Abstract

The distinction of complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia from endometrial adenocarcinoma is often problematic. Foci of back-to-back arrangement of glands or foci of cribriform arrangement of glands smaller than 2.1 mm in diameter are considered insufficient for the diagnosis of endometrial adenocarcinoma by some authors, and sufficient to be diagnosed as endometrial adenocarcinoma by other authors. We refer to these foci as endometrial adenocarcinoma in situ. In this study, we evaluated findings in subsequent hysterectomy in complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia patients with and without adenocarcinoma in situ. Follow-up findings, including the presence or absence of endometrial adenocarcinoma in the hysterectomy specimen, the grade of the carcinoma and the depth of myometrial invasion were analyzed. Of the total 87 patients with complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia, 33 patients had adenocarcinoma in situ and 54 lacked adenocarcinoma in situ. Of 33 patients 22 (66%) with adenocarcinoma in situ had endometrial adenocarcinoma on subsequent hysterectomy vs 13 of 54 (24%) patients without adenocarcinoma in situ (P=0.0001). Myoinvasive endometrial adenocarcinoma was present in 20 of 33 (61%) patients with adenocarcinoma in situ vs 8 of the 54 (15%) patients without adenocarcinoma in situ (P≤0.0001). The depth of myometrial invasion in cases with myoinvasion was 24.5+19.4% in patients with adenocarcinoma in situ and12.8+8.5% in patients without adenocarcinoma in situ (P=0.05). Among patients younger than age of 50, 5 of the 7 (71%) with adenocarcinoma in situ had myoinvasive carcinoma vs 2 of the 13 (15%) without adenocarcinoma in situ (P=0.02). The likelihood of finding endometrial adenocarcinoma in subsequent hysterectomy in patients with complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia is significantly increased if adenocarcinoma in situ is present in prior endometrial sampling. Endometrial adenocarcinomas in patients with adenocarcinoma in situ are far more frequently myoinvasive, and invade to a greater depth than endometrial adenocarcinomas seen in patients without adenocarcinoma in situ. Use of adenocarcinoma in situ terminology could lead to improved management of patients with complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The distinction of complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia from endometrial adenocarcinoma is frequently problematic.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Foci of back-to-back arrangement of glands or foci of cribriform arrangement of glands smaller than 2.1 mm in diameter are considered insufficient for the diagnosis of endometrial adenocarcinoma by some authors,11 and sufficient to be diagnosed as endometrial adenocarcinoma by other authors.10 We have referred to these foci as endometrial adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) in the past. We have previously shown that the presence of such foci in complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia is associated with increased risk of finding endometrial carcinoma in subsequent hysterectomy.12 In the current study we have used a larger number of cases of complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia from three different centers to further evaluate this association.

Materials and methods

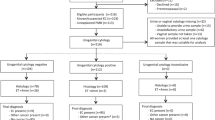

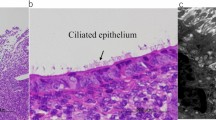

Cases with the diagnosis of complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia on endometrial curettage/biopsy and subsequent hysterectomy were examined for the presence of AIS. The cases were seen at New York University Medical Center, New York; North Broward Medical Center, Deerfield Beach, FL, and at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, PA. The cases were retrieved by searching for cases with the diagnosis of complex endometrial hyperplasia in the computerized records in each facility. The cases were sequential and seen from 2003 to 2006. Scant or otherwise suboptimal specimens were excluded from the study. The presence or absence of AIS was diagnosed at each facility based on review of the case by individual pathologists. Cytologic features were not included as a criteria for exclusion of a case, but none of the cases had grade III nuclei. The review of biopsies was done blindly without knowledge of the hysterectomy findings. Hysterectomy diagnosis of record was used. AIS was defined as foci of back-to-back arrangement of glands or foci of cribriform arrangement of glands composed of at least four glands and smaller than 2.1 mm in diameter (Figures 1, 2 and 3). Foci with marked glandular crowding, where stromal cells were readily identified between adjacent glands, were not considered AIS. Artifactual cribriform arrangement of glands such as appearance can be seen when there is squamous metaplasia or morule formation in endometrial glands, and these were also not included as AIS (Figure 4). The size of the largest AIS focus was noted in each case. Follow-up findings in the two groups of patients with and without AIS were analyzed, including the presence or absence of carcinoma in the hysterectomy specimen, the grade of the carcinoma and the depth of myometrial invasion.

