Abstract

Graded expression of EphB and ephrin-B along the dorsoventral axis of the retina indicates a role for these bidirectional signalling molecules in dorsoventral–mediolateral retinocollicular mapping. Although previous studies have implicated EphB2 forward signalling in mice, the intracellular component of EphB2 essential for retinocollicular mapping is unknown as are the roles for EphB1, ephrin-B1, and ephrin-B2. Here we show that EphB2 tyrosine kinase catalytic activity and EphB1 intracellular signalling are key mediators of ventral–temporal retinal ganglion cell axon retinocollicular mapping, by likely interacting with ephrin-B1 in the superior colliculus. We further elucidate roles for the ephrin-B2 intracellular domain in retinocollicular mapping and present the unexpected finding that both dorsal and ventral–temporal retinal ganglion cell axons utilize reverse signalling for topographic mapping. These data demonstrate that both forward and reverse signalling initiated by EphB:ephrin-B interactions have a major role in dorsoventral retinal ganglion cell axon termination along the mediolateral axis of the superior colliculus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), distributed along the dorsoventral axis of the retina, extend axons that terminate along the mediolateral axis of the superior colliculus (SC), whereas those distributed along the nasotemporal axis of the retina terminate along the rostrocaudal axis1,2. As they project along the SC rostrocaudal axis, RGC axons extend interstitial branches along the mediolateral axis that orient themselves towards their future termination zone (TZ) utilizing both repulsive and attractive mechanisms2. Ryk:Wnt3 signalling likely mediates the repulsion underlying mediolateral interstitial branch direction3, whereas the B-subclass Eph/ephrin molecules are thought to serve as an attractive counterbalance to these signals4. Ventral–temporal (VT) RGC axons of EphB2−/−;EphB3−/− and EphB2lacZ/lacZ;EphB3−/− compound mutants exhibited misprojecting interstitial branches that formed lateral biased ectopic TZs (eTZs) in the SC demonstrating a role for EphB:ephrin-B forward signalling in retinocollicular mapping. However, many questions remain about the individual contribution of EphB2 and EphB3 and a potential role for the related EphB1 receptor. Despite its robust VT retinal expression and key role in mediating axonal repulsion at the optic chiasm to form the ipsilateral projections essential for binocular vision5, nothing is known regarding how EphB1 participates in retinocollicular mapping. Likewise, despite the high dorsal/low ventral gradient of ephrin-B2 in the retina and elevated midline expression of ephrin-B1 in the SC4, the functions of these two molecules in mice are unknown.

Using a diverse array of targeted mutations, we report here that EphB1 and EphB2 are the chief guidance molecules that mediate VT RGC axon targeting to the medial-rostral SC and that EphB2 tyrosine kinase catalytic activity is necessary. Genetic studies further demonstrated that ephrin-B1 is the primary ligand expressed in the SC for the mapping of VT RGC axons expressing EphB receptors. Finally, we show that reverse signalling mediated by high dorsal/low ventral expressed ephrin-B2 is important for retinocollicular mapping throughout the dorsoventral axis of the retina. Our study thus establishes the essential roles for both EphB1/EphB2 forward signalling and ephrin-B2 reverse signalling in guiding RGC axons to their proper TZ in the SC.

Results

EphB and ephrin-B expression in the retina and SC

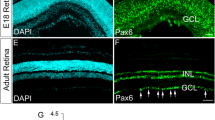

EphB2 expression in coronal sections of the retina and SC was confirmed using X-gal stains of EphB2lacZ mutants, which express a carboxy-terminal truncated EphB2–β-gal fusion protein lacking the majority of the EphB2 intracellular domain including its tyrosine kinase catalytic domain, sterile alpha motif domain, and PSD95/Dlg/ZO1 (PDZ) binding motif6. This protein correctly traffics to the cell membrane and can act like a ligand to bind ephrin-B on adjacent cell surfaces to activate reverse signalling, but cannot transduce canonical forward signals into its own cell requiring the removed internal sequences. EphB2–β-gal expression visualized using X-gal staining matches both EphB2 expression visualized using anti-EphB2 antibody and EphB2 messenger RNA expression, as shown in embryonic and postnatal retinas, respectively4,6. The EphB2–β-gal fusion protein illustrates endogenous EphB2 protein expression in a high ventral/low dorsal gradient in the RGC layer at embryonic day 17.5 (E17.5) and postnatal days 1 (P1) and 8 (P8), although there is obvious expression in the dorsal retina (Fig. 1a). The localization of EphB2–β-gal at these stages is highly enriched in the RGC axons funneling into the optic nerve head (arrowheads in Fig. 1a), as previously documented with EphB2 antibodies to detect the endogenous wild type (WT) protein6. In the brain, expression of EphB2 is also strong in the superficial and deeper layers of the SC at P1 and P8, but not in any visible gradient (Fig. 1a).

(a) EphB2lacZ mutants express a C-terminal, intracellular truncated EphB2–β-gal fusion protein that reaches the cell membrane and traffics to its normal cellular locations. X-gal stains of coronal sections from an E17.5 embryo, and P1 and P8 pups show EphB2 is expressed in a high ventral/low dorsal gradient in the retina and is localized to RGC axons that funnel into the optic nerve (arrowheads). EphB2–β-gal fusion protein is expressed uniformly in the SC at P1 and P8. (b) EphB1T-lacZ mutants express a C-terminal, intracellular truncated EphB1–β-gal fusion protein that reaches the cell membrane and traffics to its normal cellular locations. X-gal stains of coronal sections from an E16.5 embryo, and P1 and P8 pups show EphB1 is highly expressed in the VT region of the embryonic retina, becoming more uniformly distributed at postnatal stages, and is localized to RGC axons that funnel into the optic nerve (arrowheads). EphB1lacZ mutants express unconjugated β-gal in the cell body, and X-gal stains here show strong uniform expression within cells of the SC. (c) Ephrin-B2lacZ mutants express a C-terminal, intracellular truncated ephrin-B2–β-gal fusion protein that reaches the cell membrane and traffics to its normal cellular locations. X-gal stains of coronal sections from an E17.5 embryo, and P0 and P8 pups show ephrin-B2 is expressed in a high dorsal/low ventral gradient in the retina and is localized to RGC axons that funnel into the optic nerve (arrowheads). Scale bar, 100 μm. D, dorsal; V, ventral; M, medial; L, Lateral.

