Abstract

The vast majority of image-detected breast abnormalities are diagnosed by percutaneous core needle biopsy (CNB) in contemporary practice. For frankly malignant lesions diagnosed by CNB, the standard practice of excision and multimodality therapy have been well-defined. However, for high-risk and selected benign lesions diagnosed by CNB, there is less consensus on optimal patient management and the need for immediate surgical excision. Here we outline the arguments for and against the practice of routine surgical excision of commonly encountered high-risk and selected benign breast lesions diagnosed by CNB. The entities reviewed include atypical ductal hyperplasia, atypical lobular hyperplasia, lobular carcinoma in situ, intraductal papillomas, and radial scars. The data in the peer-reviewed literature confirm the benefits of a patient-centered, multidisciplinary approach that moves away from the reflexive “yes” or “no” for routine excision for a given pathologic diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Percutaneous core needle biopsy (CNB) under image guidance has been a standard part of the evaluation of nonpalpable breast lesions for over 30 years. Until relatively recently, most patients with high-risk and selected benign lesions diagnosed on CNB underwent immediate surgical excision to exclude an unsampled invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) near the CNB site. Upgrade rates in the early CNB literature were as high as 30–50% for many benign and atypical lesions1. Some of the variability in upgrade rates may be attributed to variations in the size of the biopsy device, with lower upgrade rates reported for 12-gauge or larger vacuum-assisted biopsies than 14-gauge ultrasound-guided CNB2. In addition, upgrades have been variably defined, with some authors classifying high-risk lesions diagnosed after excision of selected benign breast lesions as upgrades3,4,5,6. In this review, only a diagnosis of invasive carcinoma (any histology) or DCIS after immediate surgical excision is considered an upgrade. In contemporary practice, there is an active debate over whether more recent data provide sufficient evidence to offer selected patients surveillance instead of surgery1,7. In the absence of well-accepted consensus guidelines, recommendations for surgery versus observation are not uniform across institutions8,9,10. There are data to suggest that patients who are not referred for surgical consultation are less likely to adhere to follow-up imaging or chemoprevention11. However, the overall rates of uptake and adherence to chemoprevention among patients with high-risk lesions are generally low12,13.

There appears to be an emerging consensus on limiting the role of surgery for non-malignant CNB diagnoses when careful radiologic-pathologic correlation can be confirmed. Radiologic-pathologic correlation involves an assessment of whether the histologic findings in a CNB represent the targeted imaging abnormality and the extent to which the lesion and/or calcifications were removed. A diagnosis of invasive breast cancer or DCIS on excision (the appropriate definition of an upgrade) should not be regarded as a true upgrade if the CNB pathology did not fully account for the imaging findings. Cases with a suspicious, palpable mass, BI-RADS Category 5 imaging and co-existing lesions associated with breast cancer risk also should be excluded when upgrade rates are reported. The upgrade rates in recent studies with larger sample sizes, detailed radiologic-pathologic correlation, and strict criteria for upgrades are much lower than those reported earlier in the CNB era1,14.

Only a few small prospective studies of CNB with non-malignant lesions have been published and most clinical practice guidelines lack the specificity required for consistent application across different practice environments. Guidelines and consensus statements may include active surveillance as a vaguely defined “option” in “selected” cases without clear, reproducible criteria for the selection of cases for observation15,16. As a result, many patients with high-risk and selected benign lesions on CNB undergo immediate surgical excision. This article will review the evidence for and against immediate surgical excision of selected cases of ADH, pure lobular neoplasia (ALH and classic LCIS), radial scars and benign intraductal papillomas on CNB. The key arguments for and against immediate surgical excision are summarized in Table 1.

Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia (ADH)

Patients with ADH diagnosed on CNB should undergo immediate surgical excision

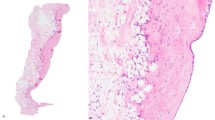

Histopathologically, ADH is defined as a monomorphic proliferation of cells with cytologic atypia and architectural complexity that lacks the necessary criteria for DCIS (Fig. 1). There is ample evidence in the literature to support immediate surgical excision of ADH diagnosed on CNB. Upgrade rates for ADH diagnosed on CNB have been reported to be as high as 30% to >50%17,18,19,20,21. In an analysis by Lewin et al. of 18 studies including over 3,000 excisions, the upgrade rate for ADH identified on CNB ranged from 13 to 56%, with a mean upgrade rate of 23%22. In other studies, some of which explicitly included radiological–pathological correlation, the average upgrade rate was approximately 20%23,24,25,26,27,28. In a recent meta-analysis of 6258 cases, the pooled upgrade rate for ADH was 29% and the upgrade rate specifically for cases with apparent complete removal of the imaging abnormality was 14%29. It also has been shown that ADH diagnosed on ultrasound-guided CNB with a 14-gauge device is more likely to be upgraded than 12-gauge or larger vacuum-assisted CNB18,30. Upgrades after ADH are more likely to be DCIS than invasive carcinoma and the invasive tumors are more likely to low-grade than high-grade28. The historically high upgrade rates for unselected cases of ADH in these and other studies18,26,27,28,31 and the fact some upgrades are invasive have contributed to the resistance to offering active surveillance for selected patients with ADH on CNB.

ADH is comprised of a monomorphic proliferation of cells with cytologic atypia and architectural complexity that do not completely fulfill the criteria for a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Examples are shown in images A–D (all images H&E at 200X magnification). ADH may present as an area of abnormal calcifications on screening mammography that is amenable to stereotactic-guided core needle biopsy (microcalcifications in images A and C).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (2021) recommend surgical excision when ADH is identified on CNB16. Similarly, the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBS) Consensus Guidelines state that because of the high risk of upgrade to carcinoma, excisional biopsy should be offered to patients15. The ASBS guidelines (2016) note the subtle distinctions between ADH and DCIS is some cases, and that there is a risk of missing malignant lesions when ADH is not excised routinely. The ASBS guidelines also note, however that selected patients with ADH can be safely observed and avoid surgery. In three studies, all ADH cases in which the lesion depicted on the mammogram was completely removed at 11-gauge vacuum-assisted stereotactic biopsy were free of carcinoma at surgical excision32,33,34. However, given the variability of opinion in the literature and the lack of large prospective studies, most cases of ADH should be surgically excised15.

