Abstract

Low detection sensitivity stemming from the weak polarization of nuclear spins is a primary limitation of magnetic resonance spectroscopy and imaging. Methods have been developed to enhance nuclear spin polarization but they typically require high magnetic fields, cryogenic temperatures or sample transfer between magnets. Here we report bulk, room-temperature hyperpolarization of 13C nuclear spins observed via high-field magnetic resonance. The technique harnesses the high optically induced spin polarization of diamond nitrogen vacancy centres at room temperature in combination with dynamic nuclear polarization. We observe bulk nuclear spin polarization of 6%, an enhancement of ∼170,000 over thermal equilibrium. The signal of the hyperpolarized spins was detected in situ with a standard nuclear magnetic resonance probe without the need for sample shuttling or precise crystal orientation. Hyperpolarization via optical pumping/dynamic nuclear polarization should function at arbitrary magnetic fields enabling orders of magnitude sensitivity enhancement for nuclear magnetic resonance of solids and liquids under ambient conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are indispensable techniques in fields reaching from chemistry and materials to biology and medicine. Despite their non-destructive nature and broad range of applications they are subject to limited sensitivity. The sensitivity is primarily limited by the weak magnetization of nuclear spins, which is dependent on the population differences between nuclear spin states. At room temperature, the fractional excess of spin state population, or polarization, can be <1 p.p.m., motivating the development of methods to enhance NMR signals by generating polarization greater than prevails in thermal equilibrium. Such methods include: optical pumping applied to noble gases1,2,3,4 and semiconductors5,6; parahydrogen-induced polarization7,8,9; low temperature dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP)10,11,12,13; chemically induced DNP14; and optical pumping with DNP of excited triplet states in organic solids15. Despite the success of each of these techniques, they are limited to either low temperatures or specific molecules. Particularly desirable would be a general method to produce hyperpolarization at similar magnetic fields and temperatures as the NMR or MRI experiment. This enhancement would enable, for example, the observation of small quantities of biomolecules under biologically relevant conditions.

Recently, it has been recognized that nuclear spin hyperpolarization generated from nitrogen vacancy (NV−) centres in diamond could provide a platform for polarization transfer to NMR/MRI samples16,17,18,19. NV− centres, with their optically polarized electron spin states and optical spin readout, have been the subject-of-interest for applications in quantum information, photonics and high-resolution sensing20, but here we are interested in their application to the polarization of nuclear spins. Nuclear spins hosted within the diamond lattice have been hyperpolarized using level anti-crossings that occur at specific crystal orientations and magnetic field strengths17,18. Evidence of nuclear spin hyperpolarization of proximate 13C spins was deduced from optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR) spectra at the level anti-crossing fields and subsequently confirmed at a value of ∼0.5% in bulk by shuttling the diamond sample to a higher magnetic field for NMR detection19. These techniques were then extended to low fields away from the anti-crossing and to arbitrarily oriented NV− centres using microwave irradiation21. Bulk 13C polarization has been generated at high field and low temperature and attributed to the coupling of the nuclear spins to the dipolar energy reservoir of the NV− ensemble16, but the precise mechanism remains unclear. Furthermore, a recent proposal has suggested the use of shallow NV− centres as a source for direct polarization transfer to a surrounding liquid22. In contrast, our method uses optical pumping of diamonds coupled with DNP under ambient conditions to obviate the need for cryogenic temperatures, sample shuttling, and precise crystal orientation and magnetic field strengths.

Here we show the generation of 13C nuclear spin polarization in diamond using microwave-driven DNP from the optically polarized electrons of NV− defects. We demonstrate bulk nuclear spin polarization of 6%, an enhancement of ∼170,000 over thermal equilibrium. This is an order of magnitude greater than previous methods using NV− centres19,21 and is achieved without precise control over magnetic field and crystal alignment. Room-temperature, hyperpolarized diamonds open the possibility of polarization transfer to arbitrary samples from an inert, non-toxic and easily separated source, a long sought-after goal of contemporary magnetic resonance.

