Abstract

Emerging large-area technologies based on organic transistors are enabling the fabrication of low-cost flexible circuits, smart sensors and biomedical devices. High-gain transistors are essential for the development of large-scale circuit integration, high-sensitivity sensors and signal amplification in sensing systems. Unfortunately, organic field-effect transistors show limited gain, usually of the order of tens, because of the large contact resistance and channel-length modulation. Here we show a new organic field-effect transistor architecture with a gain larger than 700. This is the highest gain ever reported for organic field-effect transistors. In the proposed organic field-effect transistor, the charge injection and extraction at the metal–semiconductor contacts are driven by the charge diffusion. The ideal conditions of ohmic contacts with negligible contact resistance and flat current saturation are demonstrated. The approach is general and can be extended to any thin-film technology opening unprecedented opportunities for the development of high-performance flexible electronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transistors fabricated with organic, polymeric, amorphous-oxide and carbon-based materials are the basis of emerging technologies for the development of lightweight, large-area and flexible electronics1,2,3,4,5,6. Large-area electronics manufactured at near-to-room temperature on plastic foils aims at enabling new applications where mechanical flexibility, integration in wrapping materials and ultra-low cost are paramount. To fabricate a transistor in flexible technologies, nanometre-thick layers of metals, insulators and semiconductor are stacked together and the semiconductor is directly contacted with the metal electrodes. The overall transistor performance intimately depends on three physical processes: the charge injection from the source electrode to the semiconductor, the charge transport through the semiconductor and the charge extraction at the drain electrode. The impressive development of high-mobility semiconductors7,8,9 and short channel-length transistors10,11 urgently demand high-quality contacts and proper transistor design12,13. Unfortunately, the energetic matching between abruptly contacted metal–semiconductor materials is challenging, especially at near-to-room temperature13. Electrons and holes must overcome large energy barriers to flow from a material to the other, resulting in a large contact resistance, large device-to-device variations and low transistor amplification13,14,15,16,17,18.

The figure-of-merit that determines the intrinsic amplification of a transistor is the gain=gm/go, where gm=∂ID/∂VG is the transconductance and go=∂ID/∂VD is the output conductance. High-gain transistors are essential for the development of large-scale and robust circuits, high-sensitivity sensors, and adequate signal amplification in sensing systems. Unfortunately, organic field-effect transistors (OFETs) typically show a gain of the order of tens17,18. The low gain measured in OFETs is due to the large contact resistance that results in a small gm and to the channel length modulation that results in a large go. Therefore, high-gain OFETs need, at the same time, both high-quality contacts and flat current saturation.

Ohmic contacts with small contact resistance require efficient charge injection and extraction. In organic electronics, the contact optimization is performed on a case-by-case basis, depending on the semiconductor, electrodes and device architecture. Despite ad-hoc approaches18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 such as doping, surface treatments and materials blending enable to reduce the contact resistance, a general and simple method is desirable. In addition, the channel length modulation dependents on the specific OFET architecture and geometries, which determine how the charge carriers are extracted at the drain17,18.

Here we show a new organic transistor with high-quality contacts and flat current saturation. Thanks to the charge diffusion triggered by the transistor architecture, the charge carriers are efficiently injected and extracted from the contacts to the channel, independently of the energy barrier at the contacts. As a prototype and remarkable example, we fabricate Diffusion-driven Organic Field-Effect Transistors (named DOFETs) on flexible plastic substrates with an industrial thin-film technology. The theoretical and experimental analysis unambiguously show that the diffusion-driven contact, proposed in this work for the first time, is fundamental to dramatically improve the charge injection and extraction in organic thin-film field-effect transistors. The ideal conditions of negligible contact resistance and fully flat current saturation are demonstrated. These conditions maximize together the transconductance and the output resistance of the transistors, resulting in OFETs with exceptionally high gain (>700).

Results

Structure and electrical characteristics of the transistor

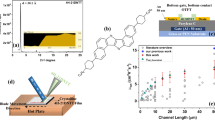

The top-view image and the three-dimensional structure of the diffusion-driven organic transistor are shown in Fig. 1a,b. The transistors are bottom-gate co-planar where the gate is patterned first by using photolithography. Thereafter, we deposited by spin coating a photoimageable polymer (polyvinylphenol) used as a gate insulator (named insulator 1) followed by gold source (S) and drain (D) electrodes patterned by a lift-off process. A 100-nm-thick film of pentacene is deposited by spin coating and patterned. A thick layer of polyvinylphenol (named insulator 2) is deposited by spin coating and used as insulator and capping layer. Finally, two electrodes named ‘control source’ (CS) and ‘control drain’ (CD) are patterned on the top of the insulator 2 in front of the source and drain electrodes. The transistors are fabricated on a plastic polyethylene naphthalate foil (Fig. 1c) and the overall process temperature is lower than 150 °C. Further details on the transistors fabrication and geometries are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The measured transfer and output curves are shown in Fig. 1d–f and Supplementary Fig. 2.

