Abstract

Organomagnesium compounds (Grignard reagents) are among the most useful organometallic reagents and have greatly accelerated the advancement of synthetic chemistry and related sciences. Nevertheless, heavy Grignard reagents based on the metals calcium, strontium or barium are not widely used, mainly due to their rather inert heavy alkaline-earth metals and extremely high reactivity of their corresponding Grignard-type reagents. Here we report the generation and reaction chemistry of butadienyl heavy Grignard reagents whose extremely high reactivity is successfully tamed. Facile synthesis of perfluoro-π-extended pentalene and naphthalene derivatives is realized by the in situ generated heavy Grignard reagents via intramolecular C–F/C–H bond cleavage. These obtained perfluorodibenzopentalene and perfluorodinaphthopentalene derivatives show low-lying LUMO levels, with one being the lowest value so far among all pentalene derivatives. Our results set an exciting example for the meaningful synthetic application of heavy Grignard reagents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For the development of organomagnesium compounds (Grignard reagents (RMgX)), Grignard was awarded with the Nobel prize in 1912. Since then, organomagnesium compounds have greatly accelerated the advancement of synthetic chemistry and related subjects1. Nevertheless, the organometallic chemistry of heavy Grignard reagents (RAeX, Ae=Ca, Sr and Ba) is still in its infancy due to the rather inert heavy alkaline-earth metals and extremely high ionicity and reactivity of Ae–C bonds2,3,4,5,6,7. The enormous reactivity of generated Ae–C bonds easily led to side reactions and obstructed the application of heavy Grignard reagents8,9,10,11,12.

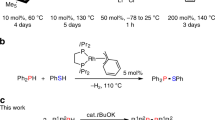

Prior efforts to develop useful reaction chemistry and synthetic applications of heavy alkaline-earth species were conducted. Unexpected results have displayed charming reactivity of Ae–X bonds (X=P, N and C). Westerhausen et al.13,14 reported the first synthetic application in which the enhanced reactivity was exhibited by the reactions between alkaline-earth metal phosphanides (Ae–P bonding) and diphenylbutadiynes. As for Mg[P(SiMe3)2]2, cis-addition to the C≡C bond of diphenylbutadiynes occurred. However, the corresponding derivatives of heavy alkaline-earth metals, calcium, strontium and barium could undergo further reactions. Barrett et al.15 set an encouraging precedent for the C–F bond activation promoted by Ca–N bonding species. The cleavage of C–F bond in a trifluoromethyl group was observed. In addition, deprotonation, oligomerization and Kumada-type cross-coupling reaction of arylcalcium halides were developed by Westerhausen and colleagues16,17,18.

The above mentioned literature reports demonstrate preliminary but exciting reaction chemistry of heavy alkaline-earth reagents bearing Ae–P or Ae–N bonds. With the aim of exploring this area, especially in the generation and synthetic applications of heavy Grignard reagents containing Ae–C bonds, design and development of new strategies are of great challenge and demand.

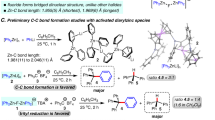

We consider that the extremely high reactivity of heavy Grignard reagents might be tamed by intramolecular nucleophilic aromatic substitution or coordination stabilization. Thus, here in this work (Fig. 1), the highly reactive heavier alkaline-earth metals are in situ prepared by the Rieke procedure, and the corresponding alkenyl Ae–C bonds are formed by the reaction between Rieke Ae and alkenyl iodides19. Subsequently, the reactions of heavy Grignard reagents containing alkenyl Ae–C bonds and the conjugated diene moiety are investigated. The successful intramolecular nucleophilic aromatic substitution is mainly due to the butadienyl organo-di-heavy Grignard reagents (double Ae–C bonds) and the formation of stable five(six)-membered rings. Intramolecular C–F and C–H bond cleavage leads to perfluoro-π-extended pentalene and naphthalene derivatives, respectively. Pentalene derivatives have attracted much recent attention because of their potential applications as organic conjugated materials. However, access to these compounds is generally very difficult. These obtained compounds exhibit the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) levels in reported pentalene derivatives, showing great potential in electron-accepting materials.

Results

Synthesis of perfluoro-π-extended pentalene derivatives

In recent years, dibenzopentalene derivatives have attracted considerable attentions because of their unique planar structures, antiaromatic characters and promising application in organic materials science20,21. Several reliable methods for the synthesis of dibenzopentalene derivatives were designed and reported22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. In case of dinaphthopentalene derivatives, Kawase et al.31 reported the unique synthesis and application in organic thin-film transistors. Introducing F atoms onto organic π-conjugated systems is an effective way to lower the energy levels, which can tune the electron transport properties32,33. Therefore, novel approaches for the synthesis of fluorodibenzopentalene and fluorodinaphthopentalene derivatives should be extremely attractive. Dibenzopentalene and dinaphthopentalene derivatives own a 6-5-5-6 fused ring system, which might be constructed by 2,3-phenyl-substituted 1,3-butadiene species. We have reported the facile synthesis of dibenzopentalene dianion from 1,4-dilithio-1,3-butadienes and Ba[N(SiMe3)2]2 (ref. 34). With this result in hand, we envisioned a novel approach from 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadienes to perfluoro-π-extended pentalenes through C–F bond cleavage35,36,37.

