Abstract

Despite its superior efficacy, clozapine is helpful in only a subset of patients with schizophrenia unresponsive to other antipsychotics. This lack of complete success has prompted the frequent use of various clozapine combination strategies despite a paucity of evidence from randomized controlled trials supporting their efficacy. Pimozide, a diphenylbutylpiperidine, possesses pharmacological and clinical properties distinct from other typical antipsychotics. An open-label trial of pimozide adjunctive treatment to clozapine provided promising pilot data in support of a larger controlled trial. Therefore, we conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-designed 12-week trial of pimozide adjunctive treatment added to ongoing optimal clozapine treatment in 53 patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder partially or completely unresponsive to clozapine monotherapy. An average dose of 6.48 mg/day of pimozide was found to be no better than placebo in combination with clozapine at reducing Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total, positive, negative, and general psychopathology scores. There is no suggestion from this rigorously conducted trial to suggest that pimozide is an effective augmenting agent if an optimal clozapine trial is ineffective. However, given the lack of evidence to guide clinicians and patients when clozapine does not work well, more controlled trials of innovative strategies are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The introduction of clozapine provided a more effective treatment option for patients with schizophrenia refractory to first generation (Wahlbeck et al, 1999) and second generation (McEvoy et al, 2006) antipsychotic medication. However, only 30–60% of patients with schizophrenia who are unresponsive to ‘typical’ antipsychotics will respond to clozapine (Lieberman et al, 1994; Kane et al, 1988; Breier et al, 1994; Pickar et al, 1992), prompting the frequent use of various clozapine combination strategies despite a paucity of controlled trials demonstrating the clinical usefulness or safety of such strategies.

Indeed, the majority of reports on clozapine combination strategies are case reports and open-label trials. Among the few published controlled trials, the most frequently reported are trials with a second antipsychotic drug. To date, clozapine combination strategies with chlorpromazine (Potter et al, 1989), risperidone (Honer et al, 2006; Anil Ya∂cio∂lu et al, 2005; Freudenreich et al, 2007), and aripiprazole (Fleischhacker et al, 2010) have proven ineffective. The only positive results have been reported with sulpiride (Shiloh et al, 1997) and amisulpiride (Genç et al, 2007); however, significant methodological limitations call these results into question.

Pimozide, a diphenylbutylpiperidine, is generally considered a typical antipsychotic with primarily dopamine D2 receptor-blocking activity (Pinder et al, 1976). However, unlike other typical antipsychotics, pimozide does not block dopamine autoreceptors (Roth, 1994; Walters and Roth, 1976), does not produce D2 receptor upregulation (Tecott et al, 1986), lacks affinity for α-adrenergic receptors (Peroutka et al, 1977), and is a potent opiate receptor antagonist (Creese et al, 1976). Pimozide has also demonstrated particular efficacy in treating monosymptomatic delusional disorder (Riding and Munro 1975; Reilly, 1975; Hamann and Avnstorp, 1982; Johnson and Anton, 1983; Munro et al, 1985).

On the basis of these data and promising pilot data from an open-label trial of pimozide adjunctive treatment to clozapine non-responders (Friedman et al, 1997), we conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled 12-week trial of pimozide adjunctive treatment added to ongoing optimal clozapine treatment in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder partially or completely unresponsive to clozapine monotherapy. The two main hypotheses tested were: (1) that pimozide adjunctive treatment to clozapine would produce a statistically significant greater reduction in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total scores compared with the placebo adjunct and (2) that pimozide adjunctive treatment to clozapine would produce significantly greater reduction in Clinical Global Impression (CGI) score compared with the placebo adjunct.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Participants

Subjects eligible for this study were those with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder based on information obtained from the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (Andreasen et al, 1992) interview. In addition, potential subjects were treatment unresponsive to an optimal trial of clozapine monotherapy. Non-response to treatment was defined as the presence, at 4 consecutive weekly screening phase ratings, of persistent positive psychotic symptoms characterized by PANSS scores of 4 or higher on at least two items from the positive subscale, a PANSS total score >60 and a CGI ⩾4; constructs were adopted from the US multicenter trial of clozapine (Kane et al, 1988).