(a) Top-view optical image of a diffusion-driven organic field-effect transistor (DOFET) fabricated on plastic foil OSC is the organic semiconductor. Scale bar, 5 μm. (b) DOFET components. Photolithographically patterned gold is used for metal electrodes (named gate, source, drain, control source, control drain), the insulators (insulators 1 and 2) are photoimageable polymers (polyvinylphenol), and the organic semiconductor is a solution-processed pentacene. The material thicknesses are detailed in the Supplementary Fig. 1. (c) Photograph of the plastic (PEN) foil with the measured transistors detached from the glass substrate. The transistors are fabricated with an industrial thin-film technology with three metal layers. (d,e) Measured transfer characteristics at several control source voltages. The VCS step is 10 V, VS=0 V and VCD=0 V. The DOFET channel width and length are W=100 μm and L=12.5 μm, respectively. (f) Measured output characteristics at several control drain voltages.

Operation of the transistor

The DOFET operates as follow. An appropriate voltage applied to CS and CD, creates a vertical electric field orthogonal to the S/D contact surface. It triggers a charge injection from the upper surface of S/D into the semiconductor (Fig. 2a). In equilibrium (VS=VD=0 V, no current flows), the electric-field below CS/CD is counterbalanced by the injected-charges that are accumulated in the semiconductor region below CS/CD. When a source-drain voltage is applied (|VDS|>0), the charge carriers flow from source to drain despite the contact energy barriers and the potential drop at the contacts is negligible (Fig. 2b).

Two-dimensional numerical simulations. The applied voltages are VG=−5.1 V, VS=0 V, VD=−1 V, VCS=−60 V, VCD=−60 V. Geometrical and physical parameters are listed in the Supplementary Fig. 1 and in the Methods section, respectively. (a) Charge concentration in the organic semiconductor. The white arrows depict the charge injection from the source and drain electrodes into the semiconductor when the control source and control drain electrodes are biased. The x-to-y scale ratio is 1:200. (b) Quasi-Fermi potential at y=99 nm with (full line) and without (dashed line) CS/CD. Without CS/CD about half of VDS drops at the source and it is required for the charge injection. (c) Current density: x-component JX (black area) is equal to 1 A cm−2, and the y-component JY is shown with colour scale levels. (d) Current density JY and electric field EY along the y-direction at x=3.5 μm. In the range y=[0–47] nm, the current is driven by the diffusion, and in the range y=[47–100] nm, the current is driven by the drift. (e) JY and EY along the y-direction at x=20.5 μm. In the range y=[0–47] nm, the current is driven by the drift, and in the range y=[47–100] nm, the current is driven by the diffusion.

More in detail (Fig. 2c), the charge carriers accumulated in the CS region move to the right-edge of the CS region itself, attracted by the drain potential (Fig. 2c, arrow 2). As a consequence, the vertical electric field at the left-hand-side of the CS region is not shielded anymore and, despite the energy barrier, other charges can be injected by the source electrode (arrow 1). The excess of the charge carriers at the right-hand-side of the CS region are pushed to the bottom channel by the diffusion against the vertical electric field (arrow 3). As shown in Fig. 2d, few nanometres far from the CS region the vertical electric-field changes direction under the influence of the gate potential and the charge carriers are eventually pulled into the transistor channel (arrow 4). As a result, the CS region acts as an ideal source. The key physical mechanism triggered by the transistor architecture is the charge diffusion, which takes place in less than Ldiff=50 nm (Fig. 2d) when the semiconductor thickness is tS=100 nm. We also verified that the diffusion length scales accordingly with the semiconductor thickness (that is, Ldiff≅25 nm when tS=50 nm).

The charge carriers injected into the channel drift to the drain (Fig. 2c, arrow 5) under the force of the longitudinal electric field. When the charge carriers reach the right edge of the channel, they are blocked by the energy barrier at the drain contact, and the local concentration increases. The charges are no more counterbalanced by the gate electric field, and they can diffuse to the CD region (arrow 6) in correspondence of the CD region edge. As shown in Fig. 2e, few nanometres far from the channel the vertical electric field changes direction, the charge carriers are pulled into the CD region (arrow 7) and eventually diffuse (arrow 9) to the drain. The CD region acts as an ideal drain.