First, 2,3-perfluoroaryl-substituted 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadienes 1 (1a: R=n-Pr; 1b: R=n-Bu; 1c: R=n-Oct; 1d: R=(CH2)3Ph; 1e: R=Cy; 1f: R=Ph) were prepared in good isolated yields by modifying the procedures reported by Tilley and colleagues38,39, via iodination of zirconacyclopentadienes. Similarly, the 2,3-perfluoronaphthyl-substituted butadiene derivative 1g was also obtained (see the Methods). As shown in Table 1, when 1a was treated with n-BuLi, the expected perfluorodibenzopentalene derivative 2a was observed. However, the yield was rather low. Obviously, more reactive organometallic reagents were needed to cleave the C–F bonds. In 2005, Niemeyer and colleagues40 described the first heavy alkaline-earth metal C6F5 species in which short heavy alkaline-earth metal–fluorine bonds were observed. After screening various organometallic reagents including Rieke metals of alkaline earth metals, in which Rieke Mg was generated by the reaction between MgCl2 and K41, Rieke Ca/Ba were prepared by the reaction between CaI2/BaI2 and lithium biphenylide9,10, we found that Ca–C bond was the best for this C–F cleavage reaction. Other organometallic reagents gave no products or lower yields. These results demonstrated that heavy Grignard reagents exhibited excellent reactivity. The optimal reaction conditions were found to be Rieke Ca (3.0 equiv) in tetrahydrofuran (THF) at −95 °C for 3 h. Under these optimized conditions, perfluorodibenzopentalene derivative 2a was obtained in 52% isolated yield.

The scope of C–F bond activation by Ca heavy Grignard reagents was investigated under the optimized reaction conditions and the results are summarized in Fig. 2a. After formation of alkenylcalcium iodides, C–F cleavage took place twice, generating the perfluorodibenzopentalenes 2a-c in moderate isolated yields. The corresponding substituents at the 5- and 10-positions were propyl, butyl and octyl groups. The solubility of perfluorodibenzopentalenes 2a-c could be regulated by the variable carbon chains, which is very important for use as organic materials. The 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadienes 1d and 1e containing terminal phenyl and cyclohexyl groups also afforded their corresponding perfluorodibenzopentalenes 2d and 2e, respectively. When the reaction between 1,4-phenyl-substituted 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadiene 1f and Rieke Ca was carried out, the C–F cleavage process gave the perfluorodibenzopentalene 2f in 31% yield, along with a fulvene derivative (see the Supplementary Figs 1,2). In addition, the reaction of 2,3-perfluoronaphthyl-substituted butadiene derivative 1g was investigated. The perfluorodinaphthopentalene 2g was obtained in 21% isolated yield due to the relatively high reactivity of C–F bonds of perfluoronaphthyl substituents. As expected, use of the relatively mild organolithium reagent afforded 2g in 37% isolated yield. Single crystals of 2e and 2g suitable for X-ray structural analysis were obtained from hexane and chlorobenzene solutions, respectively (see Fig. 2b,c and Supplementary Figs 3 and 4). The molecular structure of 2e revealed a planar structure. A large bond alternation was observed within the pentalene core. This study on the synthesis and structural characterization of perfluoro-π-extended pentalenes 2a-g is the first example among all reports on pentalene derivatives. Meanwhile, this is the first C–F bond cleavage promoted by heavy Grignard reagents.

(a) Scope of C–F bond activation via heavy Grignard reagents. (b) Thermal ellipsoid plot of perfluorodibenzopentalene 2e with 50% thermal ellipsoids. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. (c) Thermal ellipsoid plot of perfluorodinaphthopentalene 2g with 50% thermal ellipsoids. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. The whole molecule of 2g was disordered. The major part was shown above.

Properties of perfluoro-π-extended pentalene derivatives

The photophysical and electrochemical properties of compounds 2a, 2f and 2g were investigated and the results are summarized in Table 2. As shown in Fig. 3a, these compounds exhibited two main absorption bands with vibrational fine structures. The absorption maximum of 2g showed a significant red-shift of ~50 nm compared with those of 2a and 2f, presumably due to the enlarged π-conjugated plane. The optical bandgaps of 2a, 2f and 2g were estimated from the absorption onsets (440 nm for 2a; 469 nm for 2f; 522 nm for 2g) to be 2.82, 2.65 and 2.38 eV, respectively. The above results indicate that the photophysical properties of these pentalene derivatives can be effectively modulated by structural modifications. In cyclic voltammetry experiment (Fig. 3b), reversible reductive waves were observed, revealing electron-accepting abilities of these compounds. The LUMO energy levels of compounds 2a and 2g estimated from the reductive onsets showed almost the same values, while compound 2f showed a low LUMO level of −3.56 eV, which is the lowest value among reported pentalene derivatives26,27,28,31. These features make them potential as good electron-accepting and transporting materials. All the compounds are non-emissive, which is a common phenomenon in 4n π-electron systems42.

