Abstract

Many problems of interest in physics, chemistry and computer science are equivalent to problems defined on systems of interacting spins. However, most such problems require computational resources that are out of reach with classical computers. A promising solution to overcome this challenge is quantum simulation. Several 'analogue' quantum simulations of interacting spin systems have been realized experimentally, where ground states were prepared using adiabatic techniques. Here we report a 'digital' quantum simulation of thermal states; a three-spin frustrated magnet was simulated using a nuclear magnetic resonance quantum information processor, and we were able to explore the phase diagram of the system at any simulated temperature and external field. These results help to identify the challenges for performing quantum simulations of physical systems at finite temperatures, and suggest methods that may be useful in simulating thermal open quantum systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The most challenging aspect of many-body simulation is that the memory and temporal resources often scale exponentially1, rendering many problems of interest intractable by all known classical methods2. A promising solution is quantum simulation3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, in which one quantum system acts as a processor to simulate another physical system (quantum or classical). There are two classes of quantum simulation: 'analog' simulators are typically engineered to simulate a particular class of Hamiltonians15 and to find ground states of nontrivial Hamiltonians adiabatically, whereas 'digital' simulators rely on universal quantum information processors (QIPs)16, capable of implementing a universal set of quantum gate operations17 that can, for instance, efficiently simulate the time evolution of an arbitrary initial state under most physically relevant Hamiltonians18.

Simulations of interacting spin systems19 are of particular importance to many applications, such as modelling magnetism20, solving optimization problems21, and restoring digital images22. Furthermore, understanding the properties of the spin models also offers insights to computational complexity theory23. For example, the ground-state problem of the Ising spin model is known to be an NP-complete problem23,24. This implies that if an efficient algorithm for solving the ground state of the Ising model exists, then it can solve all other problems in the class of NP. This matter is related to the question whether P equals NP, and is a major unsolved problem in computer science; it is one of the Millennium problems selected by the Clay Mathematics Institute25.

In a series of recent experiments3,4,5,6,7 based on adiabatic methods24, great progress in the quantum simulation of spin systems has been made using several physical implementations. These experiments are limited to studying ground-state properties, and require that the energy gaps along the adiabatic paths are large enough to avoid excitations from the ground states24. In general, the energy gaps cannot be predetermined efficiently26, and the controllability of energy gaps is a subject of controversy27. Therefore, the advantage of adiabatic methods over classical methods is not guaranteed in all cases26.

In this paper, we report experimental results for the digital quantum simulation of thermal states of a classical spin system consisting of three antiferromagnetically coupled Ising spins. The ground state of this system is highly degenerate, leading to frustration. A pseudo external field is included in the simulations as an adjustable parameter in probing the variations of the physical properties of the spin system against the changes in the simulated temperature. The experimental implementation was performed using a seven qubit nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) quantum information processor, where four of the nuclear spins were employed for the simulation. We focussed on simulating the total magnetization and the entropy of the Ising spin system. In both cases, the experimental results agree qualitatively with theoretical predictions, and quantitative deviations from theory are analysed with respect to several error sources. A simple decoherence model is found to account for a large portion of the error.

Results

Digital quantum simulation of thermal states

At finite temperatures, all the equilibrium thermodynamic properties of spin systems can be obtained by determining the partition function , which falls into the complexity class sharp-P, or #P (ref. 28) rather than NP. However, if an efficient algorithm for evaluating partition functions exists, then the ground-state properties of the corresponding spin systems can also be determined efficiently. Therefore, the problem of determining partition functions is at least as hard as the NP-problems, that is, it is NP-hard28.

In practice, partition functions cannot be computed efficiently, except for some simple cases such as 1D spin chains20. For classical spins, the classical Metropolis algorithm29 provide a means for generating the Gibbs probability distributions20, through the construction of Markov chains with Monte Carlo methods30. For quantum systems, the quantum generalization of the Metropolis algorithm has been found31,32. However, Markov chain-based methods, similar to the adiabatic methods, are limited to the cases where the Markov-matrix gaps cannot be too small to achieve convergence33. Particularly, for frustrated spin systems19, Metropolis sampling can result in ensembles trapped in local minima. In these cases, methods for direct encoding of the Gibbs distribution into the states of the qubits would be more efficient34,35. This is the key issue that motivates this experimental work.

Using a digital quantum simulator, the experiments we present are able to explore the full phase diagram of the system's thermal states as a function of temperature and magnetic field. Well-developed NMR techniques for quantum information processing36,37 provide convenient experimental methods to implement a universal set of single-qubit and multiple-qubit gates for building quantum circuits.

Coherent encoding of thermal states

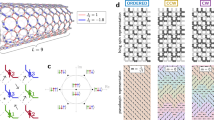

Here we report a digital quantum simulation of the finite-temperature properties of a three-spin frustrated Ising magnet (Fig. 1), using a four-qubit QIP based on NMR. The frustrated magnet exhibits a rich phase diagram of the total magnetization as a function of temperature and magnetic field, and we experimentally probe various distinct features of the system. The phenomenon of geometric frustration38,39 is an interesting topic in condensed matter physics40. For example, materials such as water ice that exhibit geometric frustration cannot be completely frozen, which renders the entropy finite at zero temperature. Recently, the same three-spin magnet at zero temperature was simulated by trapped ions5,6. Our work extends quantum simulation of this system to finite temperatures, using methods that may be generalized for simulating quantum systems in contact with a thermal environment.

(a) Theoretical phase diagram of the magnetization. The units of the axes are kB and Θ for temperature and external field, respectively. The white dashed line parallel to the h-axis denotes T=1/β=1/11, which corresponds to the experimental data shown in Fig. 3. (b) All possible configurations of a three-spin frustrated Ising magnet at zero temperature and zero magnetic field. The ground state is sixfold degenerate, leading to a non-zero entropy. (c) Quantum circuit diagram for preparing and measuring the CETS |Ψβ defined in equation (1) from the initial state |0000

defined in equation (1) from the initial state |0000 . The unitary gates are Ux=R(θx), Uy=R(θy), Uz=R(θz−θy), U0=R(θ0), U1=R(θ1−θ0) and U2=R(θ2−2θ1+θ0), where R(θ)=e−iθY and Y denotes the y-component of the Pauli matrices. The explicit expressions for the angles as functions of β, h and Θ are given in the Supplementary Methods. The upper qubit q0 serves as a probe for measuring the physical observables. H indicates a Hadamard gate, and UM is the operator corresponding to the observable being measured.