Results

Optically pumped DNP

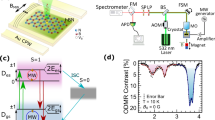

The NV− centre in diamond comprises a substitutional nitrogen atom adjacent to a vacancy. Each NV− centre has C3v symmetry with the C3 axis aligned along one of the four equivalent [111] crystal axes. The electronic ground state of the negatively charged NV− centre is a spin-1 triplet with a zero-field splitting D=2.87 GHz between the ms=±1 and ms=0 states (Fig. 1). The ms=0 state is preferentially populated via optical pumping with a 532 nm laser and spin-dependent non-radiative decay rates. Applying a magnetic field along the defect symmetry axis lifts the degeneracy of the ms=±1 states and gives rise to two distinct magnetic resonance transitions observable by ODMR. ODMR relies on a reduction in the fluorescence intensity induced by depopulation of the ms=0 state (Fig. 1a). In our experiment, 13C spins in a 4.5 mg diamond are hyperpolarized by DNP using an optically polarized microwave transition (red and blue arrows in Fig. 1b, spectra shown in Fig. 1c,d). DNP in diamond is known to occur via a combination of thermal mixing, where the dipolar energy reservoir of the interacting paramagnetic centres couples to the nuclei, and solid effect, where electron/nuclear spin flips are driven by microwave irradiation23 (See Supplementary Note 1 for a discussion of DNP mechanisms). The result of each of these mechanisms is the transfer of electron spin polarization to the nuclei. Owing to the optically polarized NV− centres used for DNP, a strong, hyperpolarized NMR signal was observed from this natural isotopic abundance sample after accumulating 60 scans with a repetition time of 60 s (Fig. 2a). These parameters were chosen to achieve sufficient signal-to-noise in a reasonable experimental time and result in a polarization slightly lower than the maximum steady-state value relevant to a single scan. For comparison and calibration, after accumulating 12,676 scans with a repetition time of 10 ms, a 10 μl sample of liquid dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), enriched to 99% 13C and doped with Gd(III), produced an NMR signal of lower amplitude than the diamond by a factor of ∼12 (Fig. 2b). From the ratio of the numbers of 13C nuclei in the diamond and DMSO samples (0.015), the number of scans needed for each and the ratio of signal amplitudes, the maximum bulk 13C polarization in the diamond is estimated to be 6%. The odd function of polarization with respect to applied microwave frequency (Fig. 2c,d) is characteristic of DNP in solids, and the opposite signs of the signals in Fig. 2c,d are consistent with population of the ms=0 state of the NV− centre. Since the width of the EPR transition is similar to the NMR frequency (∼4.5 MHz), it is expected that both solid effect and thermal mixing DNP mechanisms may be present23, and the frequency span between the maximum (occurring at 8,903 and 14,606 MHz) and minimum (8,894 and 14,615 MHz) polarizations is similar to, but not exactly, twice the NMR frequency. We attribute the dynamics to the coupled processes of DNP of nuclear spins proximate to the NV− centres, nuclear spin diffusion to the bulk material23,24 and spin-lattice relaxation. This process is shown schematically in Fig. 3a and leads to a build-up of nuclear spin polarization over several minutes (Fig. 3b).

(a) Energy levels and transitions for an NV− centre in diamond. Optical pumping with green light at 532 nm induces transitions from the ground state spin-1 triplet to the excited triplet state. Subsequent to vibrational relaxation, fluorescence is detected in the red and near-IR. Spin conserving optical transitions and spin-dependent, non-radiative intersystem crossings lead to a preferential population of the ms=0 ground state, producing electron spin hyperpolarization of the NV− centre. (b) Application of a magnetic field aligned along the NV− axis lifts the degeneracy of the ms=±1 states, giving rise to two transitions that can be driven with microwave irradiation. The two transitions, (c) between ms=0 and ms=−1, and (d) between ms=0 and ms=+1, are observed by optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR) through a reduction in the fluorescence intensity caused by a depletion of the ground ms=0 state. h=Planck's constant.