To ensure optimal trials of clozapine for all prospective subjects, we required a minimum plasma clozapine concentration of 378 ng/ml for a minimum treatment period of 8 weeks before study entry. This cutoff was based on the average of minimum effective plasma concentration values suggested by available studies, which ranges from 350 to 420 ng/ml (Perry et al, 1991; Potkin et al, 1994; Kronig et al, 1995; Hasegawa et al, 1993; Miller et al, 1994). Moreover, although the precise treatment duration required to obtain an optimal response to clozapine remains debated, we based our choice of 8 weeks on the observations of Conley and colleagues (1997).

Subjects were recruited from inpatient and outpatient treatment settings at Mount Sinai Hospital, Pilgrim Psychiatric Center and Manhattan Psychiatric Center in New York following institutional review board approval at these facilities and after informed consent was provided. Following enrollment, the first 4 weeks of the study were used to assess non-response to treatment and stability of symptoms by performing weekly PANSS ratings. Symptom stability was defined as PANSS total score changes < 20% from the first assessment. After demonstrating four weeks of symptom stability, baseline assessments were performed.

Potential subjects were excluded from participation in the study if they were receiving other psychotropic medications in addition to clozapine, with the exception of benzodiazepines, benztropine, and valproic acid. Furthermore, once participants entered the symptom stability-screening phase of the study, no changes to the clozapine dose were permitted, nor was the addition of other psychotropic medication permitted (with the exception of benztropine) for the duration of the study. Participants were also excluded if it was determined that they were abusing alcohol or drugs within the 6-month period preceding study entry as ascertained by history and urine toxicology screen.

Assessments

Severity of positive and negative schizophrenic symptoms was assessed with the PANSS (Kay, 1991). The PANSS contains 30 items, with 7 items rating positive symptoms, 7 rating negative symptoms, and 16 other items assessing ‘general psychopathology’. Ongoing reliability assessments ensured that inter-rater reliability was maintained for all raters above .80 (ICC). Severity of extrapyramidal symptoms was rated with the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS; Chouinard and Ross-Chouinard, 1979). The EPS domains of abnormal involuntary movements, Parkinsonism, dystonias, and akathisia are rated for individual body parts on a two-dimensional continuum of severity and frequency. Given that the increased risk of extrapyramidal symptoms associated with pimozide threatened the integrity of the blind, assignment of assessments ensured that the rating of the ESRS was carried out by personnel different from those performing the PANSS and functional competence ratings. Functional competence was assessed with the Specific Level of Function scale (SLOF; Schneider and Streuening, 1983). The SLOF consists of 43 items rated on a five-point Likert-type scale, grouped into five functional and behavioral areas. These areas include: social skills, problem behaviors, self-care deficits, community living skills, and vocational functioning. In addition, blood pressure, pulse, side effects, and laboratory studies were monitored during the study. In accordance with published reports on the use of pimozide, ECGs were monitored at regular intervals during the course of the study (Shapiro et al, 1983). Manual interpretations of every ECG were done to assess rhythm, waveforms, and intervals, such as QRS, PR, RR, and QT intervals. Because the QT interval shortens with increasing heart rate, the QT interval, corrected for heart rate (QTc), was accomplished by the following commonly used formula (QT/Sqrt(RR); Heger et al, 1987).

Treatment Design

Following baseline assessments, subjects were randomized to double-blind treatment with pimozide or matching placebo in a 1:1 fashion. Following randomization, a 4-week titration period began during which either pimozide or placebo was added to clozapine treatment at a rate of 2 mg/week by a blinded physician to a desired clinical effect or to a maximum dose of 8 mg/day. The maximum dose of pimozide was based on the maximum dose used in our open-label trial with pimozide (Friedman et al, 1997). When, in the opinion of the study physician, an optimal dose of study medication was achieved at the end of the 4-week titration phase, treatment continued with this optimal dose for an additional 8 weeks. Compliance of outpatient subjects with study medication was assessed by weekly pill counts.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was carried out by employing the Generalized Estimation Equation (GEE) method to analyze the efficacy data using independent working correlation. Models: Yij=a+b1groupi+b2weekj+b3groupi × weekj+eij, where Yij=efficacy measurement (ie, PANSS total scores) of ith patients in jth week; groupi=0 if the ith patient receives treatment A, =1 otherwise; weekj=j, j=0, 1, 2,…, 12; eij=error; a=intercept; b1=group effect; b2=time effect; and b3=group × time effect. The model also adjusted for the following confounding factors: (1) baseline PANSS scores, (2) clozapine plasma level, (3) clozapine treatment duration, (4) age, (5) age of onset of illness, (6) treatment setting (inpatient vs outpatient), and (7) race.