Recent studies suggest surveillance may be appropriate for selected patients with ADH

Several studies provide evidence for the selection of patients with ADH who may be offered close clinical follow-up with imaging as an alternative to immediate surgical excision26,35,36,37,38. Surveillance may be a reasonable option in cases with detailed radiologic-pathologic correlation, no more than 2–3 foci of ADH in the CNB, and substantial removal of calcifications (≥ 50% in some studies; ≥ 90% in others) by vacuum-assisted CNB36,37,39. Features that still warrant immediate excision include suspicious ultrasound or MRI findings, intermediate-high grade nuclear atypia, and cellular necrosis. With four ongoing clinical trials of active surveillance for DCIS (COMET, LORD, LORIS, LORETTA), the reluctance to offering active surveillance to a carefully defined subset of patients with ADH seems paradoxical. It should be pointed out that limiting the role of immediate surgical excision does not mean a patient would never receive a recommendation for surgery. Surgery would remain an option, especially if there are any significant changes in imaging or clinical findings as the patient is followed. In essence, the change in clinical management could be thought of as retaining the option for “delayed surgery” in selected patients instead of mandatory immediate surgical excision for all patients40. Ideally, additional, multi-institutional prospective studies of ADH diagnosed on CNB would be conducted to confirm or further refine the selection of patients for observation41,42,43.

Atypical Lobular Hyperplasia (ALH) and class Lobular Carcinoma In Situ (LCIS)

Patients with ALH and classic LCIS diagnosed on CNB should undergo immediate surgical excision

Lewin et al. analyzed 13 retrospective studies with over 900 excisions and showed a wide range of upgrade rates after excisional biopsy for ALH diagnosed on CNB between 0 and 67% with a reported mean of 9%22,28,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. The upgrade rates for LCIS also showed a broad range, from 5 to 60% with a mean of 18%22,28,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. Based on the relatively broad range of reported upgrade rates, some authors to recommend caution in the interpretation of the data55. Buckley et al. have pointed out that many series of classic LCIS are single-institution, retrospective studies with relatively small sample sizes and limited or no follow-up for patients who do not undergo excision55. Without long-term follow-up, these studies may significantly underestimate the rate of development of carcinoma after a CNB diagnosis of LCIS. These potential limitations likely apply to the breast CNB literature in general56. The size of the biopsy device also may influence upgrade rates for ALH and classic LCIS, with a higher likelihood of upgrade for 14-gauge CNBs2.

Middleton et al. evaluated the efficacy of using standard radiologic and histologic criteria to guide the management of patients with classic LCIS and ALH44. Surgical excision was recommended for all cases of radiologic-pathologic discordance and was more likely for cases of LCIS rather than ALH, for targeted rather than incidental lesions, in cases with five or fewer cores taken, and for mass lesions. There were upgrades among patients offered immediate surgical excision and those followed with clinical and radiological surveillance. Of the 20 patients with immediate excision, 8 (40%) were upgraded44. Nonoperative management was offered to 104 patients, and 5 (5%) were upgraded to malignancy at a subsequent surgical excision44.

In a study of 8205 14-gauge ultrasound-guided CNB by Ferré et al. there were 20 CNB with lobular neoplasia and the upgrade rate was 25% (5/20)54, supporting the practice of routine surgical excision of lobular neoplasia. Rendi et al. reported a study of 106 cases of lobular neoplasia diagnosed on CNB with surgical excision follow-up for 93 cases: 25 with lobular neoplasia and ADH and 68 cases with lobular neoplasia alone50. There were no upgrades among normal-risk patients who underwent CNB to assess calcifications identified on routine mammographic screening50. Patients with any other imaging indication (high-risk screening, determination of extent of disease, follow-up after lumpectomy, evaluation of a clinical finding) or an imaging finding (mass, architectural distortion, MRI enhancement) were found to have a nonzero risk of upgrade at excision50. Interestingly, of the 7 total upgraded cases (4 with ADH, 3 with lobular neoplasia alone), 5 underwent biopsy for non-mass enhancement on MRI. The authors recommended surgical excision for lobular neoplasia on CNB for all patients considered high-risk on the basis of personal or family history regardless of whether mammography or MRI is used as the screening modality50.

Both the ASBS (2016) and NCCN (2021) support surgical excision of LCIS variants diagnosed on CNB15,16. Pleomorphic LCIS is a less common, high-grade variant of LCIS57. Histopathologically, it differs from classical LCIS in that the cells are higher grade with pleomorphic features when compared to classic LCIS with 2–3X variation in size and expansile central necrosis with calcification may be seen (Fig. 2). Because of the propensity to calcify, pleomorphic LCIS may be identified mammographically and may represent the targeted lesion of the percutaneous CNB rather that an incidental finding. In a series that included 15 cases of pleomorphic LCIS diagnosed on CNB, upgrade rate to malignancy was 27% (4/15)57. In another recent study of pleomorphic and florid LCIS, the overall upgrade rate was 19% (6/32)58. Of the 6 cases upgraded at excision, 5 were radiologic-pathologic concordant. As a result of the high upgrade rate to DCIS or invasive cancer at surgical excision after diagnosis on CNB, LCIS variants should be treated with complete surgical excision58,59,60.

H&E 100X image A and Immunostain for e-cadherin in B. H&E shows markedly distended terminal duct lobular units comprised of solid pattern of cells with cytologic atypia that lack cohesion. Central necrosis with calcifications is readily apparent. An immunostain for e-cadherin demonstrates an absence of staining within the proliferation, though staining is retained by the myoepithelial cells surrounding the ducts and lobules. Unlike classic LCIS that is radiographically occult and is an incidental finding on core needle biopsies, pleomorphic LCIS often presents as abnormal calcifications seen on imaging.

Recent studies suggest surveillance may be appropriate for many patients with ALH and classic LCIS

Several recent studies suggest that upgrade rates are less than 5% in a subset of lobular neoplasia on CNB with no other lesion requiring excision (ADH, papilloma, radial scar) and radiologic-pathologic concordance24,44,61,62. The upgrade rate for incidental ALH and classical LCIS in cases with radiological-pathological correlation is approximately 3%28,50,51,52,53,63. The lower upgrade rates for pure lobular neoplasia diagnosed on CNB are consistent with the data from retrospective studies of patients who did not undergo immediate surgery44,64 and a recent prospective study of classic LCIS (TBCRC 020)65.

