Abstract

Background

High quality communication between providers and parents of seriously ill neonatal patients is vital and yet poorly understood. Feudtner summarized five challenges and seven priorities to the study and advancement of pediatric palliative care. Improvement of communication is a priority, while lack of specification and measurement of outcomes relevant to the pediatric population remains a challenge. Specifically, measurement of communication quality in pediatrics, and especially neonatology, is problematic.

Methods

We conducted a focused review of this topic which we hope will serve to support further research. We reviewed the current literature in Pubmed and searched the Palliative Care Research Cooperative (PCRC) instrument library.

Results

We found five validated instruments which met our criteria, relied on patient or surrogate report, and were developed to measure quality of communication and/or satisfaction with communication with adult patients or their surrogates. Our Pubmed search yielded 249 unique results, only two of which met our inclusion criteria.

Conclusion

We conclude that development and exhaustive testing of a validated, comprehensive measure of communication quality for the neonatal population is needed. Without such a measure, it will be difficult to advance the field and achieve high quality prognostic communication for the parents of seriously ill babies.

Impact

-

Measurement of communication quality in pediatrics, and especially neonatology, is problematic, understudied, and yet critical to the advancement of the field.

-

There has not been an overview of existing measures of communication quality in the NICU published, nor has there been a comprehensive discussion of this important topic. Our paper provides such an overview and initiates such a discussion.

-

We present a narrative review of existing measures of communication quality in the NICU in order to highlight the need for further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-quality prognostic communication between providers and parents of seriously ill neonatal patients is vital and yet poorly understood.1 In 2019, Feudtner and colleagues summarized five common challenges and seven key priorities to the study and subsequent advancement of pediatric palliative care.2 Improvement of communication for clinicians at all levels of training is a top priority, while lack of specification and measurement of outcomes relevant to the neonatal population remains a challenge. Specifically, measurement of communication quality for the purpose of research in neonatology is problematic and yet critical to the advancement of the field. For that reason, we present here a narrative review of this topic. This review is not intended to be a comprehensive systematic review. Instead, we hope this brief exploration will highlight a direction for further study.

Prior work has demonstrated that there are important functions of communication that differ between adult and pediatric contexts.3 This suggests that, even though in both cases communication often occurs with surrogates, communication with parents is meaningfully different from communication with surrogates for adult patients. In the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) setting, this difference is likely explained by unique clinical circumstances and long-term implications of medical decision-making for patients who lack any past history from which to infer preferences to inform decision-making. In addition, prognostication in the NICU can be particularly challenging due to significant limitations in the available data.4 These features also likely mean that communication with parents of critically ill neonates is different from communication even with parents of older pediatric patients. Relying exclusively on adult literature to guide how clinicians should communicate with parents of neonatal patients, especially in relation to prognosis, is therefore inadequate. Still, palliative care research involving adult patients, which often describes communication with stressed surrogates who may have some experiences in common with parents of NICU patients, can serve as a useful foundation upon which additional studies in the NICU setting can be built. Though not all communication with parents of seriously ill neonates relates explicitly to end of life, palliative care research focuses on challenging communication encounters across the full spectrum of serious illness and has produced the majority of literature in this field. This is therefore the primary source of literature that has informed our work.

One challenge to studying communication quality is the absence of a comprehensive, universally agreed upon definition of high-quality communication. Prior work demonstrates variable definitions of communication quality.5 In a 2003 review of the quality of parent–provider communication in pediatrics, 31 studies of provider–parent communication were examined, none of which utilized a validated, comprehensive measure of communication quality. The authors recommend the development of standardized and objective measures of communication quality, specific to the pediatric population.6 More than 15 years later, the problem persists, leading researchers to create their own unvalidated measures in order to study this important topic.7 Though a small number of studies have begun to investigate communication quality in pediatrics, there is not a universally agreed upon, validated, comprehensive measure of communication quality specific to the neonatal population.

