Abstract

Introduction

Primary spinal cord tumours can lead to severe neurological complications and even death. Pregnant women often complain of discomfort of the lower limbs, which is usually caused by sciatica. Here we present the case of a pregnant woman, who was initially considered to have sciatica, but was finally diagnosed with a primary intramedullary spinal cord tumour.

Case presentation

A 28-year-old pregnant woman presented to our hospital with inexplicable numbness in her lower limbs. She was initially considered to have sciatica, but acute deterioration of neurological symptoms and plain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings suggested malignancy. The patient was finally diagnosed with a primary intramedullary spinal cord tumour at the C3–Th5 region. An emergency caesarean section was performed, after which the spinal cord lesion was evaluated using contrast-enhanced MRI, positron emission tomography with 2-deoxy-2-[fluorine-18] fluoro-d-glucose integrated with computed tomography, and spinal angiography, and further treatment was initiated. However, while the patient’s spinal cord tumour surgery was performed in early postpartum, her paraplegia and bladder and rectal disturbances remained unchanged even 1 year after surgery.

Discussion

Because of the low incidence of spinal cord tumours during pregnancy, no definite reports have been published on the treatment of pregnant patients with spinal cord tumours. Although safe imaging tests during pregnancy are limited, intervention in such patients should be performed as early as possible to avoid irreversible neurological deterioration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary intramedullary spinal cord tumours are rare neoplasms that can lead to severe neurological deterioration, poor quality of life, and even death. Due to their rarity, these tumours are often difficult to detect, leading to delays in appropriate treatment. Pregnant women often complain of discomfort in the lower limbs, which is usually caused by sciatica, cramps, or lower extremity varices. For example, a previous report indicated that ~17% of pregnant women experience sciatica during pregnancy [1]. The main symptoms of sciatica are leg pain and numbness of the lower limbs, and they can be remarkably similar to the initial symptoms of central nervous system disease. Here we report the case of a pregnant woman with primary intramedullary spinal cord tumour—the rarest subtype among spinal cord tumours—manifested by numbness of the lower limbs.

Case presentation

The patient was a 28-year-old Japanese woman, gravida 1 para 0, without past medical and family history. After natural conception, pregnancy management was performed at the obstetrical department of a nearby general hospital. The patient experienced numbness of both legs from ~20 weeks of gestation. Because the numbness did not improve, the patient visited an orthopaedic hospital for evaluation at 27 weeks of gestation. Plain lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, but no remarkable findings were observed. The patient was suspected to have sciatica, and a follow-up observation was performed. However, the numbness of both lower limbs gradually worsened. At 40 weeks and 0 day of gestation, the patient was admitted to our hospital for pregnancy and delivery management and additional evaluation of the numbness of the lower limbs, which was difficult to diagnose as only sciatica. The patient used a wheelchair because she experienced difficulty in walking. In addition to the numbness of both lower limbs, she experienced numbness in the fingertips of both upper limbs. There were no abnormalities on obstetric examinations, such as internal examination, foetal ultrasound, cardiotocogram and pelvic X-ray scan.

At 40 weeks and 2 days of gestation, we consulted neurologists. Cranial nerve abnormalities were not observed. Her neurological examination revealed weakness in the bilateral lower extremity, hypaesthesia below level Th2, hyperreflexia in patellar tendon reflex and Achilles tendon reflex bilaterally, constipation, and urinary retention; these suggested an upper spinal lesion. Because spinal paraparesis of the thoracic level was suspected, plain cervicothoracic MRI was performed. The cervicothoracic MRI revealed a spinal cord lesion through the C3–Th5 region, which led us to suspect spinal cord tumour or arteriovenous malformation (Fig. 1a). At 40 weeks and 3 days of gestation, the patient developed neck pain, bladder and rectal disturbances, as well as aggravation of both the upper and lower limbs numbness. Drip infusion of 600 mg/day of glycerol and 16 mg/day of dexamethasone were immediately started. The patient’s neck pain temporarily improved after wearing a neck collar. However, cervical pain worsened and respiratory distress appeared. Furthermore, an emergency caesarean section was performed at 40 weeks and 4 days of gestation. Considering the possibility of a spinal cord tumour, spinal subarachnoid anaesthesia was avoided and general anaesthesia was administered. The child, a girl, cried soon after birth, weighed 2379 g with Apgar Score 8/9 (dermal colour −2/−1) and umbilical arterial blood pH 7.34. Intubation management was unnecessary, but the child was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for low-birth-weight infants. The patient demonstrated good post-operative anaesthesia awakening and there was no respiratory suppression after extubation. Subsequent respiratory conditions and obstetric conditions were both good.