In a study of 104 patients at MD Anderson Cancer Center with classic-type lobular neoplasia (ALH or LCIS) who were followed clinically and radiologically for a mean of 40.8 months (range 5.3–103.2), Middleton et al. reported that 2 (1.9%) developed breast cancer near the CNB site44. Similar findings were reported in a prior study from MD Anderson and a series from Mt. Sinai in New York52,66. Recommendations for surveillance were based on review at a weekly multidisciplinary conference that included radiology, surgery and pathology. Exclusion criteria included pleomorphic or florid LCIS, coexisting radial scars, and co-existing papillomas44. Based on these data, the authors recommend surveillance for patients with ALH or classic LCIS in < 3 terminal duct lobular units (TDLU) in the CNB and radiologic-pathologic correlation44.

Laws et al. recently reported a study of 80 patients at Brigham and Women’s Hospital with radiologically concordant pure ALH or classic LCIS diagnosed on CNB who were offered observation64. With a median follow-up of 27 months, none of the patients developed an ipsilateral breast cancer in the same quadrant as the CNB site. The 3-year risk of failure for conservative management was 6.2%. All of the failures were excisions prompted by evolving imaging findings at the CNB site, and the final pathology was benign in all of these cases64. These data provide further evidence for the safety of non-surgical management of ALH and classic LCIS.

The results of a multi-institutional trial for classic-type lobular neoplasia diagnosed on CNB (TBCRC 020) were recently reported65. The goal of TBCRC 020 was to determine the upgrade rate after CNB. Cases with a palpable mass, BI-RADS Category 5, prior history or current diagnosis of breast cancer, or co-existing ADH or LCIS variants were excluded65. The upgrade rate for classic-type lobular neoplasia was 3% based on local pathology review and 1% by central pathology review65. The data from TBCRC 020 provide additional evidence for the safety of delaying surgical excision in carefully selected cases of ALH and classic LCIS.

Classic LCIS and ALH are often incidental findings that are not associated with mammographically detected calcifications. The ASBS (2016) no longer advocates routine excision of classic LCIS and ALH when radiologic-pathologic diagnoses are concordant and no other high-risk lesion requiring excision is present15. Specifically, normal risk patients who undergo CNB to assess calcifications found by routine mammographic screening yielding lobular neoplasia alone may not require excisional biopsy50. The NCCN continues to recommend surgical excision when multiple foci of ALH or LCIS are present in the CNB, particularly when extensive LCIS is present involving more than 4 TDLUs16. In cases of concordant ALH or classic LCIS, patients may be offered observation using shared decision making between the patient and physician as well as planned imaging follow-up50. Patients with variants of LCIS (i.e., pleomorphic and florid LCIS) diagnosed on CNB should undergo immediate surgical excision.

Radial scars without atypia

Patients with radial scars diagnosed on CNB should undergo immediate surgical excision

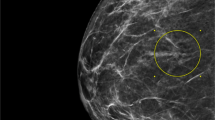

Radial scars are benign sclerosing lesions of the breast characterized by a central fibroelastotic core. Benign glands radiate from the center, and other features such as usual ductal hyperplasia, apocrine metaplasia, and cyst formation are commonly seen (Fig. 3). When diagnosis is made by CNB, the lesion may be somewhat more fragmented making it difficult to appreciate the underlying lesion (Fig. 4). Though radial scars are benign, many studies have shown a significant association with occult synchronous breast cancer67,68,69. Radial scar diagnosed by CNB has become somewhat more prevalent with the widespread use of 3D mammography or tomosynthesis that detects more subtle architectural distortions70.

There is a central fibroelastic core that is characteristic with entrapped benign glands. Epithelial hyperplasia, apocrine metaplasia, sclerosing adenosis and cyst formation may be seen. While the diagnosis is often apparent on surgical excisions, it may be more difficult to recognize on small, fragmented core tissue from a needle biopsy.

3D Mammography demonstrated an area of architectural distortion that was biopsied using stereotactic guidance. A low power view at 20X magnification is seen in A. The fibroelastotic stroma with glandular proliferations radiating from the center are not as apparent in this CNB as the excision from Fig. 3. A 40X view in B shows part of a fibroelastotic core. 100X magnification shows an area of apocrine metaplasia in C and cystic dilation of glands in D. The constellation of findings are consistent with a radial scar in this setting.

When radial scars are diagnosed by core needle biopsy, observed upgrade rates to carcinoma are as high as 16%28. In addition, when radial scars are excised, additional high-risk lesions such as ADH and LCIS may be identified in up to 26% of excision specimens71. Certainly, the upgrade to frank malignancy changes the management of patients presenting initially with radial scar. But management may also change significantly based up the upgrade to atypia. Patients may be referred to high risk clinics where chemoprevention or increased screening protocols could be initiated. Some authors recommend excision for radial scars > 10 mm in size72,73. However, the association of size with likelihood of upgrade has not been consistently observed74. In current practice, we still lack a clear consensus on which patients with radial scars may be observed and most patients are still referred for surgical consultation. Given the ease of excision, the potential change in patient management, and risk of carcinoma, patients should be offered surgical excision. Large radial scars and those associated with ADH, ALH, or LCIS should be excised3.

Recent studies suggest surveillance may be appropriate for many patients with radial scars without atypia

In a recent meta-analysis by Farshid et al. of 3163 radial scars from 49 studies, the overall upgrade rate was ~7% and two-thirds of the upgrades were DCIS75. Among radial scars without atypia diagnosed on vacuum-assisted CNB, 1% were upgraded (all DCIS). In contrast, radial scars with atypia diagnosed with a 14-gauge biopsy device had an upgrade rate of 29%75. In a recent series of radial scars without atypia, the upgrade rate was 1% (DCIS only) and none of the patients followed with active surveillance developed an ipsilateral breast cancer76. Other studies have shown similar results, with no subsequent cancers at the CNB site and a low rate of developing breast cancer at other sites in the same breast74,77. Some authors recommend surgical excision of all radial scars based on the possibility of finding additional high-risk lesions that would warrant high-risk follow-up and consideration of chemoprevention (i.e., ADH, ALH, or classic LCIS)3,4 but uptake and adherence among these patients may be low12,13.

