Abstract

To date, slow Set operation speed and high Reset operation power remain to be important limitations for substituting dynamic random access memory by phase change memory. Here, we demonstrate phase change memory cell based on Ti0.4Sb2Te3 alloy, showing one order of magnitude faster Set operation speed and as low as one-fifth Reset operation power, compared with Ge2Sb2Te5-based phase change memory cell at the same size. The enhancements may be rooted in the common presence of titanium-centred octahedral motifs in both amorphous and crystalline Ti0.4Sb2Te3 phases. The essentially unchanged local structures around the titanium atoms may be responsible for the significantly improved performance, as these structures could act as nucleation centres to facilitate a swift, low-energy order-disorder transition for the rest of the Sb-centred octahedrons. Our study may provide an alternative to the development of high-speed, low-power dynamic random access memory-like phase change memory technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phase change memory (PCM) is one of the promising candidates for ‘universal memory’, based on the rapidly reversible phase transition between amorphous (a-) and crystalline (c-) states of chalcogenide alloys and accompanied large electrical contrast1,2. To melt a PCM material and quench it into the a-state (Reset operation), an electrical pulse of large magnitude and short duration is required. In contrast, to realize the c-state (Set operation), a smaller magnitude and longer duration pulse is needed to heat the material to a temperature between crystallization temperature (Tc) and melting point (Tm). Because of its low cost, high reliability and compatibility with the complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technology, Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST)-based PCM has already been applied to mobile electronics, replacing NOR flash memory (Micron announces availability of PCM for mobile devices- http://investors.micron.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=692563, 2012). However, the slow Set speed and high Reset power remain to be important limitations for substituting DRAM by PCM, as the DRAM requires rigorously <10 ns access time and 10−11~10−12 J program energy3.

Many efforts have been made to increase the operation speed and/or decrease the power requirement to operate the PCM. These include the following: (I) confined small cell: confined dash-type cell (7.5 nm in width) of Sb-rich GST can reach 30 ns Set speed with >1011 cycles3,4. (II) Initialization electrical pulse: a weak incubation voltage pulse (~0.3 V at 10 ns) on GST can help to pre-form fourfold membered atomic rings, which are the precursors for distorted octahedrons in rocksalt c-GST5,6. (III) Diminishing grain size: as the grain size of the GST is reduced from 17 to 13 nm, the Set time can be reduced from 44 to 40 ns7,8. In contrast, reducing the Reset power can not only prolong PCM cell life to compete with DRAM (>1015 cycles)3, but can also effectively lower the standards for drive capability of gating device to achieve high-density integration9,10. However, because of the high Tm (600–630 °C)11 for the GeTe-Sb2Te3 pseudobinary alloys, merely regulating the composition seems not to be very effective. All the methods above inadvertently increase the design and fabrication difficulties of the DRAM-like PCM. This prompts us to explore alternative and simpler approaches to increase the working speed while reducing the working power.

In the present work, the concept of introducing robust pinning sites into Sb2Te3 (ST) via Ti doping, which forms metal-centred or Ti-centred atomic motifs (TCAMs), is proposed. The TCAM describes a local atomic configuration where the Ti atom occupies the central site of a distorted or defective octahedron and the Te(Sb) atoms occupy the vertex sites. With this approach, at least one order of magnitude faster Set speed and as low as one-fifth of the Reset energy were achieved on Ti-doped ST cell compared with those of GST cell with the same size.

The rationale to suggest TCAM is as follows: in GST, the widely accepted phase change models concern with nucleation mechanisms that are facilitated through either a cavity-supported reorientation of four-membered ring structures12,13,14 or a reconfiguration of tetrahedrally bonded Ge atoms to octahedrally bonded Ge atoms15,16. Both models involve considerable atomic rearrangements. To make the process easier, it may be beneficial to pin the local bonding environment of cation M in an octahedral configuration in M-Sb-Te alloy. This way, local rearrangements of the atoms, as well as the Sb-centred motifs adjacent to the M-centred motifs, can be made in favour of the octahedral alignment for long-range order. It means TCAMs should commonly exist in both a- and c- phases. Less configuration changes make it possible for the M-centred local structures act as intrinsic nucleation centres to lower the energy barriers required for phase transition. The TCAM represents a phase transition mechanism qualitatively different from that of GST.

