Abstract

Anomalous Hall effect, a manifestation of Hall effect occurring in systems without time-reversal symmetry, has been mostly observed in ferromagnetically ordered materials. However, its realization in high-mobility two-dimensional electron system remains elusive, as the incorporation of magnetic moments deteriorates the device performance compared to non-doped structure. Here we observe systematic emergence of anomalous Hall effect in various MgZnO/ZnO heterostructures that exhibit quantum Hall effect. At low temperatures, our nominally non-magnetic heterostructures display an anomalous Hall effect response similar to that of a clean ferromagnetic metal, while keeping a large anomalous Hall effect angle θAHE≈20°. Such a behaviour is consistent with Giovannini–Kondo model in which the anomalous Hall effect arises from the skew scattering of electrons by localized paramagnetic centres. Our study unveils a new aspect of many-body interactions in two-dimensional electron systems and shows how the anomalous Hall effect can emerge in a non-magnetic system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A magnetic field B applied perpendicularly to the charge carrier flow deflects the carriers upon the acting Lorentz force. In solids, this results in the carrier accumulation at the boundaries of the system until the built-up electric field EHall compensates for the transverse flow of charge carriers (Fig. 1a, left). This mechanism, so-called ordinary Hall effect, gives rise to the Hall voltage UHall being linearly proportional to B. In systems with both spin–orbit coupling and spontaneous ferromagnetic polarization, the mobile charge carriers gain an additional transverse momentum (Fig. 1b). Consequently, the built-up Hall voltage attains a component UAHE, so-called anomalous Hall component, originating from the spin–orbit interaction and being proportional to the magnetization Mz (refs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5; Fig. 1a, right). The total Hall effect, conventionally given by the Hall resistance Ryx, is then composed as:

(a) Hall voltage is built in the magnetic field B due to the Lorentz force (left panel) and due to the spin–orbit coupling in ferromagnetic material with the total magnetization M (right panel). (b) Appearance of anomalous Hall effect: electrons are deflected in the mean field of spontaneously ordered magnetic moments. (c) Anomalous Hall effect in a paramagnetic system, such as ZnO, is brought about by the spin-dependent electron scattering on localized magnetic moment J. (d) Schematic representation of anomalous Hall effect scaling behaviour found in various materials6,7.

where I is the current flowing through the system, e is the elementary charge, n is the charge carrier density, and  , where γ establishes the relation between the anomalous Hall resistance

, where γ establishes the relation between the anomalous Hall resistance  and Mz. Anomalous Hall effect (AHE) is a well-established phenomenon in intrinsically ferromagnetic metals as well as in the induced ferromagnetic degenerated semiconductors, known as diluted magnetic semiconductors (Fig. 1b). Common to both material classes is the scaling behaviour of the anomalous Hall conductivity

and Mz. Anomalous Hall effect (AHE) is a well-established phenomenon in intrinsically ferromagnetic metals as well as in the induced ferromagnetic degenerated semiconductors, known as diluted magnetic semiconductors (Fig. 1b). Common to both material classes is the scaling behaviour of the anomalous Hall conductivity  with the sample conductivity

with the sample conductivity  , where α is the scaling power factor6,7. Most materials show the power factor of either α≈1.6 or 0.0, whereas α≈1.0 is only rarely observed in the very clean ferromagnetic metals8. Such a scaling behaviour has been theoretically proposed to be reproducible in ferromagnetic systems with dilute impurities9. According to these models, α=1.6 is a characteristics of a system with a large number of scattering centres. As this number reduces α changes to 0, and in the clean limit, extrinsic scattering regime, α=1.0, is expected. Since this common scenario takes place in ferromagnets, the realization of AHE in a nominally non-magnetic system is counter-intuitive.

, where α is the scaling power factor6,7. Most materials show the power factor of either α≈1.6 or 0.0, whereas α≈1.0 is only rarely observed in the very clean ferromagnetic metals8. Such a scaling behaviour has been theoretically proposed to be reproducible in ferromagnetic systems with dilute impurities9. According to these models, α=1.6 is a characteristics of a system with a large number of scattering centres. As this number reduces α changes to 0, and in the clean limit, extrinsic scattering regime, α=1.0, is expected. Since this common scenario takes place in ferromagnets, the realization of AHE in a nominally non-magnetic system is counter-intuitive.

