resting EEG power: an endophenotype of autism spectrum disorder. PLoS One 7, e39127 (2012).

Ewbank, M. P. et al. Repetition suppression in ventral visual cortex is diminished as a function of increasing autistic traits. Cereb. Cortex 25, 3381–3393 (2015).

Arimitsu, T. et al. Functional hemispheric specialization in processing phonemic and prosodic auditory changes in neonates. Front. Psychol. 2, 202 (2011).

Szatmari, P., Bryson, S. E., Boyle, M. H., Streiner, D. L. & Duku, E. Predictors of outcome among high functioning children with autism and Asperger syndrome. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 44, 520–528 (2003).

Pickles, A., Anderson, D. K. & Lord, C. Heterogeneity and plasticity in the development of language: a 17- year follow-up of children referred early for possible autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 55, 1354–1362 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the families who gave up their time to contribute to this study. This work was supported by MRC Programme Grant no. G0701484, the BASIS funding consortium led by Autistica, Wellcome ISSF grant (Emily Jones), ESF COST Action BM1004, and the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking under grant agreement no. 115300, resources of which are composed of financial contribution from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007—2013) and EFPIA companies’ in-kind contribution. Anna Kolesnik was funded by an ESRC DTC award (Grant no. ES/J500021/1).

The BASIS Team

The BASIS team consist of: Simon Baron-Cohen, Patrick Bolton, Anna Blasi, Celeste Cheung, Kim Davies, Mayada Elsabbagh, Janice Fernandes, Isobel Gammer, Elena Kushnerenko, Michelle Liew, Sarah Lloyd-Fox, Greg Pasco, Andrew Pickles, Helena Ribeiro, Erica Salomone, Przemek Tomalski, Leslie Tucker.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Members of the BASIS Team are listed below Acknowledgements.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolesnik, A., Begum Ali, J., Gliga, T. et al. Increased cortical reactivity to repeated tones at 8 months in infants with later ASD. Transl Psychiatry 9, 46 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-019-0393-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-019-0393-x

This article is cited by

-

The ‘PSILAUT’ protocol: an experimental medicine study of autistic differences in the function of brain serotonin targets of psilocybin

BMC Psychiatry (2024)

-

Temporal imprecision of phase coherence in schizophrenia and psychosis—dynamic mechanisms and diagnostic marker

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

-

“Neural Noise” in Auditory Responses in Young Autistic and Neurotypical Children

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2024)

-

Neonatal brain dynamic functional connectivity in term and preterm infants and its association with early childhood neurodevelopment

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Exploratory evidence for differences in GABAergic regulation of auditory processing in autism spectrum disorder

Translational Psychiatry (2023)