Abstract

The study was designed to compare clofarabine plus daunorubicin vs daunorubicin/ara-C in older patients with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Eight hundred and six untreated patients in the UK NCRI AML16 trial with AML/high-risk MDS (median age, 67 years; range 56–84) and normal serum creatinine were randomised to two courses of induction chemotherapy with either daunorubicin/ara-C (DA) or daunorubicin/clofarabine (DClo). Patients were also included in additional randomisations; ± one dose of gemtuzumab ozogamicin in course 1; 2v3 courses and ± azacitidine maintenance. The primary end point was overall survival. The overall response rate was 69% (complete remission (CR) 60%; CRi 9%), with no difference between DA (71%) and DClo (66%). There was no difference in 30-/60-day mortality or toxicity: significantly more supportive care was required in the DA arm even though platelet and neutrophil recovery was significantly slower with DClo. There were no differences in cumulative incidence of relapse (74% vs 68%; hazard ratio (HR) 0.93 (0.77–1.14), P=0.5); survival from relapse (7% vs 9%; HR 0.96 (0.77–1.19), P=0.7); relapse-free (31% vs 32%; HR 1.02 (0.83–1.24), P=0.9) or overall survival (23% vs 22%; HR 1.08 (0.93–1.26), P=0.3). Clofarabine 20 mg/m2 given for 5 days with daunorubicin is not superior to ara-C+daunorubicin as induction for older patients with AML/high-risk MDS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although progress has been made with intensive treatments for younger patients with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML),1, 2 improvement in older patients given the same schedules is much more modest.3, 4 This is usually attributed to the higher frequency of disease with adverse biological features than in younger patients, which responds less frequently and for shorter duration. The other difference is that co-morbidities accumulate with age, whether apparent or not, and the tolerance to intensive therapy is poorer with a higher risk of induction mortality and reduced ability to deliver the total planned treatment.5, 6 More effective treatments are therefore required, which are both more efficacious and also have better tolerability.

Clofarabine (2-chloro-2′-fluoro-deoxy-9-ß-d-arabinofuranosyladenine) is a novel nucleoside analogue which was developed in a large screening programme to find new therapeutics which incorporate the beneficial properties of this class of drugs. In particular, fludarabine and cladribine are active as single agents in AML but at dose levels associated with prohibitive toxicity, which is due to the cleavage product 2-fluoroadenine being converted to toxic 2-fluoroadenosine.7, 8 Clofarabine is the result of a programme of development exploring a series of chemical modifications to minimise cleavage while retaining activity.9 It depends on membrane nucleoside transporters for cell entry and is sequentially phosphorylated in deoxycytidine kinase-dependent steps to the triphosphate, the active form of which is retained within cells for longer than other purine nucleoside analogues. Following initial studies in relapsed disease which confirmed its activity,10 two reports incorporating three un-randomised studies11, 12 assessed the front-line activity using lower doses in older patients who were considered unfit for intensive therapy. These studies were consistent in delivering complete remission to more than 40% of patients, and of interest this responsiveness did not seem to be limited by age or cytogenetic risk group. Given its favourable toxicity profile, potential for oral administration and similarity to fludarabine, it became a potential candidate novel therapy for the older patient. These trials did not establish the duration of response. In one of these pilot trials no renal function restriction was required, hence a dose level of 20 mg/m2 was tested in a small number of patients against the conventional 30 mg/m2 dose and produced a similar efficacy, but with a more favourable toxicity profile.11

On this basis we conducted a randomised trial in patients not considered suitable for intensive therapy, comparing clofarabine at a daily dose of 20 mg/m2 for five consecutive days, with low-dose ara-C (20 mg b.i.d. for 10 days).13 The remission rate was doubled by clofarabine, but overall survival (OS) was not improved because the survival of patients who failed to achieve complete remission on the clofarabine arm was worse, and when patients relapsed from a clofarabine-induced remission their survival was poorer than for those who relapsed from low-dose ara-C. In the current study as part of the United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) AML16 Trial (ISRCTN 11036523), we wished to test clofarabine combined with daunorubicin vs ara-C combined with daunorubicin as induction therapy for older patients for whom conventional therapy was indicated.

