Abstract

Study design

An online questionnaire.

Objectives

To assess the international spinal cord medicine and rehabilitation community’s utilization of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for spinal cord damage (SCD)-related pain and to determine whether approaches to SCD-related pain differ between developed and less developed nations.

Setting

An international collaboration of authors.

Methods

An on-line survey querying availability and utilization of a number of approaches to SCD-related pain was developed, distributed, and made available for 6 months. Responses were analyzed for the entire cohort and according to participants’ descriptions of their home nations’ economies.

Results

A total of 153 responses were submitted, mostly from developed nations. Nearly three quarters of subjects reported offering their patients with SCD narcotics; only 13% reported offering their patients with SCD medical cannabis. Subjects from developing countries were more likely than those from developed countries to prescribe buprenorphine (20.0% vs 15.6%; p = 0.001) and less likely to prescribe medical cannabis (0% vs 15.6%; p = 0.001) and acupuncture (4.0% vs 23.4%; p = 0.02).

Conclusions

Most spinal cord medicine clinicians employ a multimodal approach to pain. There are significant differences in utilization of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic approach to SCD-related pain between clinicians from more and less developed countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Between 64% and 88% of people with spinal cord damage (SCD) live with chronic pain [1,2,3,4]. As pain is associated with reductions in social functioning, community participation, and quality of life, it is consistently listed among the top health-related concerns of individuals living with spinal cord injury [5,6,7].

People with SCD may have nociceptive and/or neuropathic pain [8], and both may be difficult to treat [9]. Data suggest that gabapentinoids [10,11,12], botulinum toxin A [13], and antidepressants [14, 15] may ameliorate pain associated with SCD; weaker evidence supports non-pharmacologic modalities such as acupuncture, massage, and mindfulness exercises [16,17,18]. Medical cannabis may hold promise as an adjuvant therapy for pain in SCD though it remains relatively understudied with only three small trials having evaluated its efficacy [19,20,21].

Opioid use in SCD remains controversial [22, 23]. While recent guidelines for the management of neuropathic pain suggest that tramadol is an effective second-line agent [24], the authors found only weak evidence supporting use of oxycodone, whose use may be associated with unique side effects and risks. With the pendulum swing from the promotion of opioid use for chronic pain to recommending no new starts and tapering of patients off of opioids, the question arises as to what other medications and treatments clinicians are using for the management of pain in people with SCD and what are clinicians’ educational needs regarding pain management. In light of this, the objective of this study was to assess the international spinal cord medicine/rehabilitation community’s current utilization of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic approaches to SCD-related pain. A secondary objective was to determine whether prescribing patterns differ between developed and less developed countries.

Methods

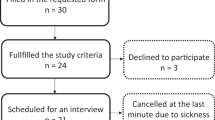

An online survey was developed and distributed (May through October of 2018) to an international cohort of clinicians who care for individuals with SCD. The survey was developed by three of the authors (MA, PWN, and TB) over several months in an iterative round of revisions. The survey was based on their clinical expertise in the field and awareness of current trends and challenges in treating SCD-associated pain. The survey was distributed by email to the authors’ colleagues in the field of spinal cord medicine, to members of the International Spinal Cord Society (ISCOS) via electronic newsletter, and to members of ISCOS-affiliated societies. The survey was available for 6 months prior to analysis.

No identifying details were collected. Consent was implied by participants’ completing the survey. No ethics approvals were obtained nor believed necessary for this project.

Descriptive analyses were performed. Responses were analyzed for the entire pool and then separated according to participants’ descriptions of their home nations’ economies. As far fewer responses were submitted from participants living in countries with developing (n = 21) or transitional (n = 4) economies than from participants living in countries with developed economies (n = 128), they were grouped into the category “developing nation”.

Results

The majority of 153 responses were submitted from Europe and Australia (41.2% and 32.0%, respectively) (Table 1); none were submitted from Africa or South America. Nearly half of subjects (47.1%) were medical doctors, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners and an additional 24.2% were physical or occupational therapists. The remaining responses came from psychologists or counselors (7.0%), nurses (6.4%), and researchers (5.1%). Just over 10% of subjects answered “other,” and represented case managers, social workers, educators, and speech and language and recreational therapists. There were no significant differences between the two groups in average years in clinic practice (15.2 developed vs 13.3 developing) or in number of encounters with patients with SCD in the preceding year (176.4 developed vs 94.2 developing).