To determine EphB1 expression in the retina and SC, two different EphB1 knock-in reporter lines expressing β-gal were used. In EphB1lacZ mutants5, homologous recombination was used to insert a sa-IRES-lacZ cassette into EphB1 reading frame at exon 3 resulting in a protein-null mutation that also expresses a cytoplasmic β-gal reporter in cells that normally express EphB1. In EphB1T-lacZ mutants7, lacZ sequences were inserted in-frame into exon 9, directly after the transmembrane sequences, truncating the entire intracellular domain of the protein to express an EphB1–β-gal fusion protein. Similar to the EphB2–β-gal fusion protein, the EphB1–β-gal fusion also traffics normally to the cell membrane. X-gal stains for the EphB1T-lacZ mutant reporter faithfully documented robust VT expression of EphB1 in the RGC layer at E16.5 whereas the dorsal and ventral-nasal retina expressed EphB1 at lower levels (Fig. 1b). EphB1 mRNA expression data at various embryonic stages also validates the X-gal patterns observed here5. By the first postnatal week, EphB1 expression loses its gradient and becomes expressed uniformly as shown at P1 and P8 using the EphB1T-lacZ allele (Fig. 1b). EphB1–β-gal fusion protein was expressed in the RGC axons exiting into the optic nerve (arrowheads in Fig. 1b). The EphB1lacZ mutant reporter was used to assess EphB1 expression in the SC as the expression of unconjugated β-gal labels primarily cell bodies of expressing cells and not their processes. Here again, like EphB2, strong EphB1 expression was detected in the cells of the superficial and deeper layers of the SC at P1 and P8, and did not form a detectable gradient (Fig. 1b).

Ephrin-B2 expression was determined using ephrin-B2lacZ mutant mice, which express a C-terminal truncated ephrin-B2–β-gal fusion protein that lacks the intracellular segment8. The ephrin-B2–β-gal fusion protein is able to traffic to the cell membrane and bind Eph receptors on adjacent cells to activate forward signalling, but it is unable to transduce reverse signals into its own cell. X-gal stains of ephrin-B2lacZ mice revealed a robust high dorsal/low ventral gradient expression of ephrin-B2–β-gal fusion protein in the RGC layer at E17.5, P0, and P8 (Fig. 1c), which complements previous mRNA expression data4,9. While the ephrin-B2–β-gal fusion protein was observed to be most intense in the dorsal retina, ventral expression was also evident at E17.5 and this became more obvious during the first postnatal week as seen at P0 and P8. The ephrin-B2–β-gal fusion protein is also particularly evident in axons leaving the dorsal retina as they form the optic nerve (arrowheads in Fig. 1c).

EphB2 forward signalling alone is needed for VT axon mapping

Hindges et al.4 previously reported significant retinocollicular mapping errors in EphB2−/−;EphB3−/− and EphB2lacZ/lacZ;EphB3−/− compound mutants, but did not analyse EphB2 single mutants to determine the contribution of this receptor separately from EphB3. Therefore, DiI was focally injected into the dorsal or VT retina to anterograde label RGCs so that formation of their TZs could be analysed at P8 (Fig. 2a). Also shown is an example of how a focal injection into the dorsal retina labels a TZ in the lateral SC of a WT mouse. Likewise, a focal injection into the VT retina illustrates the typical TZ size and medial-rostral location in a WT mouse, accompanied by the retinal flatmount to document the injection site (Fig. 2b). Of a total of 109 WT mice injected in the VT retina in our study, only 3 (<3%) formed an eTZ and of a total of 87 WT mice injected into the dorsal retina, only 1 (1%) of the SC formed an eTZ. In our analysis, the SC for each specimen that formed one or more eTZ had its primary and secondary TZs outlined, and then these images were superimposed according to genotype with the primary TZ positioned at the crosshairs of the compass as observed for the three WT ventral injected retinas that showed termination errors (Fig. 2b). The schematic summary allows for the qualitative assessment of the localization of the eTZs relative to the primary TZ.

(a) Top, schematic of the site of DiI injection in the dorsal or VT eye labelling RGCs and the expected TZ for their axonal projections in the lateral or medial contralateral SC, respectively. Bottom, dorsal view of a midbrain whole-mount depicting a normal TZ in the lateral SC from a WT mouse injected with DiI in the dorsal retina as verified in the flatmount (insert) and viewed using epifluorescence microscopy. (b) Top, example of a retina flatmount (insert) and SC whole mount from a WT mouse injected with DiI in the VT retina. Of 109 injected WT specimens analysed, only 3 formed one or more eTZs (3%). Bottom, the SC for each specimen that formed at least one eTZ had their eTZs and corresponding primary TZ outlined in the same colour. All outlines of the same genotype, in this case WT, were then superimposed on each other with the primary TZ positioned at the crosshairs of the compass as illustrated. (c) VT injected EphB2lacZ/+ heterozygotes formed eTZs (arrows) in 7/22 SC analysed. (d) VT injected EphB2lacZ/lacZ homozygotes formed eTZs (arrows) in 8/13 SC analysed. (e) Graphic summary of the percent of SC that formed eTZs in mice injected with DiI in the dorsal or VT retina. Dorsal injected: WT (1%, n=87), EphB2+/− (15%, P=0.0437, n=13), EphB2−/− (0%, n=3), EphB2lacZ/+ (0%, n=35), and EphB2lacZ/lacZ (0%, n=25). VT injected: WT (3%, n=109), EphB2+/− (6%, n=16), EphB2−/− (21%, P=0.0194, n=14), EphB2lacZ/+ (32%, P=0.0001, n=22), and EphB2lacZ/lacZ (62%, P<0.0001, n=13). FET compared mutant groups with WT mice. Statistical significance is denoted by asterisks: *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01, and ***P≤0.001. Scale bar, 500 μm. C, caudal; L, lateral; M, medial; R, rostral.

EphB2−/− protein-null single mutants and EphB2lacZ/lacZ C-terminal truncation mutants6 were used to determine the involvement of EphB2 and the contribution of its intracellular domain, respectively. Only 21% (P=0.0194, Fisher's exact test [FET], n=14) of VT injected EphB2−/− homozygotes and 6% (n=16) of the EphB2+/− heterozygotes formed 1-3 eTZs. In contrast, 62% (P<0.0001, FET, n=13) of the EphB2lacZ/lacZ homozygotes formed 1–4 eTZs and even 32% (P=0.0049, FET, n=22) of the EphB2lacZ/+ heterozygotes formed 1–3 eTZs (Fig. 2c–e). Whereas many eTZs were lateral to the primary TZ, RGC axons also terminated caudal relative to the primary TZ in several cases. The increased frequency of mapping errors in the EphB2lacZ mice indicates a dominant-negative effect due to expression of the C-terminal truncated EphB2–β-gal fusion protein as seen in other studies4,8,10. Together, these data show that disruption of EphB2 forward signalling hinders the formation of a properly localized, single TZ in axons from the VT retina.