Patients and methods

The protocol was designed for older patients, generally age >60 years, who did not have blast transformation of chronic myeloid leukemia or acute promyelocytic leukemia. Patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), which was defined as >10% marrow blasts at diagnosis, were eligible. A small number of patients aged <60 years, who were not considered suitable for the concurrent AML15 trial for younger patients (which included high-dose ara-C), were included. Secondary AML was defined as resulting from either antecedent haematologic disorder or prior chemotherapy treatment for a non-haematological malignancy. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki; it was sponsored by Cardiff University and was approved by Wales REC 3. All patients provided written informed consent to random treatment assignment. Patients were randomly assigned between two courses of chemotherapy comprising daunorubicin/ara-C or daunorubicin/clofarabine. To be eligible for randomisation assignment, patients were required to have serum creatinine within local normal limits.

The treatment plan is set out in Figure 1 and the number of patients in the DClo vs DA induction randomisation who entered these randomisations is included in Table 1.

The median age of the patients was 67 years (range 56–84), 59% were male, 72% had de novo AML, 17% secondary AML and 11% had high-risk MDS. Six percent had a WHO performance score of >2; 14% had an FLT3 mutation and 20% had an NPM1c mutation. The cytogenetic risk category as previously defined14 was 4% favourable, 73% intermediate and 23% adverse risk. Using the validated Wheatley Risk Score,15 which is based on age, cytogenetics, presenting white count, presence of secondary disease and performance status, three risk groups were defined (30% were good, 34% standard and 36% poor) with survival at 2 years of 29, 17 and 9%, respectively.

Statistical methods

The primary outcome measure for the trial was OS. The study was powered to detect a difference of 10% in absolute 2-year survival from 25 to 35% (equivalent to hazard ratio (HR) of 0.76), with 90% power at P<0.05. This required a minimum of 552 deaths, and at least 800 patients had to be recruited. Secondary end points were achievement of complete remission (CR), CR with incomplete peripheral count recovery (CRi), relapse-free survival, relapse and death in remission (the last three for patients achieving either CR or CRi), together with resource use and toxicity (haematologic recovery times and non-haematologic toxicity scored using National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, Version 3).

All end points were defined according to the revised International Working Group criteria,16 including the use of competing-risks methodology to estimate cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR), with the exception that in the protocol as written, the definition of CR did not require count recovery; however, because these data were routinely available, in this report, we divided patients into those who achieved CR by International Working Group criteria and those who instead achieved CRi. On the recommendation of the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee, the trial was analyzed once a minimum of 1-year follow-up was available and a minimum of 552 deaths had been observed. Follow-up was complete for 98% of patients to 1 March 2015; follow-up for patients was censored on the date they were last known to be alive. Median follow-up was calculated using reverse censoring. Survival for patients withdrawing from follow-up was censored on the date of withdrawal; one patient withdrew consent in this cohort. All analyses were performed by intention to treat; time-to-event data were summarised using Kaplan–Meier or cumulative incidence estimates and analyzed using the log-rank test, with the Mantel–Haenszel test used for dichotomous outcomes such as remission. Resource usage and toxicity data were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. As per the statistical analysis plan, analyses of outcome were performed, stratified by the randomisation stratification parameters (age, WBC, WHO performance status, type of disease (de novo, secondary, high-risk MDS), and entry into the other induction randomisation) as well as the cytogenetic group (defined using the MRC classification14) and other potentially important factors, such as FLT3-ITD and NPM1 mutations. Such stratified analyses are presented in Forest plots using standard meta-analytic techniques, with suitable tests for interaction (trend or heterogeneity) performed. Because the trial was designed factorially, later randomisations did not affect the results of the induction randomisations, because allocation was stratified for treatment received in induction.

The results of the gemtuzumab ozogamicin randomisation have already been reported in full,17 and the consolidation and maintenance randomisations will be reported elsewhere.

Minimal residual disease assessment by flow cytometry, with a sensitivity of 1 × 104, was undertaken in 135 of 410 randomised patients who were in morphological remission after the first induction course. The methods have been described in detail elsewhere.18 Samples of bone marrow were collected after recovery from 135 patients in CR post course and 154 patients in CR post course 2.

