Abstract

Background

Prenatal factors might have some health impacts later in life. This study aims to systematically review the current literature on the association between season and month of birth with birth weight as well as with weight status in childhood.

Methods

The search process was conducted in electronic databases, including papers published until April 2019 in ISI Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. The following search strategy was used with MeSH terms: (“Seasons”[Mesh]) AND (“Obesity”[Mesh] OR “Pediatric Obesity”[Mesh] OR “Obesity, Abdominal”[Mesh] OR “Overweight”[Mesh] OR “Birth Weight”[Mesh] OR “Body Height”[Mesh]). After the selection process, 50 papers were included in this systematic review.

Results

This review showed that individuals who are born in cold season (winter month) have higher body mass index (BMI) and weight in childhood. Birth in March was associated with lower weight and BMI in boys according to most studies. All studies, except one of them, showed that season/month of birth was not associated with birth weight.

Conclusions

This systematic review confirms a relationship between season and month of birth with birth weight and body size in childhood; however, the impact of confounding factors, for example, vitamin D status, should be considered in the underlying pathway of this association.

Impact

-

The results provide evidence for the effect of season and month of birth on body size in childhood.

-

Our systematic review suggests that there is no pattern between birth weight and season/month of birth, and the occurrence of low birth weight was more frequent among infants who were born in summer than others.

-

Further research should focus on identifying the impact of confounding factors, for example, vitamin D status in the underlying pathway of this association.

-

There was response to the controversial findings about the effect of environment factors, such as season and month of birth, and future anthropometric indices, such as obesity, weight, height, and birth weight.

-

Obesity is a complex and multifactorial disorder; the findings of the current study would be useful in determining the relationship pathway between the season and the month of birth with other underlying factors for childhood obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Childhood obesity is one of the most important global health problems, and associated with several short- and long-term health hazards, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and fatty liver disease.1 Although obesity is attributed to the combination of a sedentary lifestyle and excess energy intake, and biological factors, its predisposing factors are not well understood. Childhood obesity is a public health problem even in developing countries.2 The role of genetic factors has been emphasized in family and twin studies,3,4 but it is not clear to what extent individual susceptibility interacts with lifestyle and other contextual factors in the development of overweight and obesity.5 The evidence is increasing and suggests that environmental factors during early life may influence the development of obesity.6,7,8

Season of birth is one type of natural experiment that can help generate candidate environmental factors. Certain exposures tend to fluctuate in a regular fashion within a year, while, at the group level, other environmental and genetic factors remained relatively stable.9 Season and month of birth provide direct support for the “fetal origins of adult disease hypothesis” that intrauterine exposures (independent of genetic effects) may have impacts on health later in life.10,11 Evidence showed the effect of seasonal variations in pre- and postnatal infant growth.12 One study reported that infants born in summer had a higher risk of high birth weight compared with those born in winter.13 The results of a study in ∼500,000 participants in China showed shorter leg lengths in individuals born in February–August, and increased waist circumference (WC) in individuals born in March–July.11

Another study indicated that infants born in March and September have a higher risk of obesity than infants born in October and November.14 The effects of seasonality of birth on body mass index (BMI) later in life have yielded inconclusive results. In a Canadian study, winter is the peak season for adults’ BMI.5 In the British study, the first 6 months of the year,3 and in a Chinese study spring and summer,7 are the peak season for adults’ BMI, but studies from Finland and the United Kingdom found no seasonal variation in adult BMI.15 Therefore, the importance of seasons and months of birth on pre- and postnatal BMI from other studies has been controversial; the aim of this study is to systematically review and summarize the scientific literature on the associations between season/month of birth on birth weight and body size later in life.

Materials and methods

This review was designed in accordance with the protocols of systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA).

