Abstract

No prior studies have evaluated the efficacy and safety of zolpidem and zopiclone to treat insomnia of demented patients. This randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial used these drugs to treat patients with probable, late onset Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) (DSM V and NINCDS-ADRDA criteria) exhibiting insomnia (DSM V criteria and nocturnal NPI scores ≥ 2). Actigraphic records were performed for 7 days at baseline and for 14 days during the treatment period in 62 patients aged 80.5 years in average and randomized at a 1:1:1 ratio for administration of zolpidem 10 mg/day, zopiclone 7.5 mg/day or placebo. Primary endpoint was the main nocturnal sleep duration (MNSD), whereas secondary outcomes were the proportion of the night time slept, awake time after sleep onset (WASO), nocturnal awakenings, total daytime sleep time and daytime naps. Cognitive and functional domains were tested before and after drug/placebo use. Three participants under zopiclone use had intervention interrupted due to intense daytime sedation and worsened agitation with wandering. Zopiclone produced an 81 min increase in MNSD (95% confidence interval (CI): −0.8, 163.2), a 26 min reduction in WASO (95% CI: −56.2, 4.8) and a 2-episode decrease in awakening per night (95% CI: −4.0, 0.4) in average compared to placebo. Zolpidem yielded no significant difference in MNSD despite a significant 22 min reduction in WASO (95% CI: −52.5, 8.3) and a reduction of 1 awakening each night (95% CI: −3.4, 1.2) in relation to placebo. There was a 1-point reduction in mean performance in the symbols search test among zolpidem users (95% CI: −4.1, 1.5) and an almost eight-point reduction in average scores in the digit-symbol coding test among zopiclone users (95% CI: −21.7, 6.2). In summary, short-term use of zolpidem or zopiclone by older insomniacs with AD appears to be clinically helpful, even though safety and tolerance remain issues to be personalized in healthcare settings and further investigated in subsequent trials. This trial was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03075241.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, there are over 50 million people worldwide living with dementia in 2020, and 152 million are expected to carry the disease in 2050 [1, 2]. Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) accounts for to 60–70% of the cases, being characterized as a degenerative process of the central nervous system (CNS) that impairs memory, thinking, language, and executive functions [3]. Also, the circadian pacemaker located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (important for maintaining sleep) is believed to be dysregulated in AD patients [4]. Approximately half of the AD patients develop sleep disorders [5] at some stage of the disease, with insomnia diagnosed in up to 45% of cases [6]. Although the etiology of sleep disorders is complex and multifactorial, aspects such as brain tissue loss, the patient’s environment, medications taken by the patient, and dementia-related behavioral symptoms may be involved in this process, triggering changes in the sleep-wake cycle and circadian rhythm [7].

Insomnia in patients with AD is often associated with difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, sleep fragmentation, nocturnal agitation with wandering, and daytime sleepiness, which significantly impair the patient’s quality of life and increase the risk of falls, thus increasing the burden on caregivers and family members as well as the likelihood of patient institutionalization [8, 9].

Insomnia worsens as dementia progresses [10] and is more frequent in moderate and severe stages of the neurodegeneration in the CNS, making any approach challenging for physicians as no medication has been approved for this purpose [11]. Even though a personalized and comprehensive evaluation of each patient is mandatory, nonpharmacological treatments are usually the standard first-line intervention for chronic insomnia [12]. Sleep hygiene, cognitive therapy, sensory stimulation and relaxation training are common strategies to improve sleep quality in AD patients [13, 14]. So far, the effectiveness of nonpharmacological strategies range from conclusive (for light therapy, for instance) to inconclusive (for most other interventions), and with multi-modal programs being the most promising avenue, but at a higher cost in expenses, effort and time for patients, family and/or caregivers [15]. Therefore, pharmacological treatment prevails as main approach when results are expected in the short-term, especially in view of the significant family burden in caring for severely disabled patients. Some drugs acting on the CNS, such as antidepressants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, antihistamines, melatonin and orexin receptor agonists have been used off-label despite limited empirical evidence on the efficacy and safety of their long-term use in patients with AD [16, 17].

The so-called “Z-drugs” (zolpidem, zopiclone, eszopiclone, and zaleplone) are nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics commonly prescribed for the treatment of insomnia due to presumed tolerability, efficacy, and safety demonstrated in studies with non-demented older adults [18, 19]. Zolpidem is currently the most frequently prescribed hypnotic in the United States, with 5 million users nationwide [20] (35% between 65 and 85 years old [21]). With high affinity for γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) α1 subunit and low affinity for α2 and α3 subunits (and negligible binding to α5 subunit), zolpidem displays strong hypnotic properties without significant anxiolytic, myorelaxant, or anticonvulsant effects [22]. Zopiclone, another widely used hypnotic, also increases neuronal inhibition as agonist of GABAA receptor [23], while bearing mild anticonvulsant and muscle relaxant effects, with anxiolytic and hypnotic properties comparable to those of conventional benzodiazepines [24]. Unlike zolpidem, zopiclone has less specificity for binding sites [25]. However, both zolpidem and zopiclone have shorter half-lives (~2 and 3.5 h in young adults, respectively) compared to most benzodiazepines and other sleep-promoting agents, what might favor a decrease in incidence of residual, next-morning effects on cognitive and psychomotor performance [26].