Intraductal papillomas

Patients with intraductal papillomas diagnosed on CNB should undergo immediate surgical excision

Given the risk of upgrade5,6,21,78,79,80 and the potential for significant interobserver variability in the classification of papillary lesions81, patients should undergo immediate surgical excision to avoid the underestimation of malignancy. In a series of 814 consecutive CNB for screen-detected lesions from 2005 to 2014, Farshid and Gill reported an upgrade rate of 30.8% (32/104) for a combined category representing papillary lesions with and without atypia21. The authors noted that, at the time of their publication, the National Health System Breast Screening Program (NHSBSP) Clinical Guidelines for the United Kingdom (2016) recommended complete removal of papillary lesions (either by surgical excision for lesions with epithelial atypia or vacuum-assisted excision for those without atypia)82. In a series of 234 CNB from 2001 to 2009, Rizzo et al. reported an upgrade rate of 8.9% (21/234) for benign papillomas and 2 of the upgrades were invasive5. In an international, multicenter study of 188 benign papillomas diagnosed on CNB, Foley et al. reported upgrades to invasive carcinoma or DCIS in 14.4% (27/188)78. Glenn et al. reported an upgrade to malignancy in 4.7% (7/146) of papillomas without atypia6. Chen et al. reported a lower upgrade rate of 3.7% (8/206) for benign papillomas, and all of the upgraded cases were considered radiologically concordant83. Based on the unacceptably broad range of upgrade rates in these and other studies79,80 and the potential for upgrades in radiologically concordant cases83, immediate surgical excision is the most appropriate clinical management for papillomas diagnosed on CNB.

Recent studies suggest surveillance may be appropriate for many patients with benign intraductal papillomas

Intraductal papillomas of the breast are common lesions seen in routine practice (Fig. 5). High upgrade rates have been reported for papillary lesions diagnosed on CNB5,6,21,78,79,80, but what is most important is the rate of upgrade to invasive carcinoma or DCIS specifically for radiologically concordant papillomas without atypia. Although some studies have shown high interobserver variability in the classification of papillary lesions81, others have shown substantial or fair agreement among pathologists for benign and atypical papillomas84,85. The studies reported by Rizzo et al.5, Glenn et al.6, Foley et al.78 and others79,80 lack detailed radiologic-pathologic correlation. In the study reported by Chen et al. all of the upgraded cases were reported to be radiologically concordant83. However, many of the upgrades were in patients with ≥ 20% lifetime risk of breast cancer and/or a history of atypia or breast cancer83. Upgrade rates for papillomas are lower in studies that exclude patients with BI-RADS 5 or discordant imaging, restrict the definition of an upgrade to invasive carcinoma or DCIS, and limit the study population to patients with an average risk of breast cancer83,86. Studies with high upgrade rates often lack clear criteria for which patients were referred for surgery versus nonoperative management, raising the possibility selection bias influenced the results. In the series reported by Rizzo et al. surgical excision was performed in ~75% of cases5. Of the 100 patients who did not undergo excision, 59 had imaging follow-up (mean of 86 months) that was normal or benign (BI-RADS 1, 2, or 3)5. The possibility that patients at the highest risk of upgrade were selected for immediate surgical excision cannot be excluded. Upgrade rates for papillomas also are higher when smaller (i.e., 14-gauge) biopsy devices are used2.

H&E images, 20X magnification in A and 200X in B. Intraductal papillomas are often quite fragmented when examined on CNB specimens as can be seen in the low power image in A. Fragments of the dilated duct surrounding the intraductal papilloma may also be seen. The higher power view in B demonstrates an arborizing pattern of papillae with fibrovascular cores. Both an epithelial and myoepithelial cell layer is identified. Intraductal papillomas may become sclerotic, calcify and even infarct.

Several carefully conducted retrospective studies provide support for nonoperative management of benign papillomas. Swapp et al. reported a series of 224 solitary, benign, radiologically concordant intraductal papillomas with no upgrades in the 77 patients who underwent immediate excision87. There were no upgrades in a series of incidental benign papillomas measuring < 2 mm (‘micropapillomas’) reported by Jaffer et al.88. In the series reported by Swapp et al., 100 patients were followed with observation and none of them developed breast cancer with a mean follow-up of 36 months87. Grimm et al. reported similar findings in a series of 252 benign, radiologically concordant papillomas with at least 2 years of imaging follow-up89.

Ma et al. recently reported a series of papillomas prospectively evaluated at a biweekly multidisciplinary conference at Emory University90. Cases were evaluated in real time for patient care and surveillance was recommended for benign papillomas with radiologic-pathologic correlation and at least 1/3 of the imaging abnormality removed, ≤ 2 foci of ADH adjacent to the papilloma in the CNB (n = 6), and ALH involving or adjacent to the papilloma in the CNB (n = 7)90. In cases of with ADH involving the papilloma or adjacent ADH with intermediate-high grade nuclear atypia suspicious for DCIS in the CNB, patients were referred for surgical excision. With a mean follow up of 18.9 months (range 6.1–42.0 months), the 73 patients who did not have surgery had stable imaging findings and none developed breast cancer90. These findings are similar to several retrospective studies of nonoperative management with 3–5 years of clinical and radiological follow-up. In those studies, the rate of development of invasive carcinoma or DCIS in patients who did not undergo immediate surgical excision ranged from 0 to 4%80,87,91,92,93,94,95,96,97.

Results of a multi-institutional trial for papillomas without atypia diagnosed on CNB were recently reported by the TBCRC98. The primary endpoint of TBCRC 034 was a pre-defined rule that surgery would not be required if the upgrade rate for benign papillomas diagnosed on CNB was ≤ 3%98. Cases with a palpable mass, nipple discharge, BI-RADS 5 category, concurrent or prior history of breast cancer, or co-existing ADH or LCIS variants were excluded65,98. The upgrade rate for papillomas without atypia (based on local pathology review) was 1.7% in TBCRC 034, providing further support for the nonoperative management of benign intraductal papillomas98.

Discussion

The potential for upgrade to malignancy at surgical excision because of the sampling volume limitation of CNB as well as possible targeting inaccuracy remain the principal reasons for immediate surgical management of high-risk and selected benign lesions of the breast. There is a persistent concern for underestimating malignancy on CNB (i.e., missing a diagnosis of carcinoma) in this patient population. There appears to be an emerging consensus in the current peer-reviewed literature for limiting the role of immediate surgery for many high-risk and selected benign lesions of the breast diagnosed on CNB (Table 1). Prospective data similar to large oncology clinical trials with thousands of patients will not be forthcoming. The few prospective studies that have been published and the most carefully conducted retrospective studies are already guiding clinical practice in many institutions.

One of the key questions in contemporary practice is whether immediate surgical excision avoids underdiagnosis and undertreatment of malignancy or represents overtreatment of patients with non-malignant diagnoses who could be managed with close observation. Another key question is which patients should be offered nonoperative management. Active surveillance could be offered to patients who would have been offered nonoperative management in the TBCRC trials65,98. The data from those trials suggest that an upgrade rate of ≤ 3% could be a reasonable threshold for offering surveillance versus surgery. This threshold is similar to the upgrade rate of ≤ 2% for BI-RADS Category 3 lesions which are routinely followed with repeat imaging at 6 months99.