RESULTS

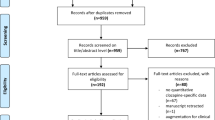

A total of 76 subjects were consented, 16 subjects were excluded during the 4-week symptom stability-screening period before randomization because of withdrawal of consent or a failure to meet inclusion and exclusion criteria. Seven additional subjects were randomized to a haloperidol adjunctive pilot study. A total of 53 subjects were randomized to study drug; 28 to placebo; and 25 to pimozide (see Figure 1). In all, 23 of the 28 subjects randomized to placebo and 22 of the 25 subjects randomized to pimozide completed all 12 weeks of the study. One subject randomized to pimozide withdrew early because of severe EPS, whereas two withdrew early because of adverse events deemed unrelated to study medication (delirium because of an UTI, exacerbation of hemorrhoidal bleeding). In all, 5 of the 28 subjects randomized to placebo withdrew early; two subjects because of persistently severe psychotic symptoms necessitating treatment changes by the treating physician not allowable by the protocol, one because of an episode of bigeminy, one because of hypotension, and one withdrew consent to continue participation (Figure 1).

CONSORT diagram showing the flow of participants through each stage of the Pimozide Study.

Table 1 shows baseline clinical and demographic data for the pimozide and placebo treatment groups. Both groups had similar baseline plasma clozapine levels above the therapeutic threshold. The group randomized to pimozide showed a trend toward lower baseline PANSS total scores. The group randomized to placebo had a greater proportion of Caucasian subjects, whereas the group randomized to pimozide had a greater proportion of African-American subjects (p=0.04). No other differences were noted.

The average daily dose of pimozide utilized during the treatment phase of the study was 6.48 mg/day (SD=2.18). GEE modeling demonstrated no significant treatment by time interaction in favor of pimozide on PANSS total score change over the 12-week study period (p=0.53), PANSS positive score change (p=0.55), PANSS negative score change (p=0.15), PANSS general psycvhopathology score change (p=0.52), nor CGI score change (p=0.15; Figure 2, Table 2). Exploratory analyses showed no significant difference in SLOF subscale change scores between the two treatment groups (Table 2.). Analysis of safety data (Table 2) showed no significant changes in plasma clozapine levels, blood glucose, cholesterol, or triglycerides. There was a modest increase in QTc interval associated with pimozide treatment (mean=9 ms) compared with placebo (mean=−1.5 ms), the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.19). Although there were no significant differences between placebo and pimozide on the change in scores for the Parkinsonism, dystonia, and dyskinesia subscales of the ESRS, there was a trend toward a greater frequency of hypersalivation in the pimozide group compared with the placebo group (32% vs 11%; p=0.09).

Line and symbol plot of weekly means of: (a) PANSS total scores, (b) PANSS positive scores, (c) PANSS negative scores, and (d) PANSS general psychopathology scores for pimozide- and placebo-treated groups.

DISCUSSION

The results of this randomized controlled trial do not support the efficacy of pimozide adjunctive treatment to clozapine in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder unresponsive to clozapine monotherapy. Similar to several other clozapine augmentation trials, the positive results of our initial open-label study (Friedman et al, 1997) were not confirmed in this double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Although moderately sized, it is possible that this investigation was underpowered to demonstrate more modest significant results. However, based on the data from this study, the number of subjects required to detect a treatment difference at an alpha<.05, with 80% power using two-tailed tests would be: (1) 424 for PANSS total, (2) 3,876 for PANSS positive, (3) 130 for PANSS negative, and (4) 1292 for PANSS general psychopathology scores. Even with these sample sizes, the differences for PANSS total, negative, and general psychopathology scores would favor placebo.