EphB2 mutant SC that received focal injections of DiI into the dorsal retina did not significantly form any eTZs. Neither the EphB2lacZ/+ (n=35) or EphB2lacZ/lacZ (n=25) forward signalling mutants formed any eTZ and only 15% (n=13) of the EphB2+/− and 0% of the EphB2−/− (n=3) formed an eTZ (Fig. 2e), indicating EphB2 participates mainly in retinocollicular mapping of ventral RGC axons.

EphB2 kinase activity is essential for VT axon mapping

The data above using the EphB2lacZ allele indicated a critical role for EphB2 forward signalling in retinocollicular mapping; however, it does not identify the specific intracellular signalling component responsible. Therefore, a variety of point mutations were analysed that disrupt either tyrosine kinase catalytic activity (EphB2K661R), the ability to bind PDZ domain-containing proteins (EphB2ΔVEV), or both catalytic activity and PDZ binding (EphB2K661RΔVEV)11. VT RGC axons in 50% (P<0.0001, FET, n=10) of the EphB2K661R/K661R homozygotes and 21% (P=0.0194, FET, n=14) of the EphB2K661R/+ heterozygotes formed 1–2 eTZs lateral to the primary TZ (Fig. 3a,b). The penetrance of eTZs in the EphB2K661R mutants was not significantly different from corresponding EphB2lacZ mutants indicating the tyrosine kinase catalytic activity is the key component for EphB2 intracellular signalling required for VT axon retinocollicular mapping.

(a) Example of retinal flatmounts (inserts), SC whole mounts, and summary schematics of eTZs in WT specimens injected with DiI in the VT or dorsal retina. (b) VT injected EphB2K661R/K661R homozygotes formed eTZs (arrows) in 5/10 SC analysed. Graphic summary of the percent of SC that formed eTZs in mice injected in the VT retina: WT (3%, n=109), EphB2K661R/+ (21%, P=0.0194, n=14), and EphB2K661R/K661R (50%, P<0.0001, n=10). (c) VT injected EphB2F620D/+ heterozygotes formed eTZs (arrows) in 3/19 SC analysed and those injected in the dorsal retina formed eTZs in 4/26 SC. (d) VT injected EphB2F620D/F620D homozygotes formed eTZs (arrows) in 5/17 SC analysed and those injected in the dorsal retina formed eTZs in 2/22 SC. Graphic summary of the percent of SC that formed eTZs in mice injected in the dorsal or VT retina. Dorsal injected: WT (1%, n=87), EphB2F620D/+ (15%, P=0.0257, n=26), and EphB2F620D/F620D (9%, n=22). VT injected: WT (3%, n=109), EphB2F620D/+ (16%, P=0.042, n=19), and EphB2F620D/F620D (29%, P=0.0011, n=17). (e) Schematic of eTZs from EphB3−/− single mutants and EphB2ΔVEV/ΔVEV;EphB3−/− and EphB2K661RΔVEV/K661RΔVEV;EphB3−/− compound mutants injected with DiI into the VT retina. VT injected EphB3−/− homozygotes formed eTZs in 9/48 SC, EphB2ΔVEV/ΔVEV;EphB3−/− compound mutants formed eTZ in 3/12 SC, and EphB2K661RΔVEV/K661RΔVEV;EphB3−/− compound mutants formed eTZ in 8/19 SC. Graphic summary of the percent of SC that formed eTZs in mice injected with DiI into the VT retina: WT (3%, n=109), EphB3−/− (19%, P=0.0013, n=48), EphB2+/−;EphB3−/− (23%, P=0.0001, n=48), EphB2−/−;EphB3−/− (36%, P=0.0012, n=11), EphB2ΔVEV/+;EphB3−/− (26%, P=0.0009, n=23), EphB2ΔVEV/ΔVEV;EphB3−/− (25%, P=0.0128, n=12), EphB2K661RΔVEV/+;EphB3−/− (33%, P<0.0001, n=24), and EphB2K661RΔVEV/K661RΔVEV;EphB3−/− (42%, P<0.0001, n=19). FET compared mutant groups to WT mice. Statistical significance is denoted by asterisks: *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01, and ***P≤0.001. Scale bar, 500 μm. C, caudal; L, lateral; M, medial; R, rostral.

The involvement of EphB2 tyrosine kinase activity was also examined using kinase overactive EphB2F620D mutants that contains a point mutation in the catalytic domain rendering EphB2 constitutively active, independent of ligand binding12. While 16% (P=0.042, FET, n=19) of VT injected EphB2F620D/+ heterozygotes formed 1–3 lateral eTZs, 29% (P=0.0011, FET, n=17) of the corresponding EphB2F620D/F620D homozygotes formed 1–2 lateral or caudal eTZs (Fig. 3c,d). Of the specimens injected with DiI into the dorsal retina, 15% (P=0.0257, FET, n=26) of the EphB2F620D/+ heterozygotes and 9% (n=22) of EphB2F620D/F620D homozygotes formed 1–2 eTZs medial to the primary TZ (Fig. 3c,d). Combined, these data suggest that both ventral and dorsal RGC axons are somewhat affected by an overactive EphB2 catalytic domain, which is consistent with the robust ventral EphB2 expression and low, although detectable, level of EphB2 expression in the dorsal retina.

The contribution of the EphB2 PDZ binding motif to retinocollicular mapping of VT axons was also examined in EphB2ΔVEV/ΔVEV mutants in the background of the EphB3−/− protein-null mutant and was found not to participate in TZ formation, whereas the corresponding EphB2K661RΔVEV/K661RΔVEV; EphB3−/− compound mutants showed no extra defects over what was found for the EphB2K661R/K661R kinase-dead single mutants (Fig. 3e).

EphB1 forward signalling is also utilized for VT axon mapping

Previous studies have not looked at potential roles of the EphB1 receptor tyrosine kinase in retinocollicular mapping, even though it is expressed in the visual system (Fig. 1b) and has been documented to mediate the repulsion of VT RGC axons at the optic chiasm to form ipsilateral projections5. Therefore, VT and dorsal RGC axons were labelled with DiI in EphB1−/− protein-null mutants. Whereas dorsal RGC axons terminated normally to a well-defined TZ, the VT axons in EphB1−/− homozygotes exhibited a highly penetrant mapping defect in which 65% (P<0.0001, FET, n=20) of the SC showed 1–3 eTZs (Fig. 4a,b). Even 38% (P=0.0003, FET, n=13) of the VT-labelled EphB1+/− heterozygotes formed 1–3 eTZs, indicating a strong dosage effect. These eTZs tended to form lateral relative to the primary TZ. Additionally, it was often noted that the primary TZ in the mutants was not compact like that observed in WT, and, in one case, a distinct primary TZ was not visible.