A higher percentage of respondents from developing nations were medical doctors, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners (80% vs 43.0%; Table 1). Nearly three quarters (74.5%) of subjects reported that their patients with SCD take opioids for chronic pain (Table 2), though the percentage was higher among respondents from developed nations then among those from developing nations (82.8% vs 32.0%). Fewer participants reported offering their patients cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (53.5%), mindfulness exercises (52.2%), implanted stimulators (33.9%), buprenorphine (30.0%), yoga/tai chi (15.6%), or cannabis (13.0%) (Tables 2 and 3).

Subjects from developing countries were more likely than those from developed countries to prescribe buprenorphine (20.0% vs 15.6%; p = 0.001) and less likely to prescribe medical cannabis (0% vs 15.6%; p = 0.001) and acupuncture (4.0% vs 23.4%; p = 0.02). Differences in prescription of CBT, mindfulness exercises, tai chi or yoga, and implanted electrical stimulators did not reach significance. While only 13.1% of respondents work at a facility at which medical cannabis is prescribed, 52.3% believe that it ought to be available to patients and just under one third—including 16% from developing nations—expressed interest in learning more about its potential applications. Very few respondents felt they would benefit from additional information about a number of other modalities for treating pain.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first paper in which an international sample of clinicians caring for people with SCD was polled about utilization of a variety of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments for pain. The results may prompt further exploration of a variety of aspects of pain management.

Our first finding is that many approaches to pain are being explored and offered by our colleagues in SCD medicine. A plurality of respondents work in facilities in which buprenorphine, mindfulness exercises, electrical stimulation, and CBT are prescribed for SCD-related pain. The variety of available treatments may reflect not only the complexity of pain syndromes suffered by people with SCD but also the difficulty of achieving substantial and sustained relief. It seems that approaches to pain in SCD are often individualized and multimodal.

A second finding is that clinicians working in SCD medicine are not necessarily offering data-driven pain treatments but may, nevertheless, be tailoring their treatments to patients’ desires and subjective responses. The CanPain clinical practice guidelines addressing treatment of SCD-related neuropathic pain [24] suggest that opioid medications (tramadol and oxycodone, specifically) ought to serve as second- and fourth-line therapies, respectively, and that acupuncture, cannabinoids, and electrical stimulation “require further research.” While many complementary and alternative therapies may lack sufficient supporting data, Cardenas et al. found that a number of individuals living with SCD report that massage and acupuncture offer substantial and lasting relief from SCD-related pain [9]. This finding again underscores the difficulty of treating pain in SCD and the potential necessity of employing an “all of the above” strategy in trying to achieve relief.

A third finding is that using medical cannabis for pain relief remains controversial and that facility and governmental policies may be lagging behind clinicians’ interest in offering it to patients. Very few respondents work at a facility at which medical cannabis is prescribed but over half believe that it ought to be available to patients and a substantial minority expressed interested in learning more about its potential therapeutic benefits. These data point to a burgeoning interest in medical cannabis among clinicians in SCD medicine, a need for more educational opportunities for clinicians, and to move forward with clinical trials delineating and evaluating its effects.

Finally, it is notable that pain treatments prescribed in developed and developing nations may differ. Respondents from countries with developing economies reported that fewer of their patients are treated with opioids, and significant differences in utilization of other modalities emerged during our analyses. It is not clear whether these differences are driven by educational differences, availability of resources, or clinicians’ and patients’ cultural beliefs. Our preliminary findings present rich opportunities for further research.

Limitations

This paper has several important limitations. First, the survey was available only in English, limiting access to those who are relatively fluent in the language. Second, our distribution strategy likely resulted in selection bias, as clinicians and staff working in academic institutions or who are involved with SCD professional societies were more likely than those with fewer academic and organizational ties to receive the survey. Third, participants were not asked about their use of commonly prescribed and data-supported medications, including gabapentinoids, anti-depressants, and anti-convulsants. Finally, we received no responses from colleagues in Africa or South America and a relative paucity of surveys from individuals living in developing countries. However, this study demonstrates the complexity of managing SCD-associated pain and that most clinicians employ a multi-modal approach. It also raises the possibility that educational differences, resource availability, and cultural beliefs help shape approaches to pain management. Further research addressing these questions would be instructive.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adriaansen JJ, Ruijs LE, van Koppenhagen CF, van Asbeck FW, Snoek GJ, van Kuppevelt D, et al. Secondary health conditions and quality of life in persons living with spinal cord injury for at least ten years. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48:853–60.