(a) Normalized absorption spectra of 2a (purple), 2f (pink) and 2g (blue) in CHCl3 solutions (1 × 10−5 M). (b) Cyclic voltammograms of 2a (purple), 2f (pink) and 2g (blue) in o-dichlorobenzene (1 mM) with 0.1 M n-Bu4PF6 as supporting electrolyte (scan rate: 100 mV s−1). (c) Density functional theory -calculated molecular orbitals and energy levels at the B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory.

To investigate the influence of introducing F atoms onto the pentalene derivatives and their electronic properties, we performed density functional theory calculations on compounds 2a-F, 2f-F and 2g-F, together with model compounds 2a-H, 2f-H and 2g-H without F atoms on the backbone (Fig. 3c). The optimized geometries of all the compounds proved to be fully planar, in agreement with the single crystal structures. In consistence with the experimental results, the LUMO levels of compounds 2a-F and 2g-F are similar, while the HOMO level of 2g-F are 0.4 eV higher than that of 2a-F. This trend is also true in the case of 2a-H and 2g-H, meaning that extending π-conjugated plane along the long axis of pentalene derivatives mainly raised the HOMO levels, with LUMO levels almost unchanged. On the other hand, replacing the alkyl chains with phenyl rings at the 5- and 10-positions resulted in delocalized orbitals and lowered LUMO levels. Compared with the model compounds 2a-H, 2f-H and 2g-H, the perfluoro-π-extended pentalene derivatives 2a-F, 2f-F and 2g-F showed lowered HOMO and LUMO levels by ~1.0 eV. Therefore, the introduction of F atoms onto the pentalene backbones significantly lowered the orbital energy levels and the electronic properties of these perfluoro-π-extended pentalene derivatives can be finely tuned by varying the substitutents at the 5- and 10-positions.

Synthesis of naphthalene derivatives

Naphthalene derivatives are very attractive because of their applications in medicinal chemistry and material science43,44,45,46,47. Application of organometallic reagents could greatly expand the synthesis of naphthalene derivatives. Inspired by the above C–F activation and synthesis of perfluoro-π-extended pentalenes derivatives, we envisioned a similar approach might be possible to cleave aryl C–H bonds of the aryl group at the fourth position. We initiated our study with the aryl-substituted 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadienes on treatment with various organometallic reagents.

As shown in Table 3, treatment of 3a with t-BuLi or Rieke Mg afforded a trace amount of the naphthalene product 4a (ref. 41). When 3a was treated with Rieke Ca, 4a was obtained in 54% isolated yield9. Among the four different organometallic reagents, the barium reagent gave the best result with 74% isolated yield of 4a10. In this reaction, the C–H bond of the aryl group at the fourth position was cleaved.

As shown in Fig. 4, the substrate scope was examined using Ba heavy Grignard reagent (RBaI). Naphthalene derivatives 4a-f were obtained in excellent isolated yields. Both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups on the phenyl rings of 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadienes 1 were applicable.

To obtain more evidence for understanding the C–H cleavage reaction mechanism, we then attempted several experiments. First, we conducted the reaction at −40 °C. Hydrolysis of the reaction mixture afforded 4a in 20% yield, along with the mono-iodo 1,3-butadiene 5a in 39% yield, which is useful for understanding the reversion of stereochemistry at the terminal carbon bonding with a phenyl group and a Ba atom (Fig. 5a)48. We also tried the trapping experiment by the addition of I2 to the reaction mixture. As a result, product 4a protonated by ether cleavage and the iodo-substituted naphthalene derivative 4a-I was obtained49. The formation of 4a-I strongly indicates that naphthylbarium species was an intermediate in this process resulting in the desired product 4a (Fig. 5b). As shown in Fig. 5c, we next investigated the substitution effect of this reaction process using 3j with no substituent at the third position, the corresponding naphthalene product was not observed. To further research the intramolecular coordination stabilization of aromatic ring at the third position, aryl-substituted 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadienes 3k and 3l containing more steric propyl and cyclohexyl groups were tried to react with Rieke Ba. Formation of their corresponding naphthalene products were not observed. Thus, the aryl group on the third position is necessary.