Here we report the observation of such an unusual effect in a high-mobility non-magnetic two-dimensional electron system formed at the interface MgZnO and ZnO, which shows both integer and fractional quantum Hall effects10,11,12. The observed AHE exhibits the scaling power factor α≅1 at low temperatures and keeps a large AHE angle θAHE≈20° (refs 7, 8, 9; Fig. 1d). Our observation is consistent with the Giovannini–Kondo (GK) model for AHE, whose mechanism sketched in Fig. 1c considers the coupling of localized magnetic moments J with the orbital momentum l of mobile electrons leading to the skew scattering amplitude J·(k × k′) (refs 13, 14, 15, 16). In particular, the model can successfully explain α≅1, linear B dependence of  at low field and

at low field and  saturation at high field. Moreover, it does not contradict to the observation of positive magnetoresistance, which is not expected in conventional cases of AHE in ferromagnets. We are not aware of another theory that can simultaneously cover all mentioned aspects of our experimental results.

saturation at high field. Moreover, it does not contradict to the observation of positive magnetoresistance, which is not expected in conventional cases of AHE in ferromagnets. We are not aware of another theory that can simultaneously cover all mentioned aspects of our experimental results.

Results

Transport characteristics of MgZnO/ZnO heterostructure

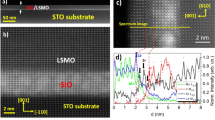

MgZnO/ZnO heterostructures studied in this work are grown with the oxide molecular beam epitaxy technique without incorporating any magnetic elements and cover a charge carrier density range between 1.7 × 1011 and 18 × 1011 cm−2 (ref. 17). Secondary ion mass spectroscopy of a typical high-mobility heterostructure confirms the absence of the undesired impurities including magnetic (Supplementary Note 1). Two-dimensional charge carriers are paramagnetic and one observes an alternating sequence of Landau levels with up and down spin orientations, as it was confirmed by the observation of multiple Landau level coincidence events12,18. At low temperatures, the samples studied in this work exhibit a conventional magnetotransport for MgZnO/ZnO heterostructures, with integer and fractional quantum Hall states as exemplified in Fig. 2a for a sample with n=1.7 × 1011 cm−2 (refs 10, 11, 12). We note that the incorporation of magnetic moments in other high-mobilty two-dimensional charge carrier systems leads frequently to the deterioration of the device performance compared to non-doped structures19,20,21,22,23. The sample shown in Fig. 2a is now discussed in detail, whereas the characteristics’ comparison of all samples follows later. At elevated temperature and high magnetic field B, the Hall resistance is linearly proportional to B and therefore one evaluates the charge carrier density n=ΔRyx/eΔB. While n decreases by three orders of magnitude between 300 and 75 K as shown in Fig. 2c, the longitudinal sample resistance Rxx displayed in Fig. 2d increases gradually in the same temperature range. This behaviour is the result of bulk charge carrier freeze-out in ZnO substrate24. Below 75 K, the interface, that is, 2D, conductance prevails, whereby it is characterized by a decreasing Rxx concomitant with a marginal change in n. In the low magnetic field region, Ryx shows the non-linear behaviour at T⩽90 K, as the lower panel of Fig. 2a illustrates it for T=10 K. Such non-linearity cannot be explained with a two-band conductance model with electron carriers in each channel (Supplementary Note 2). Therefore, the crossover from three-dimensional to 2D transport, as shown in Fig. 2c,d, cannot lead to such non-linearity. Neither the electron interaction effects can fully account for the non-linearity25,26,27 (Supplementary Note 3). Nor the electron bulk localization, which are important for the appearance of quantum Hall effect, are in play in our system28. Furthermore, the quantum Hall effect takes place only at particular values of the magnetic field and does not cover the full magnetic field range used in our experiment. Rather the non-linear Ryx is the manifestation of the AHE in ZnO. The AHE component is extracted by subtracting the ordinary Hall effect component from the raw data according to equation (1) and displayed in Fig. 2b for several temperatures. Above some field Bsat, which depends on the temperature,  remains field-independent, thus reaching the regime of saturation. This saturated AHE resistance