Search strategy

The search process was conducted in electronic databases, including papers published until 24 April 2019 in ISI Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar using the following keywords: (seasons OR season OR seasonal OR “season of birth” OR seasonality OR “month of birth” OR “month-of-birth” OR “birth month” OR month) AND (obesity OR “body mass index” OR weight OR “body weight” OR “overweight” OR “body size” OR adiposity OR “body fatness” OR “BMI” OR fatness OR “body size” OR obese OR “waist circumference” OR “adipose tissue” OR “waist-to-hip ratio” OR “waist-to-height ratio” OR “waist to hip ratio” OR “waist to height ratio” OR “waist–hip ratio” OR “waist hip ratio” OR height OR “leg length” OR “birth weight”) AND (birth) and a combination of them.

All elements were searched using both controlled vocabulary terms (Medical Subject Headings) and free-text words. The following search strategy was used with MeSH terms: (“Seasons”[Mesh]) AND (“Obesity”[Mesh] OR “Pediatric Obesity”[Mesh] OR “Obesity, Abdominal”[Mesh] OR “Overweight”[Mesh] OR “Birth Weight”[Mesh] OR “Body Height”[Mesh]).

Hand searching

To increase the sensitivity and to select more studies, the reference list of the published studies was checked as well.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all cross-sectional, case–control, and longitudinal studies on the relationship between season and month of birth with weight, height, and obesity in children and adolescents and birth weight in neonates. We did not consider any time or language limitation.

Limitations were applied to exclude conference papers, editorials, letters, commentary, short survey, and note.

Data management

We used EndNote program for managing and handling extracted references that were searched from databases. Duplicates were removed and entered into a duplicate library.

Study selection strategy

In the systematic search, 20,717 unique references were identified (Fig. 1). Of them, 20,125 were excluded on the basis of the title and abstract. For the remaining 592 articles, the full text was retrieved and critically reviewed. After the selection process, 50 papers were included in this systematic review.

Data collection process

Data extraction and abstraction and quality assessment

Two independent reviewers (Z.H. and M.K.) screened the titles and abstracts of papers, which were identified by the literature search, for their potential relevance, or assessed the full text for inclusion in the review. In the case of disagreement, the discrepancy was resolved in consultation with an expert investigator (R.K.).

The quality of the articles was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for cohort and cross-sectional studies.16 This quality scale contained three sections on which a maximum of 9 points was given: the items patient selection (max. of 4 points), comparability (max. of 2 points), and outcome (max. of 3 points). The qualitative scores for each study are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Results

In this systematic review, we studied the association between month and season of birth with weight, height, and obesity in childen and adolescents, and we also considered the effect of season or month of birth on birth weight in neonates. Different outcomes such as birth weight, weight (weight Z-score), BMI, overweight/obesity, and height (height Z-score) were studied. Among all included studies, 13 studies provide information on month of birth, 17 studies on season of birth, and 25 studies on both season and month of birth and body size outcomes. The study design and characteristics for all included studies according to the outcome (body size or birth weight) are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The association between month and season of birth with weight, height, and obesity is shown in Table 1, and characteristics of included studies on birth weight are presented in Table 2.

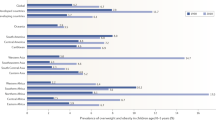

Included studies have been conducted in different countries across the world.

Effects of season and month of birth on weight, overweight, and obesity

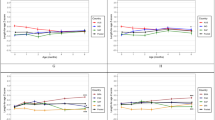

In most studies, there was a significant relation between season/month of birth and intended outcome, but in two studies, no significant relationship was observed.14,17 According to most studies, birth in the spring season (March) was associated with higher weight and overweight/obesity in both sexes.3,7,18,19,20,21 However, several studies showed that those who were born in cold season (winter month) had higher BMI and weight.5,22,23,24,25 Also, those born in March were associated with low weight and BMI, especially in boys, according to most studies.14,18,23,26 According to the frequency of studies, the lowest weight and BMI were observed among girls who were born in December (Table 1; Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2).

Quality assessments of included studies were as follows:

The results of the quality assessment of the studies showed that the articles were generally of good quality. Only 11% of articles had scores of 4 and 5, and about 90% of papers received a score >5. Overall, 43% of articles had a score >7.