Results

Between August 2006 and December 2008, 806 untreated patients from 124 centres in the UK, Denmark and New Zealand were randomised to receive either two induction courses of DClo: daunorubicin 50 mg/m2 on days 1, 3 and 5 combined with clofarabine 20 mg/m2 on days 1–5, or two courses of DA: daunorubicin 50 mg/m2 combined with ara-C 100 mg/m2 b.i.d. days 1–10 in course 1 and days 1–8 in course 2. Fifty-nine patients were excluded from the randomisation based on renal criteria and were allocated to the daunorubicin/ara-C induction, but were eligible to be considered for the other trial randomisations.

The other interventions included gemtuzumab ozogamicin 3 mg/m2 or not in course 1. Patients who achieved a complete remission (CR), complete remission with incomplete platelet recover (CRi), or a partial remission (<15% blasts in the bone marrow) in response to course 1 and were in CR after 2 induction courses were eligible to be randomised to have a single consolidation course (daunorubicin 50 mg/m2 on days 1 and 3 combined with ara-C 100 mg/m2 b.i.d. on days 1–5) or no consolidation, and to receive, or not receive, maintenance treatment with azacitidine 75 mg/m2 for 5 days every 6 weeks for 12 months (9 courses). The disposition of patients is shown in the CONSORT diagram (Figure 2).

The compliance with the allocated treatment was 98% and the overall response rate (CR+CRi) was 68% and survival at 5 years is 15%.

Remission induction

The results of induction treatment are summarised in Table 2. Overall, 61% of patients entered CR, and an additional 7% achieved marrow remission with incomplete recovery of peripheral blood counts (i.e. CRi). Remission (CR or CRi) was recorded after course one in 51% of patients; after course two, in an additional 14%. In 3% of patients remission took more than two courses. There was a trend for a superior CR rate in the DA patients 64% vs DClo, 58% (OR 1.30 (0.98–1.73), P=0.07), and an additional 6 and 8%, respectively, achieved a CRi; thus, the overall response rate was 71% vs 66% (HR 1.26 (0.94–1.70), P=0.12). The induction deaths were not different (11% vs 11%; OR 0.99 (0.64–1.55), P=1.0) and 30-day (9% vs 8%) and 60-day (15% vs 14%) mortalities were not significantly different (Table 2).

In the samples in morphological remission which were assessed for MRD, the positivity after course 1 in the DA patients was 52% and in the DClo patients was 54% (P=0.9). After course 2 the MRD positivity was 34 and 39%, respectively (P=0.5). There was no suggestion of a benefit of any particular demographic or cytogenetic subgroup, whether an FLT3 or NPM1c mutation as present or whether the patient received gemtuzumab ozogamicin or not (Supplementary Figure S1).

Toxicity

With the exception of diarrhoea (12% with DA in course 1) and nausea (10% with DClo in course 1), no grade 3 or 4 toxicity was recorded in more than 10% of patients on either treatment arm during either induction courses (Table 3). The median day of recovery of neutrophils and platelets measured from the end of the course was significantly longer in the DClo arm (neutrophils 20 vs 24 days, P<0.0001; platelets 21 vs 24 days, P<0.0001). Significantly more red cell and platelet transfusions, days on antibiotic and days in hospital were required after course 1 in the DA arm (Table 3). There was little difference in transfusion requirement after course 2.

Relapse

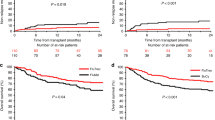

The five-year cumulative incidence of relapse (Figure 3a) was 75% (DA 78% vs DClo 72%; HR 0.93 (0.77–1.13), P=0.5). In the exploratory analysis of subgroups no differences were found (Supplementary Figure S2). The respective survival from relapse (Figure 3b) was also not different (4% vs 8%; HR 0.92 (0.75–1.13), P=0.4).

Relapse-free survival

Death without relapse was nonsignificantly increased in the DClo arm (8% vs 13%; HR 1.47 (0.89–2.43), P=0.13). Taken together with the nonsignificant difference in relapse, no difference was found between the arms in relapse-free survival (14% vs 15%) (HR 0.99 (0.83–1.19), P=0.9; Figure 3c) or survival from CR (20% vs 23%; HR 0.96 (0.80–1.16), P=0.7; Figure 3d).

Overall survival

No difference was found in survival (DA 15%, DClo 14%; HR 0.96 (0.67–1.39), P=0.8; Figure 4a) either overall or within exploratory subgroups (Supplementary Figure S3). In particular, there was no significant interaction with any other treatments. There were no obvious differences between the causes of the 355 deaths on the DA arm vs the 347 on the DClo arm with about half in each case being due to refractory or recurrent disease (Figure 4b).