remains field-independent, thus reaching the regime of saturation. This saturated AHE resistance  has a non-trivial temperature dependence shown in Fig. 2e and appears in the temperature regime with a dominating 2D transport, suggesting that the AHE is associated with the 2D transport rather than with the bulk transport. The temperature dependence of

has a non-trivial temperature dependence shown in Fig. 2e and appears in the temperature regime with a dominating 2D transport, suggesting that the AHE is associated with the 2D transport rather than with the bulk transport. The temperature dependence of  follows the temperature dependence of sample resistance Rxx—both decrease with the lowering temperature (T<50 K), which is therefore consistent with the AHE scaling behaviour1,6,7,9.

follows the temperature dependence of sample resistance Rxx—both decrease with the lowering temperature (T<50 K), which is therefore consistent with the AHE scaling behaviour1,6,7,9.

(a) Magnetotransport Rxx and Ryx at two representative temperatures. (b) Anomalous Hall effect component at different temperatures. The Landau level integer filling factors ν becomes visible at T<8 K. (c) Temperature dependence of the charge carrier density extracted from the ordinary Hall effect in high field. (d) Four-point resistance Rxx as a function of temperature. (e) Temperature dependence of the saturated value of anomalous Hall effect resistance  . (f) AHE scaling:

. (f) AHE scaling:  ∝

∝ . α=0.94±0.08 is observed between 2 and 10 K, whereas α>1 at higher temperature. (g) AHE angle increases with the decreasing temperature.

. α=0.94±0.08 is observed between 2 and 10 K, whereas α>1 at higher temperature. (g) AHE angle increases with the decreasing temperature.

AHE scaling

To analyse the scalability of the anomalous Hall conductance  with the sample conductance σxx, the two parameters are conventionally calculated for each temperature6:

with the sample conductance σxx, the two parameters are conventionally calculated for each temperature6:

Figure 2f displays  versus σxx on a double logarithmic scale. Striking is the observation of scaling

versus σxx on a double logarithmic scale. Striking is the observation of scaling  ∝

∝ with α=0.94±0.08 for T⩽10 K (Supplementary Note 4). Conventionally, α=1 is associated with the skew-type electron scattering, which is understood as the asymmetric scattering for electrons with up and down spin orientations29,30. At higher temperature, α increases gradually and in a limited temperature range α=1.6 is apparent. The AHE angle tan(θAHE)=

with α=0.94±0.08 for T⩽10 K (Supplementary Note 4). Conventionally, α=1 is associated with the skew-type electron scattering, which is understood as the asymmetric scattering for electrons with up and down spin orientations29,30. At higher temperature, α increases gradually and in a limited temperature range α=1.6 is apparent. The AHE angle tan(θAHE)= /σxx, shown in Fig. 2g increases with the decreasing temperature and reaches a constant value tan(θAHE)=0.35 for T<10 K. This temperature dependence of θAHE substantiates that the AHE does not vanish at low temperatures, although one might falsely be inclined to interpret a vanishing AHE at low temperature based on temperature dependence of

/σxx, shown in Fig. 2g increases with the decreasing temperature and reaches a constant value tan(θAHE)=0.35 for T<10 K. This temperature dependence of θAHE substantiates that the AHE does not vanish at low temperatures, although one might falsely be inclined to interpret a vanishing AHE at low temperature based on temperature dependence of  displayed in Fig. 2e. As the temperature decreases below T=2 K σxx keeps increasing due to the increase of the electron mobility17. Consequently,

displayed in Fig. 2e. As the temperature decreases below T=2 K σxx keeps increasing due to the increase of the electron mobility17. Consequently,  component increases because of the scaling

component increases because of the scaling  ∝

∝ , so that its contribution to the Hall resistance Ryx at low temperature becomes more difficult to resolve. This explains why the Hall effect at 3He temperature and at the temperature of dilution refrigerator, at which the most of our previous studies have been conducted before, appears linear in the low magnetic field10,11,12. More importantly, non-vanishing AHE angle θAHE implies that the scattering mechanism leading to the AHE can sustain down to low temperature.

