Abstract

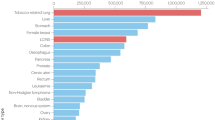

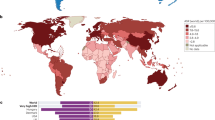

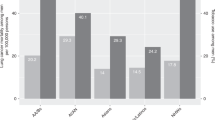

Lung carcinoma is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer deaths in the US. It accounts for 12% of all cancers diagnosed worldwide, making it the most common malignancy, other than nonmelanoma skin cancer. A new focus has emerged involving the role of race and ethnicity in lung carcinoma. Current health statistics data demonstrate striking disparities, which are most evident between African American patients and their white counterparts. This disparity is greatest among male patients, where statistically significant differences are seen not only in lung cancer incidence and risk, but also in survival and treatment outcomes. Several hypotheses that attempt to explain this disparity include genetic, cultural and socioeconomic differences, in addition to differences in tobacco use and exposure. Current evidence does not clearly identify the reasons for this observed disparity, or the role the aforementioned factors play in the development and overall outcomes of people with lung cancer in these populations. This disease continues to pose a considerable public health burden and more research is needed to improve understanding of the disparity of lung carcinoma statistics among African Americans. This review summarizes the existing body of knowledge regarding lung carcinoma in African Americans and attempts to identify promising areas for future investigation and intervention.

Key Points

-

US health statistics indicate a racial disparity of lung carcinoma in terms of risks, management, and outcomes, which is most striking in African Americans compared with their white counterparts

-

Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain the disparity between ethnic groups, including differences in tobacco exposure, genetic susceptibility, culture, and socioeconomics, but no single factor has been able to account for it

-

This disparity has led to increased mortality and lower survival rates in African Americans compared with their white counterparts

-

Despite a lack of clear evidence that genetic and proteomic alterations have any significant role in lung carcinoma in African Americans, evidence exists that race-specific gene mutations in EGFR are associated with improved responses to therapy

-

Most investigations and interventions have focused on strategies to improve health care access and use, but more studies are needed to understand the genetic polymorphisms in African Americans that influence risk, susceptibility to exposure, and treatment outcomes in lung carcinoma

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ries LAG et al. (eds) (online 2006) SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2003. National Cancer Institute. [http://seer.cancer.gov/faststats/sites.php?stat=Incidence&site=Lung+and+Bronchus+Cancer&x=9&y=18] (accessed 1 January 2007)

Stewart JH (2001) Lung carcinoma in African Americans. Cancer 91: 2476–2482

Higgins RS et al. (2003) Lung cancer in African-Americans. Ann Thorac Surg 76 (Suppl): S1363–S1366

Alberg AJ et al. (2005) Epidemiology of lung cancer: looking to the future. J Clin Oncol 23: 3175–3185

Cooley ME and Jennings-Dozier K (1998) Lung cancer in African-Americans. A call for action. Cancer Pract 6: 99–106

Gadgeel SM et al. (2001) Impact of race in lung cancer: analysis of temporal trends from a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Chest 120: 55–63

Schwartz AG and Swanson GM (1997) Lung carcinoma in African-Americans and whites: a population based study in metropolitan Detroit, Michigan. Cancer 79: 45–52

Schrek R et al. (1950) Tobacco smoking as an etiologic factor in disease. Cancer Res 10: 49–58

Mills CA and Porter MM (1950) Tobacco smoking habits, and cancer of the mouth and respiratory system. Cancer Res 10: 539–542

Wynder EL and Graham EA (1950) Tobacco smoking as a possible etiologic factor in bronchiogenic carcinoma; a study of six hundred and eighty-four proved cases. J Am Med Assoc 143: 329–336

Levin ML et al. (1950) Cancer and tobacco smoking; a preliminary report. J Am Med Assoc 143: 336–338

Doll R and Hill AB (1950) Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; a preliminary report. BMJ 2: 739–748

Cote ML et al. (2005) Risk of lung cancer among white and black relatives of individuals with early-onset lung cancer. JAMA 293: 3036–304

Thun MJ et al. (2002) Tobacco use and cancer: an epidemiologic perspective for geneticists. Oncogene 21: 7307–7325

Vineis P et al. (2004) Tobacco and cancer: recent epidemiological evidence. J Natl Cancer Inst 96: 99–106

Doll R et al. (2004) Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observation on male British doctors. BMJ 328: 1519–1533

Schiller JS et al. (2005) Early release of selected estimates based on data from the January–June 2005 National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics [http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm] (accessed 2 February 2006)

Giovino GA et al. (2004) Epidemiology of menthol cigarette use. Nicotine Tob Res 6: S67–S81

Sidney S et al. (1989) Mentholated cigarette use among multiphasic examinees 1979–1986. Am J Public Health 79: 1415–1416