. The unitary gates are Ux=R(θx), Uy=R(θy), Uz=R(θz−θy), U0=R(θ0), U1=R(θ1−θ0) and U2=R(θ2−2θ1+θ0), where R(θ)=e−iθY and Y denotes the y-component of the Pauli matrices. The explicit expressions for the angles as functions of β, h and Θ are given in the Supplementary Methods. The upper qubit q0 serves as a probe for measuring the physical observables. H indicates a Hadamard gate, and UM is the operator corresponding to the observable being measured.

The algorithm implemented here prepares a coherent encoding of a thermal state (CETS) on a quantum register34,35,

which is a pure state (a pseudo-pure state41 in the NMR experiment) with amplitudes  equal to the square roots of the corresponding thermal Gibbs probabilities associated with the eigenstate |φk

equal to the square roots of the corresponding thermal Gibbs probabilities associated with the eigenstate |φk of Hamiltonian H. Here β=1/T (kB=1), and

of Hamiltonian H. Here β=1/T (kB=1), and  is the partition function. The CETS, therefore, contains the same information as the thermal density matrix

is the partition function. The CETS, therefore, contains the same information as the thermal density matrix

of the simulated system. ρth can be directly obtained from the CETS state |Ψβ by artificially 'decohering' the off-diagonal elements of the CETS density matrix |Ψβ

by artificially 'decohering' the off-diagonal elements of the CETS density matrix |Ψβ

Ψβ| (ref. 35). In our implementation, we measure the diagonal elements of the CETS density matrix and do not engineer decoherence.

Ψβ| (ref. 35). In our implementation, we measure the diagonal elements of the CETS density matrix and do not engineer decoherence.

The number of quantum gates needed for this method35 of preparing the CETS is linear in the number of spins for one-dimensional systems and sub-exponential in two dimensions, but is exponential for the general cases that correspond to NP-problems. Nonetheless, the efficiency of the algorithm is independent of the simulated temperature and not limited by the small-gap problem encountered in the Markov-Chain Monte Carlo algorithms. This provides an advantage for simulating the low-temperature properties of frustrated spin systems. Furthermore, although these algorithms can at most yield a quadratic speedup for simulating the most general thermal states35, the subclass of the CETS which can be created efficiently on a quantum computer can serve as a 'heat bath'42 and may yield an exponential speedup over classical methods when simulating the dynamics of open quantum systems43. Our goal is to demonstrate that the CETS for a system showing geometric frustration can be prepared in the laboratory precisely enough to extract useful thermodynamic information.

Simulation of a frustrated magnet subject to an external field

In this experiment, three qubits encode the CETS of a triangle plaquette of Ising spins with equal couplings Θ, at temperature T and subject to a global magnetic field h. A fourth ancilla qubit is used to probe the physical properties of the CETS by measuring the set of diagonal Pauli operators, so that the spin magnetizations and correlations can be extracted. These measurements are sufficient to determine the partition function  , from which any thermodynamic quantity of interest, such as entropy S, can be calculated.

, from which any thermodynamic quantity of interest, such as entropy S, can be calculated.

The Hamiltonian of the frustrated magnet subject to an external field is given by19,39

where  is the

is the  Pauli matrix of the spin i. For Θ>0, the coupling is antiferromagnetic, and the spins tend to minimize energy by pointing in opposite directions. The external field h, however, tends to force the spins to align. A finite temperature T serves to mix up these tendencies. These competing factors give rise to a rich phase diagram shown in Fig. 1a. For example, at low temperature and near some critical values of the external field h=−2Θ, 0 and 2Θ (we set Θ=1 in the following), there are crossover points where the spin configuration, and hence the total magnetization, changes abruptly. Near h=0, the ground state is fully frustrated with a sixfold degeneracy, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. This means that, unlike ordinary materials, the entropy and heat capacity of the spin system remain finite as T→0.

Pauli matrix of the spin i. For Θ>0, the coupling is antiferromagnetic, and the spins tend to minimize energy by pointing in opposite directions. The external field h, however, tends to force the spins to align. A finite temperature T serves to mix up these tendencies. These competing factors give rise to a rich phase diagram shown in Fig. 1a. For example, at low temperature and near some critical values of the external field h=−2Θ, 0 and 2Θ (we set Θ=1 in the following), there are crossover points where the spin configuration, and hence the total magnetization, changes abruptly. Near h=0, the ground state is fully frustrated with a sixfold degeneracy, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. This means that, unlike ordinary materials, the entropy and heat capacity of the spin system remain finite as T→0.

For any given value of temperature and magnetic field, the CETS |Ψβ can be prepared with a quantum circuit of constant size, as shown in Fig. 1c. The three lower qubits, q1, q2 and q3, initialized into the |000

can be prepared with a quantum circuit of constant size, as shown in Fig. 1c. The three lower qubits, q1, q2 and q3, initialized into the |000 state, are the register qubits used to encode the CETS. We use the phase kick-back method for readout17 by introducing a fourth 'probe' qubit q0, exploiting the fact that all spin–spin (J) couplings are well resolved for this qubit (see Methods section). All information contained in the CETS is gained by measurements on the probe qubit, so that we avoid experimental difficulties with direct readout of qubits q1−q3 owing to poor spectral resolution of certain spin–spin couplings. We did, however, implement direct state tomography of the register qubits for certain states to compare readout methods and to quantify errors (see Discussion and Methods), but we found this to be generally unreliable for arbitrary states. All elements of an arbitrary density matrix can be reconstructed using the phase kick-back method, if the density matrix is expanded in the product operator basis44.

state, are the register qubits used to encode the CETS. We use the phase kick-back method for readout17 by introducing a fourth 'probe' qubit q0, exploiting the fact that all spin–spin (J) couplings are well resolved for this qubit (see Methods section). All information contained in the CETS is gained by measurements on the probe qubit, so that we avoid experimental difficulties with direct readout of qubits q1−q3 owing to poor spectral resolution of certain spin–spin couplings. We did, however, implement direct state tomography of the register qubits for certain states to compare readout methods and to quantify errors (see Discussion and Methods), but we found this to be generally unreliable for arbitrary states. All elements of an arbitrary density matrix can be reconstructed using the phase kick-back method, if the density matrix is expanded in the product operator basis44.