Effects of season and month of birth on child’s height

Among all studies on height, in three studies, no significant relationship between season/month of birth and height was observed.27,28,29 The occurrence of short stature in those who were born in cold seasons (winter) was more likely based on the frequency of studies. However, a study by Krenz-Niedbala et al.30 showed that those who were born in cold season (born from October to April) were taller than those who were born from May to September. Also, studies by Henneberg and Louw22 and Puch et al.31 reported that short stature was more frequent among hot season-born individuals (Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4).

Effects of season and month of birth on birth weight

According to most studies, the occurrence of low birth weight was more frequent among infants born in summer than others. No pattern was observed for the association between high birth weight and season/month of birth (Table 2; Supplementary Figs. S5 and S6). Overall, only one study showed that season/month of birth was not associated with birth weight.32

Discussion

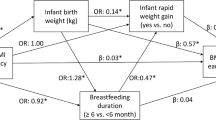

This systematic review evaluated the relationship between season and month of birth on obesity, weight, and height and birth weight. Several studies have assessed the effects of season and month of birth on BMI categories. A study by Lv et al.7 on 487,529 Chinese men and women reported that month of birth was independently associated with both BMI and WC. Birth months in which subjects had higher measures of adiposity were March–June for WC and March–July for BMI. The findings of this study suggest that adults born in spring and early summer had higher WC and BMI. A study in Hertfordshire, United Kingdom, indicated that men born after winters using average temperatures of December and January were more likely to have a higher BMI in adult life.3 The Canadian study also reported seasonal effects on obesity in adult life, and subjects born in winter/spring were more likely to be morbidly obese (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2).5 In another study, the effects of season of birth on adult WC and BMI were shown.20 The season-of-birth pattern that has been most commonly described is higher rates of obesity in individuals born in winter–spring;18,33 however, different patterns in different age cohorts have also been described.5 One study that was conducted on Japanese school children (6–15 years) showed that, because of the increase in the number of adipose tissues during the cold conditions, birth weight and early exposure to cold conditions have an association with obesity during adulthood.18

Another study in 1322 children at the age of 8 years (born in 1999 and examined in 2007) showed that the ultraviolet B–vitamin D mechanism is responsible for the season-of-birth effect on later body size.30 A previous study found adult obesity to be associated with low vitamin D during the second or third trimester of pregnancy.34 Another study showed that there was a significant interaction of race by season of birth in the levels of weight gain in early infancy, and there was no relationship between season of birth and early infancy weight gain with sex, first-born status, birth weight, study site, or initiation of breastfeeding.12 Other studies from Finland and the United Kingdom found no interaction between seasonal variation and adult BMI.14,32 It is possible that the seasonality of birth in later BMI will emerge in adulthood and is not present in childhood; however, no previous study examined this. Only the Canadian study found no seasonal variation in BMI among children aged 12–19 years.5 However, the study was cross-sectional and did not include a follow-up of the children later in life.

In the current study, we observed an association between season and month of birth with infant height. The occurrence of short stature in those who are born in cold seasons (winter) was more likely based on the frequency of studies. In a study among children aged 6–15 years in Tokushima, Japan, height gradually decreases until March (from spring to winter) and then increases from April, and reaches a peak in May or June; therefore, height was influenced by variation in month and season of birth.18

A study by Krenz-Niedbala et al.,30 in Poland, among 1322 children aged 8 years showed that those who were born in cold season (born in October–April) were taller than those in May–September;30 also, studies by Puch et al.31 among 4672 girls aged 5–18 years, and Henneberg and Louw22 among 1522 school children aged 6–18 years in Africa, showed that short stature was more frequent among individuals born in hot season. A study on children born in May through October was found to be lighter than those born in November through April. Another study on 562 girls and 546 boys in Bolivia demonstrated that children born during February–May (the rainy season) were shorter, while children born during the end of the dry season and the start of the rainy season (August–November) were taller.23