Based on all the above experiments, a proposed mechanism for the formation of 4 is given in Fig. 5d. First, the intermediate A containing a Ba–C bond was formed50. Next, the reversion of stereochemistry at the terminal carbon bonding with a phenyl group and a Ba atom occurred due to the coordination of the Ba atom to the third positioned phenyl ring51,52,53. The generation of 5a at low temperature experiment also indicates the formation of intermediate B. After the generation of a second Ba–C bond, the subsequent intramolecular nucleophilic aromatic substitution would occur, generating the species D. Next, D converted to the naphthylbarium species E via C–H bond cleavage, while the BaI2 and BaH2 were removed from D. Iodination of E could afford 4a-I. Finally, hydrolysis of intermediate E gave the naphthalene product.

Discussion

We have disclosed novel reaction chemistry of heavy Grignard reagents bearing conjugated diene moiety. The high reactivity of heavy Ae–C bond was successfully tamed by intramolecular nucleophilic aromatic substitution or intramolecular coordination stabilization, obstructing side reactions to a great degree. Both of the C–F/C–H bond activation process set an exciting example for the meaningful synthetic application of heavy Grignard reagents. More importantly, a series of important perfluorodibenzopentalene and perfluorodinaphthopentalene derivatives were firstly synthesized, which showed the lowest LUMO levels among reported pentalene systems, exhibiting high potential as n-type semiconducting materials.

Methods

General methods

All reactions were carried out under a slightly positive pressure of dry and oxygen-free argon by using standard Schlenk line techniques. Unless otherwise noted, all starting materials were commercially available and were used without further purification. Solvents were purified by an Mbraun SPS-800 Solvent Purification System and dried over fresh Na chips in the glovebox. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker-400 spectrometer (FT, 400 MHz for 1H; 100 MHz for 13C) and a Bruker-500 spectrometer (FT, 500 MHz for 1H; 125 MHz for 13C) at room temperature. 19F NMR data was obtained on a Bruker-500 spectrometer with 2,2,2‐trifluoroethanol as the external standard. Chemical shifts were reported in units (p.p.m.) by assigning TMS (2,2,2‐trifluoroethanol) resonance in the 1H NMR (19F NMR) spectrum as 0.00 p.p.m. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded on a Bruker Apex IV FTMS mass spectrometer using ESI (electrospray ionization). Micro elemental analyses were performed on an Elemental Analyzer vario EL apparatus. Rieke Mg, Rieke Ca and Rieke Ba were prepared according to literature methods9,10,41. Rieke Mg was generated by the reaction between MgCl2 and K, and Rieke Ca/Ba were prepared by the reaction between CaI2/BaI2 and lithium biphenylide. The characterization data for 1, 2, 4 and 5a are described in the Supplementary Methods. The aryl-substituted 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadienes 3 are synthesized by the reported procedure38. The procedures for 1, 2, 4 and 5a are described below. All of the NMR spectra can be found in the Supplementary Figs 5–69.

Synthesis of 1a-f. A typical procedure for 1a

To a THF (60 ml) solution of Cp2ZrCl2 (2.4 mmol, 700 mg) at −78 °C was added dropwise n-BuLi (4.8 mmol, 1.6 M, 3.0 ml) with a syringe. After the addition was completed, the reaction mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 1 h. Next, 1-perfluorophenyl-2-propylacetylene (4.0 mmol, 936 mg) was added, and the reaction mixture was warmed up to 50 °C and stirred at this temperature for 3 h. The mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and CuCl (198 mg, 2.0 mmol) and I2 (1.016 g, 4.0 mmol) were added. The solution was warmed up to 25 °C and kept at this temperature for 1 h. After that, the reaction mixture was quenched with 3 N HCl and the resulting mixture was extracted with diethyl ether for three times then washed with NaHCO3(aq), Na2S2O3(aq) and brine. The extract was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to give crude product, which was subjected to SiO2 column using hexane as the eluent. 2,3-Diperfluorophenyl-1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadiene derivative 1a was synthesized in 80% yield (1,155 mg).

Synthesis of 1g

To a toluene (60 ml) solution of Cp2ZrCl2 (2.4 mmol, 700 mg) at −78 °C was added dropwise n-BuLi (4.8 mmol, 1.6 M, 3.0 ml) with a syringe. After the addition was completed, the reaction mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 1 h. Next, 1-perfluoronaphthyl-2-hexylacetylene (4.0 mmol, 1,448 mg) was added, and the reaction mixture was warmed up to 80 °C and stirred at this temperature for 6 h. The mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and CuCl (198 mg, 2.0 mmol) and ICl (648 mg, 4.0 mmol) were added. The solution was warmed up to 25 °C and kept at this temperature for 3 h. After that, the reaction mixture was quenched with 3 N HCl and the resulting mixture was extracted with diethyl ether for three times then washed with NaHCO3(aq), Na2S2O3(aq) and brine. The extract was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to give crude product, which was subjected to SiO2 column using hexane as the eluent. 2,3-Diperfluoronaphthyl-1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadiene Derivative 1g was synthesized in 51% yield (998 mg).

