Abstract

Occult invasive and intraepithelial carcinomas have been identified in the tubal fimbria of BRCA mutation carriers undergoing prophylactic surgery, and recently described lesions overexpressing p53 in the distal tubes of mutation carriers, and non-carriers, have been proposed as histological precursors of high-grade serous carcinoma. The aim of this study was to confirm these findings in a larger, independent case set, to further characterize the cancer precursor lesions, and to determine their frequency in BRCA mutation-positive (n=176) and control groups (n=64). For the purposes of this study, we excluded cases without documentation of a germline mutation of BRCA1/2, and without histological examination of the entire tube, and cases with a diagnosis of invasive carcinoma. Controls included salpingectomies from women undergoing surgery for reasons other than ovarian malignancy. Diagnostic categories were assigned based on combined histological review and immunostaining results. Histological abnormalities were identified in 23% of the BRCA group and in 25% of the control group, and included localized p53 overexpression in 20% of the BRCA group and 25% of the control group. Tubal intramucosal carcinoma was identified in 8% of the BRCA cases and in 3% of the control group. Four cases of intraepithelial carcinoma (21%) did not overexpress p53. There was no significant difference in the median age, frequency of histological abnormalities, p53 signatures, or tubal intraepithelial carcinoma between the BRCA mutation-positive and control groups. This large, blinded review of tubes from BRCA mutation carriers confirms previous reports of putative cancer precursors in distal tubal mucosa, and that p53 signatures occur with similar frequency in women at low and high genetic risk of tubal/ovarian carcinoma. Tubal intraepithelial carcinoma, which, like invasive serous cancer, usually but not always overexpresses p53 protein, is more frequent in BRCA mutation carriers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

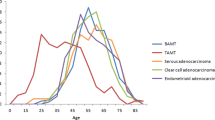

High-grade serous carcinoma is the most common type of ovarian cancer, accounting for 60–70% of all common epithelial malignancies. Unlike the other major histological types, endometrioid, clear cell, and mucinous carcinomas, it is infrequently diagnosed while confined to the ovary.1 Little is known of the genetic/molecular events which precede the advanced stage serous carcinoma, and until recently, reproducible histological precursors did not exist. A careful histological examination of ovaries and fallopian tubes prophylactically resected from BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers has provided clues to the existence of cancer precursor lesions in women genetically predisposed to high-grade serous carcinoma, and they have been identified not in the ovary, but in the distal fallopian tube epithelium.2, 3, 4, 5

Ovarian surface epithelium and epithelial inclusions within the ovarian cortex, acquired during reproductive life, have been the favored cell of origin for ovarian epithelial malignancies.6, 7 High-grade serous carcinoma is the type of ovarian cancer most frequently diagnosed in BRCA mutation carriers, and it was proposed that histological examination of these ‘cancer prone’ ovaries would reveal cancer precursors.8 However, blinded histological studies from multiple centers failed to reproducibly identify histological precancerous lesions in the high-risk ovaries.9, 10, 11 Although the identification of serous cancer precursor lesions in the ovary has been elusive, we and others have documented occult carcinomas in the ovaries and fallopian tubes of women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations undergoing prophylactic surgery, with a significant proportion of these early cancers present in the fallopian tube and not the ovary.12, 13, 14, 15

Fallopian tube epithelium in the premenopausal woman frequently shows some degree of epithelial proliferation, a finding considered to be within normal limits.16 Reports describing abnormalities of the tubal epithelium have used various terminologies, including dysplasia, atypical hyperplasia, and mucosal epithelial proliferations, but until recently, there has been no attempt at defining a serous cancer precursor within tubal mucosa.17, 18, 19 Using rigorous histological examination of fallopian tubes from BRCA mutation carriers, from women with ovarian malignancies, and from women considered to be at low (population) risk of developing ovarian cancer, Dr Crum et al have recently described histological and immunohistochemistry characteristics of tubal intraepithelial carcinomas and putative cancer precursors.4, 5 The candidate cancer precursors, p53 signatures, are morphologically benign, with overexpression of p53 and a low proliferative index.20 Located in the distal or fimbriated end of the fallopian tube, they are found not only in the epithelium of mutation carriers but also in the tubal epithelium of women with diagnoses of ovarian or primary peritoneal serous carcinoma. These discoveries suggest that the cell of origin for many high-grade serous carcinomas is in the fallopian tube and not the ovary, and that this may be the case not only in hereditary ovarian cancer but also in at least some cases of sporadic serous carcinoma.21

Approximately 50 risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomies are performed each year at our institution. We have noted the existence of focal lesions of distal tubal epithelium in our clinical practice, and have also noted the frequent association with p53 overexpression.2 Our aim in this study was to attempt to validate the findings of Crum et al in a larger series of prophylactic salpingectomies from BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, compare them with those of control cases, and to further characterize these putative cancer precursors by histological assessment and by immunohistochemistry.