The idea is that in the DOFETs the charge injection and extraction do not take place directly from the source and drain metal electrodes as in conventional transistors but, instead, the charge carries are injected by the CS region and are extracted by the CD region. The injection and the extraction are driven by the diffusion triggered by the transistor architecture. As a result, when enough charge carriers are accumulated in the CS and CD regions, the charge injection and extraction are independent of the applied voltages (viz. VCS and VCD) and the CS and CD regions behave like ideal source and drain for the transistor channel. Therefore, as confirmed by the two-dimensional (2D) numerical simulations shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, the gate electrode is not required to overlap the source and drain electrodes.

The potential at the insulator1–organic interface calculated by means of 2D numerical simulations is shown in Fig. 2b. In the DOFET, the potential drop at the contacts is negligible even if the energy barrier at the metal–semiconductor contacts is 0.5 eV, that is a typical barrier at the metal–organic contacts. In contrast, in a conventional organic transistor (viz. without CS and CD), the charge carriers must overcome the energy barrier flowing from the channel to the S/D electrodes and vice versa. Owing to the energy barrier, the channel is disconnected from the S/D electrodes and more than the half of the drain voltage drops at the contacts (Fig. 2b). The large contact resistance severely limits the transistor performances and this is even worse in case of high-mobility semiconductors and/or short-channel lengths.

Experimental analysis

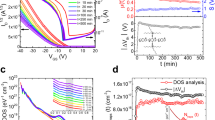

The effectiveness of the proposed approach is further assessed by means of the experimental results shown in Fig. 3. Figure 3a shows the measured contact resistance RP as a function of the gate voltage VG. The contact resistance of the DOFET biased at VCS=−40 V (that corresponds to an electric field |EY-VCS|=0.28 MV cm−1) is equal to RP[DOFET]=20 kΩ cm, which is lower than the contact resistance in conventional OFETs with Au-pentacene-doped contacts20 and, more importantly, RP[DOFET] is independent of VG. In contrast, the contact resistance of an organic transistor without CS/CD (conventional coplanar transistor) fabricated with the same materials and process is VG dependent. It is up to 24 times larger than that of the DOFET and, even at large gate voltages (VG=−25 V, that is, |EY−VG|=0.7 MV cm−1), RP[OFET]>5 × RP[DOFET]. Analogous results are obtained comparing the DOFET with a conventional staggered OFET (Supplementary Fig. 4).

When it is not specified, the applied voltages are: VS=0 V, VD=−1 V, VCS=0 V, VCD=0 V, and the transistors geometries are: W=100 μm, L=12.5 μm. (a) Width-normalized contact resistance RP as a function of the gate voltage VG. RP is calculated with the method26. In the conventional OFET (viz. without CS and CD), RP decreases with VG, whereas in the DOFET, RP is independent of VG. When the control source is biased at VCS=+5 V, the DOFET works as a conventional coplanar OFET. (b) RP vs VCS at various VG measured on two nominally identical DOFETs. When VCS<−10 V, RP is the same for both the DOFETs and it is independent of both VG and VCS. Inset: measured output characteristics of a DOFET at several VCS. (c) Maximum overall field-effect mobility vs VCS. The inset shows the field-effect mobility as a function of the gate voltage: μFE=(L/W) (∂ID/∂VG)/(Ci VD). The × symbol is the maximum value of each curve. (d) Threshold voltage (VTH) as a function of VCS. VTH is the intercept to the VG-axis of the ID linear fit. Inset: Subthreshold slope as a function of VCS. (e) Normalized output characteristics of the DOFET measured at various VCD. ID is normalized by its maximum value at VD=−30 V. In saturation, the DOFET is an ideal current generator because the current is diffusion driven. The most important short-channel effect due to the channel-length modulation vanishes. The VCD controls the charge extraction at the drain electrode, which has a strong impact on the output conductance (gO=∂ID/∂VD). (f) Normalized output characteristics of a DOFET and two conventional OFETs (viz. without CS and CD).