Synthesis of 2a-f and 2f’. A typical procedure for 2a

Rieke calcium (0.3 mmol), prepared from lithium biphenylide (0.6 mmol) and excess CaI2 (0.48 mmol, 141 mg) in THF (3 ml), was cooled to −95 °C. Then, to a THF (5 ml) solution of 2,3-diperfluorophenyl-1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadiene 1a (0.1 mmol, 72 mg) at −95 °C was added dropwise Rieke calcium solution via a syringe over 1 h. After the addition was completed, the reaction mixture was stirred at −95 °C for 2 h. After that, the reaction mixture was quenched with H2O and the resulting mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate for three times. The extract was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to give crude product, which was purified by HPLC using hexane as the eluent. Perfluorodibenzopentalene derivative 2a was synthesized in 52% yield (22 mg).

Synthesis of 2g

To an Et2O (5 ml) and hexane (5 ml) solution of 2,3-diperfluoronaphthyl-1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadiene 1g (0.1 mmol, 98 mg) at −78 °C was added dropwise n-BuLi (0.2 mmol, 1.6 M, 0.13 ml) with a syringe. After the addition was completed, the reaction mixture was allowed to room temperature and stirred for 3 h. Next, the reaction mixture was quenched with H2O and the resulting mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate for three times. The extract was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to give crude product, which was subjected to thin layer chromatography using hexane as the eluent. After that, the resulting powders need to be rinsed by chloroform. Perfluorodinaphthopentalene derivative 2g was synthesized in 37% yield (25 mg).

Synthesis of 4a-f. A typical procedure for 4a

Rieke barium (0.5 mmol), prepared from lithium biphenylide (1 mmol) and excess BaI2 (0.55 mmol, 215 mg) in THF (10 ml), was cooled to −78 °C. Next, the corresponding 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadiene derivative 3 (0.25 mmol) was added. After the addition was completed, the reaction mixture was allowed to room temperature and stirred at room temperature for 3 h. After that, the reaction mixture was quenched with H2O and the resulting mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate for three times. The extract was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to give crude product, which was subjected to SiO2 column using hexane as the eluent. Naphthalene derivative 4a was synthesized in 74% yield (48 mg).

Synthesis of 4g-h. A typical procedure for 4g

Rieke barium (0.5 mmol), prepared from lithium biphenylide (1 mmol) and excess BaI2 (0.55 mmol, 215 mg) in THF (10 ml), was warmed to 70 °C. Next, the corresponding 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadiene derivative 3 (0.25 mmol) was added. After the addition was completed, the reaction mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 h. After that, the reaction mixture was quenched with H2O and the resulting mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate for three times. The extract was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to give crude product, which was subjected to SiO2 column using hexane as the eluent. Naphthalene derivative 4g was synthesized in 62% yield (40 mg).

Synthesis of 4i

Rieke barium (0.5 mmol), prepared from lithium biphenylide (1 mmol) and excess BaI2 (0.55 mmol, 215 mg) in THF (10 ml), was cooled to −78 °C. Next, the corresponding 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadiene derivative 3 (0.25 mmol) was added. After the addition was completed, the reaction mixture was allowed to −20 °C and stirred at −20 °C for 3 h. After that, the reaction mixture was quenched with H2O and the resulting mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate for three times. The extract was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to give crude product, which was subjected to SiO2 column using hexane as the eluent. Naphthalene derivative 4i was synthesized in 42% yield (31 mg).

Synthesis of 5a

Rieke barium (0.5 mmol), prepared from lithium biphenylide (1 mmol) and excess BaI2 (0.55 mmol, 215 mg) in THF (10 ml), was cooled to −78 °C. Next, the corresponding 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadiene derivative 3 (0.25 mmol) was added. After the addition was completed, the reaction mixture was allowed to −40 °C and stirred at −40 °C for 1 h. After that, the reaction mixture was quenched with H2O and the resulting mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate for three times. The extract was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to give crude product, which was subjected to SiO2 column using hexane as the eluent. 1-Iodo-1,3-butadiene derivative 5a was synthesized in 39% yield (39 mg).

Synthesis of 4a and 4a-I

Rieke barium (0.5 mmol), prepared from lithium biphenylide (1 mmol) and excess BaI2 (0.55 mmol, 215 mg) in THF (10 ml), was cooled to −78 °C. Then, the corresponding 1,4-diiodo-1,3-butadiene derivative 3 (0.25 mmol) was added. After the addition was completed, the reaction mixture was allowed to room temperature and stirred at room temperature for 1 h. After that, to the reaction mixture was added I2 (0.5 mmol, 127 mg) and the resulting mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate for three times. The extract was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to give crude product, which was subjected to SiO2 column using hexane as the eluent. 4a and 4a-I was synthesized in 68% yield (53 mg).

