Abstract

Colonic sessile serrated adenoma, in contrast to hyperplastic polyp, is thought to be related to sporadic colorectal cancers with high microsatellite instability. However, the morphological distinction between these entities is difficult and subject to observer and sampling variation. Therefore, we elected to investigate the expression of gastric mucin MUC6 as a potential marker to separate the two in the hope of finding an objective and reproducible adjunct to morphological diagnosis. Endoscopic biopsies of colonic polyps with serrated architecture, but without cytological dysplasia were studied and categorized as sessile serrated adenoma or hyperplastic polyp, using previously published morphological criteria. Smaller groups of serrated polyps with cytological dysplasia (traditional serrated adenomas, filiform serrated adenomas and sessile serrated adenomas with cytological dysplasia) were also included. In total, 94 polyps were immunohistochemically stained with antibodies to MUC6 and to MLH-1. MUC6 was found to have 100% specificity in distinguishing sessile serrated adenoma (N=26; positive staining) from hyperplastic polyp (N=48; negative staining). Traditional serrated adenomas and filiform serrated adenomas were also negative for MUC6. Sessile serrated adenomas with cytological dysplasia were found to lose expression of MLH-1 in dysplastic areas, while retaining MUC6 expression. Neither anatomic location in the right or left colon nor polyp size appears to account for the differences in MUC6 expression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Colorectal serrated polyp is a broad category that includes several types of newly described polyps. A current classification and terminology scheme is summarized in Table 1, and was used in this study. Sessile serrated adenoma is one recently described entity that, although lacking in conventional adenomatous cytological dysplasia, is thought to be related to colorectal adenocarcinoma by the so-called ‘serrated pathway’ of colorectal neoplasia.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 This pathway results in invasive adenocarcinomas that are frequently microsatellite unstable (MSI-high).3, 6 Sessile serrated adenomas occur most commonly on the right side of the colon, but can be found throughout.4, 7

The increasing acceptance of sessile serrated adenoma as a diagnostic entity has undermined the traditional notion that colonic polyps could be broadly divided into traditional adenomatous polyps, exhibiting characteristic cytological dysplasia and imparting a higher risk of progression to invasive adenocarcinoma, and ‘hyperplastic polyps’, lacking cytological dysplasia and thought to be of essentially no risk for development of carcinoma. Whether such a ‘safe’ category actually exists—especially in the right colon—is a matter of current debate and study.8

According to Snover et al4, sessile serrated adenomas are those serrated polyps with evidence of abnormal proliferation, including basal crypt branching, dilation, serration and horizontal basal crypt orientation, creating T- or L- shaped crypts.4 These features have been termed architectural dysplasia in the literature, and are evaluated in combination with an assessment of traditional cytological dysplasia, which is absent in sessile serrated adenomas. In contrast, hyperplastic polyps do not exhibit such features of abnormal proliferation. Areas of cytological dysplasia or invasive carcinoma arising in sessile serrated adenomas have been well documented in the literature.9 Whether cytological dysplasia can also arise in a typical hyperplastic polyp has never been closely examined.

The concept of cancer-associated serrated polyps is still evolving, and such polyps are currently defined and diagnosed predominantly based on morphological features. Several new terminologies have been added to the list since 1990 when Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser10 first introduced the entity of serrated adenoma. They described serrated adenoma as a type of colonic polyp with serrated crypts lined by epithelium with traditional cytological dysplasia. Whether serrated adenoma is related to hyperplastic polyp or to more typical adenomatous polyps is not completely clear. Since its original description, serrated adenoma has been further classified into non-filiform traditional serrated adenoma and filiform serrated adenoma.11 Traditional serrated adenomas can be found throughout the colon, whereas filiform serrated adenomas are located exclusively in the left colon, especially in the rectum and sigmoid. Those polyps that have morphological features of sessile serrated adenomas described above, in combination with discrete areas of traditional adenomatous dysplasia, can be termed ‘sessile serrated adenoma with dysplasia’.9