The probe is shown as the upper qubit in Fig. 1c and is prepared in a superposition state  just prior to readout. A controlled-UM gate is then applied to the joint probe-CETS system to measure observables

just prior to readout. A controlled-UM gate is then applied to the joint probe-CETS system to measure observables  UM

UM =

= Ψβ|UM|Ψβ

Ψβ|UM|Ψβ . Here

. Here  UM

UM is proportional to the coherent part of the reduced density matrix of the probe qubit obtained by tracing over qubits q1−q3:

is proportional to the coherent part of the reduced density matrix of the probe qubit obtained by tracing over qubits q1−q3:

UM

UM is extracted from the NMR signal of the probe qubit after application of the controlled-UM gate. A Hamiltonian of the classical Ising type (i.e. equation (3)) leads to a purely diagonal thermal state density matrix. Hence, by measuring the set of observables that span the diagonal matrix elements,

is extracted from the NMR signal of the probe qubit after application of the controlled-UM gate. A Hamiltonian of the classical Ising type (i.e. equation (3)) leads to a purely diagonal thermal state density matrix. Hence, by measuring the set of observables that span the diagonal matrix elements,

the thermal state density matrix ρth can be reconstructed (see equation (6) below).

Experimental results for magnetization and entropy

In the experiment, we use the four carbon spins of 13C-labelled trans-crotonic acid dissolved in d6-acetone as the four qubit register41. The structure of the molecule and spin Hamiltonian parameters are shown in Fig. 2a and Table 1, respectively. Using well-known quantum gate decompositions45,46, we first decomposed the controlled-unitary operations in Fig. 1b,c into single-qubit rotations and controlled-NOT gates (Supplementary Fig. S1), where the elementary gates can be implemented using a combination of radio-frequency (RF) pulses and evolutions under the spin–spin J-couplings (for example, see refs 36,37). The NMR pulse sequences were further simplified to minimize the number of pulses needed, resulting in the pulse sequence shown in Fig. 2b for preparing the CETS, and the sequence shown in Fig. 2c for measuring  UM

UM =

= Z1Z2Z3

Z1Z2Z3 , for example. In the CETS preparation sequence, RF phase shifts are exploited to implement the variable angle

, for example. In the CETS preparation sequence, RF phase shifts are exploited to implement the variable angle  -rotations φk from which we construct the variable angle qubit rotations required by the algorithm. Hence, the pulse sequences for every (h,T) point are identical up to RF phase shifts; the phase shifts are implemented with high precision in NMR (resolution ~104 per rad), and require no evolution time.

-rotations φk from which we construct the variable angle qubit rotations required by the algorithm. Hence, the pulse sequences for every (h,T) point are identical up to RF phase shifts; the phase shifts are implemented with high precision in NMR (resolution ~104 per rad), and require no evolution time.

(a) The molecular structure of carbon-13-labelled trans-crotonic acid. C1–C4 label 13C spins, and M, H1 and H2 label protons. (b,c) Pulse sequences for (b) preparing the CETS on qubits q1−q3, and (c) measuring observable Z1Z2Z3 via the top 'probe' qubit q1 (refocussing pulses are omitted in both circuits for clarity). The three carbons C2–C4 are the CETS register qubits q1−q3, and C1 serves as the probe qubit. The RF phase shifts are determined by  , where the rotation angles θk (k=x, y, z, 0, 1, 2) are listed in Supplementary Methods.

, where the rotation angles θk (k=x, y, z, 0, 1, 2) are listed in Supplementary Methods.

The experimental results are summarized as follows: the diagonal elements of the density matrix corresponding to the CETS are determined by measuring the set of diagonal Pauli operators (equation (5)) for a range of simulated temperatures and external fields. Figure 3 shows example NMR spectra of the probe qubit (C1). Figure 3a shows the NMR spectra of C1 obtained by a π/2 readout pulse, when the system is in the labelled pseudo-pure state41 ρs=00 σz0000 (red) and a reference state  (blue), respectively, where

(blue), respectively, where  is the identity matrix, 0≡|0

is the identity matrix, 0≡|0

0|, and the order of qubits is given by: M, H1, H2, C1, C2, C3, C4. We employ the deviation density matrix formalism47 throughout this work. Figures 3b,c show spectra corresponding to measurements of

0|, and the order of qubits is given by: M, H1, H2, C1, C2, C3, C4. We employ the deviation density matrix formalism47 throughout this work. Figures 3b,c show spectra corresponding to measurements of  Z1Z2Z3

Z1Z2Z3 in experiment and by simulation, respectively, with β=5, h=−1 (red), 0 (blue), and 1 (black). In each spectrum, only the spectral peaks corresponding to spin M in the state |0

in experiment and by simulation, respectively, with β=5, h=−1 (red), 0 (blue), and 1 (black). In each spectrum, only the spectral peaks corresponding to spin M in the state |0 are shown, as the peaks corresponding to M in state |1

are shown, as the peaks corresponding to M in state |1 are negligibly small. For reference, Fig. 3d shows simulated spectra of C1 corresponding to spin H2 in state |0

are negligibly small. For reference, Fig. 3d shows simulated spectra of C1 corresponding to spin H2 in state |0 (red) and |1

(red) and |1 (blue) with C2-C4 in the state

(blue) with C2-C4 in the state  .

.