Methods

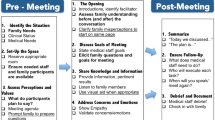

We sought to identify measures of communication quality in an effort to better understand the present state of research in this area and to support future work. We focused on measures specific to parent’s report of both objective aspects such as whether providers discussed particular outcomes or displayed certain traits and subjective aspects such as satisfaction with a conversation. We excluded measures that relied on direct observation of communication. We did this in the hopes of identifying measures that would be practically applicable in the context of clinical trials of communication interventions. Though objective measures involving observation and coding provide valuable data, they are challenging to implement on a large scale.

To identify measures, we reviewed the current literature in Pubmed and searched the Palliative Care Research Cooperative (PCRC) instrument library. Instruments in the PCRC instrument library are chosen from published systematic reviews relevant to palliative care. In order to be included, an instrument has to have been highly scored by the authors of each systematic review.8 We expanded our identification methods to find measures specific to neonatal contexts. We searched the literature using terms listed in Fig. 1. For this portion of our search, we included only measures that were rigorously validated for use in the NICU. See Fig. 1 for exclusion criteria. We also reviewed references from relevant articles identified through this search. This was not a systematic review. We present our findings to identify a gap that deserves additional investigation. For both portions of our search, we excluded publications from 1996 or earlier as outdated given that medicine, and especially neonatal medicine, has changed dramatically in the past 25 years.

Results

We queried the PCRC instrument library and found 5 validated instruments that met our criteria, relied on patient or surrogate report, and were developed to measure quality of communication and/or satisfaction with communication with adult patients or their surrogates. Our Pubmed search yielded 249 unique results, only 2 of which met our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The measures identified examined satisfaction with communication, content of communication and information transfer, and interpersonal skills, among other items. Those measures are detailed in Table 1. Of the few validated instruments to measure communication quality with parents of neonatal patients, none scored highly enough to be included in the PCRC instrument library. Identified NICU-specific measures focus on constructs, including barriers, personal relationships, and parent satisfaction, and are detailed in Table 1.

Discussion

It is not known which outcome measures are most important to the study of communication quality in the NICU. Studies suggest that a variety of factors, such as perceived compassion and provider burn-out, impact quality of communication.9,10 Results of studies focused on quality of medical communication have been contradictory and difficult to interpret.5 Measures typically focus on different characteristics and it remains unclear which are most important or most useful in the context of research. Many existing measures rely exclusively on parent/surrogate satisfaction with communication, which does not accurately reflect communication quality.5 Every scale listed in Table 1 relies, to some extent, on surrogate satisfaction. This may demonstrate bias that resulted from our choice to exclude measures that rely on direct observation. However, measures are needed from which data can be collected efficiently on a large scale. Such efficiency is not feasible when using measures requiring direct observation. While communication with parents of sick neonates is different from communication with surrogate decision-makers for adult patients, most accepted measures of communication quality have not been rigorously tested or validated in the pediatric or neonatal setting.11,12 For this study, we included validated instruments of which we were able to identify only two that were specific to neonates.13,14 Each of these has problematic limitations. The Reid scale fails to address important aspects of communication, including whether clinicians discussed future quality of life and was tested only in the first 2 weeks of NICU admission. Its applicability to other periods is not known. The Latour scale did not assess criterion validity meaning that it was not compared to an external criterion for communication quality. Neither measure has been assessed for scale responsiveness. Responsiveness describes a measure’s ability to detect changes over time or differences between groups. Given the lack of evidence regarding responsiveness, the ability of current measures to detect changes in communication quality brought about by interventions is unknown.

Our narrative review has its own limitations. Because we did not conduct an exhaustive systematic review, we cannot be certain that we identified all relevant measures. We hope to build on this work in the future and that others will use our findings to inform further study. Despite problems related to use of parent satisfaction as a measure of communication quality, many communication quality measures assess parent satisfaction in isolation or in combination with other metrics. We therefore included it in our search terms. Though our focus was on communication with parents of seriously ill neonates, we included measures from the PCRC instrument library intended for adults in order to conduct a broad and comprehensive search and capture measures identified as high quality, given the limited literature in our narrow scope. While adult measures cannot be applied to neonatal contexts without additional study, they provide a starting place for additional work.