Discussion

The inability to develop an improved induction regimen for older patients with AML is a major issue, but it is also true for younger patients, such that the combination of daunorubicin and ara-C remains the standard of care. Variations in dose and scheduling of the two drugs have been explored in many studies in patients of all ages, but dose escalation options are limited in older patients.19, 20, 21, 22, 23 The general use of the higher dose (90 mg/m2) of daunorubicin was not of overall benefit in older patients although it did improve outcome in the subset aged 60–65 years when compared with a 45 mg/m2 dose level.20 Gemtuzumab ozogamicin in this NCRI AML16 trial when added to induction course 1 in a small dose of 3 mg/m2 produced an OS benefit, as it did in the French ALFA study in patients aged 50–70 years using a different schedule.17, 24 In our AML15 trial, which was intended for younger patients (<60 years), we observed a powerful antileukaemic effect when using the FLAG-Ida (fludarabine/ara-C/G-CSF/Idarubicin) combination,25 which is now being prospectively assessed in older patients.

Alternative nucleoside analogues have recently been explored in AML with mixed results. The addition of cladrabine26 to standard DA treatment appears promising particularly in younger patients with adverse risk cytogenetics. Single-agent sapacitabine in older unfit patients was not beneficial,27 but other studies in combination are underway or yet to be reported. Clofarabine as monotherapy has been rather ambitiously compared with standard 3+7 daunorubicin, but was unsuccessful.28 An obvious setting in which to assess clofarabine was as a replacement for ara-C in combination with an anthracycline. This had a number of attractions. First it had been developed as a 5-day schedule compared with the need for 7 or 10 days of ara-C. Second, in the preliminary studies it appeared to be equally effective in adverse risk patients who of course are well represented in an older population. Third, it had the prospect of being taken orally.

In the initial studies in relapsed disease undertaken by the MD Anderson group,10 the dose used was 40 mg/m2. However when initially targeting the older unfit patient population we felt that a lower dose of 30 mg/m2 would be wise. Even at this dose in unselected older patients some renal toxicity was observed, which required more rigorous entry criteria with respect to renal function. We also explored a lower daily dose of 20 mg/m2,11 which was found to be well tolerated, with less renal and hepatic biochemical abnormalities being seen, without any loss of efficacy. This dose level was then explored as monotherapy in older patients judged to be unfit for conventional therapy.11, 12 After a brief safety assessment of the combination with daunorubicin in older patients considered suitable candidates for intensive therapy,29 the randomised comparison was initiated. The results presented here provide no evidence overall, or in any subgroup, to suggest that ara-C should be replaced by clofarabine, at least at the 20 mg/m2 daily dose. Taken together, and acknowledging the issue of exploring higher doses in combination, the clinical experience so far does not suggest that clofarabine should displace existing treatments. New treatment options such as addition of inhibitors of FLT3, IDH1 and IDH2 hold promise, but also challenges because of the lower frequency of specific mutations in older patients. Of recent interest is the liposomal formulation of the combination of daunorubicin and ara-C (CPX-351) which is a novel way of delivering therapy and has proved to be more effective in older patients with secondary AML.30, 31

References

Burnett AK . Treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: are we making progress? Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2012; 2012: 1–6.

Burnett A, Wetzler M, Lowenberg B . Therapeutic advances in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 487–494.

Lowenberg B, Zittoun R, Kerkhofs H, Jehn U, Abels J, Debusscheret L et al. On the value of intensive remission induction chemotherapy in elderly patients of 65+ yrs. with acute myeloid leukemia. A randomized phase III study (AML-7) of the EORTC Leukemia Group. J Clin Oncol 1989; 7: 1268–1274.

Buchner T, Berdel WE, Haferlach C, Haferlach T, Schnittger S, Müller-Tidow C et al. Age-related risk profile and chemotherapy dose response in acute myeloid leukemia: a study by the German Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 61–69.

Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, Cortes J, Giles F, Faderl S, Jabbour E et al. Results of intensive chemotherapy in 998 patients age 65 years or older with acute myeloid leukemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: predictive prognostic models for outcome. Cancer 2006; 106: 1090–1098.

