Abstract

Study design

An online survey.

Objectives

To describe how healthcare providers manage depression after spinal cord damage (SCD) and to identify factors that predict use of recommended depression management practices.

Setting

An international cohort of respondents who provide clinical care to individuals with SCD.

Methods

An online survey was distributed to clinicians caring for individuals with SCD. The 20-question survey inquired about participant demographic and professional information, their knowledge and beliefs about depression after SCD, their methods of treating depression in SCD, and perceived barriers to treatment of depression.

Results

One hundred eleven individuals took this survey. Participants estimated on average that 48.7% of their patients with SCD have depression, and nearly two-thirds (62.2%) reported using their own clinical judgment to identify the condition. Respondents cited barriers to depression treatment including patient denial of depression (47.7%), stigmas attached to depression (41.4%), and lack of availability and high cost of counseling (45.9% and 35.1%, respectively) and antidepressant medications (5.4% and 10.8%, respectively). The belief that one is well trained to handle depressive symptoms predicted increased frequency of screening for depression and implementation of recommended treatments for depression.

Conclusions

Respondents to this survey under-utilize valid screening measures and likely over-estimate the prevalence of depression in SCD. They cited a number of barriers to treatment for depression. Our results underscore the need for improved mental health education among SCD providers and the use of valid depression screening measures to help focus limited mental health services and treatments on those who need them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A 2015 meta-analysis by Williams and Murray found that only 22.2% of individuals with spinal cord damage (SCD) have co-existing depression [1]. Depression is not simply a sign of grief; they appear to be independent and distinct entities [2]. Depression is associated with learned helplessness and reduced disability acceptance as well as poor quality of life and low community participation among individuals with SCD [1]. Hence, depression is considered an abnormal response to SCD that merits treatment.

Depression is less likely to be treated in people with SCD compared to uninjured persons [2]. However, Fann et al. found that substantial majorities of individuals with SCD are willing to try common treatments for depression including individual counseling (77%), antidepressant medications (72%), and structured exercise (78%) [3]. Little is known about why depression in SCD is under-treated, and developing an understanding of the factors that contribute to this disparity may enable clinicians to improve the psychosocial outcomes and social and community participation of individuals with SCD.

The authors designed a survey (Supplementary Appendix 1) and distributed it to an international cohort of SCD professionals. Our main goal was to understand which demographic and professional factors influence one’s beliefs about screening and treatment strategies for depression in SCD. Our hope was that by better understanding barriers and facilitators to the use of evidence-based screening and treatment measures [4], we could identify ways to improve the identification and treatment of depression among individuals with SCD.

Methods

Two of the three co-authors (CB and MS) developed an online survey and distributed it to colleagues working in SCD Medicine and to an international cohort of SCD clinicians through the International Spinal Cord Society (ISCoS) newsletter. It was available from March, 2020 through April, 2020 and was administered electronically (SurveyMonkey Inc, San Mateo, CA, www.surveymonkey.com). The survey was 20 questions in length and asked participants about demographic and professional information (“contextual” and “provider” characteristics, respectively) and their knowledge and beliefs about depression after SCD. We also queried how respondents screen for and treat depression in SCD and their perceptions of barriers to depression treatment.

Descriptive analysis of provider demographic, belief, and practices frequencies was conducted. Stepwise linear regression and stepwise binomial logistic regression were used to assess the strength of predictor variables. Chi-square tests were run to check for compounding variables.

No identifying information was collected and consent was implied by participants’ completing the survey. No ethics approvals were obtained or considered necessary for this project.

Results

One hundred eleven individuals participated in this survey. Fifty-seven (51.4%) identified as female (48.6% as male, none as gender fluid or non-binary), their average age was 46.7 years (range 25–75 years), they had spent an average of 19.7 years in clinical practice (range 1–50 years), and 42.3% were rehabilitation physicians (Table 1). The largest plurality of respondents worked in nations with universal/government-funded healthcare (36.9%), but others’ home countries had universal basic healthcare with available private insurance (29.7%), systems of public and private insurance (28.8%), or only self-pay for healthcare (4.5%). Nearly half (49.1%) of participants worked in developed nations, though 40.9% worked in developing nations and 10% in transitional nations.