The morphological distinction between sessile serrated adenoma and hyperplastic polyp is clinically important because of their apparently different cancer risk. Several factors affect the accurate diagnosis of sessile serrated adenomas and hyperplastic polyps. Interobserver variability is a major issue. In a recent report, the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma was found to have low interobserver agreement among gastrointestinal pathologists.12 Given this finding, pathologists without extensive gastrointestinal pathology training may be expected to encounter significant difficulty and frustration in making the diagnosis during daily practice. As the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma relies so heavily on the morphology of basal crypts, biopsy size and orientation during processing can also have a great impact on the availability of the characteristic features.

Several molecular characteristics of the serrated neoplasia pathway have been explored for potential usefulness in distinguishing sessile serrated adenoma from hyperplastic polyp.13, 14, 15, 16 For example, BRAF mutation is common in sessile serrated adenoma and the microvesicular variant of hyperplastic polyp, whereas KRAS mutations are significantly associated with the goblet cell variant of hyperplastic polyp. However, routine assessment of earlier genetic events such as BRAF and KRAS mutations can be costly and impractical in a typical surgical pathology laboratory, and the distinction may not be completely specific. On the other hand, loss of MLH-1, a hallmark of MSI-high cancer, is not a sensitive marker for prediction of progression of sessile serrated adenomas because its loss occurs late in the serrated pathway. Therefore, morphological features remain the gold standard for diagnosis and the elucidation of a sensitive and specific adjunct, preferably an immunohistochemical stain, could aid significantly in the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma in the busy daily practice of pathologists.

Mucin (MUC) gene products are high-molecular-weight glycoproteins that are commonly expressed in epithelial cells. Currently, about 20 MUC genes (designated MUC1 to MUC19 with a handful of subcategories such as MUC5AC and MUC5B) have been identified and/or sequenced. Their expression is relatively specific to certain organs and types of tissue. For example, MUC2 is a goblet cell-type mucin predominantly expressed in the colon and small bowel. On the other hand, MUC5AC and MUC6 are two gastric type mucins that are expressed in the surface foveolar epithelium and deep antral/pyloric glands, respectively.17, 18, 19

Aberrant and bidirectional gastric differentiations of foveolar mucin (MUC5AC) and pyloric mucin (MUC6) have been reported in colonic serrated adenomas and hyperplastic polyps.20 In that article, the authors indicated that MUC5AC-positive cells are typically located throughout the entire length of the crypts, whereas cells expressing MUC6 are present only in the basal crypts. However, most of the cases of ‘serrated adenoma’ in that report could be better classified as traditional serrated adenoma than sessile serrated adenoma, because 11 out of 20 were pedunculated rather than sessile. Additionally, some of the polyps classified by the authors as hyperplastic polyps and illustrated in their photomicrographs may be better classified as sessile serrated adenomas by the current criteria, because of the presence of serration and dilation in the basal crypts.

Given the prior reports regarding expression of MUC and the current difficulties in the morphological classification of serrated polyps, we investigated the expression of MUC6 as a potential adjunct to morphological diagnosis in sessile serrated adenomas with and without dysplasia, as compared to hyperplastic polyps, filiform serrated adenomas and traditional serrated adenomas. Because of the connection between sessile serrated adenoma and MSI-high carcinoma, we also investigated the expression of MLH-1 in these polyps.