To adequately capture quality of communication, multiple dimensions must be measured. Though adult measures cannot be applied to the neonatal setting without further research, if researchers adapt, validate, and rigorously test such measures in the neonatal setting they may prove to be useful. Consideration could also be given to validating unvalidated measures designed for the neonatal setting. The measures we identified can serve as starting points for further study. We propose development and exhaustive testing of a validated, comprehensive measure of communication quality in the neonatal setting. Without such a measure, it will be difficult to advance the field and achieve high-quality prognostic communication for the parents of seriously ill neonates.

References

Levetown, M. & American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics. Communicating with children and families: from everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics 121, e1441–e1460 (2008).

Feudtner, C. et al. Challenges and priorities for pediatric palliative care research in the U.S. and similar practice settings: report from a Pediatric Palliative Care Research Network Workshop. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 58, 909.e3–917.e3 (2019).

Sisk, B. A. et al. Communication in pediatric oncology: a qualitative study. Pediatrics 146, e20201193 (2020).

Lantos, J. D. We know less than we think we know about perinatal outcomes. Pediatrics 142, e20181223 (2018).

de Haes, H. & Bensing, J. Endpoints in medical communication research, proposing a framework of functions and outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 74, 287–294 (2009).

Nobile, C. & Drotar, D. Research on the quality of parent-provider communication in pediatric care: implications and recommendations. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 24, 279–290 (2003).

Igler, E. et al. Development and initial validation of the Communication About Medication by Providers–Parent Scale (CAMP-P). Glob. Pediatr. Health 6, 2333794X1985798 (2019).

Palliative Care Research Cooperative Group. Palliative Care Measurement Tool Library. https://palliativecareresearch.org/corescenters/measurement-core/Palliative-Care-Measurement-Tool-Library (2019).

Chang, B. P., Carter, E., Ng, N., Flynn, C. & Tan, T. Association of clinician burnout and perceived clinician-patient communication. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 36, 156–158 (2018).

Mori, M., Fujimori, M., Hamano, J., Naito, A. S. & Morita, T. Which physicians’ behaviors on death pronouncement affect family-perceived physician compassion? A randomized, scripted, video-vignette study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 55, 189–197 (2018).

Wigert, H., Dellenmark, M. B. & Bry, K. Strengths and weaknesses of parent-staff communication in the NICU: a survey assessment. BMC Pediatr. 13, 1–14 (2013).

Weiss, S., Goldlust, E. & Vaucher, Y. E. Improving parent satisfaction: an intervention to increase neonatal parent-provider communication. J. Perinatol. 30, 425–430 (2010).

Reid, T., Bramwell, R., Booth, N. & Weindling, M. Perceptions of parent-staff communication in neonatal intensive care: the development of a rating scale. J. Neonatal Nurs. 13, 24–35 (2007).

Latour, J. M., Duivenvoorden, H. J., Hazelzet, J. A. & Van Goudoever, J. B. Development and validation of a neonatal intensive care parent satisfaction instrument. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 13, 554–559 (2012).

Engelberg, R., Downey, L. & Curtis, J. R. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J. Palliat. Med. 9, 1086–1098 (2006).

Bredart, A. et al. A comprehensive assessment of satisfaction with care: preliminary psychometric analysis in an oncology institute in Italy. Ann. Oncol. 10, 839–846 (1999).

Bredart, A. et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer – satisfaction with cancer care questionnaire: revision and extended application development. Psychooncology 26, 400–404 (2017).

Meakin, R. & Weinman, J. The “Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale” (MISS-21) adapted for British general practice. Fam. Pract. 19, 257–263 (2002).

Loblaw, D. A., Bezjak, A. & Bunston, T. Development and testing of a visit-specific patient satisfaction questionnaire: the Princess Margaret Hospital Satisfaction With Doctor Questionnaire. J. Clin. Oncol. 17, 1931–1938 (1999).

Acknowledgements

A.S.K.’s work is funded by NIA K24AG062785.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author has met the Pediatric Research authorship requirements as delineated below: substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent statement

Patient consent was not required for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guttmann, K.F., Orfali, K. & Kelley, A.S. Measuring communication quality in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Pediatr Res 91, 816–819 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01522-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01522-6

This article is cited by

-

Words matter: exploring communication between parents and neonatologists

Journal of Perinatology (2022)