Various mechanisms may explain these effects, including changes in the force of gravity or electromagnetic field, global factors (e.g., the total amount of energy reaching the earth acting through ultraviolet-dependent production of vitamin D, hemisphere-related climatic conditions) (e.g., solar radiation, rainfall, hours of insolation, day length, and temperature), and other environmental factors (e.g., physical activity or nutrition) or cultural influences.10,31 On the other hand, exposure to sunlight and in utero vitamin D exposure are the important mechanisms that can have an effect on season of birth and child’s height. In the present systematic review, we observed that there is no pattern between birth weight and season/month of birth, and according to most studies, the occurrence of low birth weight was more frequent among infants who were born in summer than others.

Limitations of the study

Our review faces some limitations. Although controlled trials support the role of maternal 25(OH) vitamin D as the causal mechanism in the association of season of birth and birth weight,35 controversial results are reported in other studies.36,37 Therefore, it is likely that additional mechanisms specific to certain environments may also play a role, yet the physiological processes behind the resulting impact on birth weight remain unclear. Vitamin D is important for bone development and may act as a rate-limiting factor for growth. In accordance with the results of the studies in the present systematic review, births in winter and cold seasons may increase the risk of overweight and obesity in individuals. Although there are prospective and longitudinal (cohort) studies in the present systematic review, there are some factors that may affect the relationship between season and month of birth with birth weight and body size, such as air temperature and climate change.38,39,40 Geographic differences, latitudes, and ethnic differences, as well as the possible role of confounding factors in the relationship between levels of sunlight exposure and subsequent levels of vitamin D should also be taken into account. Consequently, the exact determination of the relationship between exposure and outcomes of this review becomes difficult. In addition to the possible role of the above-mentioned factors, it may also be necessary to consider the cohort or even period effect to determine the relationship pathway between season and month of birth and BMI.41,42,43,44,45,46 In spite of these limitations, this review provides comprehensive information on the association of season of birth with future weight status.

Conclusion

The results of the studies included in the present systematic review showed that children who were born in cold seasons have a higher BMI than those born in other seasons. However, given the possible role of confounding factors in the relationship between season and month of birth with birth weight and body size, we suggest assessing vitamin D levels and other potential confounding factors in future studies. The current findings should be confirmed by future longitudinal studies.

Effects of season and month of birth on weight, overweight, and obesity

This review showed that individuals who are born in cold season (winter month) have higher BMI and weight in childhood.

Effects of season and month of birth on child’s height

We observed the relationship between season and month of birth with infant height. The occurrence of short stature in those who are born in cold seasons (winter) was more likely based on many studies.

Effects of season and month of birth on birth weight

All studies, except one of them, showed that season/month of birth was not associated with birth weight.

References

Kelishadi, R. & Azizi-Soleiman, F. Controlling childhood obesity: a systematic review on strategies and challenges. J. Res. Med. Sci. 19, 993–1008 (2014).

Kelishadi, R. Childhood overweight, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. Epidemiol. Rev. 29, 62–76 (2007).

Phillips, D. I. W. & Young, J. B. Birth weight, climate at birth and the risk of obesity in adult life. Int. J. Obes. 24, 281–287 (2000).

Viner, R. & Cole, T. Who changes body mass between adolescence and adulthood? Factors predicting change in BMI between 16 year and 30 years in the 1970 British Cohort. Int J. Obes. (Lond.). 30, 1368–1374 (2006).

Wattie, N., Ardern, C. I. & Baker, J. Season of birth and prevalence of overweight and obesity in Canada. Early Hum. Dev. 84, 539–547 (2008).

Gluckman, P. D., Hanson, M. A., Cooper, C. & Thornburg, K. L. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 61–73 (2008).

Lv, J. et al. The associations of month of birth with body mass index, waist circumference, and leg length: findings from the China Kadoorie Biobank of 0.5 million adults. J. Epidemiol. 25, 221–230 (2015).

Swinburn, B. A. et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 378, 804–814 (2011).