Materials and methods

Eighty colonic polyps with serrated architecture but without traditional cytological dysplasia, biopsied from sites throughout the colon, were collected during clinical service in the Department of Pathology at the University of Pittsburgh. In addition, 20 polyps with a combination of serrated architecture and cytological dysplasia were also collected. For the latter group of polyps, the criterion of cytological dysplasia was based on the presence of pseudostratified, hyperchromatic, elongated or ‘pencil-like’ nuclei (Figure 4a, inset). Such nuclear features were absent in the 80 serrated polyps without cytological dysplasia. Because we chose to limit the scope of our investigation to the comparison of MUC6 expression in sessile serrated adenoma and hyperplastic polyp, and its evaluation as an adjunct to the gold standard of morphological diagnosis, no effort was made to include a consecutive sampling of all serrated polyps diagnosed within a certain timeframe. However, to limit the investigation to sporadically acquired serrated polyps, those polyps found in association with inflammatory bowel disease were excluded, as were the cases that met the diagnostic criteria for ‘hyperplastic polyposis’ as set forth by the World Health Organization.21 None of the patients identified for study had more than five such polyps. All cases were collected during a span of 4 years (2003–2007).

For each polyp, biopsy site was categorized as either right-sided (sites proximal to the splenic flexure) or left-sided (distal to the splenic flexure). All of the biopsies contained at least a portion of well-oriented, full-thickness mucosa, ensuring that adequate architectural characteristics were visible. Many biopsies also contained unremarkable, flat mucosa adjacent to the polyps and/or in separately sampled pieces received with the biopsy. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections from each case were stained with immunohistochemical antibodies to MUC6 and MLH-1 according to the vendor's instructions and previously published methods22 (Table 2).

Without prior knowledge of their clinical features and immunohistochemical staining patterns, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections were independently reviewed by two of the authors (SRO and SFK), both fellowship-trained gastrointestinal pathologists. For the polyps without cytological dysplasia, a diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma or hyperplastic polyp was made based on previously published morphological criteria.4 Briefly, the polyps were assessed for the presence of morphological features of abnormal proliferation including basal crypt dilation, branching, serration and horizontal orientation, in combination with abundant goblet cell or gastric-type mucin production in the basal crypts (ie, the ‘proliferation zone’ of normal mucosa and hyperplastic polyp) (Figure 1a–c). Those polyps with at least two such features were classified as sessile serrated adenomas and those without as hyperplastic polyps (Figure 2a and b). The polyps found to contain cytological dysplasia were classified as traditional serrated adenoma,23 filiform serrated adenoma11 or sessile serrated adenoma with dysplasia.9 The diagnosis of traditional serrated adenoma included polyps having both serrated profile and adenomatous epithelium within the same crypts, along with characteristic eosinophilic apical cytoplasm (Figure 4a). Polyps diagnosed as filiform serrated adenoma had a similar appearance to the traditional serrated adenomas, but with characteristic elongated, filiform architecture (Figure 4b). In contrast, sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia included polyps that otherwise would have been categorized morphologically as sessile serrated adenoma, but which also contained a discrete collection of crypts lined by epithelium with definite cytological dysplasia as described above (Figure 3a and b). For all of the cytologically dysplastic polyps, the dysplasia was graded by both pathologists as low- or high-grade based on published criteria.9, 24 A diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia required a significant degree of nuclear pleomorphism and pseudostratification, as well as architectural changes such as ‘crypt-within-crypt’ formation, cribriform architecture and ‘back-to-back’ crypts. The presence of components morphologically consistent with sessile serrated adenoma and/or hyperplastic polyp in these polyps was also noted.

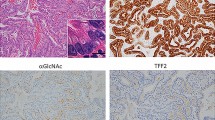

Sessile serrated adenoma. Sessile serrated adenomas are characterized by horizontal orientation, branching, dilation and mucus production in the basal crypts (a–c). The basal crypts express MUC6, predominantly in straight or branched crypts (d), and also in some dilated and horizontally-oriented crypts (e). Inset in panel e depicts the pattern of staining in the epithelial cells. (f) MLH-1 expression is intact. All × 100 original magnification.

Sessile serrated adenoma with dysplasia. Sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia are characterized by crypts with the unique morphology of sessile serrated adenoma, in combination with crypts lined by epithelium with conventional cytological dysplasia (a and b; the majority of the cytologically dysplastic crypts are in the left-most halves of each panel). These polyps also express MUC6 (c), including areas of cytological dysplasia. In areas of high-grade dysplasia (arrows and inset) and submucosally-invasive adenocarcinoma (not shown, but present in the polyp pictured), MLH-1 expression is lost (d). All × 100 original magnification.