Results

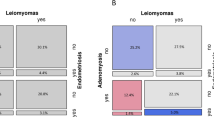

There were a total of 87 patients with complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia. The incidence of endometrial adenocarcinoma was 40% (35 of 87) and of myoinvasive carcinoma 32% (28 of 87) in subsequent hysterectomy in the entire group. All carcinomas were of endometrioid histology, and either grades I or II. Thirty-three patients (38%) had AIS and fifty-four (62%) lacked AIS. Twenty two of 33 (66%) patients with AIS had endometrial adenocarcinoma on subsequent hysterectomy vs 13 of 54 (24%) patients without AIS (P=0.0001). Myoinvasive adenocarcinoma was present in 20 of 33 (61%) patients with AIS vs 8 of the 54 (15%) patients without AIS (P<0.0001). Myoinvasive carcinoma to a depth of 2 mm or more was present in 20 of the 33 (61%) patients with AIS vs 6 of the 54 (11%) patients without AIS (P<0.0001). Myoinvasive carcinoma to a depth of 3 mm or more was present in 15 of the 33 (45%) patients with AIS vs 2 of the 54 (4%) patients without AIS (P<0.0001). The depth of myometrial invasion in cases with myoinvasion was 24.5±19.4% in patients with AIS and 12.8±8.5% in patients without AIS (P=0.05). The absolute depth of invasion in myoinvasive cases was 4.8±3.5 mm in patients with AIS and 2.1±1 mm in patients without AIS (P=0.01). A depth of invasion of greater than 50% was seen in 3 of the 33 patients with AIS, but in none of the 54 patients without AIS (P=0.05). None of the carcinomas in either group were FIGO grade III. The larger size of the AIS focus (>1 to <2.1 mm vs 1 mm or smaller) was not predictive of subsequent carcinoma (P=0.68). The results are summarized in Table 1.

Patients Younger than Age of 50

Among patients younger than age of 50, 5 of the 7 (71%) with AIS had myoinvasive carcinoma vs 2 of the 14 (14%) without AIS (P=0.02). In all five patients that had myoinvasive carcinoma in the AIS group, the depth of invasion was 3 mm or greater. One of these patients had myoinvasion of 1 cm, equal to 58% of myometrial thickness. The two patients in the group without AIS had 1 and 2 mm depth of invasion, respectively. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Discussion

The overall incidence of endometrial adenocarcinoma and myoinvasive endometrial adenocarcinoma on follow-up hysterectomy in the group of complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia patients reported here was similar to what has been reported in the literature.6, 7, 11, 13, 14 We found that the presence of AIS in complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia patients was associated with significantly greater likelihood of finding endometrial adenocarcinoma and myoinvasive endometrial adenocarcinoma on subsequent hysterectomy. Approximately two-thirds of patients with AIS in endometrial curettage/biopsy have endometrial adenocarcinoma on subsequent hysterectomy vs about a quarter of those that lack AIS. Endometrial adenocarcinomas in patients with AIS are far more frequently myoinvasive, and invade to a greater depth than carcinomas seen in patients that have complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia without AIS.