Ahijevych K and Garrett BE (2004) Menthol pharmacology and its potential impact on cigarette smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res 6 (Suppl): S17–S28

Caraballo RS et al. (1998) Racial and ethnic differences in serum cotinine levels of cigarette smokers: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991. JAMA 280: 135–139

Gardiner PS (2004) The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res 6 (Suppl): S55–S65

Brooks DR et al. (2003) Menthol cigarettes and risk of lung cancer. Am J Epidemiol 158: 609–616

Muscat JE et al. (2002) Mentholated cigarettes and smoking habits in whites and blacks. Tob Control 11: 368–371

Sidney S et al. (1995) Mentholated cigarette use and lung cancer. Arch Intern Med 155: 727–732

Haiman CA et al. (2006) Ethnic and racial differences in the smoking-related risk of lung cancer. N Engl J Med 354: 333–342

Keith RL and Miller YE (2005) Lung cancer: genetics of risk and advances in chemoprevention. Curr Opin Pulm Med 11: 265–271

Salgia R and Skarin AT (1998) Molecular abnormalities in lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 16: 1207–1217

Wrensch MR et al. (2005) CYP1A1 variants and smoking-related lung cancer in San Francisco Bay Area Latinos and African-Americans. Int J Cancer 113: 141–147

Mohr LC et al. (2003) Glutathione S-transferase M1 polymorphism and the risk of lung cancer. Anticancer Res 23 (3A): 2111–2124

Cauchi S et al. (2003) Structure and polymorphisms of human aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor (AhRR) gene in a French population: relationship with CYP1A1 inducibility and lung cancer. Pharmacogenetics 13: 339–347

Stücker I et al. (2000) Relation between inducibility of CYP1A1, GSTM1 and lung cancer in a French population. Pharmacogenetics 10: 617–627

Miller DP et al. (2003) Smoking and the risk of lung cancer-susceptibility with the GSTP-1 polymorphisms. Epidemiology 14: 545–551

Crofts F et al. (1993) A novel CYP1A1 gene polymorphism in African-Americans. Carcinogenesis 14: 1729–1731

Kelsey KT et al. (1994) A race-specific genetic polymorphism in the CYP1A1 gene is not associated with lung cancer in African-Americans. Carcinogenesis 15: 1121–1124

Taioli E et al. (1998) Lung cancer risk and CYP1A1 genotype in African-Americans. Carcinogenesis 19: 813–817

Taioli E et al. (1995) A specific African-American CYP1A1 polymorphism is associated with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Cancer Res 55: 472–473

London SJ et al. (1995) Lung cancer risk in African-Americans in relations to a race-specific CYP1A1 polymorphism. Cancer Res 55: 6035–6037

Ishibe N et al. (1997) Susceptibility to lung cancer in light smokers associated with CYP1A1 polymorphism in Mexican and African-Americans. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 6: 1075–1080

Tang YM et al. (2000) Human CY1B1 Leu432 Val gene polymorphism: ethnic distribution in African-Americans, Caucasians and Chinese; oestradiol hydroxylase activity; and prostate cancer case and controls. Pharmacogenetics 10: 761–766

Wenzlaff AS et al. (2005) CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 polymorphisms and risk of lung cancer among never smokers: a population-based study. Carcinogenesis 26: 2207–2212

London SJ et al. (1996) Lung cancer risk in relation to the CYP2C9*1/CYP2C9*2 genetic polymorphism among African-Americans and Caucasians in Los Angeles County, California. Pharmacogenetics 6: 527–533

London SJ et al. (1997) Genetic polymorphism of CDP2D6 and lung cancer risk in African-Americans and Caucasians in Los Angeles California. Carcinogenesis 8: 1203–1214

Wu X et al. (1997) Associations between cytochrome P4502E1 genotype, mutagen sensitivity, cigarette smoking and susceptibility to lung cancer. Carcinogenesis 18: 967–973

Wu X et al. (1998) Cytochrome P450 2E1 DraI polymorphisms in lung cancer in minority populations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 7: 13–18

Ford JG et al. (2000) Glutathione S-transferase M1 polymorphism and lung cancer risk in African-Americans. Carcinogenesis 21: 1971–1975

Cote ML et al. (2005) Combinations of glutathione S-transferase genotypes and risk of early-onset lung cancer in Caucasian and African Americans: a population based study. Carcinogenesis 26: 811–819

Park JY et al. (2005) Genetic analysis of microsomal epoxide hydrolase gene and its association with lung cancer risk. Eur J Cancer Prev 14: 223–230

Wu X et al. (2002) p53 genotypes and haplotypes associated with lung cancer susceptibility and ethnicity. J Natl Cancer Inst 94: 681–690

