Abstract

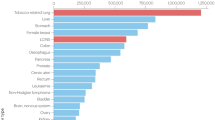

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. However, lung cancer incidence and mortality rates differ substantially across the world, reflecting varying patterns of tobacco smoking, exposure to environmental risk factors and genetics. Tobacco smoking is the leading risk factor for lung cancer. Lung cancer incidence largely reflects trends in smoking patterns, which generally vary by sex and economic development. For this reason, tobacco control campaigns are a central part of global strategies designed to reduce lung cancer mortality. Environmental and occupational lung cancer risk factors, such as unprocessed biomass fuels, asbestos, arsenic and radon, can also contribute to lung cancer incidence in certain parts of the world. Over the past decade, large-cohort clinical studies have established that low-dose CT screening reduces lung cancer mortality, largely owing to increased diagnosis and treatment at earlier disease stages. These data have led to recommendations that individuals with a high risk of lung cancer undergo screening in several economically developed countries and increased implementation of screening worldwide. In this Review, we provide an overview of the global epidemiology of lung cancer. Lung cancer risk factors and global risk reduction efforts are also discussed. Finally, we summarize lung cancer screening policies and their implementation worldwide.

Key points

-

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death globally, with incidence and mortality trends varying greatly by country and largely reflecting differences in tobacco smoking trends.

-

Cigarette smoking is the most prevalent lung cancer risk factor, although environmental exposures, such as biomass fuels, asbestos, arsenic and radon, are all important lung factor risk factors with levels of exposure that vary widely across the globe.

-

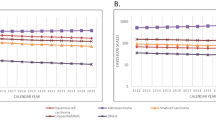

Lung cancer incidence and mortality rates are highest in economically developed countries in which tobacco smoking peaked several decades ago, although these rates have mostly now peaked and are declining.

-

Reductions in lung cancer mortality in economically developed countries reflect decreased incidence (mirroring declines in tobacco smoking) and improvements in treatment of patients with advanced-stage disease, including immunotherapies and targeted therapies.

-

In low-income and middle-income countries at the later stages of the tobacco epidemic, both lung cancer incidence and mortality are increasing, thus highlighting the importance of tobacco mitigation policies for reducing the global burden of lung cancer.

-

Low-dose CT-based lung cancer screening reduces lung cancer mortality, although adoption of lung cancer screening programmes has been slow, with limited uptake compared with other cancer screening programmes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Travis, W. D., Brambilla, E., Burke, A. P., Marx, A. & Nicholson, A. G. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart (IARC, 2015).

Schabath, M. B. & Cote, M. L. Cancer progress and priorities: lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 28, 1563–1579 (2019).

Lortet-Tieulent, J. et al. International trends in lung cancer incidence by histological subtype: adenocarcinoma stabilizing in men but still increasing in women. Lung Cancer 84, 13–22 (2014).

Wakelee, H. A. et al. Lung cancer incidence in never smokers. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 472–478 (2007).

United Nations Development Programme. Human development report 2021-22. UNDP http://report.hdr.undp.org (2022).

Jemal, A., Ma, J., Rosenberg, P. S., Siegel, R. & Anderson, W. F. Increasing lung cancer death rates among young women in southern and midwestern states. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 2739–2744 (2012).

Jemal, A. et al. Higher lung cancer incidence in young women than young men in the united states. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1999–2009 (2018).

Islami, F. et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United states. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 31–54 (2018).

Siegel, D. A., Fedewa, S. A., Henley, S. J., Pollack, L. A. & Jemal, A. Proportion of never smokers among men and women with lung cancer in 7 US states. JAMA Oncol. 7, 302–304 (2021).

Sakoda, L. C. et al. Trends in smoking-specific lung cancer incidence rates within a US integrated health system, 2007-2018. Chest https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2023.03.016 (2023).

Pelosof, L. et al. Proportion of never-smoker non-small cell lung cancer patients at three diverse institutions. J. Natl Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djw295 (2017).

Meza, R., Meernik, C., Jeon, J. & Cote, M. L. Lung cancer incidence trends by gender, race and histology in the United States, 1973-2010. PLoS ONE 10, e0121323 (2015).

Haiman, C. A. et al. Ethnic and racial differences in the smoking-related risk of lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 333–342 (2006).

Murphy, S. E. Biochemistry of nicotine metabolism and its relevance to lung cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100722 (2021).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 7–33 (2021).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72, 7–33 (2022).