X-ray crystallographic analysis

Single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown from hexane (2f′, 2e and1a) or chlorobenzene (2g) solution. Data collections were performed at 100 K for 2f′, 2e and 1a on a SuperNova diffractometer, using graphite-monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ=0.71073 Å). Data of 2g was performed at 100 K on a SuperNova diffractometer, using graphite-monochromated Cu Kα radiation (λ=1.54184 Å). Using Olex2 (ref. 54), these structures were solved with the ShelXS and refined with the ShelXL55 refinement package using Least Squares minimization. Refinement was performed on F2 anisotropically for all the non-hydrogen atoms by the full-matrix least-squares method. The hydrogen atoms were placed at the calculated positions and were included in the structure calculation without further refinement of the parameters. In the case of 2g, the whole molecule was disordered and treated with 61 and 39% occupancy. The disordered part1 and part2 are related by local two-fold axis, which is equivalent to a local mirror plane perpendicular to the plane of the figure. Crystallographic data have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre as supplementary publication numbers. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The thermal ellipsoid plot in the Fig. 2b,c and Supplementary Figs 2–4 and 70 were drawn by Ortep-3 v1.08 (ref. 56). See Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Data 1–4 for the crystal data details of 2f′, 2e, 2g and 1a.

Photophysical and electrochemical details

Absorption spectra was recorded on PerkinElmer Lambda 750 ultraviolet–visible spectrometer in CHCl3 solutions (1 × 10−5 M). Cyclic voltammetry was performed on BASi Epsilon workstation and measurements were carried out in dichlorobenzene (1 mM) containing 0.1 M n-Bu4NPF6 as supporting electrolyte (scan rate: 100 mV s–1). Glassy carbon electrode was used as a working electrode, a platinum sheet as a counter electrode and Ag/AgCl as a reference electrode.

Computational details

Density functional theory calculations were performed at the B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) level using the Gaussian 09 software package57. See Supplementary Table 2 for the Cartesian coordinates.

Additional information

Accession codes: The X-ray crystal structure information is available at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers CCDC-993609 (2f’), CCDC-1001290 (2e), CCDC-953857 (2g) and CCDC-953855 (1a). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

How to cite this article: Li, H. et al. Intramolecular C–F and C–H bond cleavage promoted by butadienyl heavy grignard reagents. Nat. Commun. 5:4508 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5508 (2014).

References

Seyferth, D. The Grignard reagents. Organometallics 28, 1598–1605 (2009).

Hanusa, T. P. Non-cyclopentadienyl organometallic compounds of calcium, strontium and barium. Coord. Chem. Rev. 210, 329–367 (2000).

Alexander, J. S. & Ruhlandt-Senge, K. Not Just heavy ‘‘Grignards’’: recent advances in the organometallic chemistry of the alkaline earth metals calcium, strontium and barium. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 2761–2774 (2002).

Westerhausen, M., Gärtner, M., Fischer, R. & Langer, J. Aryl calcium compounds: syntheses, structures, physical properties, and chemical behavior. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 1950–1956 (2007).

Westerhausen, M. Heavy Grignard reagents–synthesis and reactivity of organocalcium compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 252, 1516–1531 (2008).

Smith, J. D. Organometallic compounds of the heavier s-block elements–What next? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 6597–6599 (2009).

Harder, S. Geminal dianions stabilized by phosphonium substituents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 255, 1252–1267 (2011).

Alexander, J. S. & Ruhlandt-Senge, K. Barium triphenylmethanide: an examination of anion basicity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40, 2658–2660 (2001).

Wu, T.-C., Xiong, H. & Rieke, R. D. Organocalcium chemistry: preparation and reactions of highly reactive calcium. J. Org. Chem. 55, 5045–5051 (1990).

Yanagisawa, A., Habaue, S., Yasue, K. & Yamamoto, H. Allylbarium reagents: unprecedented regio- and stereoselective allylation reactions of carbonyl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 6130–6141 (1994).

Yanagisawa, A., Takahashi, H. & Arai, T. Reactive barium-promoted reformatsky-type reaction of α-chloroketones with aldehydes. Chem. Commun. 580–581 (2004).

Yanagisawa, A., Suzuki, T., Koide, T., Okitsu, S. & Arai, T. Selective propargylation of carbonyl compounds and imines with barium reagents. Chem. Asian J. 3, 1793–1800 (2008).

Westerhausen, M., Digeser, M. H., Nöth, H., Seifert, T. & Pfitzner, A. A unique barium-carbon bond: mechanism of formation and crystallographic characterization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 6722–6725 (1998).

Westerhausen, M. et al. 2,5-diphenyl-3,4-bis(trimethylsilyl)-1-phosphacyclopentadienide as a ligand at calcium, strontium and tin(II). Inorg. Chem. 38, 3207–3214 (1999).