Few studies have evaluated the efficacy of drugs in the treatment of insomnia of patients with AD. Trazodone appears to increase total sleep time by about 40 min in these patients, and also to reduce the number of night time awakenings [27]. According to the latest Cochrane review on pharmacotherapy for sleep disorders in patients with dementia, there is a clear lack of evidence to guide drug treatment of sleep problems in dementia, mainly due to the lack of randomized controlled trials [28]. Therefore, the area needs pragmatic trials, particularly on drugs commonly used in clinical settings.

Our primary objective was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of zolpidem 10 mg and zopiclone 7.5 mg vs placebo in the treatment of insomnia in patients with probable AD, with sleep outcomes measured by actigraphy and structured questionnaires.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a randomized, triple-blind (patients, clinical raters, and data analyzers), placebo-controlled trial with actigraphic sleep data recorded continuously for 7-days at baseline and then for a subsequent 14-days period under administration of zolpidem 10 mg/day, zopiclone 7.5 mg/day, or placebo in patients with probable AD and insomnia treated at a 1:1:1 ratio.

The study was conducted at a single center (Multidisciplinary Geriatric Center at the Brasília University Hospital, Brazil) between October 2016 and April 2020, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and European Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. The trial was approved by the institution’s Ethics Committee (number 002262/2016), is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (number NCT03075241) and followed CONSORT recommendations (Supplemental material 1). Written informed consent was obtained from each formal caregiver and/or legal representative.

Screening and eligibility criteria for participants

Eligible participants were all community-dwelling individuals of both sexes, aged ≥65 years (range of 65–95 years old) with a diagnosis of major neurocognitive disorder (according to DSM-V criteria) [29] and probable late-onset AD (according to NINCDS-ADRDA criteria) [30], accompanied by clinical features compatible with insomnia disorder according to the DSM-V [29] and the neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI) [31] on night time behavior disorders (frequency and severity ≥ 2). Additional eligibility criteria included a mini-mental state examination (MMSE) score of 0–24 [32], Hachinski ischemic score ≤ 4 [33], Cornell scale score < 6 [34], stable medication use for at least 4 weeks with no benzodiazepine intake in 12 weeks before or during the study, and absence of lacunar infarction in a strategic cortical area (evidenced by computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging) or clinical events suggestive of stroke or other intracranial disease. Only patients with a caregiver or family member able to provide informed consent, to accompany the patient during the prespecified study period, and to place and operate an actigraph on an upper limb were selected.

Patients were excluded if they had sleep disorders associated with an acute illness, delirium, or psychiatric illness and if they had clinically significant movement disorders or upper limb paralysis that could preclude actigraphic assessment. Patients with a history of clinically important or unstable medical conditions and those with major psychiatric disorders judged by the investigators as likely to preclude completion of the study were also excluded. Finally, patients with a history or reluctant to maintain caffeine abstinence after 2 pm, with an alcohol intake > 2 doses per day or > 1 dose after 6 pm during the study period, with dysphagia preventing oral medication/placebo intake, and/or with severe agitation were excluded. Patients could not have participated in another trial of an investigational medication within 6 months prior to screening. Use of antipsychotics and antidepressants with sedative properties was allowed if prescribed at least 30 days prior to the screening visit and remained stable during screening, baseline assessment, and intervention.

Procedures

This study included successive periods and procedures that consisted of screening patients for admission to the study, baseline assessments and treatment (intervention) with zolpidem 10 mg, zopiclone 7.5 mg, or placebo, followed by another round of assessments. Each screened patient admitted to the study was subjected to a baseline, standard protocol of physical examination by means of vital signs, brief neurological assessment, and placement of the actigraph on the dominant wrist for a 7-day recording period. The actigraphic data for each participant were extracted after this baseline period and analyzed for sleep quality and sleep-related variables, with inclusion and exclusion criteria reviewed at this time. A comprehensive evaluation of major cognitive domains as attention, memory, speed, flexibility and executive function was performed by means of a set of neuropsychological instruments as follows: forward and backward digit span [35], WAIS-III digit symbol-coding and symbol search subtests [36], trail making test A and B [37], verbal fluency test [38], Katz index [39], Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR) [40, 41], Cornell scale [34] and neuropsychological inventory—sleep and behavior disorder item [42]. To rule out the possibility of sleep misperception by the caregiver or patient, eligibility for intervention took into account the following actigraphic criteria: nocturnal total sleep time (NTST) < 7 h per night and/or > 3 night time awakenings.