, so that its contribution to the Hall resistance Ryx at low temperature becomes more difficult to resolve. This explains why the Hall effect at 3He temperature and at the temperature of dilution refrigerator, at which the most of our previous studies have been conducted before, appears linear in the low magnetic field10,11,12. More importantly, non-vanishing AHE angle θAHE implies that the scattering mechanism leading to the AHE can sustain down to low temperature.

Magnetic properties

The AHE can arise in our system when the mobile electrons interact with the magnetic moments being polarized by the external magnetic field. In the absence of the external magnetic field, the AHE current is zero. However, the polarization of the localized magnetic moments by the application of the magnetic field induces the polarization of angular orbital momentum of conduction electron leading to a nonzero AHE15. The magnetic moments are likely to be the point defects in the epitaxial ZnO with localized unpaired electrons31,32,33,34 (Supplementary Note 5). Although the molecular beam epitaxy enabled to reduce the number of defects with thereof resulting high electron mobility, the defects cannot be completely avoided.

We note that, because of  =γMz(B), the character of the magnetic moments can be deduced from the analysis of the AHE field dependence displayed in Fig. 2b. It turns out that the Brillouin function, which describes the magnetization of a paramagnetic system in an external magnetic field, depicts well the field dependence of AHE for all temperatures of the experiment when assuming g=2 and J=1/2 (Supplementary Note 6). Such a description reveals that the system of localized magnetic moments is characterized by an extremely large effective magnetic moment μB shown on the left axis in Fig. 3b and is therefore qualified as a superparamagnet. The large μB reflecting the value of magnetic moment averaged over the sample, rather than the on-site value of μB, is on itself not very surprising, since both the unconventionally large values and temperature dependence of magnetic moments have also been obtained, for instance, in the studies of LaCoO3 and was explained with the formation of polarons35. Furthermore, the fact that

=γMz(B), the character of the magnetic moments can be deduced from the analysis of the AHE field dependence displayed in Fig. 2b. It turns out that the Brillouin function, which describes the magnetization of a paramagnetic system in an external magnetic field, depicts well the field dependence of AHE for all temperatures of the experiment when assuming g=2 and J=1/2 (Supplementary Note 6). Such a description reveals that the system of localized magnetic moments is characterized by an extremely large effective magnetic moment μB shown on the left axis in Fig. 3b and is therefore qualified as a superparamagnet. The large μB reflecting the value of magnetic moment averaged over the sample, rather than the on-site value of μB, is on itself not very surprising, since both the unconventionally large values and temperature dependence of magnetic moments have also been obtained, for instance, in the studies of LaCoO3 and was explained with the formation of polarons35. Furthermore, the fact that  is described with the Brillouin function, points to the polarization of localized magnetic moments, rather than the Pauli magnetization of the mobile charge carriers and serves as another confirmation for the presence of localized magnetic moments. Indeed, the consideration of the relevant energy scales, these are Fermi energy (n × 0.8 meV, where n is the charge carrier density in units 1011 cm−2), Zeeman energy (0.12 meV T−1) and the thermal energy (0.086 meV K−1), makes apparent that the electron system cannot reach the saturation of the magnetization in the magnetic fields of the experiment.

is described with the Brillouin function, points to the polarization of localized magnetic moments, rather than the Pauli magnetization of the mobile charge carriers and serves as another confirmation for the presence of localized magnetic moments. Indeed, the consideration of the relevant energy scales, these are Fermi energy (n × 0.8 meV, where n is the charge carrier density in units 1011 cm−2), Zeeman energy (0.12 meV T−1) and the thermal energy (0.086 meV K−1), makes apparent that the electron system cannot reach the saturation of the magnetization in the magnetic fields of the experiment.

(a) Temperature dependence of the anomalous Hall effect normalized to the saturated value of AHE. Such a representation makes apparent the similarity with the magnetization behaviour of a paramagnetic system. The Brillouin function describes well the field dependence of AHE. (b) Left axis: temperature dependence of μB obtained from the fitting the AHE traces in a with the Brillouin function. Right axis: temperature dependence of the slope of AHE around B=0 in a. (c) Magnetic susceptibility χ obtained from the slope of AHE and temperature dependence μB. For T<10 K, the dependence of 1/χ on T can be approximated with the Curie–Weiss law (black line).