(a) Spectra of C1 obtained by π/2 readout pulses when the system is in the labelled pseudo-pure state ρs=00 σz0000 (red) and reference state  (blue), respectively, where

(blue), respectively, where  is the identity matrix, 0≡|0

is the identity matrix, 0≡|0

0| and the qubit order is given by MH1H2C1C2C3C4. All vertical axes have the same scaling (arbitrary units). (b,c) Spectra of C1 for measuring

0| and the qubit order is given by MH1H2C1C2C3C4. All vertical axes have the same scaling (arbitrary units). (b,c) Spectra of C1 for measuring  Z1Z2Z3

Z1Z2Z3 in experiment (b) and by simulation that includes carbon T2 effects (c), with β=5, h=−1 (red), 0 (blue), and 1 (black). In each spectrum, only the peaks corresponding to spin M in the state |0

in experiment (b) and by simulation that includes carbon T2 effects (c), with β=5, h=−1 (red), 0 (blue), and 1 (black). In each spectrum, only the peaks corresponding to spin M in the state |0 are shown, as the peaks corresponding to M in state |1

are shown, as the peaks corresponding to M in state |1 are negligibly small. (d) For reference, simulated spectra of C1 corresponding to spin H2 in state |0

are negligibly small. (d) For reference, simulated spectra of C1 corresponding to spin H2 in state |0 (red) and |1

(red) and |1 (blue) are shown (with C2–C4 in the state

(blue) are shown (with C2–C4 in the state  ).

).

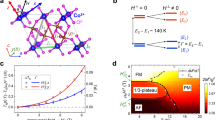

Figure 4a shows the results of measuring the total magnetization Z1+Z2+Z3 over a range of fields −5≤h≤5 at a low temperature, β=11. The raw experimental results are in good agreement with a numerical simulation of the NMR experiments that takes into account the decoherence of the nuclear spins during the computation. The magnetization is seen to change in steps as the simulated field is varied, with critical points located at h=±2, and 0, in agreement with the phase diagram in Fig. 1a. The data shown in Figs 4a–d labelled as black stars are rescaled based on a simple depolarization channel decoherence model that assumes uniform error rates for all qubits and has no free parameters (see Supplementary Methods). This rescaling partially removes errors due to decoherence of the probe qubit during the readout step, and clearly improves the agreement with theory. A slight asymmetry of the experimental results with respect to the sign of h is evident in Figs 4a–d, and may arise from the spin-lattice (T1) relaxation of the carbon spins, which was not included in the numerical simulations (see Methods).

(a) Total magnetization Z1+Z2+Z3 as a function of magnetic field h for a low temperature, β=11. The theoretical result is shown by the black solid curve. The experimental data (red open circles) is plotted together with numerical simulation results (blue crosses) that include effects of carbon T2 and proton T1. The points labelled by black stars are obtained from the experimental data by the use of a simple decoherence model to partially remove the effects of decoherence (see Supplementary Methods). Error bars are estimated from the uncertainty of the spectral fitting parameters in experimental data analysis. The sharp changes in magnetization show the phase transitions, and the regions around the critical points h=±2,0 are enlarged as figures (b–d). (e–j) Surface plots showing the theoretical values for total magnetization (e) Z1+Z2+Z3 and spin correlations (f) Z1Z2+Z2Z3+Z1Z3 and (g) Z1Z2Z3, where 1≤β≤11 and −1≤h≤1. The corresponding experimental values are shown in (h–j), respectively, with experimental uncertainties indicated (error bars in red).

Spin correlation functions were also probed systematically for a range of the simulated temperatures and external fields. Selected results are shown in Fig. 4e. From this data, the thermal state density matrix may be constructed for any (h,T) point, subject to the normalization condition Tr(ρth)=1:

where ai≡ Zi

Zi /8, bjk≡

/8, bjk≡ ZjZk

ZjZk /8, and c≡

/8, and c≡ Z1Z2Z3

Z1Z2Z3 /8, and the expectation values here represent only the real-valued parts (the imaginary parts are zero in theory but non-zero in experiment due to errors; see Discussion). With complete knowledge of ρth, all macroscopic thermodynamic observables can be determined for an ensemble of frustrated magnets. In this study, we are particularly interested in obtaining the entropy,

/8, and the expectation values here represent only the real-valued parts (the imaginary parts are zero in theory but non-zero in experiment due to errors; see Discussion). With complete knowledge of ρth, all macroscopic thermodynamic observables can be determined for an ensemble of frustrated magnets. In this study, we are particularly interested in obtaining the entropy,

which acts as a signature of frustration. Because of its nonlinearity, S is expected to be more sensitive to experimental errors than quantities that depend linearly on ρth such as magnetization.

Figure 5a shows the experimental results for S as a function of the simulated magnetic field h in the low-temperature regime (β=11), compared with theory. Sharp changes in S are observed near the same critical points seen in the magnetization data. The larger values of S in the region |h|<2 compared with the outer region |h|>2 indicate the preference of anti-ferromagnetism leading to frustration. A peak at h=0, indicating maximal degeneracy of the ground state, is seen in both the experiment and theory. For the outer region |h|>2, the external field is strong enough to polarize the magnet leading to a theoretical entropy of zero. However, both the raw and rescaled experimental results yield finite values of S. This discrepancy is mainly due to decoherence of the nuclear spin qubits during the computation, as expected from the durations of the pulse sequences (see Discussion, Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Fig. S2), and confirmed by numerical simulation results. The rescaled results are closer to theory, but are still offset significantly, because the actual errors are not uniform across qubits and are not independent of which observable is measured (the readout pulse sequences have different durations). The surface plots in Figs 5b–d show S as a function of h and β in theory (b), simulation (c), raw experimental data (d), and rescaled experimental data (e). The role of increasing temperature is to 'wash out' the competition between the antiferromagnetic couplings, so that sharp crossovers are not observed in theory or experiment as β is decreased.

(a) Entropy S as a function of magnetic field h at low temperature, β=11. The experimental data (open circles) is plotted together with numerical simulation results (crosses) that include effects of carbon T2 and proton T1. The theoretical result is shown by the solid curve. The sharp changes of S around h=±2,0 indicate the phase transitions. The points labelled by black stars are obtained from the experimental data by the use of a simple decoherence model to partially remove the effects of decoherence. (b–e) Surface plots of entropy as a function of −1≤h≤1 and 1≤β≤11 in theory (b), numerical simulation (c) and experiment (d). The rescaled experimental results are shown in (e).