Results

Comparison of Set operation speed

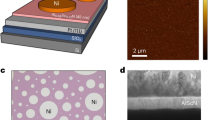

The cross-section structure of a T-shaped PCM cell with a diameter (D) of 190 nm bottom electrode contact (BEC) is presented in Fig. 1a, which is fabricated by the 0.13 μm CMOS technology. As the magnitude of applied voltage pulse reaches 1.3 V, the Ti0.4Sb2Te3 (TST) cell shows a Set speed of ~6 ns, while the GST cell with the same size requires ~75 ns even at 1.6 V (see Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1). Namely one order of magnitude faster Set speed can be achieved. The TST cell is reasonably stable, too, as after ~107 cycles (see Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 2), Ti, Sb and Te are still uniformly distributed without any sign of severe segregation.

(a) Cross-sectional TEM image of a T-shaped phase-change memory cell. The scale bar corresponds to 200 nm. The diameter (D) of the W bottom electrode contact (BEC) is ~190 nm. The thicknesses for the Al top electrode, TiN layer and Ti0.4Sb2Te3 (TST) film are ~300, ~15 and ~170 nm, respectively. Insets show element mapping for Ti, Sb and Te after ~107 Set-Reset cycles. (b) Set operation speeds for the TST- and Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST)-based PCM cells with the same D=190 nm W BEC.

Comparison of Reset operation power

Figure 2 shows that even the Reset energy of the TST cell with D=190 nm BEC (3.12 × 10−9 J) can be noticeably less than that of the GST cell with much smaller D=80 nm BEC (4.20 × 10−9 J), and a substantial reduction (~78%) of Reset energy is achieved on TST cell with the same D=80 nm BEC (0.95 × 10−9 J) as GST cell. Inset in Fig. 2 also shows an 82% reduction of Reset current obtained on the TST cell, compared with the GST cell with the same D=80 nm BEC.

Reset energy (E) as a function of bottom electrode contact (BEC) diameter (D) for the Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST) and Ti0.4Sb2Te3 (TST) cells. Inset shows resistance versus Reset current (IRst) curves with a fixed pulse width of 1,000 ns (t). Transient Reset voltage (URst) across the cell is recorded once the Reset state is reached. The input Reset energy can thus be calculated as E=IRst·URst·t. The Reset energies are (0.95, 3.12, 4.20, 9.28) × 10−9 J for TST (D=80 nm), TST (D=190 nm), GST (D=80 nm) and GST (D=130 nm) cells, respectively.

Such swift and low-energy switching features, at the same time, do not affect the stability of both the Set and Reset data states of the TST cell. In fact, the data retention (Supplementary Fig. 3) and resistance drift (Supplementary Fig. 4) properties of the TST cell are comparable to those of the GST cell. We thus expect that once the fabrication and programming methods are optimized, the overall device performance will be improved further, ensuring future DRAM-like device applications.

Homogeneous phase and lower melting point of TST

In-situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) is used to characterize 200-nm thick ST and TST films on Si substrate, as shown in Fig. 3a,b. For ST, the as-deposited film is partially crystallized because of its low Tc. The FCC (face-centred cubic) to HEX (hexagonal) transition takes place at 220 °C (ref. 17). For TST, the as-deposited film is amorphous. At above 160 °C, it starts to crystallize. While the diffraction peaks are similar to HEX-ST, they are broader, implying an obvious inhibition of grain growth due to Ti doping. No peaks belonging to the Te, Ti-Sb, or Ti-Te phases were observed, which also indicates that the c-TST is a homogeneous phase. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) study (Fig. 3c) reveals the melting process of TST commencing at 542.8 °C (=Tm). Note that Tm for TST is about 75 °C lower than that for GST (616 °C)11. Therefore, less Reset energy is required for the TST cell of similar dimensions.