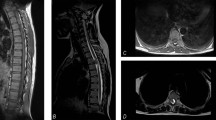

a C3–Th5 spinal cord lesion through cervicothoracic plain MRI on admission: A spinal cord tumour or arteriovenous malformation at the C3–Th5 region was suspected based on the plain MRI findings. b Cervicothoracic contrast-enhanced MRI after caesarean section: the differential diagnosis among spinal cord benign tumour, spinal cord cancer, and arteriovenous malformation was difficult by the contrast-enhanced MRI

Three days after the caesarean section, cervicothoracic contrast-enhanced MRI was performed; however, differential diagnosis among spinal cord benign tumour, spinal cord cancer, and arteriovenous malformation was difficult (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, positron emission tomography with 2-deoxy-2-[fluorine-18] fluoro-d-glucose integrated with computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) and spinal angiography were performed, and the patient was diagnosed with a primary intramedullary spinal cord tumour in the C4–Th6 region (Fig. 2). No significant change in symptoms was observed until tumour surgery. On postpartum day 20, spinal cord tumour surgery (C3–Th6 laminectomy and tumour extirpation) was performed. Pathological findings were World Health Organization grade II ependymoma. Post-surgical MRI revealed no residual tumour, and post post-operative treatment was deemed unnecessary. However, the patient’s paraplegia and bladder and rectal disturbances remained unchanged even 1 year after surgery. After rehabilitation, she was unable to transfer to a wheelchair. Urination control was difficult, as she experienced incontinence.

Discussion

The incidence rate of primary spinal cord tumour is assumed to be 0.5–2.5/100,000 per year [2]. Approximately, 10% of primary spinal cord tumours are intramedullary tumours [2], such as that in the present case, making them the rarest of neoplasms. The most common clinical symptoms of spinal cord tumour during pregnancy are numbness of the limbs and neurological deficits. It is reported that ~17% of pregnant women experience sciatica [1]. The main symptoms of sciatica are leg pain and numbness of the lower limbs, which are the same as the initial symptoms of spinal cord tumour. Therefore, the differential diagnosis of sciatica and spinal cord tumour during pregnancy must be exercised with caution.

Spinal cord tumours during pregnancy can influence tumour growth and aggravate neurological symptoms. The reasons for this include an increase of the intravascular volume, increase of the vascular bed with oestrogen and progesterone, rise of intra-spinal venous pressure, and rise of cerebrospinal fluid pressure due to the gravid uterus compressing the inferior vena cava [3, 4]. In addition, it is suggested that an increase in growth factors and angiogenic factors during pregnancy influence the rate of growth of tumours [5]. Since it usually takes several days for hormones to reach pre-gravid levels after delivery, an increased growth potential of tumours in both pregnancy and the early postpartum period may also be responsible for aggravation of the tumour [6].

Because of the low incidence of spinal cord tumours during pregnancy, no definite reports have been published on the treatment guidelines of pregnant patients with spinal cord tumours. Majority of pregnant patients with benign spinal cord tumours can postpone surgery to after delivery [6]. Close surveillance, such as re-examination by plain MRI every 3 months, is essential for conservative treatment, since sudden deterioration of benign spinal cord tumours has been observed [6]. If patients with benign spinal cord tumours experience sudden deterioration at 32–34 weeks of gestation or later, induction of delivery or a caesarean section can be considered at the time [6,7,8] (Fig. 3). Recovery after progressive neurological deficit due to rapid tumour growth during pregnancy is difficult. Moreover, if highly malignant tumours are not promptly treated during pregnancy, it may result in the death of both mother and child. For example, cauda equine syndrome is one of the main indications for urgent operative treatment during pregnancy [8]. Therefore, prepartum surgery is a choice for patients who develop malignant tumours or sudden deterioration irrespective of the gestational period, although it may lead to preterm labour or foetal damage [6,7,8] (Fig. 3). Furthermore, prepartum surgery may be considered if patients experience incapacitating pain and progressive weakness before 32 weeks of gestation [6]. After reviewing the literature, we inferred that a caesarean section may be safe, because it allows accurate cardiovascular management [6, 9]. However, there is no clear evidence that vaginal delivery poses a higher risk of aggravating neurological symptoms than caesarean section.

Sufficient preparation is of great importance for prepartum surgery. Prone position cushion should be used during the surgery to avoid decreased placental perfusion secondary to the compression of vena cava and gravid uterus in the prone position [6]. Use of anaesthetic agents, antibiotics, and analgesics should be determined considering the safety of the foetus.

Therapeutic abortion is also an option. Abortion may be permitted up to 22–24 weeks if the patient’s life is at risk. However, the decision to continue or end the pregnancy lies with the patient herself. Clinicians should inform the patient and her family about the risks between tumour growth and pregnancy, as well as the possible congenital anomalies related to various treatment options (eg, anaesthetic agents, antibiotics, analgesics, and anticancer drugs) [6].