(a) Example of retinal flatmount (insert), SC whole mount, and summary schematic of eTZs in WT specimens injected with DiI in the VT retina. (b) VT injected EphB1−/− homozygotes formed eTZs (arrows) in 13/20 SC analysed. (c) VT injected EphB1T-lacZ/T-lacZ homozygotes formed eTZs (arrows) in 10/17 SC analysed. (d) Graphic summary of the percent of SC that formed eTZs in mice injected in the dorsal or VT retina. Dorsal injected: WT (1%, n=87), EphB1+/− (0%, n=15), and EphB1−/− (0%, n=13). VT injected: WT (3%, n=109), EphB1+/− (38%, P=0.0003, n=13), EphB1−/− (65%, P<0.0001, n=20), EphB1T-lacZ/+ (20%, n=5), and EphB1T-lacZ/T-lacZ (59%, P<0.0001, n=17). ND, not done. FET compared mutant groups with WT mice. Statistical significance is denoted by asterisks: *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01, and ***P≤0.001. Scale bar, 500 μm. C, caudal; L, lateral; M, medial; R, rostral.

To determine whether forward signalling mediated by the EphB1 intracellular domain is important, EphB1T-lacZ mutant mice expressing the C-terminal truncated EphB1–β-gal fusion protein described above were analysed. The data showed that 59% (P<0.0001, FET, n=17) of the EphB1T-lacZ/T-lacZ homozygotes and 20% (P=ns, FET, n=5) of the EphB1T-lacZ/+ heterozygotes formed 1–3 eTZs usually lateral to the primary TZ following DiI injection into the VT retina (Fig. 4c,d). Like EphB2, these results indicate that forward signalling mediated by the EphB1 intracellular domain is required for retinocollicular mapping of VT RGC axons.

Synergistic role for EphB1 and EphB2 in VT axon mapping

To determine whether EphB1 and EphB2 work together to mediate retinocollicular mapping, DiI was used to trace RGC axons in EphB1;EphB2 compound mutants. The EphB1− protein-null allele was combined with either EphB2− protein-null, eliminating both forward and reverse signalling, or the EphB2lacZ allele, eliminating only EphB2 forward signalling. Following labelling of VT RGC axons, 100% of the EphB1−/−;EphB2+/− (P<0.0001, FET, n=12,) and EphB1−/−;EphB2−/− (P<0.0001, FET, n=7) SC analysed exhibited 1–5 eTZs that localized caudal, lateral, and lateral–caudal relative to the primary TZ (Fig. 5a,b). These mutants also exhibited an increase in stray axonal projections, and the primary TZ was often not fully compact, appearing diffused, compared with WT. The complete 100% penetrance and severity of the mapping defect indicates these molecules work synergistically to control the targeting of VT RGC axons within the SC.

(a) VT injected EphB1−/−;EphB2+/− compound mutants formed eTZs (arrows) in 12/12 SC analysed. (b) VT injected EphB1−/−;EphB2−/− compound homozygotes formed eTZs (arrows) in 7/7 SC analysed. (c) VT injected EphB1−/−;EphB2lacZ/+ compound mutants formed eTZs (arrows) in 16/21 SC analysed. (d) VT injected EphB1−/−;EphB2lacZ/lacZ compound homozygotes formed eTZs (arrows) in 6/8 SC analysed. (e) Graphic summary of the percent of SC that formed eTZs in mice injected in the dorsal or VT retina. Dorsal injected: WT (1%, n=87), EphB1−/−;EphB2+/− (10%, n=10), EphB1−/−;EphB2−/− (0%, n=7), EphB1−/−;EphB1lacZ/+ (0%, n=11), and EphB1−/−;EphB1lacZ/lacZ (0%, n=9). VT injected: WT (3%, n=109), EphB1−/−;EphB2+/− (100%, P<0.0001, n=12), EphB1−/−;EphB2−/− (100%, P<0.0001, n=7), EphB1−/−;EphB1lacZ/+ (76%, P<0.0001, n=21), and EphB1−/−;EphB1lacZ/lacZ (75%, P<0.0001, n=8). FET compared mutant groups with WT mice. Statistical significance is denoted by asterisks: *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01, and ***P≤0.001. Scale bar, 500 μm. C, caudal; L, lateral; M, medial; R, rostral.

Likewise, compound mutant mice carrying the EphB1− and EphB2lacZ alleles had near-full penetrance of mapping defects. Seventy-six percent (P<0.0001, FET, n=21) of the EphB1−/−;EphB2lacZ/+ and 75% (P<0.0001, FET, n=8) of the EphB1−/−;EphB2lacZ/lacZ mutant SC formed 1–6 eTZs that localized lateral, caudal, and lateral–caudal directions relative to the primary TZ (Fig. 5c,d). The primary TZs were also often not compact, and exhibited stray axonal projections.

Dorsal RGC axons formed no eTZs (n=7) in the EphB1−/−:EphB2−/− compound nulls, and only 1 (n=10) of the EphB1−/−;EphB2+/− SC analysed did so (Fig. 5e). Together, these data demonstrate the vital and specific role for EphB1/EphB2-mediated forward signalling in VT RGC axons.

Ephrin-B1 mediates VT RGC axon mapping within the SC

Elevated ephrin-B1 expression at the midline of the SC or optic tectum (OT) suggests the potential role of ephrin-B1 acting as a ligand to mediate VT RGC axon interstitial branching and termination in the medial SC4,13,14,15,16. In chick and Xenopus laevis, ephrin-B1 mRNA is expressed along the midline of OT13,14. In the mouse SC, ephrin-B1 protein is found in a high medial/low lateral gradient in the superficial layer at P0 (ref. 4), though recent analysis described ephrin-B1 uniformly expressed at P2 in the superficial and deeper layers of the SC15. Demonstrating the important role for this expression, ephrin-B1 ectopic expression in the chick OT disrupted the direction of ventral RGC axon interstitial branching resulting in ectopic axon terminations16. To determine whether the absence of ephrin-B1 expression affects retinocollicular mapping, we analysed germ-line protein-null mutant mice that carried a deletion in the X-linked ephrin-B1 gene17. DiI-labelled dorsal RGC axons from ephrin-B1+/− (n=4) and ephrin-B1−/y (n=17) mice had no retinocollicular mapping errors. However, VT RGC axons formed 1 eTZ in 25% (P=0.0128, FET, n=12) of the ephrin-B1−/y hemizygous male mice and in 33% (P=0.0213, FET, n=6) of the ephrin-B1+/− female mice, that were small and either caudal or lateral to the primary TZ (Fig. 6). These data indicate that ephrin-B1 expressed in the SC midline acts as ligand to mediate EphB1/EphB2 forward signal-driven VT RGC axon retinocollicular mapping, although the incomplete penetrance of the defect suggests that other ephrin molecules likely participate.