Since μB in such a description is temperature-dependent, the relation  (B)=γ(T)Mz=γ(T)gμB(T)JBJ(g*μB(T)JB/kBT) is valid, where BJ(x) is the Brillouin function. It is now instructive to extract the temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility χ. First, we note that χ=N−1(dMz/dB)B→0=gμB(T)J

(B)=γ(T)Mz=γ(T)gμB(T)JBJ(g*μB(T)JB/kBT) is valid, where BJ(x) is the Brillouin function. It is now instructive to extract the temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility χ. First, we note that χ=N−1(dMz/dB)B→0=gμB(T)J (

( (B)/

(B)/ )B→0, where N is the number of magnetic moments. Accordingly, χ is proportional to the slope of the experimentally obtained ratio

)B→0, where N is the number of magnetic moments. Accordingly, χ is proportional to the slope of the experimentally obtained ratio  (B)/

(B)/ around zero field shown on the right axis in Fig. 3b and temperature-dependent μB.

around zero field shown on the right axis in Fig. 3b and temperature-dependent μB.

Figure 3c plots 1/χ versus T and reveals the change in the system’s magnetic magnetic properties at T=10 K. This analysis points to a striking correlation between the AHE scalability and the magnetic properties of the heterostructure, namely, the system’s magnetic property and the AHE scaling (Fig. 2f) alter at the same temperature. For T<10 K, the dependence 1/χ versus T can be approximated with the Curie–Weiss law with the Curie–Weiss temperature Tcw approaching 0 K.

Comparison of studied MgZnO/ZnO heterostructures

All MgZnO/ZnO heterostructures covering a range of charge carrier density between 1.7 × 1011 and 18 × 1011 cm−2 feature qualitatively same characteristics. Figure 4a shows the scaling of  with σxx, while Fig. 4b plots 1/χ versus T for all samples. The rigorous analysis of AHE conductance scaling at low temperature shows that the scaling power factor α lies between 0.92 and 1.08, whereas the error bar covers α=1.0 (Supplementary Note 7). Thus, all structures show both the AHE scaling power α=1 and the change in the system’s magnetic property at low temperature. All data in Fig. 4a fall in one straight line when plotted on the same scale (Supplementary Note 7). It is striking that above some critical temperature, which depends on n and is indicated by filled symbol for samples A–D, α increases with the increasing temperature and simultaneously the magnetic characteristic changes, that is, the dependence 1/χ on T peaks at the critical temperature and thereafter 1/χ falls with T. Although such a correlation is particularly well pronounced in low carrier density samples, it is quite apparent that the magnetic properties are reflected in the Hall transport characteristics. Furthermore, a non-vanishing Hall angle displayed in Fig. 4c implies a persistent interaction of mobile electrons with the localized magnetic moments at all temperatures.

with σxx, while Fig. 4b plots 1/χ versus T for all samples. The rigorous analysis of AHE conductance scaling at low temperature shows that the scaling power factor α lies between 0.92 and 1.08, whereas the error bar covers α=1.0 (Supplementary Note 7). Thus, all structures show both the AHE scaling power α=1 and the change in the system’s magnetic property at low temperature. All data in Fig. 4a fall in one straight line when plotted on the same scale (Supplementary Note 7). It is striking that above some critical temperature, which depends on n and is indicated by filled symbol for samples A–D, α increases with the increasing temperature and simultaneously the magnetic characteristic changes, that is, the dependence 1/χ on T peaks at the critical temperature and thereafter 1/χ falls with T. Although such a correlation is particularly well pronounced in low carrier density samples, it is quite apparent that the magnetic properties are reflected in the Hall transport characteristics. Furthermore, a non-vanishing Hall angle displayed in Fig. 4c implies a persistent interaction of mobile electrons with the localized magnetic moments at all temperatures.