(a) 13C NMR spectra of natural abundance diamond after the accumulation of 60 scans under DNP for 60 s at 8,895 MHz (blue) and 8,907 MHz (red). (b) NMR spectrum of thermal equilibrium reference sample (99% 13C-enriched DMSO) after accumulating 12,676 scans. The diamond DNP signal corresponds to a polarization of 6%, an enhancement of ∼170,000 over thermal equilibrium. Consistent with known mechanisms of dynamic nuclear polarization, 13C nuclear polarization is an odd function of applied microwave frequency at the (c) ms=0 to ms=−1 and (d) ms=0 to ms=+1 NV− transitions. The opposite signs of these two curves are consistent with the opposite electron spin polarizations of the two NV− transitions. Data were acquired with a laser intensity of 16 W cm−2 and microwave power of 1.3 W. Error represents 95% confidence intervals for the amplitude of a Lorentzian fit to the frequency-domain data.

(a) Schematic representation of the DNP process. Direct polarization near NV− centres (red/white spheres in inset) gives rise to 13C (green spheres in inset) spin hyperpolarization. Spin diffusion carries the polarization (blue regions) from the NV− centres (red circles) to the bulk material until a steady state is reached. (b) Time dependence of 13C spin polarization obtained by 13C NMR at 4.5 MHz. Beyond ∼100 s, the spin polarization has reached a steady state that represents a balance between the hyperpolarization/spin diffusion process and the spin-lattice relaxation of the nuclear spins. (c) Hyperpolarization achieved with NV− centres misaligned 14° from the magnetic field. Error represents 95% confidence intervals for the amplitude of a Lorentzian fit to the frequency-domain data.

Orientation dependence

The OP/DNP process is expected to be effective at arbitrary orientations of the NV− defects, since the process depends on matching of the microwave frequency to a given transition, rather than a precise field strength and orientation. To test this idea, the sample was rotated 90° around the axis perpendicular to the laser and magnetic field. This ensured that no NV− centres were aligned with the magnetic field. An ODMR signal was found at 14,402 MHz, which corresponds to an NV− misalignment of 14° from the field. DNP data were collected at this frequency (Fig. 3c) showing 13C spin polarization approaching 2%. The reduction in DNP efficiency is attributed to the mixing of NV− spin states and the corresponding reduction of polarization between the NV− energy levels. However, high polarization should be present for all orientations except near the magic angle  , where the states are an equal admixture of ms=±1 and ms=0. The effectiveness of the DNP for misaligned NV− centres will be critical for the extension of this technique to randomly oriented powders, where polarization may be extracted from any crystal orientation via the integrated solid effect15. We further note that our technique should be general for a large range of magnetic fields. As long as the NV− Zeeman interaction is significantly greater than the zero-field splitting, the physics presented here should be valid, including the robustness to orientation. Near to and below the level anti-crossing, the quantization axis will no longer be solely defined by the external field and this mechanism will no longer be valid, although other polarization mechanisms may exist21.

, where the states are an equal admixture of ms=±1 and ms=0. The effectiveness of the DNP for misaligned NV− centres will be critical for the extension of this technique to randomly oriented powders, where polarization may be extracted from any crystal orientation via the integrated solid effect15. We further note that our technique should be general for a large range of magnetic fields. As long as the NV− Zeeman interaction is significantly greater than the zero-field splitting, the physics presented here should be valid, including the robustness to orientation. Near to and below the level anti-crossing, the quantization axis will no longer be solely defined by the external field and this mechanism will no longer be valid, although other polarization mechanisms may exist21.