(a) VT injected ephrin-B1-/y hemizygous males formed eTZs (arrows) in 3/12 SC analysed. (b) VT injected ephrin-B1+/− heterozygous females formed eTZs (arrows) in 2/6 SC analysed. (c) Graphic summary of the percent of SC that formed eTZs in mice injected in the dorsal or VT retina. Dorsal injected: WT (1%, n=87), ephrin-B1−/y (0%, n=17), and ephrin-B1+/− (0%, n=4). VT injected: WT (3%, n=109), ephrin-B1−/y (25%, P=0.0128, n=12), and ephrin-B1+/− (33%, P=0.0213, n=6). FET compared mutant groups with WT mice. Statistical significance is denoted by asterisks: *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01, and ***P≤0.001. Scale bar, 500 μm. C, caudal; L, lateral; M, medial; R, rostral.

Dorsal and VT axons require ephrin-B2 reverse signalling

To study roles for ephrin-B2-mediated reverse signalling in the mouse, we analysed ephrin-B2lacZ mutants that express a C-terminal, intracellular truncated ephrin-B2–β-gal fusion protein. While unable to transduce reverse signals, the ephrin-B2–β-gal fusion protein can still act as a ligand to stimulate forward signalling18. Because ephrin-B2lacZ/lacZ homozygotes do not survive after birth, this allele was combined with a new mutation described here, ephrin-B26YFΔV. This ephrin-B26YFΔV allele carries point mutations in the exon that encodes the intracellular cytoplasmic tail that change the 6 tyrosine residues into phenylalanines and also deletes the C-terminal valine residue (Supplementary Fig. S1). As a result, this mutation expresses a protein that is properly localized to the cell surface (Supplementary Fig. S2) but is unable to become tyrosine phosphorylated or interact with either SH2 or PDZ domain-containing downstream signalling proteins. Previous studies have shown that similar mutations in ephrin-B1 and ephrin-B3 express proteins that lose their ability to transduce canonical ephrin-B reverse signals but maintain their ability to act as ligands to transduce forward signals in adjacent EphB-expressing cells19,20.

Ephrin-B2lacZ/+ males were mated to ephrin-B26YFΔV/+ females and the resulting offspring were analysed by DiI labelling of dorsal RGC axons. We observed the formation of 1–2 eTZs medial or medial-rostral to the primary TZ in 11% (P=0.0442, FET, n=28) of ephrin-B26YFΔV/+ SC, 8% (P=ns, FET, n=26) of the ephrin-B2lacZ/+ SC, and 27% (P=0.0015, FET, n=15) of the ephrin-B2lacZ/6YFΔV SC (Fig. 7). This demonstrates that ephrin-B2 reverse signalling is required for dorsal RGC axon retinocollicular mapping.

(a) Example of retinal flatmounts (inserts), SC whole mounts, and summary schematics of eTZs in WT specimens injected with DiI in the VT or dorsal retina. (b) Dorsal injected ephrin-B2lacZ/+ heterozygotes formed eTZs (arrows) in 2/26 SC analysed and those injected in the VT retina formed eTZs in 8/22 SC. (c) Dorsal injected ephrin-B2lacZ/6YFΔV mutants formed eTZs (arrows) in 4/15 SC analysed and those injected in the VT retina formed eTZs in 5/12 SC. (d) Graphic summary of the percent of SC that formed eTZs in mice injected in the dorsal or VT retina. Dorsal injected: WT (1%, n=87), ephrin-B26YFΔV/+ (11%, P=0.0442, n=28), ephrin-B2lacZ/+ (8%, n=26), and ephrin-B2lacZ/6YFΔV (27%, P=0.0015, n=15). VT injected: WT (3%, n=109), ephrin-B26YFΔV/+ (14%, P=0.0105, n=49), ephrin-B2lacZ/+ (36%, P<0.0001, n=22), and ephrin-B2lacZ/6YFΔV (42%, P=0.0002, n=12). FET compared mutant groups with WT mice. Statistical significance is denoted by asterisks: *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01, and ***P≤0.001. Scale bar, 500 μm. C, caudal; L, lateral; M, medial; R, rostral.

Whereas the gradient of ephrin-B2 expression is at an obviously lower level in the ventral retina compared with the dorsal retina, its ventral expression is evident at E17.5 and becomes more pronounced during the first postnatal week as observed at P0 and P8 (Fig. 1c). This indicates ephrin-B2 may also participate in ventral RGC axon retinocollicular mapping. Indeed, DiI tracing of VT RGC axons indicated 1–2 eTZs lateral or caudal to the primary TZ in 14% (P=0.0105, FET, n=49) of the ephrin-B26YFΔV/+ SC and 36% (P<0.0001, FET, n=22) of the ephrin-B2lacZ/+ SC (Fig. 7). The severity of the mapping defect increased in ephrin-B2lacZ/6YFΔV SC in which 42% (P=0.0002, FET, n=12) of the SC formed 1–3 eTZs lateral, caudal, and rostral relative to the primary TZ (Fig. 7). These data indicate a previously unanticipated role for ephrin-B2 reverse signalling in VT RGC retinocollicular mapping.

Discussion

As illustrated in the schematic (Fig. 8), we determined that EphB2 tyrosine kinase catalytic activity and EphB1 forward signalling are required for VT RGC axon retinocollicular mapping and that ephrin-B1 is their likely ligand. We further show that ephrin-B2 acts as a receptor to transduce reverse signals necessary for both dorsal and ventral RGC axon mapping.