In addition to the concern for underestimating malignancy, some experts advocate surgery for some benign lesions (e.g., radial scars and papillomas without atypia) based on the possibility of finding additional atypical lesions (i.e., ADH, ALH or classic LCIS) in the excision specimen that would warrant high-risk follow-up and consideration of chemoprevention3,4. It should be noted that ADH, ALH, and classic LCIS were present in only 4% of surgical specimens from patients with benign papillomas in TBCRC 03498. These data indicate that routine surgical excision would not change the clinical management for the vast majority of patients who match the eligibility criteria for that trial.

Clinical management should be based on a more nuanced approach that incorporates radiologic and pathologic correlation and patient preference. The risk calculation for patients with the same pathologic diagnosis seen on CNB may be quite different. For example, a 40-year-old with 4 cm of suspicious calcifications seen on mammogram with a diagnosis of ADH is very different from an 88-year-old with a small cluster of indeterminate calcifications completely excised by CNB. Pathologic diagnoses on CNB cannot be interpreted in isolation. Clinical and radiologic context are essential. The financial and psychologic cost of surgical excision in comparison with radiologic surveillance must be examined, especially in the context of any anxiety associated with radiological surveillance. If close observation and follow-up is chosen for lesions with a lower likelihood of upgrade, the patient must play an active role in decision making. Finally, if surveillance is chosen, patient compliance with follow-up must be considered15.

References

Calhoun BC. Core needle biopsy of the breast: An evaluation of contemporary data. Surg Pathol Clin. 11, 1–16 (2018).

Londero V, Zuiani C, Linda A, Battigelli L, Brondani G, Bazzocchi M. Borderline breast lesions: Comparison of malignancy underestimation rates with 14-gauge core needle biopsy versus 11-gauge vacuum-assisted device. Eur Radiol. 21, 1200–6 (2011).

Miller CL, West JA, Bettini AC, Koerner FC, Gudewicz TM, Freer PE, et al. Surgical excision of radial scars diagnosed by core biopsy may help predict future risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 145, 331–8 (2014).

Phantana-Angkool A, Forster MR, Warren YE, Livasy CA, Sobel AH, Beasley LM, et al. Rate of radial scars by core biopsy and upgrading to malignancy or high-risk lesions before and after introduction of digital breast tomosynthesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 173, 23–9 (2019).

Rizzo M, Linebarger J, Lowe MC, Pan L, Gabram SG, Vasquez L, et al. Management of papillary breast lesions diagnosed on core-needle biopsy: Clinical pathologic and radiologic analysis of 276 cases with surgical follow-up. J Am Coll Surg. 214, 280–7 (2012).

Glenn ME, Throckmorton AD, Thomison JB, 3rd, Bienkowski RS. Papillomas of the breast 15 mm or smaller: 4-year experience in a community-based dedicated breast imaging clinic. Ann Surg Oncol. 22, 1133–9 (2015).

Nakhlis F. How do we approach benign proliferative lesions? Curr Oncol Rep. 20, 34 (2018).

Georgian-Smith D, Lawton TJ. Variations in physician recommendations for surgery after diagnosis of a high-risk lesion on breast core needle biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 198, 256–63 (2012).

Kappel C, Seely J, Watters J, Arnaout A, Cordeiro E. A survey of Canadian breast health professionals’ recommendations for high-risk benign breast disease. Can J Surg. 62, 358–60 (2019).

Nizri E, Schneebaum S, Klausner JM, Menes TS. Current management practice of breast borderline lesions--need for further research and guidelines. Am J Surg. 203, 721–5 (2012).

Gao Y, Albert M, Young Lin LL, Lewin AA, Babb JS, Heller SL, et al. What happens after a diagnosis of high-risk breast lesion at stereotactic vacuum-assisted biopsy? An observational study of postdiagnosis management and imaging adherence. Radiology. 287, 423–31 (2018).

Ropka ME, Keim J, Philbrick JT. Patient decisions about breast cancer chemoprevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 28, 3090–5 (2010).

Smith SG, Sestak I, Forster A, Partridge A, Side L, Wolf MS, et al. Factors affecting uptake and adherence to breast cancer chemoprevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 27, 575–90 (2016).

Calhoun BC, Collins LC. Recommendations for excision following core needle biopsy of the breast: a contemporary evaluation of the literature. Histopathology. 68, 138–51 (2016).

American Society of Breast Surgeons Official Statenment: Consensus Guideline on Concordance Assessment of Image-Guided Breast Biopsies and Management of Borderline or High-Risk Lesions 2016 [Available from: https://www.breastsurgeons.org/docs/statements/Consensus-Guideline-on-Concordance-Assessment-of-Image-Guided-Breast-Biopsies.pdf?v2.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines Version 1.2021: Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis 2021 [Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf.

Youn I, Kim MJ, Moon HJ, Kim EK. Absence of residual microcalcifications in atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed via stereotactic vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: Is surgical excision obviated? J Breast Cancer. 17, 265–9 (2014).

Mesurolle B, Perez JC, Azzumea F, Lemercier E, Xie X, Aldis A, et al. Atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed at sonographically guided core needle biopsy: Frequency, final surgical outcome, and factors associated with underestimation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 202, 1389–94 (2014).

Caplain A, Drouet Y, Peyron M, Peix M, Faure C, Chassagne-Clement C, et al. Management of patients diagnosed with atypical ductal hyperplasia by vacuum-assisted core biopsy: a prospective assessment of the guidelines used at our institution. Am J Surg. 208, 260–7 (2014).

Eby PR, Ochsner JE, DeMartini WB, Allison KH, Peacock S, Lehman CD. Frequency and upgrade rates of atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed at stereotactic vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: 9-versus 11-gauge. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 192, 229-34 (2009).

Farshid G, Gill PG. Contemporary indications for diagnostic open biopsy in women assessed for screen-detected breast lesions: A ten-year, single institution series of 814 consecutive cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 162, 49–58 (2017).

Lewin AA, Mercado CL. Atypical ductal hyperplasia and lobular neoplasia: Update and easing of guidelines. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 214, 265–75 (2020).

Wagoner MJ, Laronga C, Acs G. Extent and histologic pattern of atypical ductal hyperplasia present on core needle biopsy specimens of the breast can predict ductal carcinoma in situ in subsequent excision. Am J Clin Pathol. 131, 112–21 (2009).