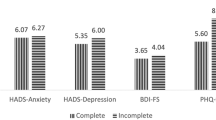

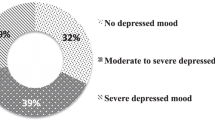

A majority of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with statements that “depression is a normal reaction to SCD” (67.5%) and that “depression is a sign of grief” (63.9%). The majority also agreed with the statement that, “I am well trained to handle depressive symptoms of SCD at the basic level” (60.3%). When participants were asked to estimate which percentage of their patients with SCD have depression, the average response was 48.7% (SD = 27.1%), and 18% of respondents gave estimates of 80% or more. Nearly two-thirds of participants (66.4%) reported either always or often screening their patients with SCD for depression. Sixty-nine (62.2%) reported using their own questions or clinical judgment to screen while the rest used a formal depression screening measure such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (12.6%), Spinal Cord Injury–Quality of Life Measure (8.1%), Patient Health Questionnaire 2 or 9 (5.4%), Beck depression inventory (3.6%), and the Zung questionnaire (0.9%) (Table 2).

When treating individuals with SCD for depression a majority of participants always or often recommended psychotherapy/counseling (88.1%) and/or a structured exercise program (68.8%), with a smaller percentage always or often recommending antidepressant medication (41.3%). Among respondents who offer their patients antidepressants, 67% used selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRIs), 23% used tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), 7% used serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), 2% used atypical antidepressants including Bupropion, and 1% used monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Slightly over half of respondents (58.7%) reported that their patients with SCD and depression always or often accept treatment for their depression, but substantial minorities had patients who only sometimes (32.1%) or rarely/never (9.2%) accepted treatment. When asked about the main barriers to depression treatment in their practices, 47.7% cited patient denial of depression while others listed stigmas that are attached to depression (41.4%) and lack of availability and high cost of psychotherapy and counseling (45.9% and 35.1%, respectively) and antidepressants (5.4% and 10.8%, respectively). Only 14.4% responded that they perceived no barriers to treatment of depression among their patients with SCD.

Linear regression analyses were used to uncover relationships between demographic and professional factors, depression-specific beliefs, and clinical practices. The belief that one is well trained to handle depressive symptoms predicted increased frequency of screening (F(1,106) = 69.851, p < 0.05; with an R2 of 0.397) and of recommending treatment with antidepressants (F(1,105) = 5.530, p < 0.05; with an R2 of 0.050), psychotherapy (F(1,105) = 8.558, p < 0.05; with an R2 of 0.075), and a structured exercise program (F(1,105) = 6.480, p < 0.05; with an R2 of 0.058). Mental health professionals were more likely to screen individuals with SCD for depression than were other types of clinicians (F(1,106) = 4.280, p < 0.05; with an R2 of 0.039), and male respondents were more likely to prescribe antidepressant medications than were female respondents (F(1,105) = 5.802, p < 0.05; with an R2 of 0.040). Participants working in developed countries were more likely to use established depression screening measures than were those working in less developed nations, χ2(2, N = 109) = 8.6, p < 0.05, and those working in countries with a system of public and private insurance were less likely to use established screening measures than were working within other health insurance systems χ2(1, N = 110) = 5.93, p < 0.05.

Chi-square analyses were run to check for confounding variables. Self-identified mental healthcare professionals were not more likely to work in economically developed countries than were other types of clinicians. The type of healthcare system in which one worked (universal coverage versus tiered systems) did not predict perceptions of cost or availability of medications or psychotherapy as a barrier to care.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated how SCD healthcare providers view, screen for and treat depression, whether their personal and professional characteristics influence their practice patterns, and what they perceive as barriers to appropriate treatment of depression. The survey yielded several interesting insights.

First, we found that contrary to expert opinion, most clinicians believe depression is synonymous with grief and a normal reaction to SCD [2]. We expected that ascribing to these beliefs would predict underutilization of depression screening and less frequent depression treatment, but we found no association between these variables.

Next, clinicians who describe themselves as “well trained to handle depressive symptoms of SCD” are more likely than those who do not to screen people with SCD for depression and to follow recommended treatment options including psychotherapy/counseling, structured exercise programs, and antidepressant medication [5]. As these practices are key for ensuring the wellbeing of individuals with SCD and co-existing depression, it may be beneficial to both include formal mental health educational content in rehabilitation medicine training curricula and to advocate for inclusion of trained mental health professionals as part of multi-disciplinary SCD treatment teams.