About 1 week after completing the baseline assessment, each patient had an actigraph placed again in the dominant arm and caregivers were given a randomized bottle, masked by using an alphanumeric code, containing capsules. Each caregiver was instructed to administer a single capsule to the patient until 9 pm and put the patient to bed immediately after that, for a period of 14 days. Actigraphic data were recorded for 2 weeks. At admission, any continued use of CNS-acting drugs was recorded and deemed as an AD-associated (memantine and anticholinesterase inhibitors), antidepressant, antipsychotic, or other hypnotic drug according to the ATC system. Throughout the study period, patients were instructed not to change long-term medications, to avoid drinking xanthine-rich beverages after 2 pm, and to limit alcohol intake to a maximum of 2 doses per day, with only 1 dose allowed after 6 pm. After the intervention period (14 days), the actigraphic data were extracted, and the same scales and cognitive tests used for baseline assessment were reapplied.

Apparatus

ActTrust® AT0503 actigraphs (Condor Instruments©) were used for assessment, and the actigraphic data were analyzed with ActStudio® software (version 1.0.5.3). The algorithm developed by Cole et al. [43] was used to estimate the duration of sleep and wakefulness, with the beginning of each phase defined as an interval of 10 immobile minutes for sleep onset and 10 min of agitation for sleep end (sleep interval detection algorithm). Actigraphic analysis is a method recommended for use in studies of hypnotic drugs in patients with dementia [44].

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the main nocturnal sleep duration (MNSD), which corresponds to the longest sleep period starting after 8 pm. Secondary outcomes included the following: (i) night time waking after sleep onset (WASO); (ii) number of awakenings during nocturnal sleep, that is, after sleep onset and before the final awakening in the morning; (iii) daytime total sleep time (DTST), within the continuous 12 h period from 8 am to 8 pm; and (iv) number of daytime naps (NAPS), defined as a daytime sleep period > 10 min.

Other outcomes included the following: (i) changes in cognitive scores (MMSE, forward and backward digit span, WAIS-III digit symbol-coding and symbol search subtests, trail making test A and B, and verbal fluency test); (ii) functional status (Katz index); and (iii) subjective perception of effectiveness (subitem of the NPI assessing the caregiver’s perception of insomnia severity and frequency after treatment). Finally, caregivers were asked to answer on a five-point Likert scale the following question: “With the use of the medication, how is the patient sleeping? Same, better, much better, worse, or much worse?”.

Tolerability and adherence assessments

After the intervention, physical and neurological examinations that included measurement of systemic blood pressure, heart rate, signs of sedation, and damage to the main reflexes were performed. Pre- and post-treatment changes in the results were recorded. Occurrence of adverse events was openly questioned by the attending physician as part of the study closure, being initially self-reported by patients and/or caregivers and then complemented by a semi-guided clinical survey to unveil episodes encompassing dizziness, falls, dry mouth, daytime sleepiness, mental confusion, motor deficits, and gastrointestinal and urinary symptoms. Adverse events were classified as mild, moderate, severe, or death according to the World Health Organization’s International Classification for Patient Safety [45].

Adherence was assessed by a manual capsule count. The number of capsules was used to calculate the percentage or rate of adherence, which was considered adequate if capsule intake was ≥85% [46].

Randomization and masking

The medications were prepared by the teaching compounding pharmacy at the University of Brasília using a physical masking method. Intact zolpidem 10 mg (Stilnox®) and zopiclone 7.5 mg (Imovane®) tablets, both commercially obtained from the reference manufacturer in Brazil (Sanofi-Aventis©), were introduced in size 0 blue hard gelatin capsules, and the excess volume was filled with lactose as excipient. Placebo capsules, identical in appearance to those containing zolpidem or zopiclone tablets, were filled with of following proportions excipients: microcrystalline cellulose 35%, sodium starch glycolate 3%, hypromellose 3.5%, magnesium stearate 0.5%, colloidal silicon dioxide 5%, and lactose monohydrate qsp 100% [47, 48].

Of 96 patients screened for eligibility, 34 were ruled out based on exclusion criteria (as in Supplemental material 2) and 62 were randomly allocated to three groups, as follows: zolpidem 10 mg (n = 21), zopiclone 7.5 mg (n = 21), and placebo (n = 20). The allocation sequence was computer-generated using a randomized block design based on three-digit alphanumeric strings created with the True Random Number Service (Dublin, Ireland; available at www.random.org/strings). A pharmacist not directly involved in the care provided to patients was responsible for labeling and handing the numbered bottles containing 15 capsules each and for keeping the allocation sequence concealed until interventions were assigned and data prepared for statistical analysis. The retrieval, reading and analysis of data obtained by actigraphy were performed by independent personnel without contact with patients or the randomization process.

Statistical analysis

Baseline measurements of each intervention group were compared to placebo using the chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test in case of expected frequency < 1) for categorical variables. The t-test was used for continuous variables with normal distribution and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for discrete non-Gaussian distributed variables.

A general linear model for analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to compare variations of parameters from baseline (delta) between the groups treated and not treated with zolpidem or zopiclone. Variation scores were considered dependent variables, whereas treatment type was the independent variable. The baseline values of each variable were covariates in the model. The values of the absolute mean change for each arm were added to indicate the net difference between the treatment arms. The null hypothesis was rejected in each statistical test when p was < 0.05. Effect sizes were calculated and categorized according to Cohen’s criteria [49]. All analyses were performed using RStudio Team, version 2015.