To give more insight, Fig. 3b shows the RP-VCS characteristic of two nominally identical DOFETs for several VG. RP is controlled by VCS despite the gate voltage. Indeed, at low gate voltage (VG=−5 V, that is, |EY-VG|=0.14 MV cm−1), VCS modulates RP by more than four orders of magnitude, and at large VG=−20 V (|EY-VG|=0.57 MV cm−1), RP still depends on VCS. Interestingly, when VCS<−20 V (that is, |EY-VCS|=0.14 MV cm−1) the contact resistance is negligible compared with the channel resistance (Supplementary Fig. 5) and it is independent of both VG and VCS. As confirmed by the measurements shown in the inset of Fig. 3b, this is the experimental evidence that the current enhancement originates from the improved charge injection at the source. According to the physical insight obtained by means of the 2D numerical simulations, at VCS<−20 V, the accumulated CS-region is an ‘infinite’ charge reservoir, the charge diffusion efficiently sustain the charge injection required by the channel, and the CS-region behaves like an ohmic contact. On the other hand, at VCS>+5 V, the diffusion-driven charge injection is turned-off, the contact resistance increases, the drain current lowers and it increases super-linearly with VD as usually obtained in contact limited transistors13,15,16,19. We can conclude that it is possible to control (enhance or reduce) the charge injection at the source contact through nanometre-scale charge diffusion.

Comparing the RP obtained for two nominally identical DOFETs (Fig. 3b), it results that when the virtual-ohmic source contact is not formed, the transistors show different RP, whereas as soon as the virtual-ohmic source contact is formed (VCS<−20 V), RP becomes the same for both the DOFETs. According to refs 10, 12, 13, these measurements suggest that the metal–organic contact is a source of variability. As the DOFET suppresses the contact resistance, the variability due to RP is reduced as well. This feature is essential for the large-scale integration of flexible circuits. Moreover, the improved charge injection results in a larger overall field-effect mobility (Fig. 3c) as well as in a reduced threshold voltage (Fig. 3d) and steeper subthreshold slope (inset Fig. 3d). Figure 3c shows that the maximum mobility of a DOFET with L[DOFET]=12.5 μm is close to 0.1 cm2 V−1 s−1 and it corresponds to the mobility measured in long-channel OFETs (L[OFET]=100 μm), where the contact resistance is negligible. Figure 3d shows that by means of VCS the DOFET can be turned into a multi-threshold transistor and the improved DOFET (VCS<−20 V) operates in depletion-mode. In unipolar technologies, depletion-mode transistors are essential to design high-performance circuits27,28 and the electrical control of the threshold voltage is extremely important to improve the circuit robustness27,28,29.

When the transistor operates in linear region, the energy barrier at the drain side of the channel is smaller than that at the source side. On the other hand, in saturation (|VG|<|VD|), a wider energy barrier is present at the drain, independently of the metal/semiconductor properties (Fig. 4a). Therefore, we investigated the impact of the control drain in saturation. The output characteristics (ID–VD) of the DOFET measured at various VCD are shown in Fig. 1f. As expected, ID increases with VCD and, more importantly, at large (negative) VCD the DOFET shows fully flat current saturation. The impact of VCD on the current saturation is readily visible in Fig. 3e where the ID–VD characteristics are normalized with respect to the maximum ID measured at VD=−30 V. At VCD<−40 V, the detrimental effect of the channel length modulation on the drain current is completely suppressed and the DOFET behaves like an ideal current generator.

The applied voltages are VG=−5.1 V, VS=0 V, VD=−10 V, VCS=−60 V, VCD=−60 V. (a) Charge concentration in the organic semiconductor. (b) Current density: x-component JX (black area) is equal to 1 A cm−2, and the y-component JY is shown with colour scale levels. For the sake of clarity, the positions of control source (CS), control drain (CD) and gate electrodes are shown. Geometrical and physical parameters are listed in the Supplementary Fig. 1.

This can be explained in the light of the previous analysis. In saturation, the charge carriers drift to the right-edge of the channel (pinch-off region), and diffuse to the CD region (Fig. 4b, arrow 6). Few nanometres far from the channel edge, the vertical electric-field changes direction because of the control drain voltage and, in turn, the charge carriers are pulled into the CD region (arrow 7). Now, the excess charges are no more in equilibrium with the vertical electric-field and can diffuse to the drain (arrow 9). As the charge-extraction from the accumulated layer (viz. CD region) is diffusion driven, the drain current is independent of the drain voltage as far as VCD is greater than VD.