(a) VT RGC axons in WT terminate in the medial SC and form a single compact TZ by P8. Red illustrates the subgroup of RGC axons labelled by DiI and their termination in the SC. Blue represents the EphB high ventral/low dorsal gradient in the retina, whereas the purple represents the high dorsal/low ventral ephrin-B2 gradient. Green shows the high medial expression of ephrin-B1 in the SC. C, caudal; D, dorsal; L, lateral; M, medial; R, rostral; V, ventral. (b) Subset of VT RGC axons in EphB single protein-null and forward signalling mutants formed 1–3 eTZs lateral and sometimes caudal to the primary TZ. (c) Subset of VT RGC axons in EphB1;EphB2 compound protein-null and forward signalling mutants formed 1–6 eTZs lateral, caudal, and caudal–lateral to the primary TZ. The primary TZ was often reduced, dispersed, and/or projected stray axons. (d) Subset of VT RGC axons in ephrin-B1 protein-null mutants formed 1 eTZ lateral to the primary TZ. The primary TZ was dispersed in these mutants. (e) Subset of VT RGC axons in ephrin-B2 reverse signalling mutants formed 1–2 eTZ caudal and sometimes lateral to the primary TZ. (f) Subset of dorsal RGC axons in ephrin-B2 reverse signalling mutants formed 1-2 eTZ medial to the primary TZ.

Fifty per cent or greater of the EphB1−/−, EphB1T-lacZ/T-lacZ, EphB2K661R/K661R, and EphB2lacZ/lacZ single mutant mice exhibited mapping defects, thus, demonstrating that EphB1 and EphB2 each have a critical role. However, when we analysed VT-labelled axons in EphB1−/−;EphB2−/− mutants, the mapping defect reached complete penetrance and had severely disrupted retinocollicular maps indicating EphB1/EphB2-mediated forward signalling is vital.

A role for the EphB receptor extracellular domain in stimulating reverse signalling is also evident. Whereas EphB1−/−;EphB2lacZ/lacZ and EphB1−/−;EphB2lacZ/+ mutants exhibited mapping defects as severe as those observed in the EphB1−/−;EphB2−/− mutants, the penetrance decreased from 100% to 75%. Furthermore, the EphB2−/− mutants displayed mapping defects that were less penetrant compared with the EphB2lacZ/lacZ and EphB2K661R/K661R mutants, whereas the EphB1−/− and EphB1T-lacZ/T-lacZ shared similar levels of penetrance. The presence of the EphB2 extracellular domain in the EphB2lacZ/lacZ and EphB2K661R/K661R mutants may disrupt the balance between reverse and forward signalling whereas the lack of EphB2 in EphB2−/− mutants may result in an overall decrease in both forward and reverse signalling rather than an imbalance. The extracellular domain of EphB1 may not be essential so that elimination of EphB1 in the EphB1−/− mutants results in disruption of only forward signalling resulting in an imbalance between forward and reverse signalling.

Another interesting observation is that the loss of kinase activity only affects VT axons, while the kinase-overactive gain-of-function EphB2F620D point mutant has both ventral and dorsal axons disrupted. EphB2 is expressed in the dorsal retina, albeit at relatively lower levels than in the ventral retina. Excessive unregulated kinase activity in the gain-of-function may have a much stronger effect in dorsal axons than loss of kinase activity, and this imbalance in signalling may cause them to behave more like VT axons leading to abnormal targeting.

Whereas other studies have highlighted the role of EphB3 using EphB2;EphB3 compound mutants4, we evaluated roles for EphB1, EphB2, and EphB3 individually and in compound mutants. The VT RGC axons in EphB2−/− and EphB3−/− single mutants formed eTZs in about 20% of the SC whereas EphB2−/−;EphB3−/− mutants formed eTZs in about 36% of the SC (Figs 2 and 3). Although these data indicate that EphB3 is important in ventral RGC axon retinocollicular mapping, the EphB2−/−;EphB3−/− mutants did not have the same severity or 100% penetrance as the EphB1−/−;EphB2−/− mutants.

VT RGC axons expressing high levels of EphB receptors target into the medial-rostral SC that expresses ephrin-B1. As hypothesized in other studies4 and examined in the chick16, ephrin-B1 likely attracts RGC axon interstitial branches to the midline. This attraction is likely balanced by repulsion to the midline mediated by Wnt–Ryk signalling3. Our data is the first to show a mapping defect in ephrin-B1 mutant mice that supports this hypothesis, although surprisingly ephrin-B1-deleted mutants do not disrupt retinocollicular mapping to the extent that the EphB1;EphB2 compound mutants do, indicating ephrin-B1 is not the sole ligand.

Ephrin-B2 reverse signalling mutants not only disrupted dorsal RGC axon mapping, as predicted by its robust dorsal expression pattern, but also VT RGC axons. Dorsal RGC axons lacking ephrin-B2 reverse signalling still express EphB receptors, therefore, EphB forward signalling may become the dominant signalling mechanism resulting in too much attraction to the midline thus eTZs that form medial to the primary TZ. VT RGC axons lacking ephrin-B2 reverse signalling seem to form more eTZs along the rostrocaudal axis as well as lateral to the primary TZ, indicating that the lack of ephrin-B2 reverse signalling disrupts VT RGC axon targeting to the rostral-medial SC.

Mediators for dorsal RGC axons in mice have not been found previously, although other studies show that ephrin-B2 reverse signalling is important for retinotopic mapping. In Xenopus laevis, ephrin-B2 mRNA is expressed in a high dorsal/low ventral gradient in the retina and along the midline of the OT14. Ectopic expression of a dominant-negative ephrin-B2 cytoplasmic tail deleted mutant in either the dorsal or ventral retina resulted in RGC axon targeting errors in the OT. Whereas this study in Xenopus and ours in mice show ephrin-B2 reverse signalling is important for dorsoventral RGC axon retinocollicular mapping, the ligand that ephrin-B2 interacts within the SC remains unknown. As the EphB1 and EphB2 single and compound null mutants showed no significant defect in dorsal RGC axon targeting, the data indicates these two Eph molecules are not acting as the principal ligands here to stimulate reverse signalling.

