Abstract

Objective

To record the content and parental perceptions of family meetings in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) to improve existing frameworks for facilitating these meetings.

Study design

A prospective, mixed-methods study. NICU family meetings were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed by an iteratively derived coding framework until thematic saturation. We used descriptive statistics of parental post-meeting assessments.

Results

Qualitative analysis of 21 meetings identified both Communication Facilitators and Barriers. Facilitators included use of visual-aids and participation of social workers to clarify information for parents. Barriers included staff rarely eliciting parental comprehension (3 meetings) or concerns (5) before providing new information, resulting in 39% of parents reporting they didn’t ask questions they wanted to ask. In 33% of meetings an important participant was absent.

Conclusions

This novel qualitative and quantitative dataset of NICU family meetings highlights areas for improving communication. Attention to these components may improve parental perceptions of family meetings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Family meetings involving scheduled, private conferences between parents and members of the medical team are recommended to discuss important and complex aspects of care of sick infants and children. Parents of sick neonates in the NICU are optimal candidates to benefit from a family meeting, as the care of their infant is often long and technologically complex. Yet, while these meetings are likely the setting for some of the most important conversations between parents and their children’s healthcare team, communication with families in these meetings is rife with difficult complexities resulting from the stress of the treatment of their children [1]. The use of specific communication techniques have been shown to help mitigate some of these difficulties [2]. For instance, providing clear, consistent communication free of medical jargon, allowing time to listen to family concerns, and eliciting parental comprehension improve understanding; families value these communication skills [3,4,5,6,7,8].

Despite the importance of the family meetings and the need for evidenced based strategies for their conduct, existing frameworks and guidelines for structuring and optimizing family meetings are based mainly on expert opinion, and developed from other healthcare settings [9, 10]. Family meetings have not been adequately studied to demonstrate how evidence-based practices can improve their effectiveness [2,3,4,5, 9, 11]. This lack of data characterizing why and how meetings are conducted limits the ability to improve clinician skills and enhance parental understanding. Consequently, studies identifying deficiencies in family meeting communication and novel strategies for improving them and testing their effectiveness are needed. Finally, family experience with these meetings has also not been adequately explored.

We prospectively observed family meetings in the NICU setting in order to describe the content of these meetings through a primarily qualitative analysis targeted at identifying measurable opportunities for enhancing communication. In addition, families provided their perceptions of family meetings via a post meeting assessment to provide supplemental quantitative data, thus applying a mixed method approach to best characterize these complex exchanges.

Patients and methods

Setting and design

This is a prospective, convergent mixed-methods study of NICU family meetings that were conducted between July 2015 and October 2016. The institutional review board approved the study, which was conducted in a quaternary care NICU. Family meetings were defined as private, pre-scheduled conferences held between the medical staff and family of a neonate. Meetings were recruited via convenience sample. Informed consent was sought from all meeting participants, including medical staff. Families who did not wish to have their meetings audio-recorded were given the option of participating in the post-meeting survey alone. Only English-speaking parents were eligible to participate. A literature review of published frameworks and guidelines for family meetings was completed and used to develop a conceptual framework for assessing the utilization of established best practices. Meeting recruitment continued until qualitative analysis of meeting content themes showed a saturation point had been reached, which was anticipated to be 20–30 meetings [12].

Patient characteristics, such as age and birth weight, were collected from the medical record, and the physician leading the meeting provided the meeting purpose. At the time of the meeting, a handheld audio recording device was placed in the room and turned on by a research team member, who then left the room. The recording was stopped at the conclusion of the meeting. Recordings were transcribed by a professional medical transcription service and then destroyed after the research team verified transcript accuracy.

Immediately following the meeting, parents were asked to complete the post-meeting assessment. The assessment was designed to elicit parental perspectives about his or her satisfaction with the meeting and its effectiveness in addressing their questions and concerns. The post-meeting assessment consisted of a 12-item survey including 4-point Likert scale and open-ended questions. The authors assessed content-validity by reviewing the survey items with five English-speaking parents in the NICU, who did not participate in the study. In response, minor revisions were made to enhance clarity. Due to a lack of variability in the survey items and a paucity of responses to open-ended questions in the first 18 completed written surveys, surveys were verbally conducted for the final four sets of parents.