Figure 3f shows the comparison between a DOFET with a channel length L[DOFET]=12.5 μm (full line), and two conventional coplanar OFETs with L[OFET1]=12.5 μm (red dashed line) and L[OFET2]=100 μm (black dashed line). Interestingly, the channel length modulation of the DOFET biased at VCD=−60 V is completely suppressed: it is even smaller than that of the long-channel OFET2. This is also more evident when the DOFET is compared with a conventional staggered OFET (Supplementary Fig. 6) where the channel length modulation is very large because the source and drain electrodes are placed at the opposite side of the gate. These results confirm that VCD controls channel length modulation and in turn the output resistance of the DOFET. The channel length modulation is one of the most important short-channel effects and it limits the transistor amplification.

Figure 5 shows the maximum gain measured in a DOFET as a function of VCD (full line with symbols). According to Figs 1f and 3e, the gain depends on VCD because it controls both the contact resistance at the drain and the channel length modulation. When VCD=−60 V, the gain is larger than 700. This is the largest gain ever reported for OFETs. It is one order of magnitude larger than the gain usually obtained in OFETs11,16,17,18,30,31,32,33,34,35.

Measured gain as a function of VCD. The applied voltages are VG=−5 V, VS=0 V, VCS=−20 V. The transistors width is W=100 μm. The DOFET (full line with symbols) length is L=12.5 μm. The OFET lengths are L=12.5 μm (red dashed line) and L=100 μm (black dashed line). The other geometries are the same. The DOFET and OFET are fabricated with the same materials (Supplementary Fig. 1). The grey area shows the gain obtained in OFETs11,16,17,18,30,31,32,33,34,35.

Discussion

The ultra-high gain measured in the DOFET is achieved thanks to the diffusion-driven charge injection and extraction. In particular, when the CS and CD regions are accumulated, they act as ideal contacts for the channel and the diffusion enables the efficient and voltage-independent charge injection and extraction. In the DOFET, the CS and CD regions are at the opposite side of the channel and resemble a staggered OFET with ideal ohmic contacts. It is important to note that in the DOFET this condition is always achieved, thanks to the accumulated CS and CD regions. The charge flow from/to the CS/CD regions and the channel is driven by the charge diffusion, and thus the contact resistance is independent of the gate (Fig. 3a) and drain (inset Fig. 3b) voltages, the saturation current is independent of VD, and an ultra-high gain is obtained.

As a comparison, the gain measured in the conventional OFET1 (L[OFET1]=12.5 μm, red dashed line) and OFET2 (L[OFET2]=100 μm, black dashed line) are shown in Fig. 5. As expected in both cases, the gain is much lower than that measured in the DOFET at any VCD because in the OFET1 the current is contact limited and the channel modulation is large, whereas in the OFET2 the contact resistance is negligible but the channel length is large and hence gm is small. In OFETs, the contact resistance can be reduced by means of the contact engineering and optimization18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, and the proper choice of the transistor architecture36,37. Indeed, staggered OFETs are more tolerant to the contact resistance with respect to the coplanar OFETs because in the staggered transistors the contact area (of the order of microns) is larger than that of coplanar transistors (of the order of nanometres). On the other hand, in staggered transistors the source and drain electrodes are at the opposite side of the channel and, when operated in saturation, the channel length modulation is larger than that in coplanar OFETs. As an alternative approach, the split-gate OFETs33,34 are based on a coplanar architecture and lower the contact resistance thanks to the gate bias-assisted charge injection38. However, the channel length modulation is not suppressed because the secondary gates are coplanar with the source and drain electrodes, the charge extraction is not diffusion driven and, as a result, the gain is comparable with that typically measured in OFETs (of the order of tens).

In addition to the high-gain, another advantage offered by the DOFET is the possibility to maximize the charge injection/extraction area at the source and drain electrodes, whereas minimizing the overlap between the gate and the electrodes. The 2D numerical simulations in Supplementary Fig. 3 and Fig. 6 show that the gate is not required to overlap the source and drain electrodes because the charge injection/extraction takes place from/to the CS/CD accumulated regions. At the same time, the CS and CD electrodes can be overlapped (without the drawback of extra capacitance) with the source and drain electrodes in order to exploit the full area of the electrodes that is typically in the range 5–10 μm (in our DOFET it is 5 μm). Thanks to the charge diffusion, taking place at the edge of the accumulated CS and CD regions, also the overlap between the gate and the CS and CD electrodes is not required. Moreover, the numerical simulations in Fig. 6 show that the equivalent contact length where the charges are injected/extracted is only LC=0.25 μm, which is suitable for the megahertz operation11.