In situ X-ray diffraction curves of (a) Sb2Te3 (ST) and (b) Ti0.4Sb2Te3 (TST) films at different temperatures. (c) Differential scanning calorimetry curve of TST material. The heating rate is 10 °C min−1. The curve shows an exothermic peak of crystallization as well as an endothermic peak of melting.

Discussion

Usually, uniformity is an important factor for PCM cyclability; indeed, the lattice parameters (a) of GeTe and Sb2Te3 constructing the flagship (GeTe)n(Sb2Te3)m alloys only deviate slightly (~2.2% for HEX lattice and ~1.0% for rocksalt lattice)18. In contrast, Si-Te, Al-Te and Cu-Te alloys all have noticeably larger lattice mismatch with Sb2Te3. Not surprisingly, their incorporation into Sb2Te3 causes severe phase separation19,20,21. TiTe2 has the same HEX lattice as Sb2Te3, but a ~11% lattice parameter (a) mismatch with Sb2Te3 (ref. 22). Still it is capable of forming superlattice with Sb2Te3 (ref. 23). To understand this unique and unexpected behaviour of TST, we performed first-principles calculations (see Methods for details).

The ST belongs to the  space group and is composed of HEX close-packed quintuple atomic layers along the c-axis (Fig. 4a)24. Rather than modelling the exact experimental composition, we calculate the formation energy of a single Ti atom at various ST lattice sites in a 135-atom supercell to examine the effects of introducing Ti. The most stable site for the Ti is to replace Sb (TiSb) with six Te nearest neighbours (Supplementary Fig. 5). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analyses (Supplementary Fig. 5) confirm this Ti-Te bonding. To identify the bonding chemistry between Ti and Te, Fig. 4 shows the charge density difference (CDD)25: in the Sb-centred atomic motif (Fig. 4b), there are three strong and three weak bonds26. In contrast, in the TCAM (Fig. 4c), all the six bonds between Ti and Te are strong (covalent) bonds with noticeable charge accumulation at the bond centre similar to TiTe2 (ref. 27). Ti has the d2s2 electronic configuration; the strong covalent interaction is originated from the overlapping between Ti-3d and Te-5p orbitals27. This covalent bonding may account for the rigidity of the TCAMs during phase transition. To compensate for the local rigidity, Te-Sb bonds in the adjacent layer without the Ti are significantly elongated and weakened, as indicated in Fig. 4a by dashed lines. These weakened bonds may be deformed to accommodate the 11% lattice mismatch with ST. They may also be ruptured to break the long-range order during amorphization, leading to a low-energy Reset operation as shown in Fig. 2.

space group and is composed of HEX close-packed quintuple atomic layers along the c-axis (Fig. 4a)24. Rather than modelling the exact experimental composition, we calculate the formation energy of a single Ti atom at various ST lattice sites in a 135-atom supercell to examine the effects of introducing Ti. The most stable site for the Ti is to replace Sb (TiSb) with six Te nearest neighbours (Supplementary Fig. 5). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analyses (Supplementary Fig. 5) confirm this Ti-Te bonding. To identify the bonding chemistry between Ti and Te, Fig. 4 shows the charge density difference (CDD)25: in the Sb-centred atomic motif (Fig. 4b), there are three strong and three weak bonds26. In contrast, in the TCAM (Fig. 4c), all the six bonds between Ti and Te are strong (covalent) bonds with noticeable charge accumulation at the bond centre similar to TiTe2 (ref. 27). Ti has the d2s2 electronic configuration; the strong covalent interaction is originated from the overlapping between Ti-3d and Te-5p orbitals27. This covalent bonding may account for the rigidity of the TCAMs during phase transition. To compensate for the local rigidity, Te-Sb bonds in the adjacent layer without the Ti are significantly elongated and weakened, as indicated in Fig. 4a by dashed lines. These weakened bonds may be deformed to accommodate the 11% lattice mismatch with ST. They may also be ruptured to break the long-range order during amorphization, leading to a low-energy Reset operation as shown in Fig. 2.