Where there was initial agreement on the diagnosis by both pathologists, the polyp was included without further review. In cases with an initially discordant diagnosis, the polyps were reviewed by the two pathologists together and discussed in an attempt to reach consensus. In this reexamination, more subtle examples of the aforementioned features of sessile serrated adenoma were identified and debated. Because of the distinctive appearance of extensively dilated and/or horizontally oriented basal crypts, special attention was given to these features during the consensus review. If this process resulted in the confirmation of at least two relevant architectural attributes, the polyp was classified as sessile serrated adenoma. Cases where a concordant diagnosis could not be reached were excluded. Initially, 10 polyps were identified that did not have a consensus diagnosis. After further review, consensus was reached for four of these (three sessile serrated adenomas and one hyperplastic polyp). This resulted in the exclusion of six serrated polyps without cytological dysplasia, for a total of 74 such polyps included in the study. All six of the excluded polyps had areas of so-called ‘inverted growth’ (displacement of mucosa beneath the muscularis mucosae), which we found made them difficult to subclassify. There was full concordance on the diagnoses of traditional serrated adenoma, filiform serrated adenoma and sessile serrated adenoma with dysplasia.

Once the diagnosis for each included polyp was established, staining for MUC6 and MLH-1 was evaluated. For both, the overall presence or absence of staining was recorded, as was the pattern of staining. Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate the significance of different staining patterns among the polyps. A paired t-test was utilized to evaluate the difference in mean size of sessile serrated adenomas and hyperplastic polyps, as well as the mean patient ages in the four polyp categories.

Results

Table 3 summarizes the clinicopathological features and results. Patient age did not differ significantly among the diagnostic categories apart from sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia, where the patients were significantly older (P=0.01). Of the 74 serrated polyps without cytological dysplasia, 26 were classified as sessile serrated adenoma and 48 as hyperplastic polyp. The remaining 20 polyps included 7 traditional serrated adenomas, 6 filiform serrated adenomas and 7 sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia. Polyp size ranged from 2 to 18 mm. Sessile serrated adenomas (mean 8 mm) were significantly larger than hyperplastic polyps (mean 4.75 mm; P=0.0005). By anatomic location, 21/26 (81%) sessile serrated adenomas were taken from the right colon, whereas 47/48 (98%) hyperplastic polyps were located in the left colon (P<0.0001). All of the sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia were located in the right colon and all of the traditional/filiform serrated adenomas in the left colon.

All 26 sessile serrated adenomas had MUC6 staining in at least some of the basal crypts (Figure 1d and e). Most MUC6-positive cells in the sessile serrated adenomas were located in regular, straight basal crypts (Figure 1d) rather than in crypts with characteristic architectural features such as dilation, branching or horizontal orientation. However, scattered basally dilated and horizontal crypts were positive (Figure 1e). Crypts with basal serration and/or branching were only rarely positive for MUC6. None of the hyperplastic polyps was positive for MUC6 (P<0.0001) (Figure 2c). Where present, flat (non-polyp) mucosa included in the biopsies was also completely negative for MUC6 staining, regardless of anatomical location.

All seven sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia contained areas of morphologically typical sessile serrated adenoma (Figure 3a and b). Five had areas of high-grade dysplasia and two of these five had areas of adenocarcinoma invasive into the submucosa. The remaining two sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia had only low-grade dysplasia. All of the traditional and filiform serrated adenomas had low-grade dysplasia and 8/13 (62%) contained non-cytologically dysplastic areas morphology typical of hyperplastic polyp (Figure 4a and b). The seven sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia expressed MUC6 in non-dysplastic areas, and retained varying degrees of staining in areas of cytological dysplasia (Figure 3c). Specifically, areas of high-grade dysplasia were MUC6-positive in 2/5 polyps, invasive carcinoma in 2/2 polyps and one of the two sessile serrated adenomas with only low-grade dysplasia had foci of positivity within the dysplastic crypts. The traditional and filiform serrated adenomas were all negative for MUC6 (Figure 4d).