Appelbaum FR, Gundacker H, Head DR, Slovak ML, Willman CL, Godwin JE et al. Age and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2006; 107: 3481–3485.

Lindemalm S, Liliemark J, Juliusson G, Larsson R, Albertioni F . Cytotoxicity and pharmacokinetics of cladribine metabolite, 2-chloroadenine in patients with leukemia. Cancer Lett 2004; 210: 171–177.

Avramis V I, Plunkett W . 2-fluoro-ATP: a toxic metabolite of 9-beta-D-arabinosyl-2-fluoroadenine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1983; 113: 35–43.

Montgomery JA, Shortnacy-Fowler AT, Clayton SD, Riordan JM, Secrist JA 3rd . Synthesis and biologic activity of 2'-fluro-2-halo derivatives of 9-beta-D-arabinofuranosyladenine. J Med Chem 1992; 35: 397–401.

Kantarjian H, Gandhi V, Cortes J, Verstovsek S, Du M, Garcia-Manero G et al. Phase 2 clinical and pharmacologic study of clofarabine in patients with refractory or relapsed acute leukemia. Blood 2003; 102: 2379–2386.

Burnett AK, Russell NH, Kell J, Dennis M, Milligan D, Paolini S et al. European development of clofarabine as treatment for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia not considered unsuitable for intensive chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 2389–2395.

Kantarjian HM, Erba HP, Claxton D, Arellano M, Lyons RM, Kovascovics T et al. Phase II study of clofarabine monotherapy in previously untreated older adults with acute myeloid leukemia and unfavorable prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 549–555.

Burnett AK, Russell NH, Hunter AE, Milligan D, Knapper S, Wheatley K et al. Clofarabine doubles the response rate in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia but does not improve survival. Blood 2013; 122: 1384–1394.

Grimwade D, Walker H, Harrison G, Oliver F, Chatters S, Harrison CJ et al. The predictive value of hierarchical cytogenetic classification in older adults with AML: analysis of 1,065 patients entered into the MRC AML11 Trial. Blood 2001; 98: 1312–1320.

Wheatley K, Brookes CL, Howman AJ, Goldstone AH, Milligan DW, Prentice AG et alUnited Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute Haematological Oncology Clinical Studies Group and Acute Myeloid Leukaemia Subgroup. Prognostic factor analysis of the survival of elderly patients with AML in the MRC AML11 and LRF AML14. Br J Haematol 2009; 145: 598–605.

Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, Büchner T, Willman CL, Estey EH et al. Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 4642–4649.

Burnett AK, Russell NH, Hills RK, Kell J, Freeman S, Kjeldsen L et al. Addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy improves survival in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2012; 32: 3924–3931.

Freeman SD, Virgo P, Couzens S, Grimwade D, Russell NH, Hills RK et al. Prognostic relevance of treatment response measured by flow cytometric residual disease detection in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 4123–4131.

Fernandez HF, Sun Z, Yao X, Litzow MR, Luger SM, Paietta EM et al. Anthracycline dose intensification in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1249–1259.

Lowenberg B, Ossenkoppele GJ, van Putten W, Schouten HC, Graux C, Ferrant A et al. High-dose daunorubicin in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. N Eng. J Med 2009; 361: 1235–1248.

Lee JH, Joo YD, Kim H, Bae SH, Kim MK, Zang DY et al. A randomized trial comparing standard versus high-dose daunorubicin induction in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2011; 118: 3832–3841.

Weick JK, Kopecky KJ, Appelbaum FR, Head DR, Kingsbury LL, Balcerzak SP et al. A randomized investigation of high-dose versus standard dose cytosine arabinoside with daunorubicin in patients with previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia: A Southwest Oncology Group Study. Blood 1996; 88: 2841–2851.

Löwenberg B, Pabst T, Vellenga E, van Putten W, Schouten HC, Graux C et al. Cytarabine dose for acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2001; 364: 1027–1036.

Castaigne S, Pautas C, Terre C, Raffoux E, Bordessoule D, Bastie JN et al. Effect of gemtuzumab ozogamicin on survival of adult patients with de-novo acute myeloid leukaemia (ALFA-0701): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2012; 379: 1508–1516.

Burnett AK, Russell NH, Hills RK, Hunter AE, Kjeldsen L, Yin J et al. Optimization of chemotherapy for younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results of the medical research council AML15 trial. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 3360–3368.