The most common shortcoming of the few published controlled trials of clozapine combination treatments is the lack of data demonstrating optimal treatment with clozapine monotherapy before entry into combination treatment studies. An optimal trial requires a minimum therapeutic plasma concentration of clozapine and minimum duration of treatment. Often, therapeutic doses of clozapine are assumed by evaluating dose-effect relationships, with no regard for plasma levels. However, several studies have found very large interindividual variability in plasma concentrations of clozapine at fixed doses (Perry et al, 1991; Potkin et al, 1994; Olesen et al, 1995). Moreover, several studies suggest that a minimum effective plasma concentration from 350 to 420 ng/ml (Perry et al, 1991; Potkin et al, 1994; Kronig et al, 1995; Hasegawa et al, 1993; Miller et al, 1994) is required to ensure optimal clinical response. Both conditions, a minimum period of stable prestudy treatment and a minimum plasma clozapine concentration at baseline and throughout the study, were fulfilled in our study.

Clinicians need to consider the issue of an optimal clozapine monotherapy trial when interpreting the positive results of unreplicated studies with clozapine-augmenting agents, such as sulpiride (Shiloh et al, 1997), amisulpiride (Genç et al, 2007), and risperidone (Josiassen et al, 2005). Although these studies demonstrated significant improvement in schizophrenia symptoms with these combination treatments compared with clozapine treatment alone (Shiloh et al, 1997; Josiassen et al, 2005) and clozapine combined with quetiapine (Genç et al, 2007), neither baseline nor follow-up clozapine plasma concentrations were reported. Therefore, it is possible that one or both treatment groups did not have, on average, therapeutic clozapine levels at baseline, and/or experienced pharmacokinetic interactions with the study drug, elevating clozapine plasma concentrations. These factors may have significantly confounded the results of these studies. Indeed, when baseline clozapine concentrations were demonstrated to be similar and above minimum therapeutic concentration thresholds for both treatment groups, the risperidone plus clozapine combination was shown not to be superior to clozapine alone in a rigorous double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted by Honer et al (2006). Moreover, two additional studies failed to replicate the positive results of the first risperidone augmentation trial (Anil Ya∂cio∂lu et al, 2005; Freudenreich et al, 2007).

In addition to the data on lack of efficacy of the combination treatments that these trials provide, clinicians should consider the safety data reported by these studies. For example, the risperidone plus clozapine combination demonstrated a tendency toward increasing fasting glucose levels (Honer et al, 2006), and producing greater levels of sedation, akathisia, and prolactin elevations (Anil Ya∂cio∂lu et al, 2005) when compared with clozapine monotherapy. Potential side effects of these combinations should factor into the clinician's decision to engage in such treatment strategies, especially when data supporting their efficacy is tenuous or absent.

However, even before clinicians consider any clozapine combination strategy, an optimal clozapine trial should be ensured as was done in this trial. In those cases where side effects limit the clinician's ability to attain therapeutic plasma concentrations, these should be addressed before initiating a combination strategy. Only after these issues have been addressed should the clinician consider clozapine augmentation strategies as the next step to improve response. However, there is no suggestion from this rigorously conducted trial that pimozide is an effective augmenting agent if an optimal clozapine trial is ineffective. Therefore, given the continued lack of evidence to guide clinicians and patients when clozapine does not work well, more controlled trials of innovative strategies are warranted.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders (4th edn) Washington DC.

Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Arndt S (1992). The comprehensive assessment of symptoms and history (CASH): an instrument for assessing psychopathology and diagnosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49: 615–623.

Anil Ya∂cio∂lu AE, Kivircik Akdede BB, Turgut TI, Tümüklü M, Yazici MK, Alptekin K, Ertuǧrul A, Jayathilake K, Göǧüş A, Tunca Z, Meltzer HY (2005). A double-blind controlled study of adjunctive treatment with risperidone in schizophrenic patients partially responsive to clozapine: efficacy and safety. J Clin Psychiatry 66: 63–72.