(a) Scaling of anomalous Hall effect  ∝

∝ with α=1 (blue solid line) at low temperature is observed for structures covering a wide range of charge carrier density. For clarity of representation,

with α=1 (blue solid line) at low temperature is observed for structures covering a wide range of charge carrier density. For clarity of representation,  for each sample is multiplied by a factor shown in the box. α increases at elevated temperature. (b) The inverse spin-susceptibility 1/χ peaks at some temperature indicated by solid symbol (except the highest density sample) and suggests the change in the system’s magnetic property. This transition temperature is higher for higher carrier density samples and correlates with the temperature at which α starts deviating from 1, except the samples E–G with the higher carrier concentration. At low temperature, 1/χ versus T dependence can be approximated with the Curie–Weiss law with a characteristic temperature Tcw. (c) Temperature dependence of AHE angle for all samples. The AHE angle lies in the range between tan(θAHE)=0.3 and tan(θAHE)=0.5 at T=2 K, indicating a non-vanishing AHE at low temperature. (d) Tcw increases with the increasing carrier density. Error bar is given by the uncertainty with which the linear dependence 1/χ versus T can be approximated in b.

for each sample is multiplied by a factor shown in the box. α increases at elevated temperature. (b) The inverse spin-susceptibility 1/χ peaks at some temperature indicated by solid symbol (except the highest density sample) and suggests the change in the system’s magnetic property. This transition temperature is higher for higher carrier density samples and correlates with the temperature at which α starts deviating from 1, except the samples E–G with the higher carrier concentration. At low temperature, 1/χ versus T dependence can be approximated with the Curie–Weiss law with a characteristic temperature Tcw. (c) Temperature dependence of AHE angle for all samples. The AHE angle lies in the range between tan(θAHE)=0.3 and tan(θAHE)=0.5 at T=2 K, indicating a non-vanishing AHE at low temperature. (d) Tcw increases with the increasing carrier density. Error bar is given by the uncertainty with which the linear dependence 1/χ versus T can be approximated in b.

Finally, at low temperature, 1/χ dependence on T can be approximated with the Curie–Weiss law (except the highest carrier density sample) and we obtain Tcw at which the divergence of the uniform susceptibility is expected. Figure 4d shows the increase of the absolute value of Tcw with the carrier density, which may imply the importance of the electron correlation for the AHE appearance.

Discussion

Our experimental results are compatible with the theoretical framework developed by GK13,15. At the moment, there is no any other theoretical model, where  (B) is given by the Brillouin function to describe the polarization of localized magnetic moments by the external magnetic field. Also, GK model can explain the experimentally observed scaling between

(B) is given by the Brillouin function to describe the polarization of localized magnetic moments by the external magnetic field. Also, GK model can explain the experimentally observed scaling between  and σxx, which is different from the scaling behaviour predicted by other AHE models. As mentioned above, the crucial ingredient of GK model is the coupling between the total angular momentum of localized magnetic moments J and the orbital motion l of mobile electrons, which leads to AHE as the result of the skew scattering. In such a system, the essential transport properties are characterized by (i) the total relaxation rate τ−1=τ−1(B, T) accounting for the scattering in magnetic as well as non-magnetic channels, for example, phonons and so on, and (ii) the transport correction to the cyclotron frequency ξAHE(B, T) originating exclusively from the skew scattering. Then the Hall angle is given by (Supplementary Note 8):

and σxx, which is different from the scaling behaviour predicted by other AHE models. As mentioned above, the crucial ingredient of GK model is the coupling between the total angular momentum of localized magnetic moments J and the orbital motion l of mobile electrons, which leads to AHE as the result of the skew scattering. In such a system, the essential transport properties are characterized by (i) the total relaxation rate τ−1=τ−1(B, T) accounting for the scattering in magnetic as well as non-magnetic channels, for example, phonons and so on, and (ii) the transport correction to the cyclotron frequency ξAHE(B, T) originating exclusively from the skew scattering. Then the Hall angle is given by (Supplementary Note 8):

According to Fig. 4c, the AHE angle converges towards tan θAHE≈0.4 for all samples and shows a weak temperature dependence at low temperature. In accordance with equation (4), this fact implies  (B=0, T)≈

(B=0, T)≈ (Bsat, T), which therefore reproduces the scaling relation

(Bsat, T), which therefore reproduces the scaling relation  with α=1 identified in Figs 2f and 4a. However, when the temperature is high enough the relaxation rate

with α=1 identified in Figs 2f and 4a. However, when the temperature is high enough the relaxation rate  , including the phonon scattering, dominates over the scattering in magnetic channel, that is,

, including the phonon scattering, dominates over the scattering in magnetic channel, that is,  , which results in a decreasing θAHE with increasing T seen in Fig. 4c.