Discussion

These results introduce a methodology for nuclear spin hyperpolarization in diamond that is robust to magnetic field strength and orientation. They demonstrate a bulk polarization of 6%, but with optimization of magnetic field, orientation and diamond samples the polarization could in theory approach the NV− spin polarization, which is of order unity20. Hyperpolarized diamonds, which can be efficiently integrated into existing fabrication techniques to create high surface area diamond devices, including nanocrystal powders, will provide a general platform for polarization transfer. We envision highly enhanced NMR of liquids and solids using existing polarization transfer techniques, such as cross-polarization in solids25 and cross-relaxation in liquids26, or direct DNP to outside nuclei from shallow NV− centres. Cross-relaxation has already been demonstrated as a method for polarization transfer between phases such as hyperpolarized 129Xe gas to solid27 and liquid28. These transfer techniques should be applicable to any sample that can be brought into intimate contact with the diamond surface, with the efficiency of polarization transfer determined by the relative rates of polarization transfer and spin-lattice relaxation. The efficiency of polarization transfer would approach 100% for long-T1 samples. Possible samples include liquids, solids and mildly frozen liquids (for example, glassy aqueous solutions) for solid-state OP/DNP with solid-state spin diffusion followed by thawing and observation of hyperpolarized liquid-state NMR. Hyperpolarization techniques based on optically polarized NV− centres could enable enhanced sensitivity of magnetic resonance experiments, resulting in decreased experimental time and lower detection limits comparable to those of contemporary techniques such as dissolution DNP and chemical-specific, parahydrogen-induced polarization. NV− centres as a polarization source could, however, be used at room temperature or under mild (near 0 °C) freeze/thaw conditions, which obviates the need for cryogenic instrumentation, shuttling between two high magnetic fields, and exogenous polarizing agents. The technique should be applicable to arbitrary target molecules, including biological systems that must be maintained at near ambient conditions.

Methods

Optically pumped DNP apparatus

To investigate DNP effects with NV− centres, we constructed a combined DNP/optically detected magnetic resonance/NMR instrument, shown schematically in Supplementary Fig. 1. The magnetic field is supplied by a custom-built electromagnet (Tel-Atomic) and is set to 420 mT. A Coherent Verdi G15 laser delivers 532 nm illumination to the sample through a Gaussian beam with a waist of 1.5 mm, essentially illuminating the entire surface of the diamond with an intensity up to 16 W cm−2. The laser intensity was chosen to maximize polarization without excessive sample heating (see Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2 for laser power dependence). Fluorescence is separated from excitation light by a dichroic mirror and detected by an avalanche photodiode. ODMR is performed by monitoring the diamond fluorescence while varying the applied microwave frequency. Microwave irradiation is delivered to the sample by a microwave loop of diameter 9.6 mm (See Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3 for microwave power dependence). NMR was performed using a Magritek Kea 2 spectrometer with a homebuilt 50-turn planar coil probe tuned to ∼4.5 MHz.

Diamond sample preparation

A commercially-available 2 mm × 2 mm × 0.32 mm, 〈100〉 surface-orientation single crystal of synthetic high-pressure, high-temperature diamond (Sumitomo) was acquired. Electron irradiation at 1 MeV with a fluence of 1018 cm−2 followed by annealing at 800 °C for 4 h in a mixture of 9% H2 and 91% He yielded an ensemble of NV− centres. NV− concentration is expected to be on the order of 1018 cm−3 under these conditions29. The crystal was mounted on a goniometer inside the electromagnet, and one of the 〈111〉 axes was aligned with the magnetic field by monitoring the ODMR spectrum. In this orientation, there are three equivalent ODMR spectra of the NV− centres along 〈111〉 axes at an angle of 109.5° with respect to the magnetic field and a single ODMR spectrum corresponding to the aligned NV− centres. With the field set to 420 mT, ODMR and DNP were performed using microwave fields at 8,900 and 14,600 MHz. For the misaligned NV− data, the sample holder/NMR probe was rotated 90° around the vertical axis, which is perpendicular to both the magnetic field and the laser. A separate reference measurement (described later) was performed for this configuration in case of unintended variations of the NMR sensitivity.