Third, participants in this study over-estimated the prevalence of depression among their patients with SCD. They estimated the prevalence to be more than twice as high as was found in Williams and Murray’s meta-analysis [1]. Several factors may have led to this discrepancy, including many of our respondents’ erroneous belief that depression is a normal reaction to SCD, their conflation of depression and grief, and their use of personal judgment in diagnosing depression, rather than validated screening tools. Misdiagnosis of depression may expose patients to stigma, to side effects of potentially needless medications, and to investment in unneeded and inappropriate resources. It may also lead to misuse of already scarce mental health resources [6]. By using the PHQ-9, clinicians can be more confident in their diagnosis and focus limited evidence-based treatment resources on patients who need them most and can benefit.

Lastly, nearly all our respondents reported that their patients with SCD and depression face barriers to appropriate treatment and many noted stigmas attached to depression and the lack of availability or prohibitive cost of counseling and/or medications. To our knowledge, this is the first study to document difficulties individuals with SCD may face in seeking care for coexisting depression. This finding underscores the important role SCD providers may play in advocating for and ensuring access to comprehensive mental health services and supports for their patients.

One step towards this goal is the use of reliable and valid depression screening measures. Only 37.8% of respondents use a formal screening measure and only 5.4% use the PHQ-9, the one measure that parallels DSM-5 criteria and has established validity to accurately identify major depression in people with SCI (sensitivity = 100%, specificity = 84%) [5, 7]. The PHQ-9 can also distinguish people with depression from those with normal grief after SCI [4]. The PHQ-9 can be implemented efficiently. If the patient does not endorse either of the first two items (depressed mood or anhedonia) screening can stop and major depression is ruled out [7].

Limitations

This study has several important limitations. First, our sample size was fairly small and our distribution method may have favored inclusion of academic rather than community clinicians. Second, in surveying exclusively clinicians, we were only able to gather information about their perceived barriers to care for depression, and not about actual barriers experienced by individuals living with SCD. Third, this study did not collect information on the respondent’s home country and specific professional designation within the mental health category. This being said, this study provides important insights into screening for and treatment practices related to depression in SCD, and how both may differ from recommended practice [5].

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to have queried how a variety of clinician characteristics affect screening for and treatment of depression in SCD. Our results indicate that comfort in handling depressive symptoms is associated with improved screening and treatment practices, that SCD clinicians may overestimate the prevalence of depression among their patients and conflate depression with grief, and that SCD healthcare providers perceive a number of important barriers to their patients’ ability to receive care for depression, several of which stem from a lack of mental health resources. Our findings indicate a need for education of SCD clinicians about depression and more robust investment in the psychological care of individuals with SCD.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kraft R, Dorstyn D. Psychosocial correlates of depression following spinal injury: a systematic review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2015;38:571–83.

Fann JR, Bombardier CH, Richards JS, Tate DG, Wilson CS, Temkin N. Depression after spinal cord injury: comorbidities, mental health service use, and adequacy of treatment. Arch Phys Med rehabilitation. 2011;92:352–60.

Fann JR, Crane DA, Graves DE, Kalpakjian CZ, Tate DG, Bombardier CH. Depression treatment preferences after acute traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:2389–95.

Klyce DW, Bombardier CH, Davis TJ, Hartoonian N, Hoffman JM, Fann JR, et al. Distinguishing grief from depression during acute recovery from spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:1419–25.

Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Management of mental health disorders, substance use disorders and suicide in adults with spinal cord injury: Clinical practice guideline for healthcare providers. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 2020.

Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. State-level projections of supply and demand for behavioral health occupations: 2016–2030. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis: Rockville, MD, USA; 2018. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/health-workforce-analysis/research/projections/technical-documentation-health-workforce-simulation-model.pdf (Accessed on 2020).

Bombardier CH, Kalpakjian CZ, Graves DE, Dyer JR, Tate DG, Fann JR. Validity of the patient health questionnaire-9 in assessing major depressive disorder during inpatient spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:1838–45.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Capron, M., Stillman, M. & Bombardier, C.H. How do healthcare providers manage depression in people with spinal cord injury?. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 6, 85 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-020-00333-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-020-00333-x

This article is cited by

-

Primary Care in the Spinal Cord Injury Population: Things to Consider in the Ongoing Discussion

Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports (2023)