Breier A, Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, Davis OR, Irish D, Summerfelt A, Carpenter Jr WT (1994). Effects of clozapine on positive and negative symptoms in outpatients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 151: 20–26.

Chouinard G, Ross-Chouinard A, Annable L, Jones B (1980). The extrapyramidal symptom rating scale. Can J Neurol Sci 7: 233.

Conley RR, Carpenter WT Jr, Tamminga CA (1997). Time to clozapine response in a standardized trial. Am J Psychiatry 154: 1243–1247.

Creese I, Feinberg AP, Snyder SH (1976). Butyrphenone influence on the opiate receptor. Eur J Pharmacol 36: 231–235.

Fleischhacker WW, Heikkinen ME, Olié JP, Landsberg W, Dewaele P, McQuade RD et al (2010). Effects of adjunctive treatment with aripiprazole on body weight and clinical efficacy in schizophrenia patients treated with clozapine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 13: 1115–1125.

Freudenreich O, Henderson DC, Walsh JP, Culhane MA, Goff DC (2007). Risperidone augmentation for schizophrenia partially responsive to clozapine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr Res 92: 90–94.

Friedman J, Ault K, Powchik P (1997). Pimozide augmentation for the treatment of schizophrenic patients who are partial responders to clozapine. Biol Psychiatry 42: 522–523.

Genç Y, Taner E, Candansayar S (2007). Comparison of clozapine-amisulpride and clozapine-quetiapine combinations for patients with schizophrenia who are partially responsive to clozapine: a single-blind randomized study. Adv Ther 24: 1–13.

Hamann K, Avnstorp C (1982). Delusions of infestation treated by pimozide: a double-blind crossover clinical study. Acta Derm Venereol 62: 55–58.

Hasegawa M, Gutierrez-Esteinou R, Way L, Meltzer HY (1993). Relationship between clinical efficacy and clozapine concentrations in plasma in schizophrenia: effect of smoking. J Clin Psychopharmacol 13: 383–390.

Heger JW, Niemann JT, Criley JM (1987). Cardiology for the House Officer: Second Edition Copyright 1987 Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore MD.

Honer WG, Thornton AE, Chen EY, Chan RC, Wong JO, Bergmann A et al (2006). Clozapine alone versus clozapine and risperidone with refractory schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 354: 472–482.

Johnson GC, Anton RF (1983). Pimozide in delusions of parasitosis. J Clin Psychiatry 44: 233.

Josiassen RC, Joseph A, Kohegyi E, Stokes S, Dadvand M, Paing WW et al (2005). Clozapine augmented with risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 162: 130–136.

Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H (1988). Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 45: 789–796.

Kay (1991). Positive and Negative Syndromes in Schizophrenia. Brunner/Mazel: New York.

Kronig MH, Munne RA, Szymanski S, Safferman AZ, Pollack S, Cooper T et al (1995). Plasma clozapine levels and clinical response for treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 152: 179–182.

Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, Pollack S, Szymanski S, Johns C, Howard A et al (1994). Clinical effects of clozapine in chronic schizophrenia: response to treatment and predictors of outcome. Am J Psychiatry 151: 1744–1752.

McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, Davis SM, Meltzer HY, Rosenheck RA, et al, CATIE Investigators (2006). Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry 163: 600–610.

Miller DD, Fleming F, Holman TL, Perry PJ (1994). Plasma clozapine concentrations as a predictor of clinical response: a follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry 55: 117–121.

Munro A, O’Brien JV, Ross D (1985). Two cases of ‘pure’ or ‘primary’ erotomania successfully treated with pimozide. Can J Psychiatry 30: 619–622.

Olesen OV, Thomsen K, Jensen PN, Wulff CH, Rasmussen NA, Refshammer C (1995). Clozapine serum levels and side effects during steady state treatment of schizophrenic patients: a cross-sectional study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 117: 371–378.

Peroutka SJ, U′Prichard DC, Greenberg DA, Snyder SH (1977). Neuroleptic drug interactions with norepinephrine alpha receptor binding sites in rat brain. Neuropharmacology 16: 549–556.