Current density: x-component JX (black area) is 10 A cm−2, and the y-component JY is shown with colour scale levels. For the sake of clarity, the positions of control source (CS), control drain (CD) and gate electrodes are shown. Geometrical and physical parameters are listed in the Supplementary Fig. 1. The applied voltages are VG=−5.1 V, VS=0 V, VD=−1 V, VCS=−60 V, VCD=−60 V.

Finally, it is worth noting that the voltages required to form the charge-accumulated CS and CD regions are independent of the DOFET operation. For example, by setting VCS=VCD=−40 V, the DOFET operates as a conventional OFET with ideal ohmic contacts and ultra-high gain. Therefore, the two control electrodes can be connected together and the external circuit design and lines required for the proposed transistor structure is the same of that required for dual-gate transistors. The latter have been successfully used to fabricate an organic microprocessor with 3,381 dual-gate OFETs39. Moreover, an alternative approach is to replace the CS and CD electrodes with fixed charges trapped into the insulator 2 (ref. 40). Another very interesting approach would be the replacement of both the CS and CD electrodes and the insulator 2 with electric dipoles (Supplementary Fig. 7) by local molecular self-assembly functionalization41,42 of the top surface of the organic semiconductor in front of the source and drain electrodes.

In summary, the DOFET shows that it is possible to dramatically enhance the charge injection and extraction at the metal/semiconductor contacts by means of the nanometre-scale charge diffusion. The enhanced charge injection allowed us to reduce the threshold voltage by more than 15 V, and to increase the field-effect mobility about ten times, approaching the organic semiconductor transport limit also in short-channel transistors. The enhanced charge extraction enables the complete suppression of the channel-length modulation. We show that a short-channel DOFET behaves like an ideal current generator: its channel-length modulation is even smaller than that of an eight times longer organic transistor fabricated in the same technology. These features lead to the fabrication of high performance organic transistors with a unique benefits combination: negligible contact resistance, small device-to-device variability, and exceptionally high gain (>700).

Thanks to the transistor here proposed we theoretically explain and experimentally demonstrate for the first time that the charge diffusion can play a crucial role in organic transistors. Moreover, the ability to independently enhance or reduce the charge injection, transport and extraction in organic semiconductors makes the DOFET the ideal test-bed to study the fundamental physical processes taking place in organic semiconductors and at the metal–organic interfaces.

The proposed approach is a universal method to obtain high-quality contacts without the need of materials or process optimizations. Moreover, according to the approach proposed in ref. 43, the DOFET combined with ambipolar semiconductors could be used to electrically enhance the charge injection of one charge type and to suppress the other. This feature is very relevant for the low-cost fabrication of high-gain and low-power ambipolar complementary electronics.

The diffusion-driven organic transistor opens up new opportunities for the large-scale integration of flexible electronics, high-sensitivity sensors and ultra-large signal amplification in sensing systems.

Methods

Two-dimensional numerical simulations

The coupled drift–diffusion, Poisson and current continuity equations are solved together43,44,45. The simulation parameters are the following: relative permittivity of semiconductor ɛrs=3, relative permittivity of insulators (1 and 2) ɛri=3.757, highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) energy level EHOMO=2.8 eV, lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy level ELUMO=5.2 eV, effective density of HOMO states NHOMO=1021 cm−3, effective density of LUMO states NLUMO=1021 cm−3, holes effective mobility μh=0.1 cm2 V−1 s−1, electrons effective mobility μe=0.1 cm2 V−1 s−1, metal electrodes work function Φm=4.7 eV (the hole energy barrier at the source/drain metal-semiconductor is ΦB=0.5 eV), Schottky barrier lowering ΔΦB=e [e E/(4 π ɛ0 ɛrs)]^(1/2), where e is the elementary charge, E is the electric field and ɛ0 is the vacuum permittivity.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Torricelli, F. et al. Ultra-high gain diffusion-driven organic transistor. Nat. Commun. 7:10550 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10550 (2016).

References

Kaltenbrunner, M. et al. An ultra-lightweight design for imperceptible plastic electronics. Nature 499, 458–463 (2013).

Nomura, K. et al. Room-temperature fabrication of transparent flexible thin-film transistors using amorphous oxide semiconductors. Nature 432, 488–492 (2004).

Cao, Q. et al. Medium-scale carbon nanotube thin-film integrated circuits on flexible plastic substrates. Nature 454, 495–500 (2008).