Data analysis

Qualitative analysis of meeting transcripts was conducted using a modified grounded theory [12, 13]. Two coders (MD and MM) analyzed transcripts independently by reading each transcript and iteratively assigning individual verbatim statements, such as parental questions or meeting interruptions, “incident” codes. After each transcript was coded independently, coding was compared, and all discrepancies were discussed and resolved to the satisfaction of both investigators. Codes were grouped into abstract categories based on content, and then organized under overarching themes.

In order to quantify the amount of dialog contributed by each meeting participant, as percentage of total transcript coverage, we divided the total number of characters in the words spoken by each participant by the number of characters in the meeting transcript. Each meeting transcript was also reviewed to determine whether the person leading the meeting asked parents to share their questions, perceptions, or concerns before providing a substantial amount of medical information to the parents.

Parental answers to free response survey questions were reviewed by MD and categorized by theme. Descriptive statistics were used for Likert scale survey questions. Quantitative and qualitative data were merged after data collection to integrate findings and achieve the primary objective of characterizing family meeting content.

Results

Meeting purpose, characteristics, and patient demographics

During the study period, 62 family meetings were identified. In 30 cases, the family meeting met inclusion criteria, and an investigator was available to seek consent and arrange audio recording. Twenty-two of these 30 parents agreed to participate. In all cases, the health care providers involved in the meeting consented to the study. One family did not wish to have their meeting audio-recorded, but agreed to complete a post-meeting survey, leaving 21 family meetings recorded for analysis.

The purpose for these meetings fell into 5 categories. Eight of 22 meetings were held to facilitate medical decision-making, for example to discuss need for a tracheostomy. Eight were to provide families with information about the infant’s diagnosis or prognosis, for example to discuss new findings on head ultrasound. Three meetings were for discharge planning, two meetings were goals of care discussions, and two were due to a family request for an update on their child’s condition. Demographic characteristics of the patients, as well as the parents who completed post-meeting assessments, are included in Table 1.

Meeting transcript qualitative analysis

Meeting transcripts yielded 918 individual statements that were coded into 15 incident codes, shown in Table 2. Codes encompassing similar constructs were then grouped under 6 categories: encouraging dialog, informational clarifiers, emotional validation, procedural barriers, informational detractors, and emotional barriers. These categories were then grouped into two overarching themes of Communication Facilitators and Communication Barriers.

Meeting transcript quantitative analysis

Meeting characteristics and the frequency of specific incident codes are shown in Table 3. The medical team elicited family input in every meeting and parents asked questions during every meeting. However, in only three recorded meetings did a medical team member ask for parental comprehension of their child’s condition before providing substantial new information to the family. In only five meetings did the family voice their questions and concerns before the physician began providing substantial new information.

Families contributed 24% of all meeting dialog (range 12–39%), and asked a median of 18 questions per meeting. In eight meetings, a social worker intervened in the communication process at least once to help clarify information for parents. For example, a social worker asked a mother: “Did you hear what she just said? He [infant] has proven to us when he is calm and he feels good that we can wean his oxygen. That is crucial. That means a lot.”

Interruptions, such as cell phones ringing or staff coming and going during the meeting, were noted in ten meetings. Participants that were expected to be present, or were stated to be the appropriate people to direct questions to or update the family on certain issues, were not present in seven meetings. Finally, in 15 meetings medical staff made statements regarding medical information of the neonate that was inaccurate or not fully informed. For example, Neonatal Attending: “His main problem since then is the fact that he has needed a ventilator in the past and he does need oxygen. He has an oxygen requirement, right?”