Experimental procedure

DNP data were acquired by polarizing for 60 s unless otherwise noted. Then, a  NMR pulse of duration 10 μs (calibrated via a nutation experiment) generated transverse magnetization that was inductively detected. Time-domain NMR data were apodized by exponential multiplication with a decay constant of 1 ms. After application of phase correction and a fast Fourier transform algorithm, frequency-domain spectra were fitted to single Lorentzian functions. The nuclear polarization was taken to be proportional to the amplitude of the fitted peak; error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals for the amplitude. The bulk polarization was calibrated relative to the thermal equilibrium signal of a 99% 13C-enriched sample of dimethyl sulfoxide, doped with gadolinium (III). The doping resulted in a spin-lattice relaxation time <2 ms, which allowed acquisition of ∼10,000 scans necessary for sufficient signal-to-noise ratio. See Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4 for a discussion of the validity of the calibration. The polarization build-up was monitored with a saturation-recovery pulse sequence, in which the polarization was initially destroyed with a series of

NMR pulse of duration 10 μs (calibrated via a nutation experiment) generated transverse magnetization that was inductively detected. Time-domain NMR data were apodized by exponential multiplication with a decay constant of 1 ms. After application of phase correction and a fast Fourier transform algorithm, frequency-domain spectra were fitted to single Lorentzian functions. The nuclear polarization was taken to be proportional to the amplitude of the fitted peak; error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals for the amplitude. The bulk polarization was calibrated relative to the thermal equilibrium signal of a 99% 13C-enriched sample of dimethyl sulfoxide, doped with gadolinium (III). The doping resulted in a spin-lattice relaxation time <2 ms, which allowed acquisition of ∼10,000 scans necessary for sufficient signal-to-noise ratio. See Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4 for a discussion of the validity of the calibration. The polarization build-up was monitored with a saturation-recovery pulse sequence, in which the polarization was initially destroyed with a series of  pulses followed by a variable polarization time and NMR detection. The build-up data were processed separately by exponential apodization and Fourier transform with Magritek Prospa software, followed by phase correction and fitting to Lorentzian functions to extract the amplitude.

pulses followed by a variable polarization time and NMR detection. The build-up data were processed separately by exponential apodization and Fourier transform with Magritek Prospa software, followed by phase correction and fitting to Lorentzian functions to extract the amplitude.

Additional information

How to cite this article: King, J. P. et al. Room-temperature in situ nuclear spin hyperpolarization from optically pumped nitrogen vacancy centres in diamond. Nat. Commun. 6:8965 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9965 (2015).

References

Raftery, D. Annual Reports on NMR Spectroscopy 57, Elsevier Academic Press Inc. (2006).

Walker, T. & Happer, W. Spin-exchange optical pumping of noble-gas nuclei. Rev. Mod. Phys. 69, 629–642 (1997).

Witte, C. & Schroeder, L. NMR of hyperpolarised probes. NMR Biomed. 26, 788–802 (2013).

Bouchiat, M., Carver, T. & Varnum, C. Nuclear polarization in He3 gas induced by optical pumping and dipolar exchange. Phys. Rev. Lett. 5, 373–375 (1960).

Reimer, J. A. Nuclear hyperpolarization in solids and the prospects for nuclear spintronics. Solid State NMR 37, 3–12 (2010).

Hayes, S. E., Mui, S. & Ramaswamy, K. Optically pumped nuclear magnetic resonance of semiconductors. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 052203 (2008).

Duckett, S. B. & Mewis, R. E. in Hyperpolarization Methods in NMR Spectroscopy Vol. 338, ed. Kuhn L. T. 75–103Springer-Verlag (2013).

Bowers, C. & Weitekamp, D. Transformation of symmetrization order to nuclear-spin magnetization by chemical reaction and nuclear magnetic resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 2645–2648 (1986).

Natterer, J. & Bargon, J. Parahydrogen induced polarization. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 31, 293–315 (1997).

Ni, Q. Z. et al. High frequency dynamic nuclear polarization. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1933–1941 (2013).

Griesinger, C. et al. Dynamic nuclear polarization at high magnetic fields in liquids. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 64, 4–28 (2012).

Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J. et al. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of >10,000 times in liquid-state NMR. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10158–10163 (2003).

Gajan, D. et al. Hybrid polarizing solids for pure hyperpolarized liquids through dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 14693–14697 (2014).

Goez, M. An introduction to chemically induced dynamic nuclear polarization. Concept. Magn. Reson. 7, 69–86 (2005).

Tateishi, K. et al. Room temperature hyperpolarization of nuclear spins in bulk. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7527–7530 (2014).

King, J. P., Coles, P. J. & Reimer, J. A. Optical polarization of 13C nuclei in diamond through nitrogen vacancy centers. Phys. Rev. B 81, 073201 (2010).

Fischer, R., Jarmola, A., Kehayias, P. & Budker, D. Optical polarization of nuclear ensembles in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 87, 125207 (2013).

Wang, H. et al. Sensitive magnetic control of ensemble nuclear spin hyperpolarization in diamond. Nat. Commun. 4, 1940 (2013).

Fischer, R. et al. Bulk nuclear polarization enhanced at room-temperature by optical pumping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 057601 (2013).

Doherty, M. W. et al. The nitrogen-vacancy colour centre in diamond. Phys. Rep. 528, 1–45 (2013).

Álvarez, G. A. et al. Local and bulk 13C hyperpolarization in nitrogen-vacancy-centred diamonds at variable fields and orientations. Nat. Commun 6, 8456 (2015).

Abrams, D., Trusheim, M. E., Englund, D. R., Shattuck, M. D. & Meriles, C. A. Dynamic nuclear spin polarization of liquids and gases in contact with nanostructured diamond. Nano Lett. 14, 2471–2478 (2014).

Reynhardt, E. & High, G. Dynamic nuclear polarization of diamond. I. Solid state and thermal mixing effects. J. Chem. Phys. 109, 4090–4099 (1998).

Abragam, A. Principles of Nuclear Magnetism Oxford Univ. Press (1961).

Pines, A., Gibby, M. G. & Waugh, J. Proton-enhanced NMR of dilute spins in solids. J. Chem. Phys 59, 569–590 (1973).

Slichter, C. P. Principles of Magnetic Resonance 3rd edn Springer (1996).

Gaede, H. et al. High-field cross-polarization NMR from laser-polarized xenon to surface nuclei. Appl. Magn. Reson. 8, 373–384 (1995).

Navon, G. et al. Enhancement of solution NMR and MRI with laser-polarized xenon. Science 271, 1848–1851 (1996).

Acosta, V. M. et al. Diamonds with a high density of nitrogen-vacancy centers for magnetometry applications. Phys. Rev. B 80, 115202 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, of the US Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. K.J. acknowledges fellowship support from the Republic of Korea Army. We thank Eric Scott and Melanie Drake for providing the diamond sample used in this study. We also thank Jeffrey Reimer, Birgit Hausmann and Carlos Meriles for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P.K. and A.P. conceived the project. J.P.K., C.S.S., K.J., C.C.V., R.H.P., C.E.A. and H.-J.W. designed and constructed the experimental apparatus. K.J. collected the DNP data. R.H.P and K.J. performed optical characterization of the samples. J.P.K. and A.P. wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-4, Supplementary Notes 1-3 and Supplementary References. (PDF 1707 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

King, J., Jeong, K., Vassiliou, C. et al. Room-temperature in situ nuclear spin hyperpolarization from optically pumped nitrogen vacancy centres in diamond. Nat Commun 6, 8965 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9965

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9965

This article is cited by

-

Enhancing polarization transfer from nitrogen-vacancy centers to external nuclear spins via dangling bond mediators

Communications Physics (2024)

-

Multinuclear 1D and 2D NMR with 19F-Photo-CIDNP hyperpolarization in a microfluidic chip with untuned microcoil

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Hyperpolarized water as universal sensitivity booster in biomolecular NMR

Nature Protocols (2022)

-

Hyperpolarization via dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization: new technological and methodological advances

Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine (2021)

-

Blueprint for nanoscale NMR

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.