Nakamura H et al. (2006) Survival impact of epidermal growth factor receptor overexpression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Thorax 61: 140–145

Kobayahsi S et al. (2005) Brief report: EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 352: 786–792

Thatcher N et al. (2005) Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small cell lung cancer: results from a randomized, placebo controlled, multicenter study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer). Lancet 366: 1527–1537

Shepherd FA et al. (2004) A randomized placebo-controlled trial of erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small lung cancer (NSCLC) following failure of first and second line chemotherapy. A National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCIC CTG) trial [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 22 (Suppl 1): 14S a7022

Tsao MS et al. (2005) Erlotinib in lung cancer—molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med 353: 133–144

Greenwald HP et al. (1998) Social factors, treatment and survival in early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Public Health 88: 1681–1684

Schneider EC et al. (2002) racial disparities in the quality of care for enrollees in medicare managed care. JAMA 287: 1288–1294

Bach PB et al. (2004) Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med 351: 575–584

Trauth JM et al. (2005) Factors affecting older African American women's decisions to join the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial. J Clin Oncol 23: 8730–8738

Stallings FL et al. (2000) Black participation in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial. Control Clin Trials 21 (Suppl): S379–S389

Shavers VL and Brown ML (2002) Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 94: 334–357

Bach PB et al. (1999) Racial differences in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. N Engl J Med 341: 1198–1205

Lathan CS et al. (2006) The effect of race on invasive staging and surgery in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 24: 413–418

Margolis ML et al. (2003) Racial differences pertaining to a belief about lung cancer surgery. Results of multi-center survey. Ann Intern Med 139: 558–563

Gordon NH et al. (1992) Socioeconomical factors and race in breast cancer recurrence and survival. Am J Epidemiol 135: 609–618

McCann J et al. (2005) Evaluation of the causes for racial disparity in surgical treatment of early stage lung cancer. Chest 128: 3440–3446

Cykert S and Phifer N (2003) Surgical decisions for early stage, non-small cell lung cancer: which racially sensitive perceptions of cancer are likely to explain racial variations in surgery? Med Decis Making 23: 167–176

Rapp E et al. (1988) Chemotherapy can prolong survival in patients with advanced non small lung cancer: report of a Canadian multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 6: 633–641

Stanley KE (1980) Prognostic factors for survival in patients with inoperable lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 65: 25–32

Blackstock AW et al. (2002) Outcomes among African-American/Non-African-American patients with advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma: report from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Natl Cancer Inst 94: 284–290

Blackstock AW et al. (2006) Similar outcomes between African-American and Non-African American patients with extensive-stage small cell lung carcinoma: report from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol 24: 407–412

Murthy VH et al. (2004) Participation in cancer clinical trials: race, age, and age-based disparities. JAMA 291: 2720–2726

Du W et al. (2003) Cost-effectiveness and lung cancer clinical trials. Cancer 98: 1491–1496

McCaskill-Stevens W et al. (1999) Recruiting minority cancer patients into cancer clinical trials: a pilot project involving the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group and the National Medical Association. J Clin Oncol 17: 1029–1039

Adams-Campbell LL et al. (2004) Enrollment of African Americans onto clinical treatment trials: study design barriers. J Clin Oncol 22: 730–734

Pinto HA et al. (2000) Physician perspectives on increasing minorities in cancer clinical trials: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Initiative. Ann Epidemiol 10: S78–S84

Non-small Cell Cancer Lung Cancer Collaborative Group (1995) Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomized clinical trials. BMJ 311: 899–909

Brawley OW (2002) Lung cancer and race: equal treatment yields equal outcomes among equal patients, but there is no equal treatment. J Clin Oncol 24: 332–333

Acknowledgements

R Salgia is supported by NIH/National Cancer Institute – R01 award (R01 CA100750-01A1), Mesothelioma Applied Research Foundation (MARF), American Cancer Society Award (National), and Institutional Cancer Research Awards from the University of Chicago Cancer Center with the American Cancer Society and the V-Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abidoye, O., Ferguson, M. & Salgia, R. Lung carcinoma in African Americans. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 4, 118–129 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncponc0718

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncponc0718

This article is cited by

-

Role of PAX8 in the regulation of MET and RON receptor tyrosine kinases in non-small cell lung cancer

BMC Cancer (2014)

-

Effects of Patient-Provider Race Concordance and Smoking Status on Lung Cancer Risk Perception Accuracy Among African-Americans

Annals of Behavioral Medicine (2013)

-

PAX5 is expressed in small-cell lung cancer and positively regulates c-Met transcription

Laboratory Investigation (2009)

-

Development of a Culturally Targeted Smoking Cessation Intervention for African American Smokers

Journal of Community Health (2009)

-

The role of tobacco in cancer health disparities

Current Oncology Reports (2009)