Materials and methods

A total of 268 prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies were carried out at our institution between January 1992 and December 2006. The protocol for examining the resected ovaries and tubes has evolved with increasing recognition of the tubal pathologies in this high-risk population. Cases were included in this study based on known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation status, and were excluded if the fallopian tube was not submitted in toto for histological examination. As this study is primarily focused on putative cancer precursors, we also excluded cases with invasive carcinoma of the ovary, tube, or the peritoneum. A control group was included in this study, and consisted of bilateral salpingectomy specimens from women undergoing surgery for reasons other than ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal malignancy, and who were determined to be at low risk of ovarian carcinoma on the basis of medical and family history. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of University Health Network.

The age and mutation status of all patients are summarized in Table 1. In all cases included in the study, the fallopian tube was serially sectioned at 2- to 3-mm intervals after formalin fixation and submitted in toto for histological examination. In 146 of the BRCA cases and all of the control cases, a 2-mm cross-section of the fallopian tube proximal to the infundibulum was snap frozen and banked for research purposes. Although in all cases the fimbriated end was examined histologically, the SEE-FIM protocol proposed by Medeiros et al5 was not used in the majority.

All cases were randomized and were assigned a study number. All available sections of fallopian tube were submitted for immunohistochemistry for p53 (Novocastra) and Ki67 (Labvision) using standard techniques. All H&E sections were reviewed by a gynecological pathologist (PS), blinded to mutation status and diagnosis. Cases were scored as p53 positive if greater than 75% of nuclei were stained positively in a region exceeding 12 cells. A positive score of Ki67 was assigned if there was nuclear staining in a discrete focus greater than twice that of adjacent epithelium. A positive score for atypia required at least moderate mucosal epithelial proliferation, defined as including cellular crowding, stratification, loss of nuclear polarity, and at least moderate nuclear atypia in a discrete focus.17, 18, 19 All slides scored as positive by immunohistochemistry and/or histological examinations were reviewed by a second pathologist (EP). Final positive scores were determined after final review by both pathologists.

Statistical analysis included assessment of the association of each biomarker (atypia, p53 overexpression, Ki67 overexpression) with BRCA mutation status and with age. In addition to the individual biomarkers, the analysis included assessment of diagnoses, including p53 signature and tubal intraepithelial carcinoma, using Fisher's exact test.

Results

Case Material

Bilateral fallopian tubes were analyzed from a total of 240 women, including 103 BRCA1 mutation carriers, 73 BRCA2 mutation carriers, and 64 control patients. Median age at the time of surgery was 46 years for the BRCA mutation group and 48.5 years for the control group (Table 1). Final diagnoses for the control group included benign ovarian tumors (n=18), uterine leiomyoma (n=16), squamous carcinoma, adenocarcinoma or squamous intraepithelial lesion of the cervix (n=11), uterine adenomyosis or pelvic endometriosis (n=9), no diagnostic histopathology (n=7), endometrial adenocarcinoma (n=3).

Frequency of p53 Overexpression

Overall, 21% (n=51) of the 240 cases, including 16 controls and 35 BRCA cases, showed at least one focus of p53 overexpression, as detected by immunohistochemistry (Table 2). These included 31 cases in which the p53 overexpression was not associated with significant histological atypia or with Ki67 overexpression, and were therefore diagnosed as ‘p53 signatures’ using the terminology proposed by Crum et al. p53 signatures were found in 19 of the BRCA cases (10%) and in 11 control cases (17%). In all cases, the p53 signature was identified in the fimbria or in the distal tube just proximal to the fimbria. Generally these lesions were very small, with the majority composed of less than 50 cells. They were multifocal in 31% of cases, with up to three p53 signatures seen in both BRCA and control cases (Figure 1).

In 17 cases (14 BRCA, 3 control), p53 overexpression was associated with histological atypia and/or increased Ki67 expression. A total of, 13 of these (11 BRCA, 2 control) were diagnosed as tubal intraepithelial carcinoma, with histological features of carcinoma including stratification, increased nuclear size, nuclear pleomorphism, loss of polarity, and prominent nucleoli. In addition to p53 overexpression, Ki67 staining was also increased, making these lesions ‘triple positives’ (Figure 2). In another four p53-positive lesions (two BRCA, two control), atypia and stratification were present, but there was only a slight increase in Ki67 staining so that histological criteria for a diagnosis of tubal intraepithelial carcinoma were not fulfilled.