Kohr JR, Eby PR, Allison KH, DeMartini WB, Gutierrez RL, Peacock S, et al. Risk of upgrade of atypical ductal hyperplasia after stereotactic breast biopsy: effects of number of foci and complete removal of calcifications. Radiology. 255, 723–30 (2010).

McGhan LJ, Pockaj BA, Wasif N, Giurescu ME, McCullough AE, Gray RJ. Atypical ductal hyperplasia on core biopsy: an automatic trigger for excisional biopsy? Ann Surg Oncol. 19, 3264–9 (2012).

Khoury T, Chen X, Wang D, Kumar P, Qin M, Liu S, et al. Nomogram to predict the likelihood of upgrade of atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed on a core needle biopsy in mammographically detected lesions. Histopathology. 67, 106–20 (2015).

Menes TS, Rosenberg R, Balch S, Jaffer S, Kerlikowske K, Miglioretti DL. Upgrade of high-risk breast lesions detected on mammography in the breast cancer surveillance consortium. Am J Surg. 207, 24–31 (2014).

Mooney KL, Bassett LW, Apple SK. Upgrade rates of high-risk breast lesions diagnosed on core needle biopsy: a single-institution experience and literature review. Mod Pathol. 29, 1471–84 (2016).

Schiaffino S, Calabrese M, Melani EF, Trimboli RM, Cozzi A, Carbonaro LA, et al. Upgrade rate of percutaneously diagnosed pure atypical ductal hyperplasia: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 6458 lesions. Radiology. 294, 76–86 (2020).

Lacambra MD, Lam CC, Mendoza P, Chan SK, Yu AM, Tsang JY, et al. Biopsy sampling of breast lesions: comparison of core needle- and vacuum-assisted breast biopsies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 132, 917–23 (2012).

Allison KH, Eby PR, Kohr J, DeMartini WB, Lehman CD. Atypical ductal hyperplasia on vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: suspicion for ductal carcinoma in situ can stratify patients at high risk for upgrade. Hum Pathol. 42, 41–50 (2011).

Adrales G, Turk P, Wallace T, Bird R, Norton HJ, Greene F. Is surgical excision necessary for atypical ductal hyperplasia of the breast diagnosed by Mammotome? Am J Surg. 180, 313–5 (2000).

Liberman L, Smolkin JH, Dershaw DD, Morris EA, Abramson AF, Rosen PP. Calcification retrieval at stereotactic, 11-gauge, directional, vacuum-assisted breast biopsy. Radiology. 208, 251–60 (1998).

Philpotts LE, Lee CH, Horvath LJ, Lange RC, Carter D, Tocino I. Underestimation of breast cancer with II-gauge vacuum suction biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 175, 1047–50 (2000).

Menen RS, Ganesan N, Bevers T, Ying J, Coyne R, Lane D, et al. Long-term safety of observation in selected women following core biopsy diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia. Ann Surg Oncol. 24, 70–6 (2017).

Peña A, Shah SS, Fazzio RT, Hoskin TL, Brahmbhatt RD, Hieken TJ, et al. Multivariate model to identify women at low risk of cancer upgrade after a core needle biopsy diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 164, 295–304 (2017).

Li X, Ma Z, Styblo TM, Arciero CA, Wang H, Cohen MA. Management of high-risk breast lesions diagnosed on core biopsies and experiences from prospective high-risk breast lesion conferences at an academic institution. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 185, 573–81 (2021).

Schiaffino S, Massone E, Gristina L, Fregatti P, Rescinito G, Villa A, et al. Vacuum assisted breast biopsy (VAB) excision of subcentimeter microcalcifications as an alternative to open biopsy for atypical ductal hyperplasia. Br J Radiol. 91, 20180003 (2018).

Kilgore LJ, Yi M, Bevers T, Coyne R, Lazzaro M, Lane D, et al. Risk of breast cancer in selected women with atypical ductal hyperplasia who do not undergo surgical excision. Ann Surg. Mar. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004849 [Epub ahead of print]. (2021).

Marti JL. ASO Author reflections: “High-Risk” lesions of the breast: Low risk of cancer, high risk of overtreatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 28, 5156–7 (2021).

Makretsov N. Now, later of never: multicenter randomized controlled trial call--is surgery necessary after atypical breast core biopsy results in mammographic screening settings? Int J Surg Oncol. 2015, 192579 (2015).

Farshid G, Edwards S, Kollias J, Gill PG. Active surveillance of women diagnosed with atypical ductal hyperplasia on core needle biopsy may spare many women potentially unnecessary surgery, but at the risk of undertreatment for a minority: 10-year surgical outcomes of 114 consecutive cases from a single center. Mod Pathol. 31, 395–405 (2018).

Khoury T, Jabbour N, Peng X, Yan L, Quinn M. Atypical ductal hyperplasia and those bordering on ductal carcinoma in situ should be included in the active surveillance clinical trials. Am J Clin Pathol. 153, 131–8 (2020).

Middleton LP, Sneige N, Coyne R, Shen Y, Dong W, Dempsey P, et al. Most lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical lobular hyperplasia diagnosed on core needle biopsy can be managed clinically with radiologic follow-up in a multidisciplinary setting. Cancer Med. 3, 492–9 (2014).

Sen LQ, Berg WA, Hooley RJ, Carter GJ, Desouki MM, Sumkin JH. Core breast biopsies showing lobular carcinoma in situ should be excised and surveillance is reasonable for atypical lobular hyperplasia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 207, 1132–45 (2016).

Londero V, Zuiani C, Linda A, Girometti R, Bazzocchi M, Sardanelli F. High-risk breast lesions at imaging-guided needle biopsy: usefulness of MRI for treatment decision. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 199, W240–50 (2012).

Khoury T, Li Z, Sanati S, Desouki MM, Chen X, Wang D, et al. The risk of upgrade for atypical ductal hyperplasia detected on magnetic resonance imaging-guided biopsy: a study of 100 cases from four academic institutions. Histopathology. 68, 713–21 (2016).

Rakha EA, Lee AH, Jenkins JA, Murphy AE, Hamilton LJ, Ellis IO. Characterization and outcome of breast needle core biopsy diagnoses of lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3) in abnormalities detected by mammographic screening. Int J Cancer. 129, 1417–24 (2011).

Allen S, Levine EA, Lesko N, Howard-Mcnatt M. Is excisional biopsy and chemoprevention warranted in patients with atypical lobular hyperplasia on core biopsy? Am Surg. 81, 876–8 (2015).