In 11 meetings, reference was made to the potential value of a visual aid in the form of a picture, radiographic image, or physical model like a gastrostomy tube. For example, “Surgery Attending: I know, it really sounds scary, but I am sure we will be able to bring you a doll or pictures.” Out of these 11 meetings, the visual aid was actually available in only 5.

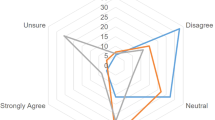

Parental perceptions of family meetings

Post-meeting assessments were completed for 22 meetings, 18 in the form of the written post-meeting survey, and 4 conducted verbally. Survey responses are shown in Table 4. While 21 respondents agreed that most or all of their questions were answered in the meeting, 11 (50%) parents reported that there was at least one question that they wanted to ask, but did not ask, during the meeting. Five of these parents reported feeling too nervous or under-prepared to ask the question; while the other six felt the question was unanswerable. For example, because the proper person to direct their question to was not present at the meeting.

When asked, “What would have made this meeting more helpful to you?” 11 (50%) parents offered no suggestions. The other 50% of parents reported that either having certain medical team participants be present at the meeting, such as a consultant, (6 parents) or allowing for better parental preparation for the meeting, such as helping parents not feel nervous (2 parents) or more timely scheduling of meetings (3 parents), would have made the meeting more helpful. In addition, 6 (27%) parents reported that they had different expectations for the meeting due to different perceptions about the condition of their child than what was discussed in the meeting. For example, one responded, “When new information seems so different from what I thought I had been hearing daily, I start thinking “were they hiding this?” and it makes it harder to process.” Another stated “…it seemed like everything is trending in the right direction and then this just came out of nowhere. There have been meetings in the past where I went in and came out understanding or being more clear, but this particular one I don’t know.”

Conceptualization of a more robust framework

Based on the conceptual framework that resulted from the literature review conducted during study development, recommended best practices were compared to our results, and components of the framework that were supported by our findings are described in Fig. 1. Components suggested as important in our research findings from parental feedback are also highlighted.

Discussion

In this prospective, convergent, mixed-methods study of NICU family meetings, we were able to identify specific opportunities to improve the extent to which meetings conform to published guidelines that consistently recommend specific meeting preparation, procedures, and follow-up [3, 10, 11, 13, 14]. Further, our data identifies opportunities to correct communication deficiencies within NICU family meetings and demonstrates how these deficiencies lead to poor parental perceptions of communication. We believe this to be useful for quality improvement initiatives centered around communication, family centered care, and improving family satisfaction with NICU care.

Experts have outlined steps to take during family meetings in other settings that may help facilitate effective communication, such as eliciting family perceptions, concerns and understanding early in the meeting [2, 3, 10, 11, 13,14,15,16]. Such practices would likely benefit the 27% of parents in our study that reported a different perception of their child’s care compared to the conversation that occurred during their family meeting. Yet, few clinicians in our study asked parents to share their understanding or perceptions prior to delving into medical information and, thus, missed the opportunity to frame that information within the parent’s understanding of their child’s illness. Parent feedback suggested that having a different perception of their child’s condition than what was presented may have impacted their processing of that information.

Guidelines also support proper preparation for family meetings by medical staff [2, 3, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. This preparation should include coordination of meeting time, place and participants, as well consensus on the medical facts. In a third of all meetings in our study a participant that was expected at the meeting, or was deferred to for answering questions or discussing information, was noted to be absent. The absence of these participants, the frequency of interruptions and the misstatements made by the medical team demonstrate a need for medical staff to better prepare for family meetings. Meeting preparation might be improved by following recommendations to review pertinent medical details, elicit from families who they wish to have present at the meeting, and ensure participants can be present for the duration [3, 10, 13].

Recommendations also encourage active family participation in meetings [5, 6]. Similar to other published studies, we found that medical staff dominated dialogue in family conferences [15,16,17]. While it is impossible to determine an optimal ratio of medical staff to family dialogue, families report they appreciate being listened to [18]. We found that parents asked a median of 18 questions per meeting, but half of surveyed parents still report having questions that they wanted to ask, but did not do so. This parental perception supports the need for clinicians to listen more during family meetings and to more actively encourage parental participation.