While we identified ephrin-B1 as a ligand for VT axons, other unknown ligands must be present to explain the penetrance of defects observed in the EphB and ephrin-B2 mutants. In addition, as mentioned above, no ligand that stimulates reverse signalling in dorsal RGC axons has been identified in the SC. One possibility is that receptor and ligands co-expressed on RGC axons interact in cis with each other and promote interstitial branch extension in the SC, or perhaps interact with Ephs and ephrins localized on adjacent axons. Another possibility is that EphB/ephrin-B2 expressed on the RGC axons interact with EphA/ephrin-A expressed in the SC. The Eph and ephrin molecules generally interact within their own class, however some interclass promiscuity exists. Both EphA4 and EphB2 bind to ephrin-B1/2/3 and ephrin-A5, as visualized by crystal structures of EphB2:ephrin-A5 and EphA4:ephrin-B2 (refs 21,22,23). Ephrin-A5 has a high caudal/low rostral gradient expression in the SC and is critical for axon pruning of the initial overshoot of the RGC axons past their proper TZ during the first postnatal week. Considering the established activation of EphB2 forward signalling by ephrin-A5 (ref. 21), VT RGC axons may be responding to the ephrin-A5 gradient. Likewise, ephrin-B2 may interact with EphA4, which is expressed in the SC24. Supporting this hypothesis is the localization of eTZs along the rostrocaudal axis observed in VT axons of EphB and ephrin-B2 mutants. These interactions may contribute to the formation of rostral and caudal eTZs relative to the primary TZ in EphB and ephrin-B mutant SC as well as why the deletion of ephrin-B1 does not result in a fully penetrant defect.

Methods

Mice

Generation of CD1 background EphB and ephrin-B mutant mice and genotyping by PCR have been described previously for the following alleles used: EphB1− (ref. 5), EphB1lacZ (ref. 5), EphB2− (ref. 6), EphB2lacZ (ref. 6), EphB2ΔVEV (ref. 11), EphB2K661R (ref. 11), EphB2K661RΔVEV (ref. 11), EphB2F620D (ref. 12), EphB3− (ref. 25), ephrin-B1loxP (ref. 17), ephrin-B2lacZ (ref. 8). The EphB1T-lacZ mutation inserts bacterial lacZ sequence in frame within exon 9 immediately following the codon corresponding to murine EphB1 amino acid #578 (ref. 7). The ephrin-B1− allele was generated by crossing the ephrin-B1loxP conditional allele to a transgenic mouse that expresses Cre recombinase in the germline. All experiments involving mice were carried out in accordance with the US National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Animals under an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol and Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-approved facility at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Approximately equal numbers of males and females were used in the analysis without any differences noted.

Generation of the ephrin-B26YFΔV mutation

To construct the targeting vector, a bacterial artificial chromosome contig encompassing genomic DNA surrounding ephrin-B2 exon 5, which encodes the entire intracellular domain of ephrinB2, was first assembled in pBeloBAC11 from genomic mouse DNA by combining lambda phage clones EB2.9 and EB2.22 using recombineering in Escherichia coli strain EL 250 (ref. 26). Using a pL452-based mini-targeting vector that contained a positive selection neo cassette, a WT 300 bp 5′-arm of exon 5, and a 1,200 bp 3′-arm containing base pair modifications corresponding to the desired 6YFΔV mutations (Y255F, Y307F, Y314F, Y319F, Y333F, Y334F, and Δ336 V) was recombined with endogenous ephrin-B2 sequence. A targeting vector was retrieved into pL254 (a modified form of pL253 with a 3′ TK and extra DT-A negative selection cassette and an AscI restriction enzyme site for linearization). R1 embryonic stem cells27 were electroporated, and colonies were screened by Southern blotting. Germline transmission was obtained from chimeric mice generated by blastocyst injection. The loxP floxed neo cassette was subsequently deleted in the mouse by crossing to a germline expressing Cre recombinase transgenic mouse. Genotypes were confirmed by sequencing and then PCR using the following primers: Forward: 5′-GGC GTT TAA AGA CGG ACA TAT AAC A-3′, Reverse: 5′-CCT CAA GGT CCA ATG CTC ATA C-3′.

Biotinylation assay

The anterior half of embryos collected at 17.5-days development (E17.5) from matings of ephrin-B2lacZ/+ males and ephrin-B26YFΔV/+ females were dissociated with trypsin, and the resulting cell suspension was plated and allowed to grow in vitro for 24 hours. Cells were then exposed to sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (Pierce no. 89881) to covalently link biotin to cell surface-exposed proteins, washed in growth media, and then total cell protein lysates were prepared in lysis buffer (1% Triton, 100mM NaCl, 50mM NaF, 50mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5) containing Complete (Roche) protease inhibitor cocktail. Streptavidin coated beads (Pierce) were used to pull down all biotinylated cell surface proteins, which were resolved on 6% Tris-glycine gels, transferred to PVDF (Millipore) membranes, and then immunoblotted with amino-terminal specific anti-ephrin-B2 (Neuromics) and anti-β-actin (Sigma) antibodies followed by secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson).

Histology and X-gal staining

Embryos and postnatal pups were anesthetized, decapitated, washed in phosphate buffer, embedded in OCT and frozen in a slurry of dry ice and ethanol. Blocks were stored at −80 °C until cryosectioned at 14 μm onto Superfrost Plus (Fisher) slides. Sections were fixed in lacZ fixation solution (0.2% gluteraldehyde, 5 mM EGTA pH 7.3, 2 mM MgCl2 in 0.1 M phosphate buffer) for 10 min followed by three 5 min washes in lacZ wash buffer (8 mM MgCl2, 0.08% Nonidet-P40 in 0.1 phosphate buffer). Sections were then stained in X-gal stain (2 ml of 25 mg ml−1 X-gal, 0.106 g potassium ferrocyanide, 0.082 g potassium ferricyanide in 50 ml wash buffer) overnight at 37°C. The next day, slides were washed twice for 5 min in lacZ wash buffer and fixed in 4% formalin for 5 min. After one wash for 5 min with PBS and then water, slides were immersed in Nuclear Fast Red for 45 s to label cell bodies. Slides were then washed for 10 min followed by ethanol dehydration, xylene clearing and slide cover mounting.

Axon tracing and analysis

Mice were anesthetized by hypothermia and DiI (Molecular Probes) solution (DiI crystals dissolved 5% in dimethylformamide) was injected into the dorsal or ventral peripheral retina at P6 as described previously4,15,28. On P8, pups were sacrificed, brains isolated, cortex removed, and contralateral SC whole mounts were analysed blind to genotype. Retinas from pups with DiI-labelled TZs in the SC were flatmounted to assess the injection site. Injection site was evaluated for position in relation to the four major eye muscles and containment of the DiI to the focal dorsal or ventral region desired. Flatmounted retinas and whole mount SC (boundaries determined by characteristic shape and location) were visualized using epifluorescence microscopy, CCD camera, and MetaVue software. DiI labelling of the optic tract path to the SC was observed at X2 and then the SC was visualized at X4 to evaluate the TZ(s) labelled. All results were analysed using the FET comparing the mutant to the wild-type group. Data was reported as distinct levels of significance (*P≤0.05; **P≤0.01, and ***P≤0.001).