Wollaars MM, Post MW, van Asbeck FW, Brand N. Spinal cord injury pain: the influence of psychologic factors and impact on quality of life. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:383–91.

Ataoglu E, Tiftik T, Kara M, Tunc H, Ersoz M, Akkus S. Effects of chronic pain on quality of life and depression in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:23–6.

Nagoshi N, Kaneko S, Fujiyoshi K, Takemitsu M, Yagi M, Iizuka S, et al. Characteristics of neuropathic pain and its relationship with quality of life in 72 patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:656–61.

Kennedy P, Lude P, Taylor N. Quality of life, social participation, appraisals and coping post spinal cord injury: a review of four community samples. Spinal Cord. 2006;44:95–105.

Lo C, Tran Y, Anderson K, Craig A, Middleton J. Functional priorities in persons with spinal cord injury: using discrete choice experiments to determine preferences. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33:1958–68.

Anderson KD. Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:1371–83.

Teasell RW, Mehta S, Aubut JA, Foulon B, Wolfe DL, Hsieh JT, et al. A systematic review of pharmacologic treatments of pain after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:816–31.

Cardenas DD, Jensen MP. Treatments for chronic pain in persons with spinal cord injury: a survey study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29:109–17.

Schug SA, Parsons B, Almas M, Whalen E. Effect of concomitant pain medications on response to pregabalin in patients with postherpetic neuralgia or spinal cord injury-related neuropathic pain. Pain Physician. 2017;20:E53–63.

Cardenas DD, Nieshoff EC, Suda K, Goto S, Sanin L, Kaneko T, et al. A randomized trial of pregabalin in patients with neuropathic pain due to spinal cord injury. Neurology. 2013;80:533–9.

Mehta S, McIntyre A, Dijkers M, Loh E, Teasell RW. Gabapentinoids are effective in decreasing neuropathic pain and other secondary outcomes after spinal cord injury: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:2180–6.

Han ZA, Song DH, Oh HM, Chung ME. Botulinum toxin type A for neuropathic pain in patients with spinal cord injury. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:569–78.

Mehta S, Guy S, Lam T, Teasell R, Loh E. Antidepressants are effective in decreasing neuropathic pain after SCI: a meta-analysis. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2015;21:166–73.

Vranken JH, Hollmann MW, van der Vegt MH, Kruis MR, Heesen M, Vos K, et al. Duloxetine in patients with central neuropathic pain caused by spinal cord injury or stroke: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 2011;152:267–73.

Estores I, Chen K, Jackson B, Lao L, Gorman PH. Auricular acupuncture for spinal cord injury related neuropathic pain: a pilot controlled clinical trial. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;40:432–8.

Norrbrink C, Lundeberg T. Acupuncture and massage therapy for neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury: an exploratory study. Acupunct Med. 2011;29:108–15.

Hearn JH, Finlay KA. Internet-delivered mindfulness for people with depression and chronic pain following spinal cord injury: a randomized, controlled feasibility trial. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:750–61.

Rintala DH, Fiess RN, Tan G, Holmes SA, Bruel BM. Effect of dronabinol on central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury: a pilot study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89:840–8.

Wilsey B, Marcotte TD, Deutsch R, Zhao H, Prasad H, Phan A. An exploratory human laboratory experiment evaluating vaporized cannabis in the treatment of neuropathic pain from spinal cord injury and disease. J Pain. 2016;17:982–1000.

Wade DT, Robson P, House H, Makela P, Aram J. A preliminary controlled study to determine whether whole-plant cannabis extracts can improve intractable neurogenic symptoms. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17:21–9.

Bryce TN. Opioids should not be prescribed for chronic pain after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2018;4:66.

Wayne NP. Severe chronic pain following spinal cord damage: a pragmatic perspective for prescribing opioids. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2018;4:65.

Guy SD, Mehta S, Casalino A, Cote I, Kras-Dupuis A, Moulin DE, et al. The CanPain SCI Clinical Practice Guidelines for rehabilitation management of neuropathic pain after spinal cord: recommendations for treatment. Spinal Cord. 2016;54(Suppl 1):S14–23.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stillman, M., Graves, D., New, P.W. et al. Survey on current treatments for pain after spinal cord damage. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 5, 14 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0160-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0160-5

This article is cited by

-

Analyzing the Impact of Cannabinoids on the Treatment of Spinal Disorders

Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine (2022)

-

Using cannabis for pain management after spinal cord injury: a qualitative study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2019)