Howlader, N. et al. The effect of advances in lung-cancer treatment on population mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 640–649 (2020).

Singh, G. K. & Jemal, A. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival in the United States, 1950-2014: over six decades of changing patterns and widening inequalities. J. Environ. Public Health 2017, 2819372 (2017).

Blom, E. F., Ten Haaf, K., Arenberg, D. A. & de Koning, H. J. Disparities in receiving guideline-concordant treatment for lung cancer in the United States. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 17, 186–194 (2020).

Sineshaw, H. M. et al. County-level variations in receipt of surgery for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer in the United States. Chest 157, 212–222 (2020).

GBD 2019 Tobacco Collaborators. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 397, 2337–2360 (2021).

Allemani, C. et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet 391, 1023–1075 (2018).

Jani, C. et al. Lung cancer mortality in Europe and the USA between 2000 and 2017: an observational analysis. ERJ Open. Res. https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00311-2021 (2021).

Malvezzi, M. et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2023 with focus on lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 34, 410–419 (2023).

Carioli, G. et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2020 with a focus on prostate cancer. Ann. Oncol. 31, 650–658 (2020).

Alves, L., Bastos, J. & Lunet, N. Trends in lung cancer mortality in Portugal (1955-2005). Rev. Port. Pneumol. 15, 575–587 (2009).

Martínez, C., Guydish, J., Robinson, G., Martínez-Sánchez, J. M. & Fernández, E. Assessment of the smoke-free outdoor regulation in the WHO European region. Prev. Med. 64, 37–40 (2014).

Forsea, A. M. Cancer registries in Europe – going forward is the only option. Ecancermedicalscience 10, 641 (2016).

Cho, B. C. et al. Genomic landscape of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in East Asia using circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in clinical practice. Curr. Oncol. 29, 2154–2164 (2022).

Mathias, C. et al. Lung cancer in Brazil. J. Thorac. Oncol. 15, 170–175 (2020).

Souza, M. C., Vasconcelos, A. G. & Cruz, O. G. Trends in lung cancer mortality in Brazil from the 1980s into the early 21st century: age-period-cohort analysis. Cad. Saude Publica 28, 21–30 (2012).

Jiang, D. et al. Trends in cancer mortality in China from 2004 to 2018: a nationwide longitudinal study. Cancer Commun. 41, 1024–1036 (2021).

Parascandola, M. & Xiao, L. Tobacco and the lung cancer epidemic in China. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 8, S21–S30 (2019).

Hosgood, H. D. 3rd et al. In-home coal and wood use and lung cancer risk: a pooled analysis of the International Lung Cancer Consortium. Env. Health Perspect. 118, 1743–1747 (2010).

Kurmi, O. P., Arya, P. H., Lam, K. B., Sorahan, T. & Ayres, J. G. Lung cancer risk and solid fuel smoke exposure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 40, 1228–1237 (2012).

Qiu, A. Y., Leng, S., McCormack, M., Peden, D. B. & Sood, A. Lung effects of household air pollution. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 10, 2807–2819 (2022).

Zhang, M. et al. Trends in smoking prevalence in urban and rural China, 2007 to 2018: findings from 5 consecutive nationally representative cross-sectional surveys. PLoS Med. 19, e1004064 (2022).

Pineros, M., Znaor, A., Mery, L. & Bray, F. A global cancer surveillance framework within noncommunicable disease surveillance: making the case for population-based cancer registries. Epidemiol. Rev. 39, 161–169 (2017).

Wei, W. et al. Cancer registration in China and its role in cancer prevention and control. Lancet Oncol. 21, e342–e349 (2020).

Mathur, P. et al. Cancer statistics, 2020: report from National Cancer Registry Programme, India. JCO Glob. Oncol. 6, 1063–1075 (2020).

Nath, A., Sathishkumar, K., Das, P., Sudarshan, K. L. & Mathur, P. A clinicoepidemiological profile of lung cancers in India – results from the National Cancer Registry Programme. Indian J. Med. Res. 155, 264–272 (2022).

Singh, N. et al. Lung cancer in India. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 1250–1266 (2021).

Kaur, H. et al. Evolving epidemiology of lung cancer in India: reducing non-small cell lung cancer–not otherwise specified and quantifying tobacco smoke exposure are the key. Indian J. Cancer 54, 285–290 (2017).