Discussion

In the following, we discuss in more detail the sources of error affecting our NMR implementation. For example, consider as a benchmark state the CETS corresponding to β=11 and h=5, where the Ising spins are polarized. We numerically simulated the CETS preparation pulse sequence both including and not including the nuclear spin T2 process, and also measured the experimental density matrix using direct state tomography. The results are summarized in Fig. 6. The error bars on the data measured by direct state tomography of the CETS are much larger than for phase kick-back; this is due to the inability to fully resolve all J-couplings on spins C2–C4. Figure 6g shows the imaginary elements present in the numerical simulation that does not include T2 effects. The imaginary elements on the diagonal are zero in both simulations (g) and (h), but are non-zero in experiment. These elements are due to phase distortions of the readout signals with respect to the reference signal. The average of the root-mean-square of all the imaginary elements on the diagonal, relative to the norm of the real-valued diagonal elements, is 0.077 in experiment and 0.034 in the simulation (not shown) of the full experiment (preparation+readout) that includes T2. Hence, the overall magnitude of this error is small, and is infact related to the output state fidelity in a second order way, because for a small phase error δ the imaginary elements will be proportional to sin(δ) δ whereas the fidelity will be proportional to cos(δ)

δ whereas the fidelity will be proportional to cos(δ) 1−δ2. For the real-valued data, note the qualitative correspondence between (c) and (e), the simulation results including T2 and the phase kick-back results.

1−δ2. For the real-valued data, note the qualitative correspondence between (c) and (e), the simulation results including T2 and the phase kick-back results.

(a–e) From left to right, the five columns show the real parts of the density matrices (a) in theory, (b) by simulation without carbon T2, (c) by simulation including carbon T2, (d) in experiment by full state tomography, and (e) in experiment using the phase kick-back readout. The first three columns show the state just after the CETS preparation. The bottom rows (f–j) show the corresponding imaginary parts of the density matrices. Compared with the theoretical result, the state fidelities from the simulation without T2, simulation with T2, state tomography and phase kick-back method are 0.919, 0.798, 0.782±0.042 and 0.602±0.002, respectively. Here we define the fidelity of a measured state ρ as Tr(ρρ0), where ρ0 denotes the ideal state. The errors in phase kick-back are estimated from the uncertainty of the fitting parameters and are less than 0.01, so are not shown here. For the full state tomography results shown in (d) and (i) (measured directly using the spectra of C2–C4), the amplitude of each peak is measured by integrating over a range of frequency, because the imperfect resolution of some peaks renders a spectral fit unreliable. The peak integration range is typically 0.40 Hz. The average uncertainty of each measured matrix element is ± 0.035 (d) and ± 0.051 (i), consistent with the greater scatter seen in the data compared to the phase kick-back results. This illustrates the benefit obtained from using C1, which has well-resolved spectra, as the probe qubit.

Now, we use the state correlation fidelity defined as Tr(ρρ0) for quantitative analysis, where ρ0 is the ideal density matrix and ρ is either the result of numerical simulation of the NMR experiment or experimental data. The state correlation obtained from numerical simulation of the CETS preparation without including the T2 process is 0.92, where the 8% infidelity is due to undesired evolution under J-couplings, finite pulsewidth and off-resonance effects, all of which are minimized by our refocussing scheme but are not removed perfectly. Including T2 in the simulation reduces the state correlation further to 0.80. The state correlation obtained from experimental state tomography is 0.782±0.042, from which we can estimate that the errors from experimental pulse imperfections account for at most a few percent of the infidelity. The total number of pulses in the CETS preparation sequence (including refocussing pulses) is 104, suggesting an average error per pulse  . This relatively low error rate due to non-ideality of pulses is in accord with other recent NMR QIP experiments37,48, and shows that we are able to implement standard qubit-selective pulses and coupling gates with high fidelities. Performing readout on the same CETS using the probe qubit phase kick-back method (for example, Fig. 1c) results in a state correlation of 0.602±0.002. This is reasonable because of the durations of the additional readout circuits (ranging from 20 to 410 ms) that cause

. This relatively low error rate due to non-ideality of pulses is in accord with other recent NMR QIP experiments37,48, and shows that we are able to implement standard qubit-selective pulses and coupling gates with high fidelities. Performing readout on the same CETS using the probe qubit phase kick-back method (for example, Fig. 1c) results in a state correlation of 0.602±0.002. This is reasonable because of the durations of the additional readout circuits (ranging from 20 to 410 ms) that cause  UM

UM to decay under T2. The aforementioned rescaling procedure, when applied to the density matrix measured via the probe qubit, gives a modified state correlation of 0.881±0.034. This is consistent with the fidelity we would expect from the experiment with the effects of T2 removed. The rescaled entropy results plotted in Fig. 5a are roughly consistent with this level of infidelity; for example, if one takes the ideal density matrix at β=11 and h=5 and scales all the observables (ai, bjk, c in equation (6)) by a factor of 0.88, the corresponding entropy would be 0.54 rather than ~0. However, the observables measured in our experiment are not all scaled by the same factor, because of different durations of the readout sequences and to deviation of the actual error process from the simple uniform-error model. The rescaled experimental entropy, averaged over its values at h=±5, is 0.93±0.01.

to decay under T2. The aforementioned rescaling procedure, when applied to the density matrix measured via the probe qubit, gives a modified state correlation of 0.881±0.034. This is consistent with the fidelity we would expect from the experiment with the effects of T2 removed. The rescaled entropy results plotted in Fig. 5a are roughly consistent with this level of infidelity; for example, if one takes the ideal density matrix at β=11 and h=5 and scales all the observables (ai, bjk, c in equation (6)) by a factor of 0.88, the corresponding entropy would be 0.54 rather than ~0. However, the observables measured in our experiment are not all scaled by the same factor, because of different durations of the readout sequences and to deviation of the actual error process from the simple uniform-error model. The rescaled experimental entropy, averaged over its values at h=±5, is 0.93±0.01.