Results

Patient characteristics and baseline measurements

Patients’ baseline characteristics were similar in the three treatment arms, except for a slightly higher educational level among zopiclone users (Table 1). The overall mean age was of 80.5 years, and most participants (50.8%) had 4 or more years of schooling, were widowed (59.3%), and had moderate to severe AD (83.0%). There was no statistically significant difference in actigraphic measures of sleep between the groups. Noteworthy, no participants enrolled for intervention declared alcohol drinking during the study and all denied history of alcohol abuse, as self-reported and/or informed by caregiver.

All three groups were also similar in cognitive and functional status at baseline, with mean scores indicating individuals partially dependent in activities of daily living (mean Katz index, 4.3) and with evident signs of impairment in functions such as short-term memory and working memory (mean digit span score, 4.4). The average performance in complex visual screening tests associated with executive function (score of 21.7 and 25.3 in trail making test A and B, respectively) and in executive function combined with semantic memory and language (verbal fluency test score, 4.6) also indicated low cognitive ability at baseline.

Treatment adherence and safety monitoring

Participants who completed the study showed a reasonable adherence rate (85% or more) to the protocol. Capsule count indicated that six patients (four treated with zolpidem and two with zopiclone) missed one dose of medication, whereas three patients (two treated with zolpidem and one with zopiclone) missed two doses within the 14-day intervention period. No participant dropped out of the study due to treatment intolerance in the zolpidem and placebo groups. However, three patients in the zopiclone group discontinued intervention due to severe daytime sedation (n = 2; 1♂ and 1♀) and worsened agitation with wandering (n = 1; ♀), all in CDR 3 stage and not using memantine, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or other psychoactive drugs. Adverse events occurred in three patients receiving zolpidem, all of mild intensity: one due to agitation and hallucination up to 3 h after medication intake, one due to mental confusion associated with wandering, and one due to morning sleepiness resulting in same height fall. These events did not impair participation in the study. One patient (♀) in the zopiclone group had mild morning sleepiness. There were no reports of adverse events in the placebo group.

Efficacy results on sleep

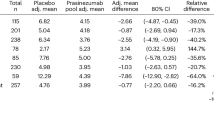

ANCOVA revealed that, compared to placebo, patients treated with zopiclone had an increase of 81 min in MNSD (95% confidence interval (CI): −0.8, 163.2; p = 0.043), a reduction of about 26 min in WASO (95% CI: −56.2, 4.8; p = 0.014), and a decrease of about two awakening episodes per night (95% CI: −4.0, 0.4; p < 0.001). Compared to placebo, patients receiving zolpidem showed no statistically significant difference in MNSD (p = 0.802) despite having a significant reduction of 22 min in WASO (95% CI: −52.5, 8.3; p = 0.029) and a mean reduction of one episode of awakening per night (95% CI: −3.4, 1.2; p < 0.001). It should be noted that placebo had no effect on any of the sleep-related outcomes (Tables 2 and 3).

Furthermore, ANCOVA results showed no significant effect on daytime sleepiness or other sleep-related outcomes. A subjective assessment according to NPI scores showed no effect of zolpidem on sleep. Nonetheless, patients treated with zopiclone had a significant two-point greater decrease in the scale (95% CI: −4.0, −0.2; p = 0.014) compared to placebo, reducing frequency and intensity of insomnia symptoms. Regarding caregivers’ overall perception of treatment efficacy, there was a significant improvement in sleep quality with the use of zopiclone, where 88.9% of caregivers reported that the patient was sleeping better or much better in relation to their pre-treatment status (p = 0.002). Such finding was not reported with zolpidem (p = 0.085).

Function and cognition outcomes

As shown in Tables 4 and 5, there was a significantly reduced performance in the symbol search test (−1.3 in the score; 95% CI: −4.1, 1.5; p = 0.025) in patients treated with zolpidem and in the symbol-coding test (−7.7 in the score; 95% CI: −21.7, 6.2; p = 0.001) in those treated with zopiclone. There was no impact on functional status with any of the medications.

Discussion

In this triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial, we investigated the efficacy and safety of zolpidem and zopiclone in the treatment of insomnia in older adults with late onset AD, using the highest daily dose for immediate-release of each drug as available in the Brazilian market (10 mg and 7.5 mg, respectively). Zopiclone 7.5 mg produced a significant improvement in the primary outcome (81 min increase in MNSD), as well as a reduction in WASO and night time awakenings. Although zolpidem 10 mg produced no benefit in the primary outcome, it improved WASO and night time awakenings after 14 days of intervention. Both medications impaired patients’ cognitive performance, as measured by specific tests (digit symbol-coding and symbol search), but without significant impact on functional status.