Mohan, A. et al. Clinical profile of lung cancer in North India: a 10-year analysis of 1862 patients from a tertiary care center. Lung India 37, 190–197 (2020).

Shaikh, R., Janssen, F. & Vogt, T. The progression of the tobacco epidemic in India on the national and regional level, 1998-2016. BMC Public Health 22, 317 (2022).

India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Cancer Collaborators. The burden of cancers and their variations across the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. Lancet Oncol. 19, 1289–1306 (2022).

& Piñeros, M. et al. An updated profile of the cancer burden, patterns and trends in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 13, 100294 (2022).

Raez, L. E. et al. The burden of lung cancer in Latin-America and challenges in the access to genomic profiling, immunotherapy and targeted treatments. Lung Cancer 119, 7–13 (2018).

Pakzad, R., Mohammadian-Hafshejani, A., Ghoncheh, M., Pakzad, I. & Salehiniya, H. The incidence and mortality of lung cancer and their relationship to development in Asia. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 4, 763–774 (2015).

Hamdi, Y. et al. Cancer in Africa: the untold story. Front. Oncol. 11, 650117 (2021).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What are the risk factors for lung cancer? CDC https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/basic_info/risk_factors.htm (2022).

Peto, R. et al. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. Br. Med. J. 321, 323–329 (2000).

Boffetta, P. et al. Cigar and pipe smoking and lung cancer risk: a multicenter study from Europe. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 91, 697–701 (1999).

Pednekar, M. S., Gupta, P. C., Yeole, B. B. & Hébert, J. R. Association of tobacco habits, including bidi smoking, with overall and site-specific cancer incidence: results from the Mumbai cohort study. Cancer Causes Control. 22, 859–868 (2011).

Proctor, R. N. The history of the discovery of the cigarette–lung cancer link: evidentiary traditions, corporate denial, global toll. Tob. Control. 21, 87–91 (2012).

Doll, R. & Hill, A. B. The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits. Br. Med. J. 1, 1451 (1954).

US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Smoking and health: report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service (US Public Health Service, 1964).

Brawley, O. W., Glynn, T. J., Khuri, F. R., Wender, R. C. & Seffrin, J. R. The first Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health: the 50th anniversary. CA Cancer J. Clin. 64, 5–8 (2014).

WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. 2021 global progress report on implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC, 2022).

Oberg, M., Jaakkola, M. S., Woodward, A., Peruga, A. & Prüss-Ustün, A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet 377, 139–146 (2011).

Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: a Report of the Surgeon General (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006).

Yousuf, H. et al. Estimated worldwide mortality attributed to secondhand tobacco smoke exposure, 1990-2016. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e201177 (2020).

Bracken-Clarke, D. et al. Vaping and lung cancer – a review of current data and recommendations. Lung Cancer 153, 11–20 (2021).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in tobacco use among youth. CDC https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/trends-in-tobacco-use-among-youth.html (2022).

Sindelar, J. L. Regulating vaping – policies, possibilities, and perils. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, e54 (2020).

Campus, B., Fafard, P., St Pierre, J. & Hoffman, S. J. Comparing the regulation and incentivization of e-cigarettes across 97 countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 291, 114187 (2021).

Bruce, N. et al. Does household use of biomass fuel cause lung cancer? A systematic review and evaluation of the evidence for the GBD 2010 study. Thorax 70, 433–441 (2015).

Woolley, K. E. et al. Effectiveness of interventions to reduce household air pollution from solid biomass fuels and improve maternal and child health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review protocol. Syst. Rev. 10, 33 (2021).

Johnston, F. H. et al. Estimated global mortality attributable to smoke from landscape fires. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 695–701 (2012).

Korsiak, J. et al. Long-term exposure to wildfires and cancer incidence in Canada: a population-based observational cohort study. Lancet Planet. Health 6, e400–e409 (2022).

Rousseau, M.-C., Straif, K. & Siemiatycki, J. IARC carcinogen update. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, A580–A581 (2005).

Yuan, T., Zhang, H., Chen, B., Zhang, H. & Tao, S. Association between lung cancer risk and inorganic arsenic concentration in drinking water: a dose-response meta-analysis. Toxicol. Res. 7, 1257–1266 (2018).

Shankar, S., Shanker, U. & Shikha Arsenic contamination of groundwater: a review of sources, prevalence, health risks, and strategies for mitigation. Sci. World J. 2014, 304524 (2014).