Kuribara, K. et al. Organic transistors with high thermal stability for medical applications. Nat. Commun 3, 1–7 (2012).

Takei, K. et al. Nanowire active-matrix circuitry for low-voltage macroscale artificial skin. Nat. Mater. 9, 821–825 (2010).

Gelinck, G. H. et al. Flexible active-matrix displays and shift registers based on solution-processed organic transistors. Nat. Mater. 3, 106–110 (2005).

Minemawari, H. et al. Inkjet printing of single-crystal films. Nature 475, 364–367 (2011).

Yan, H. et al. A high-mobility electron-transporting polymer for printed transistors. Nature 457, 679–686 (2009).

Yuan, Y. et al. Ultra-high mobility transparent organic thin film transistors grown by an off-centre spin-coating method. Nat. Commun 5, 1–9 (2014).

Palfinger, U. et al. Fabrication of n- and p-type organic thin film transistors with minimized gate overlaps by self-aligned nanoimprinting. Adv. Mater. 22, 5115–5119 (2010).

Ante, F. et al. Contact resistance and megahertz operation of aggressively scaled organic transistors. Small 8, 73–79 (2012).

Arias, A. C., MacKenzie, J. D., McCulloch, I., Rivnay, J. & Salleo, A. Materials and applications for large area electronics: solution-based approaches. Chem. Rev. 110, 2–24 (2010).

Natali, D. & Caironi, M. Charge injection in solution-processed organic field-effect transistors: physics, models and characterization methods. Adv. Mater. 24, 1357–1387 (2012).

Li, L. et al. The electrode’s effect on the stability of organic transistors and circuits. Adv. Mater. 24, 3053–3058 (2012).

Léonard, F. & Talin, A. A. Electrical contacts to one- and two-dimensional nanomaterials. Nat. Nanotech 6, 773–783 (2011).

Valletta, A. et al. Contact effects in high performance fully printed p-channel organic thin film transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 233309 (2011).

Raiteri, D., Cantatore, E. & Van Roermund, A. H. M. Circuit Design on Plastic Foils Springer International Publishing (2015).

Klauk, H. Organic Electronics II: More Materials and Applications Wiley-VCH (2012).

Ante, F. et al. Contact doping and ultrathin gate dielectrics for nanoscale organic thin-film transistors. Small 7, 1186–1191 (2011).

Schaur, S., Stadler, P., Meana-Esteban, B., Neugebauer, H. & Sariciftci, N. S. Electrochemical doping for lowering contact barriers in organic field effect transistors. Org. Electron. 13, 1296–1301 (2012).

Gwinner, M. C., Jakubka, F., Gannott, F., Sirringhaus, H. & Zaumseil, J. Enhanced ambipolar charge injection with semiconducting polymer/carbon nanotube thin films for light-emitting transistors. ACS Nano 6, 539–548 (2012).

Asadi, K., Gholamrezaie, F., Smits, E. C. P., Blom, P. W. M. & De Boer, B. Manipulation of charge carrier injection into organic field-effect transistors by self-assembled monolayers of alkanethiols. J. Mater. Chem. 17, 1947–1953 (2007).

Hamadani, B. H., Corley, D. A., Ciszek, J. W., Tour, J. M. & Natelson, D. Controlling charge injection in organic field-effect transistors using self-assembled monolayers. Nano Lett. 6, 1303–1306 (2006).

Liu, Z., Kobayashi, M., Paul, B. C., Bao, Z. & Nishi, Y. Contact engineering for organic semiconductor devices via Fermi level depinning at the metal-organic interface. Phys. Rev. B 82, 035311 (2010).

Chai, Y. et al. Low-resistance electrical contact to carbon nanotubes with graphitic interfacial layer. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 59, 12–19 (2012).

Torricelli, F., Ghittorelli, M., Colalongo, L. & Kovacs-Vajna, Z. M. Single-transistor method for the extraction of the contact and channel resistances in organic field-effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 093303 (2014).

Nausieda, I. et al. Dual threshold voltage organic thin-film transistor technology. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 57, 3027–3032 (2010).

Raiteri, D. et al. A 6 b 10 MS/s current-steering DAC manufactured with amorphous Gallium-Indium-Zinc-Oxide TFTs achieving SFDR>30 dB up to 300 kHz. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. Digest of Technical Papers 55, 314–315 (2012).

Cosseddu, P., Vogel, J.-O., Fraboni, B., Rabe, J. P., Koch, N. & Bonfiglio, A. Continuous tuning of organic transistor operation from enhancement to depletion mode. Adv. Mater. 21, 344–348 (2009).