Frequency of Tubal Intraepithelial Carcinoma

Tubal intraepithelial carcinoma was diagnosed in 17 cases (15 BRCA, 2 control). In 13 cases (76%), p53 was overexpressed, but in four cases, all BRCA mutation carriers, the combination of histological features, and Ki67 staining were sufficient for a diagnosis of tubal intraepithelial carcinoma, in the absence of p53 overexpression (Figure 3). Tubal intraepithelial carcinoma, with or without p53 overexpression, was detected in 8% of BRCA mutation carriers compared with 3% of controls, a difference which was not significant using Fisher's exact test (P-value=0.25).

Tubal intraepithelial carcinoma was multifocal in three cases (18%), and associated with other lesions, usually p53 overexpression without atypia or increased Ki67 expression, in another five cases (29%). All tubal intraepithelial carcinoma were located in the fimbria or in the distal tube, with the exception of one case, found in the mid section of the isthmus.

The p53-positive tubal intraepithelial carcinoma was shown in two control cases. In neither case was there a known family or medical history that would put them at increased risk of ovarian/tubal carcinoma. One patient had surgery for adenocarcinoma of the cervix, which had morphology unlike the tubal carcinoma. The other had a benign serous cystadenoma of the contralateral ovary.

Frequency of Other Lesions

In both the BRCA and control groups, there were lesions difficult to classify. In four cases (two BRCA, two controls), histological atypia and p53 overexpression were present with no or minimal increased Ki67. These may represent a lesion transitional between the p53 signature and tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. In another three cases, there was focal increased Ki67 expression, without atypia or p53 overexpression, indicative of focal hyperplasia.

Discussion

This study included women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline mutations undergoing prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy at our center, with thorough histological examination of all portions of the fallopian tubes, and is the largest series documenting abnormalities of the fallopian tube epithelium in mutation carriers reported to date. We have identified tubal intraepithelial carcinomas in 8% of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, with 8% in BRCA1 and 10% in BRCA2 carriers. Similar to early and occult carcinomas arising in this high-risk population, tubal intraepithelial carcinoma has a marked predilection for the fimbrial and distal tubal epithelium, with only one tubal intraepithelial carcinoma found in the midportion of the tube and none found in the proximal portion. This finding has clinical implications. Whether hysterectomy should be included in prophylactic surgery for high-risk women is still controversial, but it seems that hysterectomy will not contribute to the risk reduction of adnexal serous carcinoma. Hysterectomy may be considered in women treated with tamoxifen, to eliminate the risk of tamoxifen-associated uterine malignancies, and other benefits include the option of hormone replacement without progesterone.22 Some reports23, 24 suggest that mutation carriers may be at increased risk of uterine serous carcinoma, although two independent studies failed to show an increased risk in BRCA mutation carriers.25, 26, 27

Tubal intraepithelial carcinoma is not confined to BRCA mutation carriers. Kindelberger et al21 documented tubal intraepithelial carcinoma in a significant percentage of high-grade serous carcinomas unselected for family history or BRCA mutation status, coexisting with carcinomas designated as of tubal, ovarian, or peritoneal origin, and proposed that tubal intraepithelial carcinoma may be the source of serous carcinoma in many of these tumors. An unexpected finding in our study was the identification of two intraepithelial carcinomas in the control group. These patients were assessed as being at low risk of carcinoma based on the family history, and did not undergo testing for germline mutations. However, this group should not be considered as representative of the general population, because all had surgery for gynecological indications. In addition, we do not believe that the findings should be interpreted as indicating an incidence of tubal intraepithelial carcinoma higher than that anticipated in a group of patients not known to be at increased risk. It should be noted, however, that there have been no other publications comprehensively examining a similar series of fallopian tubes, and the prevalence and the significance of these lesions in the general population is unknown.