Insomnia in patients with AD remains a challenge in clinical practice. Data from the latest Cochrane systematic review [50] shows that trazodone 50 mg increased NTST by 42 min and sleep efficiency by 8% compared to placebo in patients with AD [27]. Mirtazapine, however, provided no sleep benefit for AD patients [51]. The use of the orexin receptor antagonist suvorexant (10–20 mg) in cases of probable AD with insomnia increased total sleep time by 28 min and sleep efficiency by 6%, while decreased WASO by 16 min after 4 weeks of treatment [52].

To our knowledge, no other study evaluated the use of zolpidem or zopiclone in the routine management of insomnia in this group of patients. In non-dementia settings, Mouret et al. [53] reported a gain in NTST of 122 min compared to baseline sleep, while Hemmerter et al. [54] found an increase of 32 min in sleep duration with a reduction of five night time awakenings compared to placebo. Leufkens et al. [55] also obtained satisfactory results in NTST (gain of 28 min), WASO (reduction of 25 min), and sleep efficiency (increase of 7%) with the use of a single oral dose of zopiclone 7.5 mg compared to placebo in older insomniac patients who used hypnotics infrequently. In the present trial, the gain in MNSD with the use of zopiclone was much higher than that reported with the use of trazodone [27], suvorexant [52], and mirtazapine [51]. The superior benefits of zopiclone for night time sleep may be explained by its non-selective affinity for benzodiazepine receptors (α1, α2, α3, and α5 subunits) [25]. Based on this, finding a greater proportion of adverse effects with this drug does not surprise. Furthermore, the half-life of zopiclone is longer in older adults (≈8 h) than in healthy young adults (3.5–6.5 h) due to reduced hepatic metabolism with senescence [56]. Therefore, age may have potentiated the effects of zopiclone (in relation to zolpidem) on sleep and other outcomes.

In a similar vein, the lack of a significant gain in MNSD with zolpidem (despite benefits observed in WASO and night time awakenings) could also be explained by the characteristics of the formulation used in the trial (immediate-release), which has a half-life of 1.5–2.4 h [57]. This formulation was chosen on grounds of the lower rates of oral drug clearance [58] and biotransformation in older adults (especially women) [59], who achieve zolpidem serum concentrations up to 50% higher than young adults, with potential to modify the overall sleep profile. It remains necessary to investigate whether a prolonged-release formulation would produce more pronounced and safer effects than those observed herein. Zolpidem is also known to have a tenfold higher affinity for the benzodiazepine receptor α1 subunit than for α2 and/or α3 subunits, with an almost negligible affinity for the α5 subunit [60, 61]. Changes associated with aging and/or the AD neuropathology in the expression and/or function of GABAA receptor subunits, either in the whole brain or in specific brain regions [62, 63], may also explain the lower response promoted by zolpidem in the study population.

Mild adverse events related to behavior, cognition, and next-morning residual effects were reported in the zolpidem and zopiclone groups, which is consistent with data reported for their use in older adults [64, 65]. The intervention had to be discontinued in three patients in the zopiclone group (14%) due to important adverse events (daytime sedation and worsening agitation with wandering). Interestingly, all occurred in non-users of other psychoactive agents. If adverse effects of zopiclone can be compensated by other CNS-acting drugs remains to be determined. No dropouts occurred among patients receiving zolpidem. There was also a significant drop in performance in the digit symbol-coding (zopiclone) and in the symbol search (zolpidem) tests, where executive functions (processing speed and sustained attention) and working memory are assessed, this negative effect is not expected to have real clinical impact on instrumental daily living activities (handling finances, driving, and shopping, among others) of already impaired patients with moderate to severe AD. At this stage, benefits as a bettered quality of life and reduced caregiver burden from an improved sleep pattern tend to be more valuable from a clinical standpoint. Similar findings have already been reported in older adults using zopiclone 3.75 mg and zolpidem 5 mg [66, 67], in whom increased body sway and impaired memory were observed. However, in a recent systematic review, assessments on older adults using zolpidem during night time and/or next-morning awakening pointed to minimal or no losses in psychometric and/or psychomotor performance [68]. Likewise, the literature also presents evidence that cognitive and psychomotor functions as well as alertness on waking do not appear to be substantially impacted by the use of zopiclone [54, 69,70,71]. Despite of (or owing to) the controversy, zopiclone and zolpidem present pharmacological issues regarding tolerability and safety that cannot be neglected and deserve further investigation, being so far comparable in frequency and intensity to those of BZDs as evidenced by studies elsewhere [72,73,74], and with use of all these drug classes intended to be personalized, implemented with caution, and under watchful surveillance.

In the present study, subjective sleep assessments were consistent with actigraphic measures by indicating improvements in overall sleep quality perceived by caregivers among patients treated with zopiclone (χ2 = 12.78, df = 2, p = 0.002), but not with zolpidem (p = 0.085, Fisher’s exact test), occurring concomitantly with a reduction in the frequency/severity of insomnia symptoms and caregiver burden. Placebo was designed to be ineffective, which was confirmed by the lack of observable therapeutic effects according to objective measures. Nevertheless, a portion of the caregivers (35%) reported that placebo-treated patients were sleeping better or much better, which may be attributable to benefits resulting from the symbolic participation in the trial, its rituals, and/or expectations/hopes about a treatment [75,76,77], but also to caregiver misperception of the outcomes.