Li, Y. et al. Quick fabrication of large-area organic semiconductor single crystal arrays with a rapid annealing self-solution-shearing method. Sci. Rep 5, 13195 (2015).

Abdinia, S. et al. Variation-based design of an AM demodulator in a printed complementary organic technology. Org. Electron. 15, 904–912 (2014).

Lassnig, R. et al. Optimizing pentacene thin-film transistor performance: temperature and surface condition induced layer growth modification. Org. Electron. 26, 420–428 (2015).

Nakayama, K., Hara, K., Tominari, Y., Yamagishi, M. & Takeya, J. Organic single-crystal transistors with secondary gates on source and drain electrodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 153302 (2008).

Hsu, B. B. Y. et al. Split-gate organic field effect transistors: control over charge injection and transport. Adv. Mater. 22, 4649–4653 (2010).

Rapisarda, M. et al. Analysis of contact effects in fully printed p-channel organic thin film transistors. Org. Electron. 13, 2017–2027 (2012).

Shim, C.-H., Maruoka, F. & Hattori, R. Structural analysis on organic thin-film transistor with device simulation. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 57, 195–200 (2010).

Street, R. A. & Salleo, A. Contact effects in polymer transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 2887–2889 (2002).

Brondijk, J. J., Torricelli, F., Smits, E. C. P., Blom, P. W. M. & De Leeuw, D. M. Gate-bias assisted charge injection in organic field-effect transistors. Org. Electron. 13, 1526–1531 (2012).

Myny, K. et al. An 8-Bit, 40-instructions-per-second organic microprocessor on plastic foil. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 47, 284–291 (2012).

Huang, C., West, J. E. & Katz, H. E. Organic field-effect transistors and unipolar logic gates on charged electrets from spin-on organosilsesquioxane resins. Adv. Funct. Mater. 17, 142–153 (2007).

Calhoun, M. F., Sanchez, J., Olaya, D., Gershenson, M. E. & Podzorov, V. Electronic functionalization of the surface of organic semiconductors with self-assembled monolayers. Nat. Mater. 7, 84–89 (2008).

Hirata, I. et al. High-resolution spatial control of the threshold voltage of organic transistors by microcontact printing of alkyl and fluoroalkylphosphonic acid self-assembled monolayers. Org. Electron. 26, 239–244 (2015).

Torricelli, F. et al. Ambipolar organic tri-gate transistor for low-power complementary electronics. Adv. Mater. 28, 284–290 (2016).

Mariucci, L. et al. Current spreading effects in fully printed p-channel organic thin film transistors with Schottky source-drain contacts. Org. Electron. 14, 86–93 (2013).

Brondijk, J. J., Spijkman, M., Torricelli, F., Blom, P. W. M. & de Leeuw, D. M. Charge transport in dual-gate organic field-effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 023308 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from the Dutch Technology Foundation STW, which is the Applied Science Division of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), and by the Technology Programme of the Ministry of Economic Affairs. We also thank the Polymer Vision for the transistors fabrication. F.T. and D.R. thank Holst Centre for the patent application submission. F.T. thank Matteo Ghittorelli for the useful discussions, suggestions and for his contribution to Figure 2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.T. conceived the DOFET architecture, designed the devices, performed the 2D numerical calculations, measured the transistors, analysed the data, developed the physical analysis and wrote the manuscript. L.C. contributed to the physical analysis and wrote the manuscript. D.R. contributed to the DOFET architecture idea and performed the measurements. Z.M.K.-V. contributed to the performance analysis, supported the manuscript preparation and revised the manuscript. E.C. supervised the project and revised the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-7 and Supplementary References (PDF 850 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Torricelli, F., Colalongo, L., Raiteri, D. et al. Ultra-high gain diffusion-driven organic transistor. Nat Commun 7, 10550 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10550

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10550

This article is cited by

-

Electrolyte-gated transistors for enhanced performance bioelectronics

Nature Reviews Methods Primers (2021)

-

Multiscale real time and high sensitivity ion detection with complementary organic electrochemical transistors amplifier

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Nonvolatile switchable resistive behaviour via organic–inorganic hybrid interactions

Journal of Materials Science (2019)

-

Centimetre-scale electron diffusion in photoactive organic heterostructures

Nature (2018)

-

A Pulse-Biasing Small-Signal Measurement Technique Enabling 40 MHz Operation of Vertical Organic Transistors

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.