D’Ippoliti, D. et al. Arsenic in drinking water and mortality for cancer and chronic diseases in central Italy, 1990-2010. PLoS ONE 10, e0138182 (2015).

Ferdosi, H. et al. Arsenic in drinking water and lung cancer mortality in the United States: an analysis based on US counties and 30 years of observation (1950-1979). J. Environ. Public Health 2016, 1602929 (2016).

Ferreccio, C. et al. Arsenic, tobacco smoke, and occupation: associations of multiple agents with lung and bladder cancer. Epidemiol 24, 898–905 (2013).

Wu, M. M., Kuo, T. L., Hwang, Y. H. & Chen, C. J. Dose-response relation between arsenic concentration in well water and mortality from cancers and vascular diseases. Am. J. Epidemiol. 130, 1123–1132 (1989).

Oberoi, S., Barchowsky, A. & Wu, F. The global burden of disease for skin, lung, and bladder cancer caused by arsenic in food. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 23, 1187–1194 (2014).

UNICEF. Arsenic Primer: Guidance on the Investigation and Mitigation of Arsenic Contamination (UNICEF, 2018).

Turner, M. C. et al. Radon and lung cancer in the American Cancer Society Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 20, 438–448 (2011).

Ngoc, L. T. N., Park, D. & Lee, Y. C. Human health impacts of residential radon exposure: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 97 (2012).

Shan, X. et al. A global burden assessment of lung cancer attributed to residential radon exposure during 1990-2019. Indoor Air 32, e13120 (2022).

World Health Organization. WHO Handbook on Indoor Radon: a Public Health Perspective (WHO, 2009).

US Environmental Protection Agency. The national radon action plan – a strategy for saving lives. EPA https://www.epa.gov/radon/national-radon-action-plan-strategy-saving-lives (2023).

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. A Review of Human Carcinogens. Part F: Chemical Agents and Related Occupations (IARC, 2012).

Pira, E., Donato, F., Maida, L. & Discalzi, G. Exposure to asbestos: past, present and future. J. Thorac. Dis. 10, S237–S245 (2018).

Villeneuve, P. J., Parent, M., Harris, S. A. & Johnson, K. C. Occupational exposure to asbestos and lung cancer in men: evidence from a population-based case-control study in eight Canadian provinces. BMC Cancer 12, 595 (2012).

Lash, T. L., Crouch, E. A. & Green, L. C. A meta-analysis of the relation between cumulative exposure to asbestos and relative risk of lung cancer. Occup. Environ. Med. 54, 254–263 (1997).

Nelson, H. H. & Kelsey, K. T. The molecular epidemiology of asbestos and tobacco in lung cancer. Oncogene 21, 7284–7288 (2002).

Markowitz, S. B., Levin, S. M., Miller, A. & Morabia, A. Asbestos, asbestosis, smoking, and lung cancer. New findings from the North American Insulator cohort. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 188, 90–96 (2013).

Mossman B. T., Gualtieri A. F. in Occupational Cancers (eds.Anttila S. & Boffetta P.) 239–256 (Springer, 2020).

Thives, L. P., Ghisi, E., Thives Júnior, J. J. & Vieira, A. S. Is asbestos still a problem in the world? A current review. J. Environ. Manag. 319, 115716 (2022).

Benbrahim-Tallaa, L. et al. Carcinogenicity of diesel-engine and gasoline-engine exhausts and some nitroarenes. Lancet Oncol. 13, 663–664 (2012).

Ge, C. et al. Diesel engine exhaust exposure, smoking, and lung cancer subtype risks. a pooled exposure-response analysis of 14 case-control studies. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 202, 402–411 (2020).

Garshick, E. et al. Lung cancer and elemental carbon exposure in trucking industry workers. Env. Health Perspect. 120, 1301–1306 (2012).

Silverman, D. T. et al. The diesel exhaust in miners study: a nested case-control study of lung cancer and diesel exhaust. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 104, 855–868 (2012).

Vermeulen, R. et al. Exposure-response estimates for diesel engine exhaust and lung cancer mortality based on data from three occupational cohorts. Environ. Health Perspect. 122, 172–177 (2024).

Young, R. P. et al. COPD prevalence is increased in lung cancer, independent of age, sex and smoking history. Eur. Respir. J. 34, 380–386 (2009).

de Torres, J. P. et al. Lung cancer in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-incidence and predicting factors. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 184, 913–919 (2011).