Despite adjustments for multiple potential confounding factors, our study has some limitations. Because polysomnography is unfeasible in the context of moderate/severe forms of AD (and most cases herein were as so), the possibility of undiagnosed primary sleep disorders (as parasomnias) cannot be excluded. Sleep latency was not measured due to poorly completed sleep diaries as well as to technical restraints in the actigraphy devices used, being a model devoid of an ambient light sensor. Regarding adverse events, underreporting due to difficulties in recognizing or in reporting may have occurred, and analyses on enhancement or attenuation of events by concomitant use of other drugs was precluded by sample shortage. Also, the trial did not include assessments on serum drug levels to assist in the interpretation of adverse events. Some strengths should also be noted, such as the clinical accuracy in the diagnosis of AD among the recruited sample, coupled subjective-objective diagnosis of insomnia, the triple-blind design, the high adherence of the participants, and the consistency across results obtained by complementary means, with no conflicting results. In summary, our data supports that short-term use of zolpidem or zopiclone by older insomniacs with AD can be clinically helpful, even though safety and tolerance remain issues to be personalized in healthcare settings and further investigated in subsequent trials.

Both zopiclone and zolpidem reduced time spent awake during the night and the number of awakenings after sleep onset, but only zopiclone significantly increased the duration of the main sleep time at night, thus improving the sleep pattern. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine states that goals of insomnia treatment are to improve the quality and/or time (> 6 h) of nocturnal sleep, to eliminate daytime impairments from insomnia, to reduce the frequency and duration of night time awakenings, and to reduce sleep latency [78]. At least partially, our study demonstrated the effectiveness of zopiclone and zolpidem in promoting sleep improvement in a sample of older adults with a wide range of AD stages, and in ways that reflect the expected pharmacokinetic profile of each medication. This study does not end the discussion about the applicability of the main Z-drugs in the treatment of insomnia in AD patients. Future studies should explore the efficacy and safety in each clinical stage, also consider longer intervention periods and address both short- as well as long-term effects on sleep as well as on cognitive and functional statuses in AD patients.

References

Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia facts & figures. 2021. https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia-facts-figures/. Accessed 14 June 2021.

Nichols E, Szoeke CEI, Vollset SE, Abbasi N, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:88–106.

Alzheimer Association. 2018 Alzheimer’ s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14:367–429.

Vitiello MV, Borson S. Sleep Disturbances in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:777–96.

Burke SL, Hu T, Spadola CE, Burgess A, Li T, Cadet T. Treatment of Sleep Disturbance May Reduce the Risk of Future Probable Alzheimer’ s Disease. J Aging Health. 2018;31:322–42.

Guarnieri B, Adorni F, Musicco M, Appollonio I, Bonanni E, Caffarra P, et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in mild cognitive impairment and dementing disorders: a multicenter Italian clinical cross-sectional study on 431 patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;33:50–8.

Deschenes CL, McCurry SM. Current treatments for sleep disturbances in individuals with dementia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11:20–6.

Mccurry SM, Ancoli-israel S. Sleep Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2003;5:261–72.

Most EIS, Aboudan S, Scheltens P, Van Someren EJW. Discrepancy Between Subjective and Objective Sleep Disturbances in Early- and Moderate-Stage Alzheimer Disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:460–7.

Bliwise DL, Hughes M, Mcmahon PM, Kutner N. Observed Sleep/Wakefulness and Severity of Dementia in an Alzheimer’s Disease Special Care Unit. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50:303–6.

Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390:2673–734.

Urrestarazu E, Iriarte J. Clinical management of sleep disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease: current and emerging strategies. Nat Sci Sleep. 2016;8:21–33.

O’Neil ME, Freeman M, Christensen V, Telerant R, Addleman A, Kansagara D. A Systematic Evidence Review of Non-pharmacological Interventions for Behavioral Symptoms of Dementia. Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington (DC); 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK54971/.

Wilfling D, Junghans A, Marshall L, Eisemann N, Meyer G, Möhler R, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for sleep disturbances in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015. September 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011881.

O’Caoimh R, Mannion H, Sezgin D, O’Donovan MR, Liew A, Molloy DW. Non-pharmacological treatments for sleep disturbance in mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2019;127:82–94.

Verdelho A, Bentes C. Insomnia in dementia: a practical approach. In: Verdelho A, Gonçalves-Pereira M, editors. Neuropsychiatr. Symptoms Cogn. Impair. Dement., Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017.

Abad VC, Guilleminault C. Insomnia in elderly patients: recommendations for pharmacological management. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:791–817.

Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, Bjorvatn B, Dolenc Groselj L, Ellis JG, et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2017;26:675–700.

Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:487–504.

Greenblatt DJ, Roth T. Zolpidem for insomnia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13:879–93.