The tumor suppressor gene, TP53, is mutated in 80% of BRCA-mutation-linked ovarian/tubal carcinomas, and p53 mutations have been identified in early stage and in situ serous carcinomas, indicating a key role for altered p53 function in serous carcinogenesis.28, 29 Missence mutations, the mutation type most commonly found in serous carcinoma, increases stability of the altered protein leading to the nuclear accumulation detected by immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemistry will be negative, however, if the p53 mutation, such as an insertion, deletion, or premature stop codon, leads to cessation of p53 production.30 Lee et al have documented p53 mutations in 12 out of 12 cases of tubal intraepithelial carcinoma, all of which were defined in part by p53 overexpression. High-grade serous carcinomas frequently overexpress p53, and there is no difference in the frequency of p53 staining between hereditary and sporadic serous cancers.31, 32 It would not be expected then that all serous cancer precursors will necessarily overexpress p53, and indeed in our series, overexpression of p53 was identified in 79% of tubal intraepithelial carcinoma lesions, approximating the frequency of p53 overexpression in high-grade serous cancers. Therefore, it is important to note that positive p53 staining by immunohistochemistry is not required to make a diagnosis of tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Tubal intraepithelial carcinoma has in the past been defined as a lesion characterized by replacement of normal tubal epithelium by malignant cells, with increased nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, nuclear pleomorphism, disorganized growth, and increased proliferation. Jarboe et al20 recently added two additional criteria to the definition, including the absence of ciliated cells and the presence of prominent nucleoli. This definition may be too restrictive, and will likely be revised as additional studies further our understanding of these intramucosal malignancies.

Crum et al have shown that tubal p53 signatures occur with similar frequency in the ‘low cancer risk’ control patients and ‘high cancer risk’ BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Our study has confirmed this finding, although in our series, the frequency was lower than that reported by Lee et al.4 The lower frequency of p53 signatures may be in part because of the different protocols used in histological processing. The cases in our series were from archival cases over a 9-year period, and although the tubes in all cases were serially sectioned and embedded in toto for histological examination, we have only recently adopted the SEE-FIM protocol, which likely increases the surface area of tubal epithelium examined histologically, and may lead to an increased detection of small lesions.

The biological and clinical significance of the more prevalent lesion, the p53 signature, is uncertain. Crum et al have shown that at least some of these lesions have p53 mutations, and have suggested that they are associated with oxidant-induced damage resulting from ovulation.4 This is an attractive theory, and is consistent with epidemiological data that indicates increased lifetime ovulations to be a major risk factor of ovarian carcinoma.

In conclusion, we have shown that p53 signatures are frequent in the distal ends of fallopian tubes of women undergoing adnexectomy, and that they occur with the same frequency in women at high and low genetic risk for tubal/ovarian serous carcinoma. In contrast, tubal intraepithelial carcinoma, a lesion widely accepted to be a cancer precursor, is identified more frequently in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. We have shown that tubal intraepithelial carcinoma usually, but not always, overexpress p53 protein by immunohistochemistry, and therefore believe that, although immunohistochemistry is very useful in highlighting the tubal precursor lesions, a negative p53 stain does not exclude the diagnosis of tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. This study contributes to the growing literature identifying cancer precursor candidates in the fallopian tube epithelium, with lesions identified not only in BRCA mutation carriers but also in women not known to be at high risk of ovarian/tubal/peritoneal carcinoma. Further morphological and molecular characterization of these lesions is of great importance to the further understanding of serous oncogenesis, with implications for preventative strategies, ovarian cancer screening, and identification of women at risk who may be eligible for preventative surgical techniques.

References

Hogg R, Friedlander M . Biology of epithelial ovarian cancer: implications for screening women at high genetic risk. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1315–1327.

Shaw P, Rouzbahman M, Murphy J, et al. Mucosal epithelial proliferation and p53 overexpression are frequent in women with BRCA mutations (Abstract). Mod Pathol 2004;17 (Supp 1):214A.

Crum CP, Drapkin R, Kindelberger D, et al. Lessons from BRCA: the tubal fimbria emerges as an origin for pelvic serous cancer. Clin Med Res 2007;5:35–44.

Lee Y, Miron A, Drapkin R, et al. A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tube. J Pathol 2007;211:26–35.

Medeiros F, Muto MG, Lee Y, et al. The tubal fimbria is a preferred site for early adenocarcinoma in women with familial ovarian cancer syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:230–236.

Auersperg N, Wong AS, Choi KC, et al. Ovarian surface epithelium: biology, endocrinology, and pathology. Endocr Rev 2001;22:255–288.

Wong AS, Auersperg N . Ovarian surface epithelium: family history and early events in ovarian cancer. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2003;1:70.

Salazar H, Godwin AK, Daly MB, et al. Microscopic benign and invasive malignant neoplasms and a cancer-prone phenotype in prophylactic oophorectomies. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996;88:1810–1820.

Stratton JF, Buckley CH, Lowe D, et al. Comparison of prophylactic oophorectomy specimens from carriers and noncarriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation. United Kingdom Coordinating Committee on Cancer Research (UKCCCR) Familial Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:626–628.

Barakat RR, Federici MG, Saigo PE, et al. Absence of premalignant histologic, molecular, or cell biologic alterations in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens from BRCA1 heterozygotes. Cancer 2000;89:383–390.