Durham, A. L. & Adcock, I. M. The relationship between COPD and lung cancer. Lung Cancer 90, 121–127 (2015).

Young, R. P. et al. Individual and cumulative effects of GWAS susceptibility loci in lung cancer: associations after sub-phenotyping for COPD. PLoS ONE 6, e16476 (2011).

Saber Cherif, L. et al. The nicotinic receptor polymorphism rs16969968 is associated with airway remodeling and inflammatory dysregulation in COPD patients. Cells 11, 2937 (2022).

Sigel, K., Makinson, A. & Thaler, J. Lung cancer in persons with HIV. Curr. Opin. Hiv. AIDS 12, 31–38 (2017).

Shiels, M. S., Cole, S. R., Mehta, S. H. & Kirk, G. D. Lung cancer incidence and mortality among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected injection drug users. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 55, 510–515 (2010).

Sigel, K. et al. HIV as an independent risk factor for incident lung cancer. AIDS 26, 1017–1025 (2012).

Engels, E. A. et al. Elevated incidence of lung cancer among HIV-infected individuals. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 1383–1388 (2006).

Chaturvedi, A. K. et al. Elevated risk of lung cancer among people with AIDS. AIDS 21, 207–213 (2007).

Kirk, G. D. et al. HIV infection is associated with an increased risk for lung cancer, independent of smoking. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45, 103–110 (2007).

Parker, M. S., Leveno, D. M., Campbell, T. J., Worrell, J. A. & Carozza, S. E. AIDS-related bronchogenic carcinoma: fact or fiction? Chest 113, 154–161 (1998).

Patel, P. et al. Incidence of types of cancer among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population in the United States, 1992-2003. Ann. Intern. Med. 148, 728–736 (2008).

Winstone, T. A., Man, S. F., Hull, M., Montaner, J. S. & Sin, D. D. Epidemic of lung cancer in patients with HIV infection. Chest 143, 305–314 (2013).

Hessol, N. A. et al. Lung cancer incidence and survival among HIV-infected and uninfected women and men. AIDS 29, 1183–1193 (2015).

Bearz, A. et al. Lung cancer in HIV positive patients: the GICAT experience. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 18, 500–508 (2014).

O’Connor, E. A. et al. Vitamin and mineral supplements for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 327, 2334–2347 (2022).

Wei, X. et al. Diet and risk of incident lung cancer: a large prospective cohort study in UK Biobank. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 114, 2043–2051 (2021).

Xue, X. J. et al. Red and processed meat consumption and the risk of lung cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of 33 published studies. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 7, 1542–1553 (2014).

Vieira, A. R. et al. Fruits, vegetables and lung cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 27, 81–96 (2016).

Amararathna, M., Johnston, M. R. & Rupasinghe, H. P. V. Plant polyphenols as chemopreventive agents for lung cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 1352 (2016).

Alsharairi, N. A. The effects of dietary supplements on asthma and lung cancer risk in smokers and non-smokers: a review of the literature. Nutrients 11, 725 (2016).

The Lung Cancer Cohort Consortium.Circulating folate, vitamin B6, and methionine in relation to lung cancer risk in the Lung Cancer Cohort Consortium (LC3). J. Natl Cancer Inst. 110, 57–67 (2018).

Slatore, C. G., Littman, A. J., Au, D. H., Satia, J. A. & White, E. Long-term use of supplemental multivitamins, vitamin C, vitamin E, and folate does not reduce the risk of lung cancer. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 177, 524–530 (2008).

Verbeek, J. H. et al. An approach to quantifying the potential importance of residual confounding in systematic reviews of observational studies: a GRADE concept paper. Environ. Int. 157, 106868 (2021).

Cortés-Jofré, M., Rueda, J. R., Asenjo-Lobos, C., Madrid, E. & Bonfill Cosp, X. Drugs for preventing lung cancer in healthy people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3, Cd002141 (2020).

The Alpha-Tocopherol Beta Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. N. Engl. J. Med. 330, 1029–1035 (1994).

Omenn, G. S. et al. Effects of a combination of beta carotene and vitamin A on lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 1150–1155 (1996).

Pearson-Stuttard, J. et al. Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to diabetes and high body-mass index: a comparative risk assessment. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6, e6–e15 (2018).