Barrett, A. G. M., Crimmin, M. R., Hill, M. S., Hitchcock, P. B. & Procopiou, P. A. Trifluoromethyl coordination and C-F bond activation at calcium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 6339–6342 (2007).

Gärtner, M., Görls, H. & Westerhausen, M. Heteroleptic phenylcalcium derivatives via metathesis reactions of PhCa(thf)4I with potassium compounds. Organometallics 26, 1077–1083 (2007).

Fischer, R. et al. THF solvates of extremely soluble bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)calcium and tris(2,6-dimethoxyphenyl)-dicalcium iodide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 1618–1623 (2007).

Langer, J., Köhler, M., Görls, H. & Westerhausen, M. Arylcalcium halides as substrates in Kumada-type cross-coupling reactions. J. Organomet. Chem. 751, 563–567 (2014).

Rieke, R. D. Preparation of organometallic compounds from highly reactive metal powders. Science 246, 1260–1264 (1989).

Saito, M. Synthesis and reaction of dibenzo[a,e]pentalene. Symmetry 2, 950–969 (2010).

Hopf, H. Pentalenes–From highly reactive antiaromatics to substrates for material science. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 12224–12226 (2013).

Saito, M., Nakamura, M., Tajima, T. & Yoshioka, M. Reduction of phenyl silyl acetylenes with lithium: unexpected formation of a dilithium dibenzopentalenide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 1504–1507 (2007).

Levi, Z. U. & Tilley, T. D. Versatile synthesis of pentalene derivatives via the Pd-catalyzed homocoupling of haloenynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 2796–2797 (2009).

Xu, F., Peng, L., Orita, A. & Otera, J. Dihalo-substituted dibenzopentalenes: their practical synthesis and transformation to dibenzopentalene derivatives. Org. Lett. 14, 3970–3973 (2012).

Hashmi, A. S. K. et al. Gold-catalyzed synthesis of dibenzopentalenes–Evidence for gold vinylidenes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 354, 555–562 (2012).

Maekawa, T., Segawa, Y. & Itami, K. C-H activation route to dibenzo[a,e]pentalenes: annulation of arylacetylenes promoted by PdCl2-AgOTf-o-chloranil. Chem. Sci. 4, 2369–2373 (2013).

Chen, C. et al. Dibenzopentalenes from B(C6F5)3-induced cyclization reactions of 1,2-bis(phenylethynyl)benzenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 5992–5996 (2013).

Zhao, J., Oniwa, K., Asao, N., Yamamoto, Y. & Jin, T. Pd-catalyzed cascade crossover annulation of o-alkynylarylhalides and diarylacetylenes leading to dibenzo[a,e]pentalenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10222–10225 (2013).

Zhu, C. et al. Stabilization of anti-aromatic and strained five-membered rings with a transition metal. Nat. Chem. 5, 698–703 (2013).

London, G. et al. Pentalenes with novel topologies: exploiting the cascade carbopalladation reaction between alkynes and gem-dibromoolefins. Chem. Sci. 5, 965–972 (2014).

Kawase, T. et al. Dinaphthopentalenes: pentalene derivatives for organic thin-film transistors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 7728–7732 (2010).

Facchetti, A. et al. Building blocks for n-type organic electronics: regiochemically modulated inversion of majority carrier sign in perfluoroarene-modified polythiophene semiconductors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 3900–3903 (2003).

Sakamoto, Y. et al. Perfluoropentacene: high-performance p-n junctions and complementary circuits with pentacene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 8138–8140 (2004).

Li, H., Wei, B., Xu, L., Zhang, W.-X. & Xi, Z. Barium dibenzopentalenide as a main-group metal η8 complex: facile synthesis from 1,4-dilithio-1,3-butadienes and Ba[N(SiMe3)2]2, structural characterization, and reaction chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 10822–10825 (2013).

Amii, H. & Uneyama, K. C-F bond activation in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 109, 2119–2183 (2009).

Clot, E. et al. C-F and C-H bond activation of fluorobenzenes and fluoropyridines at transition metal centers: how fluorine tips the scales. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 333–348 (2011).

Stahl, T., Klare, H. F. T. & Oestreich, M. Main-group Lewis acids for C-F bond activaton. ACS Catal. 3, 1578–1587 (2013).

Xi, C., Huo, S., Afifi, T. H., Hara, R. & Takahashi, T. Remarkable effect of copper chloride on diiodination of zirconacyclopentadienes. Tetrahedron Lett. 38, 4099–4102 (1997).

Johnson, S. A. et al. Regioselective coupling of pentafluorophenyl substituted alkynes: mechanistic insight into the zirconocene coupling of alkynes and a facile route to conjugated polymers bearing electron-withdrawing pentafluorophenyl substituents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 4199–4211 (2003).

Hauber, S.-O., Lissner, F., Deacon, G. B. & Niemeyer, M. Stabilization of aryl-calcium, -strontium, and -barium compounds by designed steric and π-bonding encapsulation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 5871–5875 (2005).