Strategies used to encourage family participation include inviting families to share, in their own words, what they understand about their child’s condition, what their concerns are, asking them to restate what they have heard during the meeting, and posing possible questions families may be considering such as, “Some families like to ask how this may affect their child’s chance of survival. Is this something you are wondering about?” [19]

One strength of our study design is the integration of our qualitative analysis of family meetings with quantitative data of parental perceptions of those meetings to highlight for neonatal providers opportunities to improve meeting communication. Specific important areas include: (1) Staff preparation, (2) Parental preparation, (3) In-meeting communication. Staff preparation includes having all needed staff present and primed to each participate effectively in the meeting. For example, our study showed that social workers helped families process information in 8 of 21 meetings.

While other data have suggested the need to improve the inclusion and participation of multidisciplinary staff such as social workers in family meetings, how to best integrate their skill set remains a gap in knowledge [17]. Our findings suggest that a key role for multidisciplinary staff in family meetings is information processing and clarification. Awareness of this role may help improve the inclusion and participation of social workers in NICU family meetings. In addition, parents in our study reported a desire to be better prepared for meetings in order to make processing information less difficult. This observation presents another opportunity for social workers or other multidisciplinary staff to help parents prepare for family meetings, beyond merely facilitating scheduling of family meetings. Social workers can give parents a familiar presence, relieving parental anxiety, and eliciting family perceptions, questions, and needed participants prior to the family meeting. Having parents write out questions, concerns and requested participants with social workers or other individuals ahead of time may also help the medical team prepare for the meeting.

In 11 of our meetings, reference to a visual aid to enhance verbal communication was made, but the actual item or image was available in less than half of these occurrences. Providing additional resources to families, such as visual aids, is recommended to promote a family’s understanding of information [4, 20]. It may be useful for NICU staff to create digital copies of visual aids for use during family meetings, or have a repository of links to online resources that can readily be accessed during meetings and shared for families to reference after meetings as well. While the contents may vary depending on the patient population, the aid should include diagrams or photographs of equipment such as tracheostomies or G-tubes, and/or diagrams to help explain common medical processes such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia or retinopathy of prematurity.

Limitations to this study include the single center structure and convenience sample of participants. Despite this limitation we had a broad range of family meeting types, medical providers, and family members represented in our sample. Parental communication with staff was not assessed outside of family meetings aside from reported presence of parents on work rounds. In order to naturally capture the variability of family meeting use, what was determined to be a meeting was subject to variability depending on medical team discretion, for example some providers may have chosen to have an informal bedside discussion with parents, which would not have met our criteria as being a prescheduled, private family meeting. Bedside family meetings have been described in other settings, but the open bay design of the NICU in our study and neonates not being active participants makes the frequency of these meetings less likely [21]. Meetings were not videotaped and nonverbal communication was not accounted for. Subjects were aware of being audio-recorded, which could have altered their behavior. We did not include non-English speaking families, and thus our data did not add to previous reports of how language barriers may complicate family meetings [22].

Due to lack of previously published data on NICU specific family meetings, and the frequency of family meetings in our unit, we felt a convergent mixed-methods design and merged integration of qualitative and quantitative data, with an emphasis on qualitative data collection and analysis, would best provide the ability to conduct an exploratory analysis to characterize NICU family meetings. Future directions should include quality improvement initiatives to analyze how implementing standardized family meeting formats and best practices can impact the frequency of communication deficiencies and parental perceptions of family meetings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this mixed-methods study identifies multiple strategies for neonatal providers to enhance family meetings by applying frameworks for conducting family meetings published in other settings. These include increased parental preparation prior to meetings, the consistent elicitation of parental concerns and perceptions early in meetings, and structured utilization of visual aids. Additionally, novel ways to integrate interdisciplinary staff are provided. While parents report a high level of satisfaction and comprehension of the information conveyed during family meetings, parents report the need for better preparation and participation in family meetings that should be considered. Application of our composite framework for holding a NICU family meeting may be helpful to NICU providers engaged in quality improvement around family centered care at their institutions.