(a) Hexagonal lattice of Ti0.4Sb2Te3 with charge density difference. The differences are calculated with respect to that of a superposition of isolated atoms. The isosurface (transparent yellow area) shows electron pileup mostly at the bonds. The isosurface value is fixed at +0.005 e a0−3 (a0=bohr). (b) The Sb-centred atomic motif has three strong bonds and three weak bonds. (c) The Ti-centred atomic motif has six strong bonds and no weak bond. The formation of six strong Ti-Te bonds weakens some of the adjacent Te-Sb bonds (dashed line in (a)).

Figure 5a shows the calculated atomic structure of a-TST by using the melt-quench molecular dynamics technique. Figure 5b,c compare the coordination number (CN) and bond angle distribution (BAD) between a-TST and a-GST. Note that CNs for Ge in a-GST are 3, 4 and 5, whereas those for Ti in a-TST are mainly 6 and 7, respectively. These can be contrasted to the ideal CN for rocksalt=6. We also notice that, with respect to the ideal 90° rocksalt bond angle, the peak position of the bond angles for Ti decreases by 5° to 85°, while that for Ge increases by 5° to 95°. It has been established that a-GST has both tetrahedral Ge of sp3 bonding (109.5°) and octahedral Ge of p3 bonding (90°)16,28,29. The 95° Ge peak in Fig. 5c is consistent with the coexistence of sp3 and p3 bonding. In comparison, the BAD peaks for Sb and Te in both a-GST and a-TST remain to be around 90° (see inset in Fig. 5c). In contrast, the higher CN and less-than-90° BAD of Ti suggest that the TCAMs in a-TST remain to be octahedrons with perhaps some distortions. Specifically, 42% of the Ti are in the form of Ti-Te6 or Sb-Ti-Te5 and another 41% are sevenfold coordinated. We speculate that the sevenfold motifs may be easier to transform to sixfold TCAMs on phase transition than the Ge motifs with CN≤5. Thus, fewer bond breaking may be required, accompanied by considerably less structural changes, for the TCAMs in Fig. 5d to form nucleation centres for the subsequent growth of the c-phase. In this regard, we note that the structure ordering of growth-dominated AgInSbTe may take place by aligning Sb-centred octahetrons near the amorphous to crystalline boundary30. The Sb-centred octahetrons in a-TST, around TCAMs as the nucleation centres, may also be easily aligned to realize long-range order.

(a) The amorphous structure of Ti0.4Sb2Te3 (TST), showing a majority of the Ti, are bonded with Te and sixfold coordinated in an octahedral-like geometry. (b) The coordination number distribution of Ge and Ti in the respective amorphous model. (c) The bond angle distributions (BADs) around Ge in amorphous Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST) and Ti in amorphous TST. Inset shows the BADs around Sb and Te in amorphous GST and TST, respectively. Vertical dash lines indicate the positions of 60, 90 and 109.5°. (d) Proposed Ti-centred atomic motifs (TCAMs) in amorphous and crystalline TST.

One may also compare the crystallization speed in terms of the ABAB-type four-membered rings, where A=(Ge and Sb) or (Ti and Sb) and B=Te. These distorted four-membered rings, proposed by Akola et al.12 and Hegedüs et al.14 to resemble the chemically ordered structural blocks of the rocksalt phase, may serve as the nucleation sites, whose rapid growth and accompanied reorientation aided by a large concentration of cavities may explain the observed rapid crystallization of the ordered phase. Figure 6a shows that, among all the four-membered rings, a-TST has a larger number of ABAB rings than those of a-GST. Furthermore, inset in Fig. 6a shows that, per Ti (Ge) atom, the number of  rings is twice more than that of

rings is twice more than that of  rings. This means Ti is obviously more likely to form four-membered rings than Ge does. All these analyses consistently suggest that Ti doping increases the probability and the number of the nucleation centres. Hence, crystallization of the TST should be a nucleation-dominated process, which is also the case for GST (Fig. 6b (first row)).

rings. This means Ti is obviously more likely to form four-membered rings than Ge does. All these analyses consistently suggest that Ti doping increases the probability and the number of the nucleation centres. Hence, crystallization of the TST should be a nucleation-dominated process, which is also the case for GST (Fig. 6b (first row)).