Lennon, H., Sperrin, M., Badrick, E. & Renehan, A. G. The obesity paradox in cancer: a review. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 18, 56 (2016).

Duan, P. et al. Body mass index and risk of lung cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 5, 16938 (2015).

Ardesch, F. H. et al. The obesity paradox in lung cancer: associations with body size versus body shape. Front. Oncol. 10, 591110 (2020).

Yu, D. et al. Overall and central obesity and risk of lung cancer: a pooled analysis. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 110, 831–842 (2018).

Leiter, A. et al. Assessing the association of diabetes with lung cancer risk. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 10, 4200–4208 (2021).

Yi, Z. H. et al. Association between diabetes mellitus and lung cancer: meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 50, e13332 (2020).

Carreras-Torres, R. et al. Obesity, metabolic factors and risk of different histological types of lung cancer: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS ONE 12, e0177875 (2017).

Dziadziuszko, R., Camidge, D. R. & Hirsch, F. R. The insulin-like growth factor pathway in lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 3, 815–818 (2008).

Li, S. et al. Coexistence of EGFR with KRAS, or BRAF, or PIK3CA somatic mutations in lung cancer: a comprehensive mutation profiling from 5125 Chinese cohorts. Br. J. Cancer 110, 2812–2820 (2014).

Kris, M. G. et al. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. JAMA 311, 1998–2006 (2014).

Zhang, Y. L. et al. The prevalence of EGFR mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 7, 78985–78993 (2016).

Swanton, C. & Govindan, R. Clinical implications of genomic discoveries in lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 1864–1873 (2016).

AACR Project GENIE Consortium et al. AACR Project Genie: Powering precision medicine through an international consortium. Cancer Discov. 7, 818–831 (2017).

Dogan, S. et al. Molecular epidemiology of EGFR and KRAS mutations in 3,026 lung adenocarcinomas: higher susceptibility of women to smoking-related KRAS-mutant cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 6169–6177 (2012).

Etzel, C. J., Amos, C. I. & Spitz, M. R. Risk for smoking-related cancer among relatives of lung cancer patients. Cancer Res. 63, 8531–8535 (2003).

Matakidou, A., Eisen, T. & Houlston, R. S. Systematic review of the relationship between family history and lung cancer risk. Br. J. Cancer 93, 825–833 (2005).

Coté, M. L. et al. Increased risk of lung cancer in individuals with a family history of the disease: a pooled analysis from the International Lung Cancer Consortium. Eur. J. Cancer 48, 1957–1968 (2012).

Mucci, L. A. et al. Familial risk and heritability of cancer among twins in Nordic countries. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 315, 68–76 (2016).

Caron, O., Frebourg, T., Benusiglio, P. R., Foulon, S. & Brugières, L. Lung adenocarcinoma as part of the Li–Fraumeni syndrome spectrum: preliminary data of the LIFSCREEN randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 3, 1736–1737 (2017).

Gazdar, A. et al. Hereditary lung cancer syndrome targets never smokers with germline EGFR gene T790M mutations. J. Thorac. Oncol. 9, 456–463 (2014).

McKay, J. D. et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies new lung cancer susceptibility loci and heterogeneity in genetic susceptibility across histological subtypes. Nat. Genet. 49, 1126–1132 (2017).

Klein, R. J. & Gümüş, Z. H. Are polygenic risk scores ready for the cancer clinic? – a perspective. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 11, 910–919 (2022).

Hung, R. J. et al. Assessing lung cancer absolute risk trajectory based on a polygenic risk model. Cancer Res. 81, 1607–1615 (2021).

Dai, J. et al. Identification of risk loci and a polygenic risk score for lung cancer: a large-scale prospective cohort study in Chinese populations. Lancet Respir. Med. 7, 881–891 (2019).

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database: Incidence – SEER Research Data, 8 Registries, Nov 2021 Sub (1975-2020) – Linked To County Attributes – Time Dependent (1990–2020) Income/Rurality, 1969–2020 Counties. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer (National Cancer Institute, 2023).

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database: Mortality – All COD, Aggregated With State, Total U.S. (1969-2020), Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment. https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer (National Cancer Institute, 2022).

Paci, E. et al. Mortality, survival and incidence rates in the ITALUNG randomised lung cancer screening trial. Thorax 72, 825–831 (2017).