It is possible to reduce the duration of the pulse sequences, and thus the effects of decoherence, by using numerically derived optimal control pulses49 to implement the circuit unitaries. Recent NMR QIP experiments have illustrated the use of this technique50,51, which allows the unitaries to be implemented in a nearly time-optimal manner. However, these techniques require full classical simulation of the unitary dynamics, rendering straightforward application of the approach impractical for large numbers of qubits. On the other hand, the pulse sequences implemented in this work were derived in a completely scalable fashion37. To achieve high fidelity in larger NMR processors such as are possible in the solid-state52,53, it may be necessary to achieve a hybrid of the two methods that is inherently scalable but uses optimal control on subsystems of fixed qubit number51.

In summary, our NMR implementation of the CETS preparation and readout uses a scalable quantum gate decomposition and obtains the principal thermodynamic features of the three-spin frustrated Ising magnet. We explored the phase diagram for a range of simulated temperatures and global fields, studying the competition between the antiferromagnetic couplings and the polarizing field. The crossover points were correctly captured in both magnetization and entropy, and the increases in entropy signifying frustration were obtained, including the peak in entropy at low temperature and zero field. The experimental results were found to agree very well with numerical simulations of the NMR experiment. The discrepancies between these results and the ideal theory results are mainly due to to the attenuation of expectation values caused by decoherence during the computation, and, to a lesser extent, the imperfect design of the refocussing pulse sequences. Experimental pulse imperfections gave a relatively small contribution to the total error, verifying the high level of control achievable in NMR and suggesting that control is not a fundamental limitation for implementing similar algorithms in larger Hilbert spaces. We believe that techniques used here can be adapted to other physical systems used to realized QIPs, such as nitrogen vacancy centres in diamond16. The ability to deterministically prepare a CETS on a subset of qubits in a larger quantum simulation provides a new method, in principle, to simulate contact between a quantum system of interest and a heat bath at arbitrary temperature T. This may provide an economical means for simulating open quantum systems, particularly for thermal states of systems with multifold degenerate ground states.

Methods

NMR implementation

For the NMR implementation, we used 13C-labelled trans-crotonic acid dissolved in d6-acetone, which forms a seven-qubit register; the four qubits in this experiment correspond to the four carbon spins, and the three proton spins are not directly involved after the preparation of the pseudo-pure state41. The experiments were carried out on a 700-MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker DRX). The structure of the molecule and the Hamiltonian parameters of the seven spin qubits are shown in Fig. 2a, with the spin Hamiltonian given by

where νj and  denote the chemical shift and

denote the chemical shift and  Pauli matrix of spin j, respectively, and Jkl denotes the scalar coupling between spins k and l.

Pauli matrix of spin j, respectively, and Jkl denotes the scalar coupling between spins k and l.

In the experiment, single-spin  -axis rotations are implemented either through the evolution of the chemical shifts in the Hamiltonian or by RF phase shifts37. Rotations along x- and y-axes are implemented by standard Isech and Hermite-shaped frequency selective RF pulses for spins M and C1-C4, and numerically optimized GRAPE pulses37,49 for the manipulation of H1 and H2 during the pseudo-pure state preparation. Judicious placement of spin-selective refocussing pulses allows us to construct the desired J-coupling evolutions between neighbouring qubits. A custom-built software compiler optimizes the pulse sequences for highest unitary fidelity by minimizing the effects of finite pulsewidth and off-resonance errors as well as unwanted coupling evolutions, using methods that scale polynomially in the number of qubits37. Refocussing pulses are not shown in Fig. 2b,c).

-axis rotations are implemented either through the evolution of the chemical shifts in the Hamiltonian or by RF phase shifts37. Rotations along x- and y-axes are implemented by standard Isech and Hermite-shaped frequency selective RF pulses for spins M and C1-C4, and numerically optimized GRAPE pulses37,49 for the manipulation of H1 and H2 during the pseudo-pure state preparation. Judicious placement of spin-selective refocussing pulses allows us to construct the desired J-coupling evolutions between neighbouring qubits. A custom-built software compiler optimizes the pulse sequences for highest unitary fidelity by minimizing the effects of finite pulsewidth and off-resonance errors as well as unwanted coupling evolutions, using methods that scale polynomially in the number of qubits37. Refocussing pulses are not shown in Fig. 2b,c).

The effects of pulse errors due to RF inhomogeneity over the spin ensemble are reduced by implementing an RF selection technique, that is, a spatial selection of molecules in a region of high RF homogeneity. The linewidth, and therefore the coherence of the ensemble qubits, is also improved41,54. The four carbon spins, initialized in the state 0000, are used to prepare and measure the CETS, where C1 is the probe qubit, and C2–C4 are the register qubits used to simulate the frustrated magnet. The CETS |Ψβ is prepared by the pulse sequence shown in Fig. 2b. The NMR signal of C1 is acquired after the controlled-UM gate is applied. The controlled-UM is implemented by combining phase-flip and SWAP gate operations, and is further decomposed into nearest-neighbour coupling evolutions and single spin rotations. As an example, Fig. 2c illustrates the pulse sequence for the observable Z1Z2Z3.

is prepared by the pulse sequence shown in Fig. 2b. The NMR signal of C1 is acquired after the controlled-UM gate is applied. The controlled-UM is implemented by combining phase-flip and SWAP gate operations, and is further decomposed into nearest-neighbour coupling evolutions and single spin rotations. As an example, Fig. 2c illustrates the pulse sequence for the observable Z1Z2Z3.

As indicated in equation (4),  UM

UM is encoded in the coherent part of the probe qubit (C1) state. In the spectra of the probe qubit, the coherence is distributed among 26=64 resonance peaks, each of which corresponds to a particular eigenstate of the remaining 6 qubits M, H1, H2, C2-C4. The intensities of these peaks are obtained by a precise spectral fitting procedure48.

is encoded in the coherent part of the probe qubit (C1) state. In the spectra of the probe qubit, the coherence is distributed among 26=64 resonance peaks, each of which corresponds to a particular eigenstate of the remaining 6 qubits M, H1, H2, C2-C4. The intensities of these peaks are obtained by a precise spectral fitting procedure48.