McGrath, J. J. et al. Seasonal fluctuations in birth weight and neonatal limb length; does prenatal vitamin D influence neonatal size and shape? Early Hum. Dev. 81, 609–618 (2005).

Day, F. R., Forouhi, N. G., Ong, K. K. & Perry, J. R. B. Season of birth is associated with birth weight, pubertal timing, adult body size and educational attainment: a UK Biobank study. Heliyon 1, e00031 (2015).

Fall, C. H. Fetal malnutrition and long-term outcomes. Nestle Nutr. Inst. Workshop Ser. 74, 11–25 (2013).

Jonge, Lv. Hd, Waller, G. & Stettler, N. Ethnicity modifies seasonal variations in birth weight and weight gain of infants. The. J. Nutr. 133, 1415–1418 (2003).

Chodick, G., Shalev, V., Goren, I. & Inskip, P. D. Seasonality in birth weight in Israel: new evidence suggests several global patterns and different etiologies. Ann. Epidemiol. 17, 440–446 (2007).

Hackett, A. F., Stott, T. A., Boddy, L. M. & Stratton, G. Is air temperature at birth associated with body mass index in 9–10 year-old children? Ecol. Food Nutr. 48, 123–136 (2009).

Jensen, C. B., Sørensena, T. I. A. & Heitmann, B. L. No seasonality of birth in BMI at 7 years of age. Early Hum. Dev. 103, 129–31. (2016).

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm [cited 2009 Oct 19].

Tornhammar, P. et al. Season of birth, neonatal vitamin D status, and cardiovascular disease risk at 35 y of age: a cohort study from Sweden. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 99, 472–478 (2014).

Tanaka, H. et al. Correlation of month and season of birth with height, weight and degree of obesity of rural Japanese children. J. Med. Invest. 54, 133–139 (2007).

McGrath, J. J., Saha, S., Lieberman, D. E. & Buka, S. Season of birth is associated with anthropometric and neurocognitive outcomes during infancy and childhood in a general population birth cohort. Schizophrenia Res. 81, 91–100 (2006).

Soreca, I., Cheng, Y., Frank, E., Fagiolini, A. & Kupfer, D. J. Season of birth is associated with adult body mass index in patients with bipolar disorder. Chronobiol. Int. 30, 577–582 (2013).

Hillman, R. W. & Conway, H. C. Season of birth and relative body weight. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 25, 279–281 (1972).

Henneberg, M. & Louw, G. J. Further studies on the month-of-birth effect on body size: rural schoolchildren and an animal model. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 91, 235–244 (1993).

Brabec, M. et al. Birth seasons and heights among girls and boys below 12 years of age: lasting effects and catch-up growth among native Amazonians in Bolivia. Ann. Hum. Biol. 45, 299–313 (2018).

Kościński, K., Krenz-Niedbała, M. & Kozłowska-Rajewicz, A. Month-of-birth effect on height and weight in Polish rural children. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 16, 31–42 (2004).

Fitt, A. B. The heights and weights of men according to month of birth. Hum. Biol. 27, 138–142 (1955).

Mehrang, S., Helander, E., Chieh, A. & Korhonen. I. Seasonal weight variation patterns in seven countries located in northern and southern hemispheres. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2475–2478 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28268826 (2016).

Kramer, R. S. S. No effect of birth month or season on height in a large international sample of adults. Anthropol. Rev. 79, 211–215 (2016).

Sohn, K. The influence of birth season on height: evidence from Indonesia. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 157, 659–665 (2015).

Rosset, I., Żądzińska, E., Strapagiel, D., Grzelak, A. & Henneberg, M. Association between body height and month of birth among women of European origin in northern and southern hemispheres. Am. J. Hum. Biol. e22967 (2017).

Krenz-Niedbała, M., Puch, A. & Kościński, K. Season of birth and subsequent body size: the potential role of prenatal vitamin D. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 23, 190–200 (2011).

Puch, E. A., Krenz-Niedbała, M. & Chrzanowska, M. Body height differentiation by season of birth: girls from Cracow, Poland. Anthropol. Rev. 71, 3–16 (2008).