Expression of MLH-1 was preserved in all but five polyps in the study, all sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia that contained high-grade dysplasia and/or adenocarcinoma (P<0.0001) (Figure 3d). In these five polyps, MLH-1 staining was lost in the areas with high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma, which still retained MUC6 staining (Figure 3c). MLH-1 was positive in the non-dysplastic areas in all of the polyps, as well as in areas of low-grade dysplasia. All flat (non-polyp) mucosa included in the biopsies also retained MLH-1 expression.

Discussion

The concordance rate (74/80; 93%) for the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma and hyperplastic polyp in our series was higher than that previously reported by Glatz et al12. We attribute this to a combination of the gastrointestinal subspecialty training of the two authors making the diagnoses (a point similarly made by Glatz et al) as well as the opportunity to discuss initially discordant diagnoses in an attempt to reach a consensus. Although not a consecutive sample of all serrated polyps, the patient's demographic characteristics (Table 3) were similar to those previously seen in the literature.4, 7 Thus, most sessile serrated adenomas in our series were found in the right colon of older women, whereas the majority of hyperplastic polyps came from the left colon with no gender preference. Given the finding of only one right-sided hyperplastic polyp, our data also support the concept that hyperplastic polyps rarely arise, or at least are rarely sampled, in the right colon. In addition, our results show several important morphological and immunohistological features that have not been previously addressed in the literature.

Aberrant and ectopic gastric-type mucin has been previously reported in colonic hyperplastic polyps. In fact, hyperplastic polyp is also known as ‘metaplastic polyp’ because of the presence of gastric metaplasia.25, 26 However, the mechanism of MUC6 expression in serrated polyps is unknown. Ectopic expression of MUC6 is commonly found in gastrointestinal diseases associated with regenerative mucosa secondary to ulcers and inflammation. For example, MUC6 is expressed in pseudopyloric metaplasia found in inflammatory bowel disease.27, 28 Similarly, pseudopyloric metaplasia seen ‘replacing’ lost glands in fundic gastritis also expresses MUC6. Researchers have found that MUC6 mucin is upregulated by NFκB, a nuclear transcription factor that is also activated in inflammatory and neoplastic cells.29 This finding seems compatible with the theory that metaplastic/hyperplastic polyps develop in response to inflammation;25 however, the precise reason for selective expression of MUC6 in the cancer-associated sessile serrated adenomas, but not hyperplastic polyps is still unclear.

The fact that not all basal crypts with the characteristic morphology found in sessile serrated adenoma were MUC6-positive is also intriguing. It suggests that some of these ‘morphologically diagnostic’ basal crypts may not contain the ‘stem cells’ that give rise to sessile serrated adenoma. In fact, Batts30 found that inverted growth of surface epithelium can be seen in sessile serrated adenoma, which could explain the lack of MUC6 staining in a variable number of basal crypts. Our findings also indicate that many MUC6-negative serrated basal crypts in sessile serrated adenoma express MUC5AC, another gastric-type mucin usually only seen in surface epithelium (unpublished personal data).

The frequent association of MUC6 positivity and right-sided serrated polyps raises the issue of whether MUC6 is in fact simply a marker of right-sided polyps. Indeed, there is accumulating evidence suggesting that the right and left colon may be considered as two distinct ‘organs’ with different embryology, biochemical metabolism and carcinogenesis.31, 32 Although it does not appear simply to be a marker of the right colon itself (as it was negative in flat mucosa regardless of site), it is difficult to address the possibility that MUC6 may highlight right colon polyps regardless of their pathogenesis, because of the distinct segregation of sessile serrated adenomas and hyperplastic polyps in the right and left colon, respectively. However, our series did include five left colonic sessile serrated adenomas that were MUC6-positive, and one right colonic hyperplastic polyp that was MUC6-negative. Therefore, it does not appear that the location alone can be implicated in this immunohistochemical phenomenon. Larger series of sessile serrated adenomas from the left colon and hyperplastic polyps from the right colon (if such an entity exists in any significant number) could help to settle this issue.