Sherman ME, Lee JS, Burks RT, et al. Histopathologic features of ovaries at increased risk for carcinoma. A case–control analysis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1999;18:151–157.

Paley PJ, Swisher EM, Garcia RL, et al. Occult cancer of the fallopian tube in BRCA-1 germline mutation carriers at prophylactic oophorectomy: a case for recommending hysterectomy at surgical prophylaxis. Gynecol Oncol 2001;80:176–180.

Leeper K, Garcia R, Swisher E, et al. Pathologic findings in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens in high-risk women. Gynecol Oncol 2002;87:52–56.

Finch A, Shaw P, Rosen B, et al. Clinical and pathologic findings of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies in 159 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Gynecol Oncol 2006;100:58–64.

Callahan MJ, Crum CP, Medeiros F, et al. Primary fallopian tube malignancies in BRCA-positive women undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer risk reduction. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3985–3990.

Yanai-Inbar I, Siriaunkgul S, Silverberg SG . Mucosal epithelial proliferation of the fallopian tube: a particular association with ovarian serous tumor of low malignant potential? Int J Gynecol Pathol 1995;14:107–113.

Piek JM, van Diest PJ, Zweemer RP, et al. Dysplastic changes in prophylactically removed fallopian tubes of women predisposed to developing ovarian cancer. J Pathol 2001;195:451–456.

Carcangiu ML, Radice P, Manoukian S, et al. Atypical epithelial proliferation in fallopian tubes in prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy specimens from BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutation carriers. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2004;23:35–40.

Yanai-Inbar I, Silverberg SG . Mucosal epithelial proliferation of the fallopian tube: prevalence, clinical associations, and optimal strategy for histopathologic assessment. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2000;19:139–144.

Jarboe E, Folkins A, Nucci MR, et al. Serous carcinogenesis in the fallopian tube: a descriptive classification. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2008;27:1–9.

Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: evidence for a causal relationship. Am J of Surg Pathol 2007;31:161–169.

Kauff ND, Barakat RR . Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in patients with germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:2921–2927.

Hornreich G, Beller U, Lavie O, et al. Is uterine serous papillary carcinoma a BRCA1-related disease? Case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 1999;75:300–304.

Lavie O, Hornreich G, Ben-Arie A, et al. BRCA germline mutations in Jewish women with uterine serous papillary carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2004;92:521–524.

Levine DA, Lin O, Barakat RR, et al. Risk of endometrial carcinoma associated with BRCA mutation. Gynecol Oncol 2001;80:395–398.

Beiner ME, Finch A, Rosen B, et al. The risk of endometrial cancer in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. A prospective study. Gynecol Oncol 2007;104:7–10.

Goshen R, Chu W, Elit L, et al. Is uterine papillary serous adenocarcinoma a manifestation of the hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndrome? Gynecol Oncol 2000;79:477–481.

Salani R, Kurman RJ, Giuntoli R, et al. Assessment of TP53 mutation using purified tissue samples of ovarian serous carcinomas reveals a higher mutation rate than previously reported and does not correlate with drug resistance. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2008;18:487–491.

Rhei E, Bogomolniy F, Federici MG, et al. Molecular genetic characterization of BRCA1- and BRCA2-linked hereditary ovarian cancers. Cancer Res 1998;58:3193–3196.

Sjogren S, Inganas M, Norberg T, et al. The p53 gene in breast cancer: prognostic value of complementary DNA sequencing versus immunohistochemistry. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996;88:173–182.

Zweemer R, Shaw P, Verheijen R, et al. Accumulation of p53 protein is frequent in ovarian cancers associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations. J Clin Pathol 1999;52:372.

Aghmesheh M, Nesland JM, Kaern J, et al. No differences in p53 mutation frequencies between BRCA1-associated and sporadic ovarian cancers. Gynecol Oncol 2004;95:430–436.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Canary Foundation. We would like to thank Merna Cardoso for her dedicated administrative support, Kelvin So and his colleagues in the University Health Network Pathology Research Program for the technical support, and Dr Joan Murphy and Barry Rosen of the University Health Network Familial Ovarian Cancer Clinic.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shaw, P., Rouzbahman, M., Pizer, E. et al. Candidate serous cancer precursors in fallopian tube epithelium of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Mod Pathol 22, 1133–1138 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.89

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.89

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Recommendations for diagnosing STIC: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Virchows Archiv (2022)

-

Ovarian BDNF promotes survival, migration, and attachment of tumor precursors originated from p53 mutant fallopian tube epithelial cells

Oncogenesis (2020)

-

PAX2 function, regulation and targeting in fallopian tube-derived high-grade serous ovarian cancer

Oncogene (2017)