(a) The n-fold ring distributions of amorphous Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST) (green) and amorphous Ti0.4Sb2Te3 (TST) (red). The four-membered ABAB rings are highlighted: A=(Ge and Sb) or (Ti and Sb) and B=Te. Inset shows the respective ABAB ring (containing 1 or 2 Ge (Ti)) number per Ge (Ti) atom. (b) The TEM images of GST, TST, low-concentration Ti doped Sb2Te3 (LTST) and Sb2Te3 (ST) annealed at 250 °C for 2 min. All the scale bars correspond to 200 nm.

Time-dependent in situ electron beam irradiation experiment confirms this nucleation-dominated mechanism for the crystallization of a-TST (Supplementary Fig. 6). Figure 6b (first row) shows that, in both GST and TST, the grain sizes are on the order of 10–15 nm. In contrast, Fig. 6b (second row) shows that low-concentration Ti-doped ST (LTST) and pure ST exhibit a growth-dominated mechanism with much larger grain size of 50–160 nm. Diminishing grain size is known to increase the interface-area-to-volume ratios to promote hetero-crystallization at the grain boundaries, further speed up the crystallization8.

In summary, a combined experimental and theoretical study reveals a new approach to drastically increase the speed, while decreasing the power, of PCM. These improvements are achieved, without having to rely on any complicated device fabrication and/or programming method, as often being done now. Rather, it is realized by introducing robust TCAMs. We believe the TCAMs may play the role to pin the local structures in both a- and c-ST phases. They act as nucleation centres during the phase transition to avoid substantial atomic rearrangement, which in turn facilitates faster and lower-energy phase transitions. We expect the speed/power to be further increased/decreased significantly on a thorough investigation to optimize the composition of the Ti-Sb-Te. In this regard, a comprehensive model, which is not limited to the possible effect of nucleation centres but can also account for the interactive rearrangement of all the atoms, will be a great help. As the PCM dimension further scales, it is likely that the Ti-Sb-Te alloys will be more advantageous than the Ge-Sb-Te alloys to realize DRAM-like device applications.

Methods

PCM cell fabrication and electrical measurement

T-shaped PCM cell with D=190 (80) nm tungsten plug BEC was fabricated using 0.13 μm CMOS technology. The ~170 nm-thick TST film was deposited by co-sputtering of pure Ti and ST targets, and GST film with the same thickness was deposited by sputtering pure GST target. The ~15 nm-thick TiN and ~300 nm-thick Al films were used as top electrode in both GST and TST cells. All the electrical measurements were performed by using the Keithley 2400C source meter (measuring cell resistance), the Tektronix AWG5002B pulse generator (generating voltage pulse with a minimum width of ~6 ns), the homemade constant current driver (generating current pulse with a maximum magnitude of ~10 mA) and the Tektronix 7054 digital phosphor oscilloscope (measuring transient voltage drop across the cell when current pulse is applied).

Film characterization

The compositions of TST and GST films were measured by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy using a Rigaku RIX 2100 system. For real-time observation of structure transition in pure ST and TST, in situ XRD was performed on 200-nm-thick films (deposited on Si substrate at room temperature) using PANalytical X'Pert PRO diffractometer with a Cu Kα (λ=0.15418, nm) radiation source. TST powders collected from the fragments of thick (1~2 μm) TST amorphous film were used for DSC test to determine Tc and Tm. The 20 nm-thick ST and TST films were deposited on a series of Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) sample supporting grids coated with carbon film. They were annealed at 250 °C for 2 min to get the c-phase. These samples were studied using a FEI Tecnai F20 TEM in the bright field high-resolution TEM mode, selected area electron diffraction mode and scanning TEM mode. Nova 200 Nanolab Focused ion beam was used to fabricate the cross-sectional sample of the PCM cell for the TEM observation.

Ab-initio theoretical simulation

Theoretical investigations employed the density functional theory (DFT)31. The Vienna ab-initio Simulations Package (VASP)32 was used. The projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials33 were used for electron-ion interactions. For the exchange-correlation energies between electrons, the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional34 was used. A 207-atom cubic cell of GST and a 209-atom cubic cell of TST were simulated with periodic boundary conditions by NVT molecular dynamics (MD): to prepare the amorphous phase, first, the system was maintained at 3,000 K for 9 ps. Next, the temperature was lowered to 1,200 K for another 30 ps. The liquid was then quenched to 300 K at a quench rate of −15 K ps−1 to get the amorphous structure, which is maintained at 300 K for another 15 ps. The total simulation time is 114 ps. The energy cutoff is 178 eV and the time step is 3 fs for our MD.