, which results in a decreasing θAHE with increasing T seen in Fig. 4c.

The surprising appearance of the AHE in non-magnetic ZnO-based 2D electron system shows a new facet of many-body correlation phenomena in low-dimensional systems, which may lead to the unprecedented quantum phenomena. Moreover, the suggested Giovannini-Kondo model being compatible with the observations in ZnO can also be anticipated in other material systems36,37. Thus, ZnO lends itself as a test bed to explore the effects of localized impurities and phonon scattering on the AHE appearance in low disorder 2D electron systems.

Methods

Sample summary

Table 1 describes the MgZnO/ZnO heterostructures that are used in the current work.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Maryenko, D. et al. Observation of anomalous Hall effect in a non-magnetic two-dimensional electron system. Nat. Commun. 8, 14777 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14777 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Nagaosa, N., Sinova, J., Onoda, S., MacDonald, A. H. & Ong, N. P. Anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1539–1592 (2010).

Oveshnikov, L. N. et al. Berry phase mechanism of the anomalous Hall effect in a disordered two-dimensional magnetic semiconductor structure. Sci. Rep. 5, 17158 (2015).

Chang, C.-Z. et al. Experimental observation of the quantum anomalous Hall effect in a magnetic topological insulator. Science 340, 167–170 (2013).

Liu, X.-J., Liu, X. & Sinova, J. Scaling of the anomalous Hall effect in the insulating regime. Phys. Rev. B 84, 165304 (2011).

Glushkov, V. V. et al. Scrutinizing Hall effect in Mn1−xFexSi: Fermi surface evolution and hidden quantum criticality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 256601 (2015).

Fukumura, T. et al. A scaling relation of anomalous Hall effect in ferromagnetic semiconductors and metals. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 46, L642–L644 (2007).

Onoda, S., Sugimoto, N. & Nagaosa, N. Quantum transport theory of anomalous electric, thermoelectric, and thermal Hall effects in ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 77, 165103 (2008).

Miyasato, T. et al. Crossover behavior of the anomalous Hall effect and anomalous Nernst effect in itinerant ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 086602 (2007).

Onoda, S., Sugimoto, N. & Nagaosa, N. Intrinsic versus extrinsic anomalous Hall effect in ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 126602 (2006).

Tsukazaki, A. et al. Observation of the fractional quantum Hall effect in an oxide. Nat. Mater. 9, 889–893 (2010).

Maryenko, D. et al. Temperature-dependent magnetotransport around ν=1/2 in ZnO heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 186803 (2012).

Falson, J. et al. Even-denominator fractional quantum Hall physics in ZnO. Nat. Phys. 11, 347–351 (2015).

Kondo, J. Anomalous Hall effect and magnetoresistance of ferromagnetic metals. Prog. Theor. Phys. 27, 772–792 (1962).

Fert, A. & Jaoul, O. Left-right asymmetry in the scattering of electrons by magnetic impurities, and a Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 28, 303–307 (1972).

Giovannini, B. Skew scattering in dilute alloys. I. The Kondo model. J. Low Temp. Phys. 11, 489–507 (1973).

Fert, A. & Friederich, A. Skew scattering by rare-earth impurities in silver, gold, and aluminum. Phys. Rev. B 13, 397–411 (1976).

Falson, J., Maryenko, D., Kozuka, Y., Tsukazaki, A. & Kawasaki, M. Magnesium doping controlled density and mobility of two-dimensional electron gas in MgxZn1−xO/ZnO heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Express 4, 091101 (2011).

Maryenko, D., Falson, J., Kozuka, Y., Tsukazaki, A. & Kawasaki, M. Polarization-dependent Landau level crossing in a two-dimensional electron system in a MgZnO/ZnO heterostructure. Phys. Rev. B 90, 245303 (2014).

Smorchkova, I. P., Samarth, N., Kikkawa, J. M. & Awschalom, D. D. Spin transport and localization in a magnetic two-dimensional electron gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 3571–3574 (1997).

Cumings, J. et al. Tunable anomalous Hall effect in a nonferromagnetic system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 196404 (2006).