Schreier, N., Moltchanova, E., Forsén, T., Kajantie, E. & Eriksson, J. G. Seasonality and ambient temperature at time of conception in term-born individuals—influences on cardiovascular disease and obesity in adult life. Int. J. Circumpol. Health 72, 21466 (2013).

Levitan, R. D. et al. A birth-season/DRD4 gene interaction predicts weight gain and obesity in women with seasonal affective disorder: a seasonal thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology 31, 2498–2503 (2006).

Jacobsen, R. et al. The influence of early exposure to vitamin D for development of diseases later in life. BMC Public Health 13, 515 (2013).

Thorne‐Lyman, A. & Fawzi, W. W. Vitamin D during pregnancy and maternal, neonatal and infant health outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 26, 75–90 (2012).

Strand, L. B., Barnett, A. G. & Tong, S. The influence of season and ambient temperature on birth outcomes: a review of the epidemiological literature. Environ. Res. 111, 451–462 (2011).

Wolf, J. & Armstrong, B. The association of season and temperature with adverse pregnancy outcome in two German states, a time-series analysis. PLoS ONE 7, e40228 (2012).

Poursafa, P., Keikha, M. & Kelishadi, R. Systematic review on adverse birth outcomes of climate change. J. Res. Med. Sci. 20, 397–402 (2015).

Poursafa, P. et al. A systematic review on the effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on cardiometabolic impairment. Int. J. Prev. Med. 8, 19 (2017).

Zarean, M., Poursafa, P., Amin, M. M. & Kelishadi, R. Association of endocrine disrupting chemicals, bisphenol A and phthalates, with childhood obesity: a systematic review. J. Pediatr. Rev. e11894 (2017).

An, R. & Xiang, X. Age-period-cohort analyses of obesity prevalence in US adults. Public Health 141, 163–169 (2016).

Murphy, C. C., Yang, Y. C., Shaheen, N. J., Hofstetter, W. L. & Sandler, R. S. An age-period-cohort analysis of obesity and incident esophageal adenocarcinoma among white males. Dis. Esophagus 30, 1–8 (2017).

Bell, A. & Jones, K. Don’t birth cohorts matter? A commentary and simulation exercise on Reither, Hauser, and Yang’s (2009) age-period-cohort study of obesity. Soc. Sci. Med. 101, 176–180 (2014).

Reither, E. N., Hauser, R. M. & Yang, Y. Do birth cohorts matter? Age-period-cohort analyses of the obesity epidemic in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 69, 1439–48. (2009).

Kwon, J. W. et al. Effects of age, time period, and birth cohort on the prevalence of diabetes and obesity in Korean men. Diabetes Care 31, 255–260 (2008).

Allman-Farinelli, M. A., Chey, T., Bauman, A. E., Gill, T. & James, W. P. Age, period and birth cohort effects on prevalence of overweight and obesity in Australian adults from 1990 to 2000. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 62, 898–8907 (2008).

Chmielewski, P. & Borysławski, K. Understanding the links between month of birth, body height, and longevity: Why some studies reveal that shorter people live longer—further evidence of seasonal programming from the Polish population. Anthropol. Rev. 79, 375–95. (2016).

Pomeroy, E. et al. Birth month associations with height, head circumference, and limb lengths among peruvian children. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 154, 115–124 (2014).

Zhang, W. Month of birth, socioeconomic background and height in rural Chinese men. J. Biosoc. Sci. 43, 641–656 (2011).

Schwekendiek, D. & Pak, S. Recent growth of children in the two Koreas: a meta-analysis. Econ. Hum. Biol. 7, 109–112 (2009).

Banegas, J. R., Rodríguez-Artalejo, F., Graciani, A., Cruz, J. Jdl & Gutiérrez-Fisac, J. L. Month of birth and height of Spanish middle-aged men. Ann. Hum. Biol. 28, 15–20 (2001).