Infante, M. et al. Long-term follow-up results of the DANTE trial, a randomized study of lung cancer screening with spiral computed tomography. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 191, 1166–1175 (2015).

Saghir, Z. et al. CT screening for lung cancer brings forward early disease. The randomised Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial: status after five annual screening rounds with low-dose CT. Thorax 67, 296–301 (2012).

Becker, N. et al. Lung cancer mortality reduction by LDCT screening – results from the randomized German LUSI trial. Int. J. Cancer 146, 1503–1513 (2020).

de Koning, H. J. et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 503–513 (2020).

Aberle, D. R. et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 395–409 (2011).

Krist, A. H. et al. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 325, 962–970 (2021).

Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on screening for lung cancer. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 188, 425–432 (2016).

Oudkerk, M. et al. European position statement on lung cancer screening. Lancet Oncol. 18, e754–e766 (2017).

UK National Screening Committee. Adult screening programme: lung cancer. GOV.UK https://view-health-screening-recommendations.service.gov.uk/lung-cancer/ (2022).

Bach, P. B. et al. Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: a systematic review. JAMA 307, 2418–2429 (2012).

Japan Radiological Society The Japanese imaging guideline 2013. Japan Radiological Society http://www.radiology.jp/content/files/diagnostic_imaging_guidelines_2013_e.pdf (2013).

Zhou, Q. et al. China national lung cancer screening guideline with low-dose computed tomography (2018 version) [Chinese]. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi 21, 67–75 (2018).

Jang, S. H. et al. The Korean guideline for lung cancer screening. J. Korean Med. Assoc. 58, 291–301 (2015).

Triphuridet, N. & Henschke, C. Landscape on CT screening for lung cancer in Asia. Lung Cancer 10, 107–124 (2019).

Sagawa, M., Nakayama, T., Tanaka, M., Sakuma, T. & Sobue, T. A randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of thoracic CT screening for lung cancer in non-smokers and smokers of <30 pack-years aged 50–64 years (JECS study): research design. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 1219–1221 (2012).

dos Santos, R. S. et al. Do current lung cancer screening guidelines apply for populations with high prevalence of granulomatous disease? Results from the first Brazilian lung cancer screening trial (BRELT1). Ann. Thorac. Surg. 101, 481–486 (2016).

Ministéro Saúde. Protocolos clínicos e diretrizes terapêuticas em oncologia. Ministéro Saúde https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/protocolos-clinicos-e-diretrizes-terapeuticas-pcdt/arquivos/2014/livro-pcdt-oncologia-2014.pdf (2014).

Toumazis, I. et al. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of the 2021 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation for lung cancer screening. JAMA Oncol. 7, 1833–1842 (2021).

Criss, S. D., Sheehan, D. F., Palazzo, L. & Kong, C. Y. Population impact of lung cancer screening in the United States: projections from a microsimulation model. PLoS Med. 15, e1002506 (2018).

Kee, D., Wisnivesky, J. & Kale, M. S. Lung cancer screening uptake: analysis of BRFSS 2018. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 36, 2897–2899 (2021).

Cao, W. et al. Uptake of lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography in China: a multi-centre population-based study. EClinicalMedicine 52, 101594 (2022).

Quaife, S. L. et al. Lung screen uptake trial (LSUT): randomized controlled clinical trial testing targeted invitation materials. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 201, 965–975 (2020).

National Cancer Institute. Breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers – early detection summary table. NIH https://progressreport.cancer.gov/tables/breast-cervical (2022).

Jonnalagadda, S. et al. Beliefs and attitudes about lung cancer screening among smokers. Lung Cancer 77, 526–531 (2012).

Carter-Harris, L., Ceppa, D. P., Hanna, N. & Rawl, S. M. Lung cancer screening: what do long-term smokers know and believe? Health Expect. 20, 59–68 (2017).

Gesthalter, Y. B. et al. Evaluations of implementation at early-adopting lung cancer screening programs: lessons learned. Chest 152, 70–80 (2017).

Medicare. Lung cancer screenings. Medicare.gov https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/lung-cancer-screenings (2023).

Carter-Harris, L. & Gould, M. K. Multilevel barriers to the successful implementation of lung cancer screening: Why does it have to be so hard? Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 14, 1261–1265 (2017).

Modin, H. E. et al. Pack-year cigarette smoking history for determination of lung cancer screening eligibility. comparison of the electronic medical record versus a shared decision-making conversation. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 14, 1320–1325 (2017).