Betthausen, C. et al. Fractional quantum Hall effect in a dilute magnetic semiconductor. Phys. Rev. B 90, 115302 (2014).

Oveshnikov, L. N., Kul’bachinskii, V. A., Davydov, A. B. & Aronzon, B. A. Anomalous Hall effect in a 2D heterostructure including a GaAs/InGaAs/GaAs quantum well with a remote Mn δ-layer. JETP Lett. 100, 570–575 (2014).

Kunc, J. et al. Magnetoresistance quantum oscillations in a magnetic two-dimensional electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 92, 085304 (2015).

Tsukazaki, A. et al. High electron mobility exceeding 104 cm−2V−1s−1 in MgxZn1−xO/ZnO single heterostructures grown by molecular beam epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Express 1, 055004 (2008).

Lee, P. A. & Ramakrishnan, T. V. Disordered electronic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 57, 287–337 (1985).

Lee, P. A. & Ramakrishnan, T. V. Magnetoresistance of weakly disordered electrons. Phys. Rev. B 26, 4009–4012 (1982).

Altshuler, B. L. & Aronov, A. G. Electron-Electron Interaction in Disordered Systems North-Holland (1985).

Beugeling, W., Liu, C. X., Novik, E. G., Molenkamp, L. W. & Morais Smith, C. Reentrant topological phases in Mn-doped HgTe quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 85, 195304 (2012).

Smit, J. The spontaneous Hall effect in ferromagnetics I. Physics 21, 877–887 (1955).

Chazalviel, J. N. & Solomon, I. Experimental evidence of the anomalous Hall effect in a nonmagnetic semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 29, 1676–1679 (1972).

Xu, Q. et al. Room temperature ferromagnetism in ZnO films due to defects. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 082508 (2008).

Oba, F., Choi, M., Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. Point defects in ZnO: an approach from first principles. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 12, 034302 (2011).

Chakrabarty, A. & Patterson, C. H. Defect-trapped electrons and ferromagnetic exchange in ZnO. Phys. Rev. B 84, 054441 (2011).

Erhart, P., Albe, K. & Klein, A. First-principles study of intrinsic point defects in ZnO: Role of band structure, volume relaxation, and finite-size effects. Phys. Rev. B 73, 205203 (2006).

Yamaguchi, S., Okimoto, Y., Taniguchi, H. & Tokura, Y. Spin-state transition and high-spin polarons in LaCoO3 . Phys. Rev. B 53, R2926–R2929 (1996).

Toyosaki, H. et al. Anomalous Hall effect governed by electron doping in a room-temperature transparent ferromagnetic semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 3, 221–224 (2004).

Shimizu, S. et al. Electrically tunable anomalous Hall effect in Pt thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 216803 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Nakamura, J. Matsuno, K. Takahashi, T. Dietl, D. Goldhaber-Gordon and L.W. Molenkamp for fruitful discussions. This work was partly supported by Grant-in-Aids for Scientific Research (S) nos 24226002 and 24224009 from MEXT, Japan, ‘Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R&D on Science and Technology (FIRST)’ Program from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) initiated by the Council for Science and Technology Policy as well as by the ImPACT Program of the Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (Cabinet Office, Government of Japan). A.E. is grateful for financial support by DFG in the framework of SFB762 Functionality of Oxide Interfaces.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M. conceived the research project, carried out the experiments and analysed the data. J.F. grew samples. D.M., A.S.M., M.S.B. and M.K. discussed the results. A.S.M., M.S.B., A.E. and N.N. worked out the theory. D.M. wrote the manuscript with contribution from A.S.M., M.S.B. and A.E. M.K. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the discussion and commented on the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Notes and Supplementary References (PDF 1357 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Maryenko, D., Mishchenko, A., Bahramy, M. et al. Observation of anomalous Hall effect in a non-magnetic two-dimensional electron system. Nat Commun 8, 14777 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14777

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14777

This article is cited by

-

Oxygen Vacancy-Induced Anomalous Hall Effect in a Nominally Non-magnetic Oxide

Journal of Electronic Materials (2022)

-

Gate-tuned anomalous Hall effect driven by Rashba splitting in intermixed LaAlO3/GdTiO3/SrTiO3

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.