For calculation of formation energy of a Ti atom in c-ST at its possible sites, a 13.01 × 13.01 × 31.26 (Å3) 135-atom supercell was used. A 2 × 2 × 1 k-point mesh was used, but for MD simulation, only the Γ point was used. The formation energy of Ti is given by35:

where Etot is the total energy per supercell with or without Ti. μTi is the chemical potential of Ti and μX is the chemical potential of (Sb, Te) or 0 for X=TiSb (Ti replacing Sb), TiTe (Ti replacing Te) or Tii (Ti intersitial). To maintain a stable ST requires:

where E(ST) is the total energy per formula unit of ST.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Zhu, M. et al. One order of magnitude faster phase change at reduced power in Ti-Sb-Te. Nat. Commun. 5:4086 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5086 (2014).

References

Wuttig, M. Phase-change materials: towards a universal memory? Nature 4, 265–266 (2005).

Atwood, G. Phase-change materials for electronic memories. Science 321, 210–211 (2008).

Kim, I. S. et al. High performance PRAM cell scalable to sub-20 nm technology with below 4F2 cell size, extendable to DRAM applications. Symp. on VLSI Tech. Dig. 203–204Honolulu (2010).

Cheong, B. K. et al. Fast and scalable memory characteristics of Ge-doped SbTe phase change materials. Phys. Status Solidi B 10, 1985–1991 (2012).

Loke, D. et al. Breaking the speed limits of phase-change memory. Science 336, 1566–1569 (2012).

Kohara, S. et al. Structural basis for the fast phase change of: ring statistics analogy between the crystal and amorphous states. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 201910 (2006).

Wang, W. J. et al. Engineering grains of Ge2Sb2Te5 for realizing fast-speed, low-power, and low-drift phase-change memories with further multilevel capabilities. IEDM Tech. Dig. 31.3.1-31.3.4 (San Francisco, (2012).

Wang, W. et al. Enabling universal memory by overcoming the contradictory speed and stability nature of phase-change materials. Sci. Rep. 2, 360 (2012).

Kang, M. J. et al. PRAM cell technology and characterization in 20 nm node size. IEDM Tech. Dig. 3.1.1–3.1.4 (Washington, (2011).

Sasago, Y. et al. Phase-change memory driven by poly-Si MoS transistor with low cost and high-programming gigabyte-per-second throughput. Symp. on VLSI Tech. Dig. 96–97 (Honolulu, (2011).

Yamada, N. et al. Rapid-phase transitions of GeTe-Sb2Te3 pseudobinary amorphous thin films for an optical disk memory. J. Appl. Phys. 65, 2849–2856 (1991).

Akola, J. & Jones, R. O. Structural phase transitions on the nanoscale: The crucial pattern in the phase-change materials Ge2Sb2Te5 and GeTe. Phys. Rev. B 76, 235201 (2007).

Kalikka, J. et al. Nucleus-driven crystallization of amorphous Ge2Sb2Te5: A density functional study. Phys. Rev. B 86, 144113 (2012).

Hegedüs, J. & Elliott, S. R. Microscopic origin of the fast crystallization ability of Ge–Sb–Te phase-change memory materials. Nat. Mater. 7, 399–405 (2008).

Kolobov, A. et al. Understanding the phase-change mechanism of rewritable optical media. Nat. Mater. 3, 703–708 (2004).

Krbal, M. et al. Intrinsic complexity of the melt-quenched amorphous Ge2Sb2Te5 memory alloy. Phys. Rev. B 83, 054203 (2011).

Yin, Y., Sone, H. & Hosaka, S. Characterization of nitrogen-doped Sb2Te3 films and their application to phase-change memory. J. Appl. Phys. 102, 064503 (2007).