Rendi MH, Dintzis SM, Lehman CD, Calhoun KE, Allison KH. Lobular in-situ neoplasia on breast core needle biopsy: imaging indication and pathologic extent can identify which patients require excisional biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 19, 914–21 (2012).

Subhawong AP, Subhawong TK, Khouri N, Tsangaris T, Nassar H. Incidental minimal atypical lobular hyperplasia on core needle biopsy: correlation with findings on follow-up excision. Am J Surg Pathol. 34, 822–8 (2010).

Shah-Khan MG, Geiger XJ, Reynolds C, Jakub JW, Deperi ER, Glazebrook KN. Long-term follow-up of lobular neoplasia (atypical lobular hyperplasia/lobular carcinoma in situ) diagnosed on core needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 19, 3131–8 (2012).

Murray MP, Luedtke C, Liberman L, Nehhozina T, Akram M, Brogi E. Classic lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical lobular hyperplasia at percutaneous breast core biopsy: Outcomes of prospective excision. Cancer. 119, 1073–9 (2013).

Ferre R, Omeroglu A, Mesurolle B. Sonographic appearance of lesions diagnosed as lobular neoplasia at sonographically guided biopsies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 208, 669–75 (2017).

Buckley ES, Webster F, Hiller JE, Roder DM, Farshid G. A systematic review of surgical biopsy for LCIS found at core needle biopsy - do we have the answer yet? Eur J Surg Oncol. 40, 168-75 (2014).

Georgian-Smith D, Lawton TJ. Controversies on the management of high-risk lesions at core biopsy from a radiology/pathology perspective. Radiol Clin North Am. 48, 999–1012 (2010).

Savage JL, Jeffries DO, Noroozian M, Sabel MS, Jorns JM, Helvie MA. Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ: imaging features, upgrade rate, and clinical outcomes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 211, 462–7 (2018).

Kuba MG, Murray MP, Coffey K, Calle C, Morrow M, Brogi E. Morphologic subtypes of lobular carcinoma in situ diagnosed on core needle biopsy: clinicopathologic features and findings at follow-up excision. Mod Pathol. 34, 1495–506 (2021).

Downs-Kelly E, Bell D, Perkins GH, Sneige N, Middleton LP. Clinical implications of margin involvement by pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 135, 737–43 (2011).

Shamir ER, Chen YY, Chu T, Pekmezci M, Rabban JT, Krings G. Pleomorphic and florid lobular carcinoma in situ variants of the breast: A clinicopathologic study of 85 cases with and without invasive carcinoma from a single academic center. Am J Surg Pathol. 43, 399–408 (2019).

VandenBussche CJ, Khouri N, Sbaity E, Tsangaris TN, Vang R, Tatsas A, et al. Borderline atypical ductal hyperplasia/low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ on breast needle core biopsy should be managed conservatively. Am J Surg Pathol. 37, 913–23 (2013).

Pawloski KR, Christian N, Knezevic A, Wen HY, Van Zee KJ, Morrow M, et al. Atypical ductal hyperplasia bordering on DCIS on core biopsy is associated with higher risk of upgrade than conventional atypical ductal hyperplasia. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 184, 873–80 (2020).

Nagi CS, O’Donnell JE, Tismenetsky M, Bleiweiss IJ, Jaffer SM. Lobular neoplasia on core needle biopsy does not require excision. Cancer. 112, 2152–8 (2008).

Laws A, Katlin F, Nakhlis F, Chikarmane SA, Schnitt SJ, King TA. Atypical lobular hyperplasia and classic lobular carcinoma in situ can be safely managed without surgical excision. Ann Surg Oncol. 29, 1660–7 (2022).

Nakhlis F, Gilmore L, Gelman R, Bedrosian I, Ludwig K, Hwang ES, et al. Incidence of adjacent synchronous invasive carcinoma and/or ductal carcinoma in-situ in patients with lobular neoplasia on core biopsy: Results from a prospective multi-institutional registry (TBCRC 020). Ann Surg Oncol. 23, 722–8 (2016).

Schmidt H, Arditi B, Wooster M, Weltz C, Margolies L, Bleiweiss I, et al. Observation versus excision of lobular neoplasia on core needle biopsy of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 168, 649–54 (2018).

Doyle EM, Banville N, Quinn CM, Flanagan F, O’Doherty A, Hill AD, et al. Radial scars/complex sclerosing lesions and malignancy in a screening programme: incidence and histological features revisited. Histopathology. 50, 607–14 (2007).

Becker L, Trop I, David J, Latour M, Ouimet-Oliva D, Gaboury L, et al. Management of radial scars found at percutaneous breast biopsy. Can Assoc Radiol J. 57, 72–8 (2006).

Lopez-Medina A, Cintora E, Mugica B, Opere E, Vela AC, Ibanez T. Radial scars diagnosed at stereotactic core-needle biopsy: surgical biopsy findings. Eur Radiol. 16, 1803–10 (2006).

Pujara AC, Hui J, Wang LC. Architectural distortion in the era of digital breast tomosynthesis: outcomes and implications for management. Clin Imaging. 54, 133–7 (2019).

Li Z, Ranade A, Zhao C. Pathologic findings of follow-up surgical excision for radial scar on breast core needle biopsy. Hum Pathol. 48, 76–80 (2016).

Neal L, Sandhu NP, Hieken TJ, Glazebrook KN, Mac Bride MB, Dilaveri CA, et al. Diagnosis and management of benign, atypical, and indeterminate breast lesions detected on core needle biopsy. Mayo Clin Proc. 89, 536–47 (2014).

Nassar A, Conners AL, Celik B, Jenkins SM, Smith CY, Hieken TJ. Radial scar/complex sclerosing lesions: a clinicopathologic correlation study from a single institution. Ann Diagn Pathol. 19, 24–8 (2015).

Resetkova E, Edelweiss M, Albarracin CT, Yang WT. Management of radial sclerosing lesions of the breast diagnosed using percutaneous vacuum-assisted core needle biopsy: recommendations for excision based on seven years’ of experience at a single institution. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 127, 335–43 (2011).

Farshid G, Buckley E. Meta-analysis of upgrade rates in 3163 radial scars excised after needle core biopsy diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 174, 165–77 (2019).

Kraft E, Limberg JN, Dodelzon K, Newman LA, Simmons R, Swistel A, et al. Radial scars and complex sclerosing lesions of the breast: prevalence of malignancy and natural history under active surveillance. Ann Surg Oncol. 28, 5149–55 (2021).