In general, contrast-enhanced MRI is now established as the first choice in the evaluation of patients with suspected spinal cord lesions. For pregnant women, ultrasound and plain MRI are considered safer than radiographic examinations. Conversely, contrast-enhanced MRI is not recommended during pregnancy because gadolinium-based MRI contrast agents have been reported to pass through the placental barrier [10]. A recent report indicated that gadolinium MRI at any time during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of stillbirth or neonatal death [11]. Data on the safety of 18F-FDG PET/CT during pregnancy are limited. Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection in 1990 state that pregnant women as well as children under 10 years of age are considered to be highly susceptible to radiation [12]. Although pregnancy may not be an absolute contraindication of a clinically justified 18F-FDG PET scan [13], we assume that 18F-FDG PET/CT should be used only when the diagnostic benefit exceeds the disadvantage due to radiation exposure.

On admission, the patient was already experiencing inexplicable numbness of the lower limbs, which was difficult to diagnose as only sciatica. We immediately consulted neurologists and attempted appropriate countermeasures for delivery. Nevertheless, we still believe that if our intervention (eg, photographing contrast-enhanced MRI and caesarean section) had been performed earlier, the patient’s residuals may have been milder.

A spinal cord lesion was suspected in the present case, and the acute deterioration of neurological symptoms and plain MRI findings could not deny the possibility of malignancy or arteriovenous malformation. Caesarean section was then performed to evaluate the spinal cord lesion with contrast-enhanced MRI, 18F-FDG PET/CT, and spinal angiography, and to initiate further treatment. The patient was finally diagnosed with a primary intramedullary spinal cord tumour at the C3–Th5 region. However, although the patient’s spinal cord tumour surgery was performed in early postpartum, her neurological symptoms remained unchanged. This shows that intervention in such patients should be performed as early as possible to avoid irreversible neurological deterioration.

References

Hall H, Lauche R, Adams J, Steel A, Broom A, Sibbritt D. Healthcare utilisation of pregnant women who experience sciatica, leg cramps and/or varicose veins. Women Birth. 2016;29:35–40.

Karikari IO, Nimjee SM, Hodges TR, Cutrell E, Hughes BD, Powers CJ, et al. Impact of tumor histology on resectability and neurological outcome in primary intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a single-center experience with 102 patients. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:188–97.

Divers W, Hoxsey R, Dunnihoo D. A spinal cord neurolemmona in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1978;52:47–50.

Hyuga S, Sakamoto A, Kawamata T, Shimizu T, Kawamata M. A parturient who underwent resection of a spinal tumor. Masui. 2013;62:609–12.

Yust-Katz S, de Groot JF, Liu D, Wu J, Yuan Y, Anderson MD, et al. Pregnancy and glial brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:1289–94.

Meng T, Yin H, Li Z, Li B, Zhou W, Wang J, et al. Therapeutic strategy and outcome of spine tumor in pregnancy. Spine. 2015;40:146–53.

Han I, Kuh SU, Kim JH, Chin DK, Kim KS, Yoon YS, et al. Clinical approach and surgical strategy for spinal diseases in pregnant women: a report of ten cases. Spine. 2008;33:614–9.

Moles A, Hamel O, Perret C, Bord E, Robert R, Buffenoir K. Symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas during pregnancy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20:585–91.

Slimani Ol, Jayi S, Fdili Alaoui F, Bouguern H, Chaara H, Fikri G, et al. An aggressive vertebral hemangioma in pregnancy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:207.

Kanal E, Barkovich AJ, Bell C, Borgstede JP, Bradley WG Jr, Froelich JW, et al. ACR guidance document for safe MR practices: 2007. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1447–74.

Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Bharatha A, Montanera WJ, Park AL. Association between MRI exprosure during pregnancy and fetal and childhood outcomes. JAMA. 2017;316:952–6.

1990 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. Ann ICRP. 1991;2:1–201.

Zanotti-Fregonara P, Chastan M, Edet-Sanson A, Ekmekcioglu O, Erdogan EB, Hapdey S, et al. New fetal dose estimates from 18F-FDG administered during pregnancy: standardization of dose calculations and estimations with voxel-based anthropomorphic phantoms. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1760–3.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Akiko Matsunaga for comments and advice on the manuscript. We also thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fujii, K., Orisaka, M., Yamamoto, M. et al. Primary intramedullary spinal cord tumour in pregnancy: a case report. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 4, 25 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0059-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0059-6

This article is cited by

-

Fatal holocord recurrence of a pregnancy-related, low-grade spinal ependymoma: case report and review of an unusual clinical phenomenon

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2020)

-

Diagnosis and rehabilitation of a pregnant woman with spinal cord disorder due to spinal cord tumor

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2019)