Silva, J. L. F. Da, Walsh, A. & Lee, H. Insights into the structure of the stable and metastable (GeTe)m(Sb2Te3)n compounds. Phys. Rev. B 78, 224111 (2008).

Rao, F. et al. Si–Sb–Te materials for phase change memory applications. Nanotechnology 22, 145702 (2011).

Peng, C. et al. Al1.3Sb3Te material for phase change memory application. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 043105 (2011).

Raoux, S. et al. Effect of Al and Cu doping on the crystallization properties of the phase change materials SbTe and GeSb. J. Appl. Phys. 101, 044909 (2007).

Greenaway, D. L. & Nitsche, R. Preparation and optical properties of group IV-VI2 chalcogenides having the CdI2 Structure. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 26, 1445–1458 (1965).

Schmid, B. et al. Synthesis of (Sb2Te3)X(TiTe2)Y superlattices. ICT Thermo 270–272 (2005).

Anderson, T. L. & Krause, H. B. Refinement of the Sb2Te3 and Sb2Te2Se structures and their relationship to nonstoichiometric Sb2Te3−ySey compounds. Acta Cryst B30, 1307–1310 (1974).

Kolobov, A. et al. Vacancy-mediated three-center four-electron bonds in GeTe-Sb2Te3 phase-change memory alloys. Phys. Rev. B 87, 165206 (2013).

Kolobov, A. et al. Why phase-change media are fast and stable: a new approach to an old problem. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 44, 3345–3349 (2005).

Kim, Y. et al. Electronic structures and chemical bonding of TiX2 (X=S, Se, and Te). Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 37, 4878–4883 (1998).

Caravati, S. et al. Coexistence of tetrahedral- and octahedral-like sites in amorphous phase change materials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 171906 (2007).

Shportko, K. et al. Resonant bonding in crystalline phase-change materials. Nat. Mater. 7, 653–658 (2008).

Matsunaga, T. et al. From local structure to nanosecond recrystallization dynamics in AgInSbTe phase-change materials. Nat. Mater. 10, 129–134 (2011).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Zhang, S. B. & Northrup, J. E. Chemical potential dependence of defect formation energies in GaAs: Application to Ga self-diffusion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 2339–2342 (1991).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA09020402), National Key Basic Research Program of China (2013CBA01902, 2011CBA00607, 2011CB932804, 2010CB934300), National Integrate Circuit Research Program of China (2009ZX02023-003), National Natural Science Foundation of China (61076121, 61176122, 61106001, 61261160500, 61376006, 11104109, 11374119), Science and Technology Council of Shanghai (11DZ2261000, 12nm0503701, 12QA1403900, 13ZR1447200, 13DZ2295700). Professor S.Z. was supported by the US Department of Energy under Grant No. DE-SC0002623. The supercomputer time was provided by HPCC at JLU.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Z. and S.L. prepared the film samples and carried out the in situ XRD, DSC, XPS, in situ electron irradiation and TEM experiments and so on. M.Z. and F.R. fabricated the PCM cell samples and carried out electrical measurements. M.X. and X.L. performed the AIMD calculations. F.R., X.L. and S.Z. carried out theoretical analysis and together wrote this paper with help from all co-authors. The project was initiated and conceptualized by F.R. and Z.S.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-6 and Supplementary References (PDF 821 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, M., Xia, M., Rao, F. et al. One order of magnitude faster phase change at reduced power in Ti-Sb-Te. Nat Commun 5, 4086 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5086

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5086

This article is cited by

-

Novel nanocomposite-superlattices for low energy and high stability nanoscale phase-change memory

Nature Communications (2024)

-

In-memory computing based on phase change memory for high energy efficiency

Science China Information Sciences (2023)

-

Simultaneous emulation of synaptic and intrinsic plasticity using a memristive synapse

Nature Communications (2022)

-

A Superlattice Interfacial Phase Change Material with Low Power Consumption

Journal of Electronic Materials (2022)

-

Assessing the Possibilities of NMx(Sb2Te3)1−x Solid Solutions (NM = Noble Metal) for Phase-Change Memory Applications Using High-throughput Calculations

Journal of Electronic Materials (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.