Nakhlis F, Lester S, Denison C, Wong SM, Mongiu A, Golshan M. Complex sclerosing lesions and radial sclerosing lesions on core needle biopsy: Low risk of carcinoma on excision in cases with clinical and imaging concordance. Breast J. 24, 133–8 (2018).

Foley NM, Racz JM, Al-Hilli Z, Livingstone V, Cil T, Holloway CM, et al. An international multicenter review of the malignancy rate of excised papillomatous breast lesions. Ann Surg Oncol. 22 Suppl 3, S385–90 (2015).

Fu CY, Chen TW, Hong ZJ, Chan DC, Young CY, Chen CJ, et al. Papillary breast lesions diagnosed by core biopsy require complete excision. Eur J Surg Oncol. 38, 1029–35 (2012).

Cyr AE, Novack D, Trinkaus K, Margenthaler JA, Gillanders WE, Eberlein TJ, et al. Are we overtreating papillomas diagnosed on core needle biopsy? Ann Surg Oncol. 18, 946–51 (2011).

Kang HJ, Kwon SY, Kim A, Kim WG, Kim EK, Kim AR, et al. A multicenter study of interobserver variability in pathologic diagnosis of papillary breast lesions on core needle biopsy with WHO classification. J Pathol Transl Med. 55, 380–7 (2021).

NHS Breast Screening Programme Clinical guidance for breast cancer screening assessment [Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/567600/Clinical_guidance_for_breast__cancer_screening__assessment_Nov_2016.pdf.

Chen YA, Mack JA, Karamchandani DM, Zaleski MP, Xu L, Dodge DG, et al. Excision recommended in high-risk patients: Revisiting the diagnosis of papilloma on core biopsy in the context of patient risk. Breast J. 25, 232–6 (2019).

Qiu L, Mais DD, Nicolas M, Nanyes J, Kist K, Nazarullah A. Diagnosis of papillary breast lesions on core needle biopsy: Upgrade rates and interobserver variability. Int J Surg Pathol. 27, 736–43 (2019).

Jakate K, De Brot M, Goldberg F, Muradali D, O’Malley FP, Mulligan AM. Papillary lesions of the breast: impact of breast pathology subspecialization on core biopsy and excision diagnoses. Am J Surg Pathol. 36, 544–51 (2012).

Nasehi L, Sturgis CD, Sharma N, Turk P, Calhoun BC. Breast cancer risk associated with benign intraductal papillomas initially diagnosed on core needle biopsy. Clin Breast Cancer. 18, 468–73 (2018).

Swapp RE, Glazebrook KN, Jones KN, Brandts HM, Reynolds C, Visscher DW, et al. Management of benign intraductal solitary papilloma diagnosed on core needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 20, 1900–5 (2013).

Jaffer S, Bleiweiss IJ, Nagi C. Incidental intraductal papillomas (< 2 mm) of the breast diagnosed on needle core biopsy do not need to be excised. Breast J. 19, 130–3 (2013).

Grimm LJ, Bookhout CE, Bentley RC, Jordan SG, Lawton TJ. Concordant, non-atypical breast papillomas do not require surgical excision: A 10-year multi-institution study and review of the literature. Clin Imaging. 51, 180–5 (2018).

Ma Z, Arciero CA, Styblo TM, Wang H, Cohen MA, Li X. Patients with benign papilloma diagnosed on core biopsies and concordant pathology-radiology findings can be followed: experiences from multi-specialty high-risk breast lesion conferences in an academic center. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 183, 577–84 (2020).

Yamaguchi R, Tanaka M, Tse GM, Yamaguchi M, Terasaki H, Hirai Y, et al. Management of breast papillary lesions diagnosed in ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted and core needle biopsies. Histopathology. 66, 565–76 (2015).

Wyss P, Varga Z, Rossle M, Rageth CJ. Papillary lesions of the breast: outcomes of 156 patients managed without excisional biopsy. Breast J. 20, 394–401 (2014).

Nayak A, Carkaci S, Gilcrease MZ, Liu P, Middleton LP, Bassett RL, Jr., et al. Benign papillomas without atypia diagnosed on core needle biopsy: experience from a single institution and proposed criteria for excision. Clin Breast Cancer. 13, 439–49 (2013).

Bennett LE, Ghate SV, Bentley R, Baker JA. Is surgical excision of core biopsy proven benign papillomas of the breast necessary? Acad Radiol. 17, 553–7 (2010).

Holley SO, Appleton CM, Farria DM, Reichert VC, Warrick J, Allred DC, et al. Pathologic outcomes of nonmalignant papillary breast lesions diagnosed at imaging-guided core needle biopsy. Radiology. 265, 379–84 (2012).

Sohn V, Keylock J, Arthurs Z, Wilson A, Herbert G, Perry J, et al. Breast papillomas in the era of percutaneous needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 14, 2979–84 (2007).

Limberg J, Kucher W, Fasano G, Hoda S, Michaels A, Marti JL. Intraductal papilloma of the breast: prevalence of malignancy and natural history under active surveillance. Ann Surg Oncol. 28, 6032–40 (2021).

Nakhlis F, Baker GM, Pilewskie M, Gelman R, Calvillo KZ, Ludwig K, et al. The incidence of adjacent synchronous invasive carcinoma and/or ductal carcinoma in situ in patients with intraductal papilloma without atypia on core biopsy: Results from a prospective multi-institutional registry (TBCRC 034). Ann Surg Oncol. 28, 2573–8 (2020).

Berg WA, Berg JM, Sickles EA, Burnside ES, Zuley ML, Rosenberg RD, et al. Cancer yield and patterns of follow-up for BI-RADS category 3 after screening mammography recall in the national mammography database. Radiology. 296, 32–41 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The Introduction and Discussion were written jointly by the authors. The sections arguing for immediate surgical excision of high-risk and selected benign lesions were written by AH and HG. The sections proposing nonoperative management of selected patients with high-risk and selected benign lesions were written by BC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Calhoun is a Member of the Oncology Advisory Board for Luminex Corp. Dr. Gilmore is a Consultant for Agendia, Inc. and a Member of the Digital Pathology Advisory Board for Sectra. Dr. Harbhajanka has no financial relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harbhajanka, A., Gilmore, H.L. & Calhoun, B.C. High-risk and selected benign breast lesions diagnosed on core needle biopsy: Evidence for and against immediate surgical excision. Mod Pathol 35, 1500–1508 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-022-01092-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-022-01092-w

This article is cited by

-

SC-Unext: A Lightweight Image Segmentation Model with Cellular Mechanism for Breast Ultrasound Tumor Diagnosis

Journal of Imaging Informatics in Medicine (2024)