Additional information

How to cite this article: Thakar, S. et al. Critical roles for EphB and ephrin-B bidirectional signalling in retinocollicular mapping. Nat. Commun. 2:431 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1445 (2011).

References

Sperry, R. W. Chemoaffinity in the orderly growth of nerve fiber patterns and connections. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 50, 703–710 (1963).

Feldheim, D. A. & O'Leary, D. D. Visual map development: bidirectional signaling, bifunctional guidance molecules, and competition. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a001768 (2010).

Schmitt, A. M. et al. Wnt-Ryk signalling mediates medial-lateral retinotectal topographic mapping. Nature 439, 31–37 (2006).

Hindges, R., McLaughlin, T., Genoud, N., Henkemeyer, M. & O'Leary, D. D. EphB forward signaling controls directional branch extension and arborization required for dorsal-ventral retinotopic mapping. Neuron 35, 475–487 (2002).

Williams, S. E. et al. Ephrin-B2 and EphB1 mediate retinal axon divergence at the optic chiasm. Neuron 39, 919–935 (2003).

Henkemeyer, M. et al. Nuk controls pathfinding of commissural axons in the mammalian central nervous system. Cell 86, 35–46 (1996).

Chenaux, G, & Henkemeyer, M. Forward signaling by EphB1/EphB2 interacting with ephrin-B ligands at the optic chiasm is required to form the ipsilateral projection. Euro. J. Neurosci. (in press).

Dravis, C. et al. Bidirectional signaling mediated by ephrin-B2 and EphB2 controls urorectal development. Dev. Biol. 271, 272–290 (2004).

Birgbauer, E., Cowan, C. A., Sretavan, D. W. & Henkemeyer, M. Kinase independent function of EphB receptors in retinal axon pathfinding to the optic disc from dorsal but not ventral retina. Development 127, 1231–1241 (2000).

Cowan, C. A., Yokoyama, N., Bianchi, L. M., Henkemeyer, M. & Fritzsch, B. EphB2 guides axons at the midline and is necessary for normal vestibular function. Neuron 26, 417–430 (2000).

Genander, M. et al. Dissociation of EphB2 signaling pathways mediating progenitor cell proliferation and tumor suppression. Cell 139, 679–692 (2009).

Holmberg, J. et al. EphB receptors coordinate migration and proliferation in the intestinal stem cell niche. Cell 125, 1151–1163 (2006).

Braisted, J. E. et al. Graded and lamina-specific distributions of ligands of EphB receptor tyrosine kinases in the developing retinotectal system. Dev. Biol. 191, 14–28 (1997).

Mann, F., Ray, S., Harris, W. & Holt, C. Topographic mapping in dorsoventral axis of the Xenopus retinotectal system depends on signaling through ephrin-B ligands. Neuron 35, 461–473 (2002).

Buhusi, M. et al. ALCAM regulates mediolateral retinotopic mapping in the superior colliculus. J. Neurosci. 29, 15630–15641 (2009).

McLaughlin, T., Hindges, R., Yates, P. A. & O'Leary, D. D. Bifunctional action of ephrin-B1 as a repellent and attractant to control bidirectional branch extension in dorsal-ventral retinotopic mapping. Development 130, 2407–2418 (2003).

Davy, A., Aubin, J. & Soriano, P. Ephrin-B1 forward and reverse signaling are required during mouse development. Genes Dev. 18, 572–583 (2004).

Cowan, C. A. et al. Ephrin-B2 reverse signaling is required for axon pathfinding and cardiac valve formation but not early vascular development. Dev. Biol. 271, 263–271 (2004).

Bush, J. O. & Soriano, P. Ephrin-B1 regulates axon guidance by reverse signaling through a PDZ-dependent mechanism. Genes Dev. 23, 1586–1599 (2009).

Xu, N. J. & Henkemeyer, M. Ephrin-B3 reverse signaling through Grb4 and cytoskeletal regulators mediates axon pruning. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 268–276 (2009).

Himanen, J. P. et al. Repelling class discrimination: ephrin-A5 binds to and activates EphB2 receptor signaling. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 501–509 (2004).

Chrencik, J. E. et al. Structural and biophysical characterization of the EphB4*ephrinB2 protein-protein interaction and receptor specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 28185–28192 (2006).

Qin, H. et al. Structural characterization of the EphA4-Ephrin-B2 complex reveals new features enabling Eph-ephrin binding promiscuity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 644–654 (2010).

Rashid, T. et al. Opposing gradients of ephrin-As and EphA7 in the superior colliculus are essential for topographic mapping in the mammalian visual system. Neuron 47, 57–69 (2005).

Orioli, D., Henkemeyer, M., Lemke, G., Klein, R. & Pawson, T. Sek4 and Nuk receptors cooperate in guidance of commissural axons and in palate formation. EMBO J 15, 6035–6049 (1996).

Liu, P., Jenkins, N. A. & Copeland, N. G. A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations. Genome Res. 13, 476–484 (2003).

Nagy, A., Rossant, J., Nagy, R., Abramow-Newerly, W. & Roder, J. C. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 8424–8428 (1993).

Simon, D. K. & O'Leary, D. D. Development of topographic order in the mammalian retinocollicular projection. J. Neurosci. 12, 1212–1232 (1992).

Acknowledgements

We thank Rebekkah Warren for assistance in generation of the ephrin-B26YFΔV targeting vector, Alice Davy and Phil Soriano for the ephrin-B1loxP conditional mutant mice, and Franny Prince for genotyping. This research was supported by the NIH (R01 EY017434).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T. performed all experiments. G.C. generated the ephrin-B26YFΔV and EphB1T-lacZ mutant mice. S.T. and M.H. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S2 (PDF 309 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thakar, S., Chenaux, G. & Henkemeyer, M. Critical roles for EphB and ephrin-B bidirectional signalling in retinocollicular mapping. Nat Commun 2, 431 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1445

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1445

This article is cited by

-

N,N-Dimethyl-3β-hydroxycholenamide attenuates neuronal death and retinal inflammation in retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting Ninjurin 1

Journal of Neuroinflammation (2023)

-

Extracellular phosphorylation drives the formation of neuronal circuitry

Nature Chemical Biology (2019)

-

Mechanisms of ephrin–Eph signalling in development, physiology and disease

Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology (2016)

-

EphB4 forward signalling regulates lymphatic valve development

Nature Communications (2015)

-

The role of endocytosis in activating and regulating signal transduction

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2012)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.