Our finding of loss of MLH-1 expression in those polyps with morphological features of sessile serrated adenoma in combination with discrete areas of cytological (adenomatous) dysplasia fits well with the evolving concept of a ‘serrated’ neoplasia pathway that includes sessile serrated adenoma as a precursor lesion. Thus, it appears that MLH-1 loss is a late event in the pathway, correlated with the acquisition of cytological dysplasia, whereas ectopic expression of MUC6 seems to be a much earlier event, associated with the acquisition or expression of characteristic architectural features of basal crypts, upon which the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma is currently based. Furthermore, the finding of a combination of lost MLH-1 expression and positive MUC6 staining in the areas of sessile serrated adenomas with high-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma suggests that MUC6 could even play a role in the malignant transformation of these polyps.

The sessile serrated adenomas in our series were significantly larger than the hyperplastic polyps. Based on this finding, it is possible that MUC6 staining could be related to polyp size rather than to morphological or pathophysiological polyp subtype. However, both the presence of MUC6 expression in at least some architecturally characteristic basal crypts associated with sessile serrated adenoma, as well as the expression of MUC6 within cytologically dysplastic areas of sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia together with a loss of MLH-1 argue against this explanation. In addition, MUC6 staining was evident even in the smallest of the sessile serrated adenomas in our series (from 3 to 5 mm in size) and was notably absent in the subset of hyperplastic polyps of similar size.

Although the sessile serrated adenomas and hyperplastic polyps in our study had very distinct anatomical locations and MUC6 expression, the parallel comparison between sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia and the traditional/filiform serrated adenomas is also interesting. All of our sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia were located in the right colon, whereas all of our traditional and filiform serrated adenomas were located in the left colon. Although traditional serrated adenoma has been previously demonstrated to occur throughout the colon, we believe that the relatively high number of filiform serrated adenomas in our ‘cytologically dysplastic serrated polyp’ group accounts for the skew toward the left-sided location, as these polyps have been shown to occur only in the left colon. Sessile serrated adenoma with dysplasia can be considered the ‘advanced’ stage of sessile serrated adenoma because it contains areas morphologically typical for sessile serrated adenoma and occurs more often in the right colon, but loses expression of MLH-1 in the dysplastic areas. Interestingly, most serrated adenomas with cytological dysplasia in our study, particularly the filiform variant, also contained areas morphologically typical for hyperplastic polyp and all were located in the left colon. These findings raise the possibility that filiform serrated adenoma may be the ‘advanced’ form of hyperplastic polyp.

The distinction between sessile serrated adenoma with dysplasia and traditional/filiform serrated adenoma has not been addressed in the literature. Based on the authors' experience in daily practice, the morphological differentiation, especially between sessile serrated adenoma with dysplasia and traditional serrated adenoma, may be difficult, particularly when the characteristic crypt architecture of sessile serrated adenoma has been largely replaced by the dysplastic component, or when the sessile serrated adenoma component has not been extensively sampled. In this situation, MUC6 could be a useful marker in making this diagnostic distinction.

Our findings substantiate the need for full-thickness mucosal biopsies in the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma. Visible basal crypts are vital, both when using morphology alone and when adding MUC6 staining. If the sessile serrated adenoma is removed in numerous small pieces, the basal crypts are less likely to be sampled. Therefore, we recommend that sessile polyps in the right colon be removed by the injection-assisted method of instilling saline beneath the polyp. This method has been described in the literature,33 and should result in more diagnostic tissue including the basal crypts being available for diagnosis. Of course, many sessile serrated adenomas may simply be too large to be amenable to this method, but every effort should be made to ensure the presence of basal mucosa in the biopsy or polypectomy.