Holowiecki J, Grosicki S, Giebel S, Robak T, Kyrcz-Krzemien S, Kuliczkowski K et al. Cladribine, but not fludarabine, added to daunorubicin and cytarabine during induction prolongs survival of patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a multicenter, randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 2441–2448.

Burnett AK, Russell N, Hills RK, Panoskaltsis N, Khwaja A, Hemmaway C et al. A randomised comparison of the novel nucleoside analogue sapacitabine with low-dose cytarabine in older patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia 2015; 29: 1312–1319.

Foran JM, Sun Z, Claxton DF, Lazarus HM, Thomas M, Melnick A et al. North American Leukemia‚ Intergroup Phase III Randomized Trial of single agent clofarabine as induction and post-remission therapy‚ and decitabine as maintenance therapy in newly-diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia in older adults (age ⩾ 60 years). A trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E2906). Blood 2015; 126: 23 (Abstr 217).

Burnett AK, Kell WJ, Hills RK et al. The feasibility of combining daunorubicin, clofarabine and gemtuzumab ozogamicin is feasible and effective. A pilot study. Blood 2006; 108: 1950.

Lancet JE, Cortes JE, Hogge DE, Tallman MS, Kovacsovics TJ, Damon LE et al. Phase 2 trial of CPX-351, a fixed 5:1 molar ratio of cytarabine-daunorubicin, vs cytarabine/daunorubicin in older adults with untreated AML. Blood 2014; 123: 3239–3246.

Cortes JE, Goldberg SL, Feldman EJ, Rizzeri DA, Hogge DE, Larson M et al. Phase II, multicenter, randomized trial of CPX-351 (cytarabine:daunorubicin) liposome injection versus intensive salvage therapy in adults with first relapse AML. Cancer 2015; 121: 234–242.

Acknowledgements

Cancer Research UK provided support for the research costs of the AML16 Trial. Clofarabine was generously provided by Genzyme. We are grateful to the staff of the Haematology Trials Unit, Cardiff University and to research staff and patients in the participating institutions. The research was funded by Cancer Research UK, and Clofarabine was generously provided by Genzyme.