There is considerable confusion in the literature as to where complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia ends and endometrial adenocarcinoma starts. The distinction of endometrial carcinoma from complex endometrial hyperplasia has generally been based on the criteria proposed by Kurman and Norris nearly 25 years ago.11, 15, 16 In these studies, the cut off for endometrial carcinoma was arbitrarily set at 2.1 mm lesional size showing features of ‘stromal invasion’. However, 7 of the 89 patients that lacked ‘stromal invasion’ also showed myoinvasive carcinoma in that study. It is unclear if any of these seven patients with myoinvasive carcinoma had AIS. This group without ‘stromal invasion’ included cases with complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia and ‘carcinoma-in situ’, but separate follow-up data for patients in complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia and ‘carcinoma-in situ’ groups was not provided.11 In other words, no data were presented regarding the outcome of patients that showed smaller foci of what was called ‘stromal invasion’. Such lesions are diagnosed as complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia by some pathologists,11 as endometrial adenocarcinoma by others,10 and as endometrial adenocarcinoma cannot be ruled out by yet others. King et al17 examined a group of patients that they called ‘adenocarcinoma without stromal invasion’ and found endometrial carcinoma in 28% (12 of 43) and myoinvasive carcinoma in 16% (7 of 43) of these patients on follow-up hysterectomy. Longacre at al18 have shown that glandular complexity captured by a pictorial architectural index, along with nuclear pleomorphism and prominence of the nucleoli are features most predictive for the presence of myoinvasive carcinoma in complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia. They also reported that extensive squamous differentiation and fibroblastic stroma do not contribute to prediction of myoinvasive endometrial carcinoma in subsequent hysterectomy. Hendrickson et al19 did not find fibrous stroma in curettings from most patients with subsequent myoinvasive endometrial carcinoma.

We propose that foci of back-to-back glands or cribriform arrangement of glands smaller than 2.1 mm across be classified as AIS. The term ‘carcinoma-in situ’ was mistakenly applied to eosinophilic metaplasia of the endometrium many years ago20 is no longer used in that context. The concept of designating small foci of cribriform arrangement of glands in endometrium as ‘carcinoma-in situ’ is not entirely new, and has been used in the past by Welch and Scully,21 by Vellios22 and by Buehl et al.23 This concept, however, was not strictly defined previously, its definition varied from author to author, and follow-up data on these cases was not published. World Health Organization did not include any form of carcinoma-in situ of endometrium in its classification24 because of lack of agreement on its definition.21 In the current study, we have provided a strict definition for AIS of the endometrium, and documented its prognostic significance.

The relationship between AIS diagnosed preoperatively and endometrial adenocarcinoma found in hysterectomy specimens is unclear. Some lesions might represent smaller foci of the same neoplasm whereas others might represent independent and incompletely developed, incipient invasive carcinomas or risk lesions. The following observations support the latter possibility in some cases. Multiple foci of AIS can be seen without associated endometrial adenocarcinoma. Foci of AIS are often fairly widely distributed, with intervening areas of complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia. We have also seen cases where the histomorphologic appearance of these foci varies, suggesting their independent origin from each other (Figure 5).

Although we prefer to use the term AIS, a number of alternative terms could be potentially used for this lesion. These would include terms such as CAH types I and II, CAH type A and B, endometrial adenocarcinoma without stromal invasion, minimal carcinoma, microcarcinoma, microinvasive carcinoma, CAH with focal glandular confluence and ‘microscopic focus of adenocarcinoma’.

AIS of endometrium should not be confused with endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma (EIC),25 which is an early form of uterine serous carcinoma characterized by growth of cells with high-grade nuclei on the endometrial surface and in glands. These cells usually overexpress p53. Cribriform arrangement of glands or back-to-back arrangement of glands is not seen in EIC. EIC usually arises in the background of an atrophic endometrium.

Recognition of the substantial risk of myometrial invasion following a diagnosis of AIS should allow gynecologists and patients to make better informed decisions when conservative, nonsurgical management is considered. In the current study, only 2 of the 14 patients with complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia without AIS age 50 or under had myoinvasion, which was 1 and 2 mm, respectively. Two had carcinoma confined to the endometrium, whereas 10 had no carcinoma. Thus these patients can be managed conservatively. In contrast 5 of the 7 patients, 50 or under with complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia with AIS had myoinvasive carcinoma, and the depth of invasion in each of the five patients was 3 mm or more. One patient had 58% depth of invasion. Patients with complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia with AIS may also be considered for lymph node sampling at hysterectomy if these lymph nodes are enlarged.

In Summary, presence of AIS should be looked for and reported by pathologists in endometrial biopsies showing complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia because of a significantly greater likelihood of finding endometrial adenocarcinoma and myoinvasive endometrial adenocarcinoma in subsequent hysterectomy if AIS is present.