Cancer-associated serrated polyps without traditional cytological dysplasia are an increasingly accepted and recognized diagnostic category in pathology practice. Most diagnostic criteria to date have been based on morphological clues to abnormal proliferation or ‘architectural dysplasia’, and are, by nature, qualitative rather than quantitative. Our study illustrates the utility of immunohistochemical staining for MUC6 as an adjunct to morphological assessment in the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma. Although MUC6 is clearly ‘morphology-associated’, there is also evidence to suggest that it may be a ‘pathway-associated’ marker in colorectal cancer. In addition to its association with loss of MLH-1 expression in this and one other study,9 other preliminary studies show that MUC6 is more commonly positive in microsatellite-unstable than in microsatellite-stable colon cancer34 and that it is largely negative in ‘traditional’ adenomatous polyps (unpublished personal data). Thus, it is our hope that the findings will provide both a diagnostic aid to the practicing pathologist, and a window into the pathogenesis of these unique colonic polyps.

References

Goldstein NS, Bhanot P, Odish E, et al. Hyperplastic-like colon polyps that preceded microsatellite-unstable adenocarcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol 2003;119:778–796.

Hawkins NJ, Bariol C, Ward RL . The serrated neoplasia pathway. Pathology 2002;34:548–555.

Higuchi T, Jass JR . My approach to serrated polyps of the colorectum. J Clin Pathol 2004;57:682–686.

Snover DC, Jass JR, Fenoglio-Preiser C, et al. Serrated polyps of the large intestine: a morphologic and molecular review of an evolving concept. Am J Clin Pathol 2005;124:380–391.

Torlakovic E, Skovlund E, Snover DC, et al. Morphologic reappraisal of serrated colorectal polyps. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:65–81.

Jass JR . Serrated route to colorectal cancer: back street or super highway? J Pathol 2001;193:283–285.

Higuchi T, Sugihara K, Jass JR . Demographic and pathological characteristics of serrated polyps of colorectum. Histopathology 2005;47:32–40.

Wynter CV, Walsh MD, Higuchi T, et al. Methylation patterns define two types of hyperplastic polyp associated with colorectal cancer. Gut 2004;53:573–580.

Sheridan TB, Fenton H, Lewin MR, et al. Sessile serrated adenomas with low- and high-grade dysplasia and early carcinomas: an immunohistochemical study of serrated lesions ‘caught in the act’. Am J Clin Pathol 2006;126:564–571.

Longacre TA, Fenoglio-Preiser CM . Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps/serrated adenomas. A distinct form of colorectal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 1990;14:524–537.

Yantiss RK, Oh KY, Chen YT, et al. Filiform serrated adenomas: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:1238–1245.

Glatz K, Pritt B, Glatz D, et al. A multinational, internet-based assessment of observer variability in the diagnosis of serrated colorectal polyps. Am J Clin Pathol 2007;127:938–945.

Spring KJ, Zhao ZZ, Karamatic R, et al. High prevalence of sessile serrated adenomas with BRAF mutations: a prospective study of patients undergoing colonoscopy. Gastroenterology 2006;131:1400–1407.

Chan TL, Zhao W, Leung SY, et al. BRAF and KRAS mutations in colorectal hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas. Cancer Res 2003;63:4878–4881.

O'Brien MJ, Yang S, Clebanoff JL, et al. Hyperplastic (serrated) polyps of the colorectum: relationship of CpG island methylator phenotype and K-ras mutation to location and histologic subtype. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:423–434.

Yang S, Farraye FA, Mack C, et al. BRAF and KRAS mutations in hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas of the colorectum: relationship to histology and CpG island methylation status. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:1452–1459.

Byrd JC, Bresalier RS . Mucins and mucin binding proteins in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2004;23:77–99.