Since σz=0−1 with 1≡|1

1| , the 64 peaks are divided into two antiphase multiplets corresponding to the two eigenstates of H2. We may, for example, choose the group marked by the H2 state 0. By adding the amplitudes of the 8 peaks corresponding to the state

1| , the 64 peaks are divided into two antiphase multiplets corresponding to the two eigenstates of H2. We may, for example, choose the group marked by the H2 state 0. By adding the amplitudes of the 8 peaks corresponding to the state  ,

,  UM

UM is obtained. As a reference signal to define the phases and magnitudes of the signals acquired to measure

is obtained. As a reference signal to define the phases and magnitudes of the signals acquired to measure  UM

UM , we use the signal of C1 corresponding to the state

, we use the signal of C1 corresponding to the state  obtained by a π/2 readout pulse applied to C1 from the initial pseudo-pure state ρs (see Fig. 3).

obtained by a π/2 readout pulse applied to C1 from the initial pseudo-pure state ρs (see Fig. 3).

T1 relaxation of the proton spins

In preparing the CETS and measuring  UM

UM , the proton spins M, H1 and H2 ideally remain in the state 00 σz. We measured the decay of the state

, the proton spins M, H1 and H2 ideally remain in the state 00 σz. We measured the decay of the state  to estimate the effect of the protons' T1 relaxation process on the measurement of the CETS. The state

to estimate the effect of the protons' T1 relaxation process on the measurement of the CETS. The state  is prepared from ρs through phase cycling. After a variable delay, a π/2 readout pulse for H2 is applied. The intensity of the signal against the delay time is shown in Supplementary Fig. S3, with a fit yielding a relaxation time of 2.9 s. This relaxation was included along with the carbon T2 decays in the numerical simulations of the NMR experiment.

is prepared from ρs through phase cycling. After a variable delay, a π/2 readout pulse for H2 is applied. The intensity of the signal against the delay time is shown in Supplementary Fig. S3, with a fit yielding a relaxation time of 2.9 s. This relaxation was included along with the carbon T2 decays in the numerical simulations of the NMR experiment.

T1 relaxation of the carbon spins

Considering the durations of the experiments listed in Supplementary Table S1 in Supplementary Information, the T1 relaxation of the carbon spins may explain the asymmetry of fidelity, with respect to the sign of h in Figs 3a–d, in the main text. In principle, the T1 relaxation could affect the CETS states differently. We take states of the register qubits |000 and |111

and |111 as examples, where the qubit ordering is C2–C3. In the experiments, RF selection was used to improve the fidelity of pulses. The pulse sequence of the RF selection effectively operates as a π pulse to spin M in the initial state

as examples, where the qubit ordering is C2–C3. In the experiments, RF selection was used to improve the fidelity of pulses. The pulse sequence of the RF selection effectively operates as a π pulse to spin M in the initial state  , the state from which the labelled pseudo-pure state ρs was prepared. Hence, the starting point of the experiments is the pseudo-pure state −ρs. The state of the register qubits |000

, the state from which the labelled pseudo-pure state ρs was prepared. Hence, the starting point of the experiments is the pseudo-pure state −ρs. The state of the register qubits |000 corresponds to a deviation density matrix in the NMR experiment

corresponds to a deviation density matrix in the NMR experiment  , and |111

, and |111 corresponds to

corresponds to  . Although we have not checked by explicit simulations or experiments, it is reasonable to speculate that ρ000 decays faster than ρ111.

. Although we have not checked by explicit simulations or experiments, it is reasonable to speculate that ρ000 decays faster than ρ111.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Zhang, J. et al. Digital quantum simulation of the statistical mechanics of a frustrated magnet. Nat. Commun. 3:880 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1860 (2012).

References

Kohn, W. Nobel lecture: electronic structure of matter-wave functions and density functionals. Rev. Mod. Phys. 71, 1253–1266 (1999).

Feynman, R. P. Simulating physics with computers. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 21, 467–488 (1982).

Peng, X., Du, J. & Suter, D. Quantum phase transition of ground-state entanglement in a Heisenberg spin chain simulated in an NMR quantum computer. Phys. Rev. A 71, 012307 (2005).

Friedenauer, A. et al. Simulating a quantum magnet with trapped ions. Nat. Phys. 4, 757–761 (2008).

Kim, K. et al. Quantum simulation of frustrated Ising spins with trapped ions. Nature 465, 590–593 (2010).

Edwards, E. et al. Quantum simulation and phase diagram of the transverse-field Ising model with three atomic spins. Phys. Rev. B 82, 060412 (2010).

Ma, X.- S. et al. Quantum simulation of the wavefunction to probe frustrated Heisenberg spin systems. Nature Phys. 7, 1–7 (2011).

Lanyon, B. P. et al. Towards quantum chemistry on a quantum computer. Nat. Chem. 2, 106–111 (2010).

Gerritsma, R. et al. Quantum simulation of the Dirac equation. Nature 463, 68–71 (2010).

Weimer, H., Müller, M., Lesanovsky, I., Zoller, P. & Büchler, H. P. A Rydberg quantum simulator. Nat. Phys. 6, 382–388 (2010).

Barreiro, J. T. et al. An open-system quantum simulator with trapped ions. Nature 470, 486–491 (2011).

Struck, J. et al. Quantum simulation of frustrated classical magnetism in triangular optical lattices. Science 333, 996–999 (2011).

Li, Z. et al. Solving quantum ground-state problems with nuclear magnetic resonance. Sci. Rep. 1, 88 (2011).

Lanyon, B. P. et al. Universal digital quantum simulation with trapped ions. Science 334, 57–61 (2011).

Buluta, I. & Nori, F. Quantum simulators. Science 326, 108–111 (2009).

Ladd, T. D. et al. Quantum computers. Nature 464, 45–53 (2010).

Kaye, P., Laflamme, R. & Mosca, M. An Introduction to Quantum Computing (Oxford University Press, 2007).

Kassal, I. et al. Simulating chemistry using quantum computers. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 62, 185–207 (2011).

Mezard, M., Parisi, G. & Virasoro, M. A. Spin Glass Theory and Beyond (World Scientific, 1987).

Mattis, D. C. & Swendsen, R. H. Statistical Mechanics Made Simple, 2nd edn (World Scientific, 2008).