Moore TJ, Mattison DR. Assessment of Patterns of Potentially Unsafe Use of Zolpidem. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1275.

Salva P, Costa J. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Zolpidem Therapeutic Implications. J Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;29:142–53.

Atkin T, Comai S, Gobbi G. Drugs for Insomnia beyond Benzodiazepines: pharmacology, clinical applications, and discovery. Pharm Rev. 2018;70:197–245.

Julou L, Bardone MC, Blanchard JC, Garret C, Stutzmann JM. Pharmacological Studies on Zopiclone. Pharmacology. 1983;27:46–58.

Doble A, Canton T, Malgouris C, Stutzmann J, Piot O, Bardone M, et al. The mechanism of action of zopiclone. Eur Psychiatry. 1995;10:117s–128s.

Drover APDR. Comparative Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Short-Acting Hypnosedatives. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:227–38.

Camargos EF, Louzada LL, Quintas JL, Naves JOS, Louzada FM, Nóbrega OT. Trazodone improves sleep parameters in Alzheimer disease patients: a randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:1565–74.

McCleery J, Sharpley AL. Pharmacotherapies for sleep disturbances in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020. November 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009178.pub4.

American Psychiatric Association A. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, c2013.; 2013.

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group* under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–939.

Cummings JL. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology. 1997;48:10S–16S.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical state method for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98.

Rosen WG, Terry RD, Fuld PA, Katzman R, Peck A. Pathological verification of ischemic score in differentiation of dementias. Ann Neurol. 1980;7:486–8.

Alexopoulos G, Abrams R, Young R. Cornell scale for depression in dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23:271–84.

De Figueiredo VLM. Desempenhos nas Duas Tarefas do Subteste Dígitos do WISC-III e do WAIS-III. Psicol Teor e Pesqui. 2007;23:313–8.

Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3rd ed. The Psychological Corporation. Pearson’s Clinical Assessment Group: San Antonio, TX; 1997.

Tombaugh TN. Trail Making Test A and B: Normative data stratified by age and education. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2004;19:203–14.

Brucki SMD, Malheiros SMF, Okamoto IH, Bertolucci PHF. Dados normativos para o teste de fluência verbal categoria animais em nosso meio. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1997;55:56–61.

Lino VTS, Pereira SRM, Camacho LAB, Filho STR, Buksman S. Adaptação transcultural da Escala de Independência em Atividades da Vida Diária (Escala de Katz). Cad Saúde Pública. 2008;24:103–12.

Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2412.

Macedo Montaño MBM, Ramos LR. Validade da versão em português da Clinical Dementia Rating. Rev Saude Publica. 2005;39:912–7.

Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2308.

Cole RJ, Kripke DF, Gruen W, Mullaney DJ, Gillin JC. Automatic Sleep/Wake Identification From Wrist Activity. Sleep 1992;15:461–9.

Camargos EF, Louzada FM, Nóbrega OT. Wrist actigraphy for measuring sleep in intervention studies with Alzheimer’s disease patients: Application, usefulness, and challenges. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17:475–88.

Sherman H, Castro G, Fletcher M, Hatlie M, Hibbert P, Jakob R, et al. Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: the conceptual framework. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2009;21:2–8.

Leite SN, Vasconcellos M, da PC. Adesão à terapêutica medicamentosa: elementos para a discussão de conceitos e pressupostos adotados na literatura. Cien Saude Colet. 2003;8:775–82.

Ferreira A de O. Guia Prático da Farmácia Magistral- Vol 1. 4th ed. Pharmabooks, São Paulo; 2011.

Aulton ME. Delineamento de Formas Farmacêuticas. 2a ed. Artmed, Porto Alegre, RS; 2005.

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–9.

McCleery J, Sharpley AL. Pharmacotherapies for sleep disturbances in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;11:1465–1858.

Scoralick FM, Louzada LL, Quintas JL, Naves JOS, Camargos EF, Nóbrega OT. Mirtazapine does not improve sleep disorders in Alzheimer’s disease: results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Psychogeriatrics. 2017;17:89–96.

Herring WJ, Ceesay P, Snyder E, Bliwise D, Budd K, Hutzelmann J, et al. Polysomnographic assessment of suvorexant in patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease dementia and insomnia: a randomized trial. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020;16:541–51.

Mouret J, Ruel D, Maillard F, Bianchi M. Zopiclone versus triazolam in insomniac geriatric patients: a specific increase in delta sleep with zopiclone. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;5:47–55.

Hemmeter U, Müller M, Bischof R, Annen B, Holsboer-Trachsler E. Effect of zopiclone and temazepam on sleep EEG parameters, psychomotor and memory functions in healthy elderly volunteers. Psychopharmacol (Berl). 2000;147:384–96.

Leufkens TRM, Ramaekers JG, de Weerd AW, Riedel WJ, Vermeeren A. Residual effects of zopiclone 7.5mg on highway driving performance in insomnia patients and healthy controls: a placebo controlled crossover study. Psychopharmacol (Berl). 2014;231:2785–98.