Rieke, R. D. & Bales, S. E. Activated Metals. IV. Preparation and reactions of highly reactive magnesium metal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 96, 1775–1781 (1974).

Chase, D. T. et al. Electron-accepting 6,12-diethynylindeno[1,2-b]fluorenes: synthesis, crystal structures, and photophysical properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 11103–11106 (2011).

Viswanathan, G. S., Wang, M. & Li, C.-J. A highly regioselective synthesis of polysubstituted naphthalene derivatives through gallium trichloride catalyzed alkyne-aldehyde coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 2138–2141 (2002).

Kabalka, G. W., Ju, Y. & Wu, Z. A new titanium tetrachloride mediated annulation of α-aryl-substituted carbonyl compounds with alkynes: a simple and highly efficient method for the regioselective synthesis of polysubstituted naphthalene derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 68, 7915–7917 (2003).

Yoshikawa, E. & Yamamoto, Y. Palladium-catalyzed intermolecular controlled insertion of benzyne-benzyne-alkene and benzyne-alkyne-alkene–Synthesis of phenanthrene and naphthalene derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 173–175 (2000).

Zhou, H., Xing, Y., Yao, J. & Chen, J. Sulfur-assisted propargyl-allenyl isomerizations and electrocyclizations for the convenient and efficient synthesis of polyfunctionalized benzenes and naphthalenes. Org. Lett. 12, 3674–3677 (2010).

Feng, C. & Loh, T.-P. Palladium-catalyzed bisolefination of C-C triple bonds: a facile method for the synthesis of naphthalene derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 17710–17712 (2010).

Knorr, R., Lattke, E. & Räpple, E. Der konformative ortho-effekt bei o-tolylstilbenen und deren vinyllithiumderivaten. Chem. Ber. 114, 1581–1591 (1981).

Fischer, R., Gärtner, M., Görls, H. & Westerhausen, M. Synthesis of 2,4,6-trimethylphenylcalcium iodide and degradation in THF solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 609–612 (2006).

Köhler, M., Görls, H., Langer, J. & Westerhausen, M. 1-Alkenylcalcium iodide: synthesis and stability. Eur. Chem. J. 20, 5237–5239 (2014).

Harder, S. & Lutz, M. The phosphonium dibenzylide anion as a ligand in organobarium chemistry. Organometallics 16, 225–230 (1997).

Westerhausen, M. et al. Synthesis of strontium and barium bis{tris[(trimethylsilyl)methyl]zincates} via the transmetalation of bis[(trimethylsilyl)methyl]zinc. Organometallics 20, 893–899 (2001).

Loh, C., Seupel, S., Görls, H., Krieck, S. & Westerhausen, M. Structural evidence of strong calcium-π interactions to aryl substituents stabilized by coexistent agostic bonds to alkyl groups. Organometallics 33, 1480–1491 (2014).

Dolomanov, O. V., Bourhis, L. J., Gildea, R. J., Howard, J. A. K. & Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 42, 339–341 (2009).

Sheldrick, G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. A64, 112–122 (2008).

Farrugia, L. J. ORTEP-3 for Windows - a version of ORTEP-III with a Graphical User Interface (GUI). J. Appl. Cryst. 30, 565–566 (1997).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09 Revision B.01 (Gaussian, Inc. (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major State Basic Research Development Program (2012CB821600) and Natural Science Foundation of China. We also thank Professor Xiang Hao of ICCAS for useful discussions and comments on the the refinement of X-ray data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.X. conceived and supervised the project. H.L. and B.W. planned and carried out the experiment work. H.L. recorded all NMR data. L.X. and W.-X.Z. solved all X-ray structures. X.-Y.W. conducted the photophysical and electrochemical study of perfluorodibenzopentalene and perfluorodinaphthopentalene derivatives. X.-Y.W. conceived the theoretical work and conducted theoretical computations. Z.X., J.P. and W.-X.Z. drafted the paper. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the preparation of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Tables, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Data

Supplementary Figures 1-70, Supplementary Tables 1-2 and Supplementary Methods (PDF 3385 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

The crystallographic data of 2f'. (TXT 368 kb)

Supplementary Data 2

The crystallographic data of 2e. (TXT 131 kb)

Supplementary Data 3

The crystallographic data of 2g. (TXT 181 kb)

Supplementary Data 4

The crystallographic data of 1a. (TXT 528 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Wang, XY., Wei, B. et al. Intramolecular C–F and C–H bond cleavage promoted by butadienyl heavy Grignard reagents. Nat Commun 5, 4508 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5508

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5508

This article is cited by

-

Opportunities with calcium Grignard reagents and other heavy alkaline-earth organometallics

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2023)

-

Rhodium-catalysed C(sp2)–C(sp2) bond formation via C–H/C–F activation

Nature Communications (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.