Young, A. P., Knysh, S. & Smelyanskiy, V. N. Size dependence of the minimum excitation gap in the quantum adiabatic algorithm. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 170503 (2008).

Nishimori, H. & Wong, K. Statistical mechanics of image restoration and error-correcting codes. Phys. Rev. E 60, 132–144 (1999).

Istrail, S. Statistical mechanics, three-dimensionality and NP-completeness: I. Universality of intracatability for the partition function of the Ising model across non-planar surfaces. Proceedings of the Thirty-Second Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of computing 87–96 (2000).

Farhi, E. et al. A quantum adiabatic evolution algorithm applied to random instances of an NP-complete problem. Science 292, 472–475 (2001).

Clay Mathematics institute. http://www.claymath.org/millennium/P_vs_NP/ (2012).

Altshuler, B., Krovi, H. & Roland, J. Anderson localization makes adiabatic quantum optimization fail. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12446–12450 (2010).

Dickson, N. & Amin, M. Does Adiabatic Quantum Optimization Fail for NP-Complete Problems? Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 050502 (2011).

De las Cuevas, G., Dür, W., Van den Nest, M. & Martin-Delgado, M. A. Quantum algorithms for classical lattice models. New J. Phys. 13, 093021 (2011).

Metropolis, N., Rosenbluth, A. W., Rosenbluth, M. N., Teller, A. H. & Teller, E. Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 21, 1087–1092 (1953).

Robert, C. P. & Casella, G. Monte Carlo Statistical Methods, 2nd edn (Springer-Verlag, 2004).

Temme, K. et al. Quantum Metropolis sampling. Nature 471, 87–90 (2011).

Yung, M.- H. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. A quantum-quantum Metropolis algorithm. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 754–759 (2012).

Aldous, D. J. Some inequalities for reversible markov chains. J. Lond. Math. Soc. s2–25, 564–576 (1982).

Lidar, D. & Biham, O. Simulating Ising spin glasses on a quantum computer. Phys. Rev. E 56, 3661–3681 (1997).

Yung, M.- H. et al. Simulation of classical thermal states on a quantum computer: a transfer-matrix approach. Phys. Rev. A 82, 060302 (2010).

Vandersypen, L. M. K. & Chuang, I. L. NMR techniques for quantum control and computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 1037–1069 (2004).

Ryan, C. A. et al. Liquid-state nuclear magnetic resonance as a testbed for developing quantum control methods. Phys. Rev. A 78, 012328 (2008).

Morgan, J. P., Stein, A., Langridge, S. & Marrows, C. H. Thermal ground-state ordering and elementary excitations in artificial magnetic square ice. Nat. Phys. 7, 75–79 (2010).

Wannier, G. Antiferromagnetism. The Triangular Ising Net. Phys. Rev. 79, 357–364 (1950).

Castelnovo, C., Moessner, R. & Sondhi, S. L. Magnetic monopoles in spin ice. Nature 451, 42–45 (2008).

Knill, E. et al. An algorithmic benchmark for quantum information processing. Nature 404, 368–370 (2000).

Winograd, E. A., Rozenberg, M. J. & Chitra, R. Weak-coupling study of decoherence of a qubit in disordered magnetic environments. Phys. Rev. B 80, 214429 (2009).

Lloyd, S. Universal quantum simulators. Science 273, 1073–1078 (1996).

Leskowitz, G. & Mueller, L. State interrogation in nuclear magnetic resonance quantum-information processing. Phys. Rev. A 69, 052302 (2004).

Barenco, A. et al. Elementary gates for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 52, 3457–3467 (1995).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Chuang, I. L. et al. Bulk quantum computation with nuclear magnetic resonance: theory and experiment. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 454, 447–467 (1998).

Souza, A. M. et al. Experimental magic state distillation for fault-tolerant quantum computing. Nat. Commun. 2, 169 (2011).

Khaneja, N. et al. Optimal control of coupled spin dynamics: design of NMR pulse sequences by gradient ascent algorithms. Journal of magnetic resonance. J. Magn. Reson. 172, 296–305 (2005).

Zhang, J., Grassl, M., Zeng, B. & Laflamme, R. Experimental Implementation of a Codeword Stabilized Quantum Code preprint as arXic:1111.5445.

Negrevergne, C. et al. Benchmarking quantum control methods on a 12-qubit system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 170501 (2006).

Baugh, J. et al. Solid-state NMR three-qubit homonuclear system for quantum-information processing: control and characterization. Phys. Rev. A 73, 022305 (2006).

Mehring, M. & Mende, J. Spin-bus concept of spin quantum computing. Phys. Rev. A 73, 052303 (2006).

Maffei, P., Elbayed, K., Broundeau, J. & Canet, D. Slice selection in NMR imaging by use of the B1 gradient along the axial direction of a saddle-shaped coil. J. Magn. Reson. 95, 382–386 (1991).

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Gingras and J. D. Whitfield for insightful discussions and comments, and are grateful to the following funding sources: Croucher Foundation (M.H.Y.); DARPA under the Young Faculty Award N66001-09-1-2101-DOD35CAP, the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation, and the Sloan Foundation; Army Research Office under Contract No. W911NF- 07-1-0304 (A.A.G.); CIFAR, SHARCNET and QuantumWorks (R.L.), and NSERC (J.F.Z., R.L. and J.B.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-F.Z. and J.B. designed the NMR experiments and simulations, which were carried out by J.-F.Z.; M.-H.Y. and A.A.-G. made the theoretical proposal and contributed to the analysis of results. R.L. and J.B. supervised the experiment. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper and discussed the experimental procedures and results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S3, Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Methods (PDF 117 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Yung, MH., Laflamme, R. et al. Digital quantum simulation of the statistical mechanics of a frustrated magnet. Nat Commun 3, 880 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1860

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1860

This article is cited by

-

Noisy intermediate-scale quantum computers

Frontiers of Physics (2023)

-

Decoherence Control of Nitrogen-Vacancy Centers

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Extreme Quantum Advantage when Simulating Classical Systems with Long-Range Interaction

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

A Study on Fast Gates for Large-Scale Quantum Simulation with Trapped Ions

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Experimental realization of single-shot nonadiabatic holonomic gates in nuclear spins

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.