Corfield AP, Carroll D, Myerscough N, et al. Mucins in the gastrointestinal tract in health and disease. Front Biosci 2001;6:D1321–D1357.

Moniaux N, Escande F, Porchet N, et al. Structural organization and classification of the human mucin genes. Front Biosci 2001;6:D1192–D1206.

Hirono H, Ajioka Y, Watanabe H, et al. Bidirectional gastric differentiation in cellular mucin phenotype (foveolar and pyloric) in serrated adenoma and hyperplastic polyp of the colorectum. Pathol Int 2004;54:401–407.

Jass JR, Burt R . Hyperplastic polyposis In: Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA (eds) Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. IARC Press: Lyon, 2000, pp 135–136.

Kuan SF, Montag AG, Hart J, et al. Differential expression of mucin genes in mammary and extramammary Paget's disease. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1469–1477.

Al-Daraji WI, Montgomery E . Serrated polyps of the large intestine: a practical approach. Pathol Case Rev 2007;12:129–135.

Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Noffsinger AE, Stemmermann GN, et al. Carcinomas and other epithelial and neuroendocrine tumors of the large intestine. Gastrointestinal Pathology: An Atlas and Text, 2nd edn. Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia, 1999, pp 909–1068.

Higaki S, Akazawa A, Nakamura H, et al. Metaplastic polyp of the colon develops in response to inflammation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999;14:709–714.

Koike M, Inada K, Nakanishi H, et al. Cellular differentiation status of epithelial polyps of the colorectum: the gastric foveolar cell-type in hyperplastic polyps. Histopathology 2003;42:357–364.

Buisine MP, Desreumaux P, Leteurtre E, et al. Mucin gene expression in intestinal epithelial cells in Crohn's disease. Gut 2001;49:544–551.

Longman RJ, Douthwaite J, Sylvester PA, et al. Coordinated localisation of mucins and trefoil peptides in the ulcer associated cell lineage and the gastrointestinal mucosa. Gut 2000;47:792–800.

Sakai H, Jinawath A, Yamaoka S, et al. Upregulation of MUC6 mucin gene expression by NFkappaB and Sp factors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005;333:1254–1260.

Batts KP . Serrated colorectal polyps: an update. Pathol Case Rev 2004;9:173–182.

Gervaz P, Bucher P, Morel P . Two colons-two cancers: paradigm shift and clinical implications. J Surg Oncol 2004;88:261–266.

Iacopetta B . Are there two sides to colorectal cancer? Int J Cancer 2002;101:403–408.

Sorbi D, Conio M . Endoscopic resection of large sessile colorectal polyps using a submucosal saline injection technique. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;50:448–449.

Merati K, Wen P, De Lott LB, et al. Microsatellite stable and unstable mucinous colorectal adenocarcinomas show similar expression profiles for MUC1, MUC2, MUC4 and MUC5AC but differ in MUC6. Mod Pathol 2005;18:112A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any real or potential conflict of interest to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Owens, S., Chiosea, S. & Kuan, SF. Selective expression of gastric mucin MUC6 in colonic sessile serrated adenoma but not in hyperplastic polyp aids in morphological diagnosis of serrated polyps. Mod Pathol 21, 660–669 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2008.55

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2008.55

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Platform-independent gene expression signature differentiates sessile serrated adenomas/polyps and hyperplastic polyps of the colon

BMC Medical Genomics (2017)

-

MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6 in colorectal cancer: expression profiles and clinical significance

Virchows Archiv (2016)

-

Improved molecular classification of serrated lesions of the colon by immunohistochemical detection of BRAF V600E

Modern Pathology (2014)

-

Defined morphological criteria allow reliable diagnosis of colorectal serrated polyps and predict polyp genetics

Virchows Archiv (2014)

-

Annex to Quirke et al. Quality assurance in pathology in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis: annotations of colorectal lesions

Virchows Archiv (2011)