Perry PJ, Miller DD, Arndt SV, Cadoret RJ (1991). Clozapine and norclozapine plasma concentrations and clinical response of treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 148: 231–235.

Pickar D, Owen RR, Litman RE, Konicki E, Gutierrez R, Rapaport MH (1992). Clinical and biologic response to clozapine in patients with schizophrenia. Crossover comparison with fluphenazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49: 345–353.

Pinder RM, Brogden RN, Swayer R, Speight TM, Spencer R, Avery GS (1976). Pimozide: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic uses in psychiatry. Drugs 12: 1–40.

Potkin SG, Bera R, Gulasekaram B, Costa J, Hayes S, Jin Y et al (1994). Plasma clozapine concentrations predict clinical response in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 55: 133–136.

Potter WZ, Ko GN, Zhang LD, Yan WW (1989). Clozapine in China: a review and preview of US/PRC collaboration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 99: S87–S91.

Reilly TM (1975). Letter: pimozide in monosymptomatic psychosis. Lancet 7921: 1385–1386.

Riding BE, Munro A (1975). Letter: pimozide in monosymptomatic psychosis. Lancet 7903: 400–401.

Roth RH (1994). Dopamine autoreceptors: pharmacology, function and comparison with post-synaptic dopamine receptors. Commun Psychopharmacol 3: 429–433.

Schneider LC, Streuening EL (1983). SLOF: a behavioral rating scale for assessing the mentally ill. Soc Work Res Abstr 6: 9–21.

Shapiro AK, Shapiro E, Eisenkraft GJ (1983). Treatment of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome with pimozide. Am J Psychiatry 140: 1183–1186.

Shiloh R, Zemishlany Z, Aizenberg D, Weizman A (1997). Sulpiride adjunction to clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients: a preliminary case series study. Eur Psychiatry 12: 152–155.

Tecott LH, Kwong LL, Uhr S, Peroutka S (1986). Differential modulation of dopamine D2 receptors by chronic haloperidol, nitrendipine and pimozide. Biol Psychiatry 21: 1114–1122.

Wahlbeck K, Cheine M, Essali A, Adams C (1999). Evidence of clozapine's effectiveness in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry 156: 990–999.

Walters JR, Roth RH (1976). Dopaminergic neurons: an in vivo system for measuring drug interactions with presynaptic receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 296: 5–14.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant number MH067806-01A2 awarded by the NIMH to Dr Joseph I Friedman.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Jean-Pierre Lindenmayer has received grant support from Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Otsuka, and Dainippon-Sumitomo. Lindenmayer has served as a consultant to Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Shire Pharmaceuticals. Frances Alcantara has received grant support from Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Dainippon-Sumitomo, and Otsuka. Parak Mohan has received grant support from Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Dainippon-Sumitomo, and Otsuka. Adel Iskander has received grant support from Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Dainippon-Sumitomo, and Otsuka. David Adler has received speaker honoraria from Eli Lilly and Company. He is currently employed as a research psychiatrist by Neurobehavioral Research (Cedarhurst, NY). Philip D Harvey has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly and Company, Merck and Company, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, and Dainippon-Sumitomo America. He has grant support from AstraZeneca. Kenneth L Davis's wife receives royalty income from Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Shire Pharmaceuticals from the sale of a patented drug for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. The remaining authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Additional information

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00158223

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Friedman, J., Lindenmayer, JP., Alcantara, F. et al. Pimozide Augmentation of Clozapine Inpatients with Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorder Unresponsive to Clozapine Monotherapy. Neuropsychopharmacol 36, 1289–1295 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2011.14

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2011.14

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

STF-62247 and pimozide induce autophagy and autophagic cell death in mouse embryonic fibroblasts

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

A randomized double-blind controlled trial to assess the benefits of amisulpride and olanzapine combination treatment versus each monotherapy in acutely ill schizophrenia patients (COMBINE): methods and design

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2020)

-

Loperamide, pimozide, and STF-62247 trigger autophagy-dependent cell death in glioblastoma cells

Cell Death & Disease (2018)