Wadworth AN, McTavish D. Zopiclone. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy as an hypnotic. Drugs Aging. 1993;3:441–59.

Roehrs TA, Diederichs C, Roth T. Pharmacology of benzodiazepine receptor agonist hypnotics. In: Therapy in sleep medicine. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, Elsevier; 2011. p. 99–108.

Olubodun JO, Ochs HR, Von Moltke LL, Roubenoff R, Hesse LM, Harmatz JS, et al. Pharmacokinetic properties of zolpidem in elderly and young adults: Possible modulation by testosterone in men. Br J Clin Pharm. 2003;56:297–304.

Cubała WJ, Wiglusz M, Burkiewicz A, Gałuszko-Węgielnik M. Zolpidem pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in metabolic interactions involving CYP3A: sex as a differentiating factor. Eur J Clin Pharm. 2010;66:955–955.

Sieghart W, Savić MM. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. CVI: GABA A Receptor Subtype- and Function-selective Ligands: Key Issues in Translation to Humans. Pharm Rev. 2018;70:836–78.

Korpi ER, Gründer G, Lüddens H. Drug interactions at GABAA receptors. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;67:113–59.

Kwakowsky A, Calvo-Flores Guzmán B, Pandya M, Turner C, Waldvogel HJ, Faull RL. GABA A receptor subunit expression changes in the human Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus, subiculum, entorhinal cortex and superior temporal gyrus. J Neurochem. 2018;145:374–92.

Rissman RA, Mobley WC. Implications for treatment: GABAA receptors in aging, Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2011;117:613–22.

Glass J, Lanctôt KL, Herrmann N, Sproule BA, Busto UE. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: Meta-analysis of risks and benefits. Br Med J. 2005;331:1169–73.

Darcourt G, Pringuey D, Salliere D, Lavoisy J. The safety and tolerability of zolpidem - an update. J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13:81–93.

Allain H, Bentué-Ferrer D, Tarral A, Gandon JM. Effects on postural oscillation and memory functions of a single dose of zolpidem 5mg, zopiclone 3.75mg and lormetazepam 1mg in elderly healthy subjects. A randomized, cross-over, double-blind study versus placebo. Eur J Clin Pharm. 2003;59:179–88.

Frey DJ, Ortega JD, Wiseman C, Farley CT, Wright KP. Influence of zolpidem and sleep inertia on balance and cognition during nighttime awakening: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:73–81.

Machado FV, Louzada LL, Cross NE, Camargos EF, Dang-Vu TT, Nóbrega OT. More than a quarter century of the most prescribed sleeping pill: Systematic review of zolpidem use by older adults. Exp Gerontol. 2020;136:110962.

Dehin O, Rundgren A, Borjesson L, Ekelund P, Gatzinska R, Hedenrud B, et al. Zopiclone to Geriatric Patients. Pharmacology. 1983;27:173–8.

Klimm HD, Dreyfus JF, Delmotte M. Zopiclone Versus Nitrazepam: a Double-Blind Comparative Study of Efficacy and Tolerance in Elderly Patients with Chronic Insomnia. Sleep. 1987;10:73–8.

Dehlin O, Bengtsson C, Rubin B. A comparison of zopiclone and propiomazine as hypnotics in outpatients: A multicentre, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group comparison of zopiclone and propiomazine in insomniacs. Curr Med Res Opin. 1997;13:565–72.

Dündar Y, Dodd S, Strobl J, Boland A, Dickson R, Walley T. Comparative efficacy of newer hypnotic drugs for the short-term management of insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2004;19:305–22.

Winkler A, Auer C, Doering BK, Rief W. Drug Treatment of Primary Insomnia: a Meta-Analysis of Polysomnographic Randomized Controlled Trials. CNS Drugs. 2014;28:799–816.

Louzada LL, Machado FV, Nóbrega OT, Camargos EF. Zopiclone to treat insomnia in older adults: a systematic review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;50:75–92.

Kaptchuk TJ, Miller FG. Placebo Effects in Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:8–9.

Finniss DG, Kaptchuk TJ, Miller F, Benedetti F. Biological, clinical, and ethical advances of placebo effects. Lancet. 2010;375:686–95.

Wager TD, Atlas LY. The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:403–18.

Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Neubauer DN, Heald JL. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;1313:307–49.

Funding

This research was funded by the Foundation for Research Support of the Brazilian Federal District (grant # 193.000.659-2015), by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development—Brazil (grant # 400927-2016-0), and by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—FinanceCode 001. OTN is recipient of a fellowship for productivity in research from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) (grant # 303540/2019-2). The authors report no conflicts with any product mentioned or concept discussed in this paper. This study was not supported by any manufacturer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, drafting and writing the paper. LLL and FVM participated in the acquisition of the data collection and BSBG in the analysis of the data for the work. OTN and EFC had substantial contribution in editing and revising critically the paper for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Louzada, L.L., Machado, F.V., Quintas, J.L. et al. The efficacy and safety of zolpidem and zopiclone to treat insomnia in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacol. 47, 570–579 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-021-01191-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-021-01191-3