References

Wigert H, Dellenmark-Blom M, Bry K. Strengths and weaknesses of parent-staff communication in the NICU: a survey assessment. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:71.

Back A, Arnold R, Tulsky J. Conducting a family conference. Mastering communication with seriously ill patients. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Hudson P, Thomas T, Quinn K, Aranda S. Family meetings in palliative care: are they effective? Palliat Med. 2009;23:150–7.

Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–78.

Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Goss CH, Curtis JR. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1679–85.

Michie S, French D, Allanson A, Bobrow M, Marteau TM. Information recall in genetic counseling: a pilot study of its assessment. Patient Educ Couns. 1997;32:93–100.

Shaw A, Ibrahim S, Reid F, Ussher M, Rowlands G. Patients’ perspectives of the doctor-patient relationship and information giving across a range of literacy levels. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:114–20.

Lamiani G, Meyer EC, Browning DM, Brodsky D, Todres ID. Analysis of enacted difficult conversations in neonatal intensive care. J Perinatol. 2009;29:310–6.

Powazki R, Walsh D, Hauser K, Davis MP. Communication in palliative medicine: a clinical review of family conferences. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:1167–77.

Janvier A, Barrington K, Farlow B. Communication with parents concerning withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining interventions in neonatology. Semin Perinatol. 2014;38:38–46.

Fox D, Brittan M, Stille C. The Pediatric Inpatient Family Care Conference: a proposed structure toward shared decision-making. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4:305–10.

Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999.

Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Nelson EL, Shannon SE, Treece PD, et al. Studying communication about end-of-life care during the ICU family conference: development of a framework. J Crit Care. 2002;17:147–60.

Baile WF. SPIKES–a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5:302–11.

Singer AE, Ash T, Ochotorena C, Lorenz KA, Chong K, Shreve ST, et al. A systematic review of family meeting tools in palliative and intensive care settings. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33:797–806.

McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Shannon SE, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1484–8.

Boss RD. Family conferences in the Neonatal ICU: observation of communication dynamics and contributions. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;33:642–6.

Van Dongen JJJ, de Wit M, Smeets HWH, Stoffers E, van Bokhoven MA, Daniëls R. “They are talking about me, but not with me”: a focus group study to explore the patient perspective on interprofessional team meetings in primary care. Patient. 2017;10:429–38.

Nelson JE, Walker AS, Luhrs CA, Cortez TB, Pronovost PJ. Family meetings made simpler: a toolkit for the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2009;24:626.e7–626.e14.

Levetown M. Communicating with children and families: from everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1441–e1460.

October TW, Watson AC, Hinds PS. Characteristics of family conferences at the bedside versus the conference room in pediatric critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:3135–e142.

Thornton JD, Pham K, Engelberg RA, Jackson JC, Curtis JR. Families with limited English proficiency receive less information and support in interpreted intensive care unit family conferences. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:89–95.

Acknowledgements

Supported by The Beryl Institute Patient Experience Grant to MD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MD substantially contributed to study design, data acquisition, interpretation, and writing of the initial manuscript draft as well as approved the final manuscript as submitted. JML substantially contributed to study design, data acquisition, data analysis and approved the final manuscript as submitted. JH substantially contributed to data analysis and approved the final manuscript as submitted. GEH substantially contributed to study design, data analysis and approved the final manuscript as submitted. MCM substantially contributed to study design, data acquisition, data analysis and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted with the approval of the Columbia University Medical Center Internal Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Drago, M., Lorenz, J.M., Hammond, J. et al. How to hold an effective NICU family meeting: capturing parent perspectives to build a more robust framework. J Perinatol 41, 2217–2224 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01051-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01051-4

This article is cited by

-

Words matter: exploring communication between parents and neonatologists

Journal of Perinatology (2022)