Pollitt, E. & Arthur, J. Seasonality and weight gain during the first year of life. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 1, 747–56 (1989).

Pagezy, H. & Hauspie, R. C. Seasonal variation in the growth rate of weight in African babies, aged 0 to 4 years. Ecol. Food Nutr. 18, 29–41 (1985).

Wu, L., Ding, Y., Rui, X. L. & Mao, C. P. Seasonal variations in birth weight in Suzhou Industrial Park. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 29, 758–61 (2016).

Bahrami, N., Soleimani, M. A., Chan, Y. H. & Masoudi, R. Study of some determinants of birth weight in Qazvin. J. Clin. Nurs. Midwife. 3, 56–64 (2015).

Jensen, C. B. et al. Secular trends in seasonal variation in birth weight. Early Hum. Dev. 91, 361–365 (2015).

Torche, F. & Corvalan, A. Seasonality of birth weight in Chile: environmental and socioeconomic factors. Ann. Epidemiol. 20, 818–26. (2010).

Chodick, G., Flash, S., Deoitch, Y. & Shalev, V. Seasonality in birth weight: review of global patterns and potential causes. Hum. Biol. 81, 463–477 (2009).

Elter, K., Ay, E., Uyar, E. & Kavak, Z. N. Exposure to low outdoor temperature in the midtrimester is associated with low birth weight. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 44, 553–557 (2004).

Murray, L. J. et al. Season and outdoor ambient temperature: effects on birth weight. Obstet. Gynecol. 96(5 Pt 1), 689–695 (2000).

Gloria-Bottinia, F. et al. Rh system and intrauterine growth. Interaction with season of birth. Dis. Markers 16, 139–142 (2000).

Waldie, K. E., Poulton, R., Kirk, I. J. & Silva, P. A. The effects of pre- and post-natal sunlight exposure on human growth: evidence from the Southern Hemisphere. Early Hum. Dev. 60, 35–42 (2000).

Yang, M. & Leung, S. S. F. Weight and length growth of two Chinese infant groups and the seasonal effects on their growth. Ann. Hum. Biol. 21, 547–562 (2009).

Matsuda, S., Sone, T., Doi, T. & Kahyo, H. Seasonality of mean birth weight and mean gestational period in Japan. Hum. Biol. 65, 481–501 (1993).

Adair, L. S. & Pollitt, E. Seasonal variation in pre- and postpartum maternal body measurement and infant birthweights. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 62, 325–31 (1983).

Bantje, H. Seasonal variations in birthweight distribution in Ikwiriri village, Tanzania. J. Trop. Pediatr. 29, 50–54 (1983).

Roberts, S. B., Paul, A. A., Cole, T. J. & Whitehead, R. G. Seasonal changes in activity, birth weight and lactational performance in rural Gambian women. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 76, 668–678 (1982).

Selvin, S. & Janerich, D. T. Four factors influencing birth weight. Br. J. Prev. Soc. Med. 25, 12–16 (1971).

Salber, E. J. & Badshaw, E. S. Birth weights of South African babies. III. Seasonal variation in birth weight. Br. J. Soc. Med. 6, 190–191 (1952).

Li, T.-a Seasonal variation of the birth weight of the newborn. J. Pediatr. 8, 459–69 (1936).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H., R.K., and M.K.: substantial contribution to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data. Z.H., M.K., R.R., S.S.D., and M.G.: drafting the paper or revising it critically for important intellectual content. Z.H., R.K., and M.K.: final approval of the version to be submitted. All authors contributed in making revisions, approved the final draft, and accepted the responsibility of the paper content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hemati, Z., Keikha, M., Riahi, R. et al. A systematic review on the association of month and season of birth with future anthropometric measures. Pediatr Res 89, 31–45 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-0908-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-0908-4

This article is cited by

-

Placental transcriptomic signatures of prenatal and preconceptional maternal stress

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

-

Seasonality and Sex-Biased Fluctuation of Birth Weight in Tibetan Populations

Phenomics (2022)