References

Allison KH, Reed SD, Voigt LF, et al. Diagnosing endometrial hyperplasia: why is it so difficult to agree?. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:691–698.

Hecht JL, Ince TA, Baak JP, et al. Prediction of endometrial carcinoma by subjective endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia diagnosis. Mod Pathol 2005;18:324–330.

Bergeron C, Nogales FF, Masseroli M, et al. A multicentric European study testing the reproducibility of the WHO classification of endometrial hyperplasia with a proposal of a simplified working classification for biopsy and curettage specimens. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:1102–1108.

Kendall BS, Ronnett BM, Isacson C, et al. Reproducibility of the diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia, atypical hyperplasia, and well-differentiated carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:1012–1019.

Skov BG, Broholm H, Engel U, et al. Comparison of the reproducibility of the WHO classifications of 1975 and 1994 of endometrial hyperplasia. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1997;16:33–37.

Dunton CJ, Baak JP, Palazzo JP, et al. Use of computerized morphometric analyses of endometrial hyperplasias in the prediction of coexistent cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174:1518–1521.

Zaino RJ, Kauderer J, Trimble CL, et al. Reproducibility of the diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer 2006;106:804–811.

Silverberg SG . Problems in the differential diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2000;13:309–327.

Soslow RA . Problems with the current diagnostic approach to complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cancer 2006;106:729–731.

Silverberg SG . Hyperplasia and carcinoma of the endometrium. Semin Diagn Pathol 1988;5:135–153.

Kurman RJ, Norris HJ . Evaluation of criteria for distinguishing atypical endometrial hyperplasia from well-differentiated carcinoma. Cancer 1982;49:2547–2559.

Ventura KC, Popiolek D, Mittal K . Endometrial adenocarcinoma in situ in complex atypical hyperplasia: correlation with findings in subsequent hysterectomy specimen. Int J Surg Pathol 2004;12:225–230.

Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, et al. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer 2006;106:812–819.

Widra EA, Dunton CJ, McHugh M, et al. Endometrial hyperplasia and the risk of carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 1995;5:233–235.

Kurman RJ, Kaminski PF, Norris HJ . The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of ‘untreated’ hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer 1985;56:403–412.

Norris HJ, Tavassoli FA, Kurman RJ . Endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. Diagnostic considerations. Am J Surg Pathol 1983;7:839–847.

King A, Seraj IM, Wagner RJ . Stromal invasion in endometrial adenocarcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984;149:10–14.

Longacre TA, Chung MH, Jensen DN, et al. Proposed criteria for the diagnosis of well-differentiated endometrial carcinoma. A diagnostic test for myoinvasion. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:371–406.

Hendrickson MR, Ross JC, Kempson RL . Toward the development of morphologic criteria for well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Am J Surg Pathol 1983;7:819–838.

Hertig AT, Sommers SC, Bengloff H . Genesis of endometrial carcinoma III. Carcinoma in situ. Cancer 1949;Volume: 2:964–971.

Welch WR, Scully RE . Precancerous lesions of the endometrium. Hum Pathol 1977;8:503–512.

Vellios F . Endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma in-situ. Gynecol Oncol 1974;2:152–161.

Buehl IA, Vellios F, Carter JE, et al. Carcinoma in situ of the endometrium. Am J Clin Path 1964;42:594–601.

Poulson HE, Taylor CW . International Histological Classification of Tumours no 13 Histological Typing of Female Genital Tract Tumours. World Health Organization: Geneva, 1975.

Ambros RA, Sherman ME, Zahn CM, et al. Endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma: a distinctive lesion specifically associated with tumors displaying serous differentiation. Hum Pathol 1995;26:1260–1267.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mittal, K., Sebenik, M., Irwin, C. et al. Presence of endometrial adenocarcinoma in situ in complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia is associated with increased incidence of endometrial carcinoma in subsequent hysterectomy. Mod Pathol 22, 37–42 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2008.138

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2008.138

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Clinical and Metabolic Response to Vitamin D Supplementation in Endometrial Hyperplasia: a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

Hormones and Cancer (2017)

-

Endometriale Karzinome und Vorstufen – Neue Aspekte

Der Pathologe (2009)