American Lung Association. State of lung cancer. American Lung Association https://www.lung.org/research/state-of-lung-cancer (2022).

Jia, Q., Chen, H., Chen, X. & Tang, Q. Barriers to low-dose CT lung cancer screening among middle-aged Chinese. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 17, 7107 (2020).

Novellis, P. et al. Lung cancer screening: who pays? Who receives? The European perspectives. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 10, 2395–2406 (2021).

Crosbie, P. A. et al. Implementing lung cancer screening: baseline results from a community-based ‘Lung Health Check’ pilot in deprived areas of Manchester. Thorax 74, 405–409 (2019).

Verghese, C., Redko, C. & Fink, B. Screening for lung cancer has limited effectiveness globally and distracts from much needed efforts to reduce the critical worldwide prevalence of smoking and related morbidity and mortality. J. Glob. Oncol. 4, 1–7 (2018).

Shankar, A. et al. Feasibility of lung cancer screening in developing countries: challenges, opportunities and way forward. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 8, S106–S121 (2019).

Fitzgerald, R. C., Antoniou, A. C., Fruk, L. & Rosenfeld, N. The future of early cancer detection. Nat. Med. 28, 666–677 (2022).

Liu, M. C., Oxnard, G. R., Klein, E. A., Swanton, C. & Seiden, M. V. Sensitive and specific multi-cancer detection and localization using methylation signatures in cell-free DNA. Ann. Oncol. 31, 745–759 (2020).

Hubbell, E., Clarke, C. A., Aravanis, A. M. & Berg, C. D. Modeled reductions in late-stage cancer with a multi-cancer early detection test. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 30, 460–468 (2021).

Hackshaw, A. et al. Estimating the population health impact of a multi-cancer early detection genomic blood test to complement existing screening in the US and UK. Br. J. Cancer 125, 1432–1442 (2021).

Mouritzen, M. T. et al. Nationwide survival benefit after implementation of first-line immunotherapy for patients with advanced NSCLC – real world efficacy. Cancers 13, 4846 (2021).

Smeltzer, M. P. et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer global survey on molecular testing in lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 15, 1434–1448 (2020).

Febbraro, M. et al. Barriers to access: global variability in implementing treatment advances in lung cancer. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 42, 1–7 (2022).

US Environmental Protection Agency. Learn about impacts of diesel exhaust and the Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA). EPA https://www.epa.gov/dera/learn-about-impacts-diesel-exhaust-and-diesel-emissions-reduction-act-dera (2023).

Ervik, M. et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Over Time (International Agency for Research on Cancer, accessed 1 May 2022); https://gco.iarc.fr/overtime.

Soda, M. et al. Identification of the transforming EML4–ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature 448, 561–566 (2007).

Shaw, A. T. et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 4247–4253 (2009).

Kim, H. R. et al. Distinct clinical features and outcomes in never-smokers with nonsmall cell lung cancer who harbor EGFR or KRAS mutations or ALK rearrangement. Cancer 118, 729–739 (2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made a substantial contribution to all aspects of the preparation of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

R.V. has acted as an adviser and/or consultant to AstraZeneca, Beigene, BerGenBio, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Novartis, Novocure and Regeneron, and has received research grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Onconova Therapeutics. J.P.W. has acted as an adviser and/or consultant to Atea, Banook, PPD and Sanofi and has received research grants from Arnold Consultants, Regeneron and Sanofi. A.L. declares no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology thanks D. Christiani and the other, anonymous reviewers for the peer-review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Leiter, A., Veluswamy, R.R. & Wisnivesky, J.P. The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 20, 624–639 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00798-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00798-3

This article is cited by

-

A cuproptosis score model and prognostic score model can evaluate clinical characteristics and immune microenvironment in NSCLC

Cancer Cell International (2024)

-

Exercise accelerates recruitment of CD8+ T cell to promotes anti-tumor immunity in lung cancer via epinephrine

BMC Cancer (2024)

-

Enhanced recovery after surgery program focusing on chest tube management improves surgical recovery after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery (2024)

-

Can aerosol optical depth unlock the future of air quality monitoring and lung cancer prevention?

Environmental Sciences Europe (2024)

-

Advancing accuracy in breath testing for lung cancer: strategies for improving diagnostic precision in imbalanced data

Respiratory Research (2024)