The following institutions and clinicians recruited patients to the trial: Aalborg University Hospital: Dr Mette Skov Holm; Aarhus University Hospital: Dr J M Norgaard, Dr Jorn Starklint, Dr Mette Skov Holm; Aberdeen Royal Infirmary: Dr D J Culligan, Dr J Tighe, Dr Yen-Lin Chee; Addenbrooke's Hospital: Dr C Crawley, Dr J Craig, Dr R E Marcus; Arrowe Park Hospital: Dr Nauman Butt; Barnet General Hospital: Dr A Virchis, Dr Sylvia Berney; Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospital: Dr Alison Milne; Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospital: Dr Sylwia Simpson; Belfast City Hospital: Dr F Jones, Dr Mary Frances McMullin, Dr R J G Cuthbert; Birmingham Heartlands Hospital: Dr D W Milligan, Dr G E D Pratt, Dr Joanne Ewing, Dr Neil Smith, Dr Richard Lovell, Dr Shankara Paneesha; Blackpool Victoria Hospital: Dr P A Cahalin; Borders General Hospital: Dr Ashok Okhandiar, Dr J Tucker; Bradford Royal Infirmary: Dr A T Williams, Dr Anita Hill; Bristol Haematology & Oncology Centre: Dr G R Standen, Dr J M Bird, Dr P Mehta, Dr R Evely, Dr S Robinson; Cheltenham General Hospital: Dr A Rye, Dr E Blundell, Dr J Ropner, Dr R Lush; Chesterfield & North Derbyshire Royal Hospital: Dr M Wodzinski; Christie Hospital: Dr Adrian Bloor, Dr E Liakopoulou, Dr M Dennis; City Hospitals Sunderland: Dr Lucy Pemberton, Dr MJ Galloway, Dr Yogesh Upadhye; Colchester General Hospital: Dr Gavin Campbell, Dr MT Hamblin; Countess Of Chester Hospital: Dr E Lee; Crosshouse Hospital: Dr M Mccoll, Dr P Maclean, Dr Paul Eynaud; Croydon University Hospital: Dr CM Pollard, Dr Nnenna Osuji; Derbyshire Royal Infirmary: Dr A Mckernan, Dr Cherry Chang, Dr G Sidra, Dr R Faulkner; Derriford Hospital: Dr Adrian Copplestone, Dr Hannah Hunter, Dr Mike Hamon, Dr Simon Rule, Dr Tim J Nokes; Dewsbury Hospitals: Dr K Patil; Doncaster Royal Infirmary: Dr B Paul, Dr S Kaul; Dorset County Hospital: Dr AH Moosa; Ealing Hospital: Dr G Abrahamson; Eastbourne District General Hospital: Dr J Beard, Dr P A Gover, Dr R J Grace; Falkirk Community Hospital: Dr R F Neilson; Gartnavel General Hospital: Dr M T J Leach, Dr Richard Soutar; Glasgow Royal Infirmary: Dr Andrew Clark; Gloucestershire Royal Hospital: Dr S Chown; Guy's Hospital: Dr Matthew Smith; Hemel Hempstead General Hospital: Dr A Wood, Dr J Harrison; Herlev University Hospital: Dr Carston Helleberg, Dr Inge Hoegh Dufva, Dr Morten Krogh Jensen; Hillingdon Hospital: Dr Ketan Patel, Dr R Kaczmarski; Hull Royal Infirmary: Dr C Carter, Dr S Ali; Ipswich Hospital: Dr J A Ademokun, Dr N J Dodd; James Paget Hospital: Dr Cesar Gomez, Dr Shalal Sadullah; Kent & Canterbury Hospital: Dr C F E Pocock, Dr F Zwaan, Dr K Saied, Dr V Ratnayake; Kettering General Hospital: Dr M Lyttleton, Dr Mark Kwan; Kingston Hospital: Dr H Sykes, Dr Z Abboudi; Leeds General Infirmary: Dr D T Bowen, Dr Rod Johnson; Leicester Royal Infirmary: Dr A E Hunter; Lincoln County Hospital: Dr K Saravanamuttu; Maidstone District General Hospital: Dr Richard F Gale, Dr Saad Rassam; Manchester Royal Infirmary: Dr G S Lucas, Dr J Burthem, Professor J A Liu Yin; Medway Maritime Hospital: Dr Ayed Eden, Dr Maadh Aldouri, Dr V E Andrews; Monklands Hospital: Dr J A Murphy, Dr Lindsay Mitchell; Musgrove Park Hospital: Dr S Bolam; New Cross Hospital: Dr A Jacob, Dr A MacWhannell, Dr S Basu, Dr Sunil Handa; Ninewells Hospital: Dr D Meiklejohn, Dr Duncan Ian Gowans, Dr Keith Gelly, Dr S Tauro; Norfolk & Norwich University Hospital: Dr Matthew Lawes; North Manchester General Hospital: Dr David Osbourne, Dr Hayley Greenfield; North Staffordshire Hospital: Dr A Stewart, Dr D Chandra, Dr David Allotey, Dr R C Chasty; Northwick Park Hospital: Dr N Panoskaltsis; Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust—City Hospital Campus: Dr E Das-Gupta, Dr J L Byrne, Professor N H Russell; Odense University Hospital: Dr Lone Friis; Pilgrim Hospital: Dr Ara Kiorkian, Dr K Saravanamuttu, Dr SS Sobolewski, Dr V Tringham; Pinderfields General Hospital: Dr D Wright, Dr John Ashcroft, Dr K Patil, Dr Paul Moreton; Poole General Hospital: Dr AJ Bell, Dr F Jack; Princess Royal University Hospital: Dr A Lakhani, Dr B Vadher, Dr C De Lord; Queen Alexandra Hospital: Dr M Ganczakowski, Dr R Corser; Queen Elizabeth Hospital (Kings Lynn): Dr AJ Keidan, Dr P Coates; Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham: Dr JA Murray, Professor Charles F Craddock; Queen's Hospital, Romford: Dr A Brownell, Dr I Grant, Dr Jane Stevens; Raigmore Hospital: Dr C Lush, Dr P Forsyth, Dr William Murray; Rigshospitalet University Hospital: Dr Jesper Jurlander, Dr Lars Kjeldsen, Dr Ole Weis Bjerrum, Dr Ove Juul Nielsen; Rotherham District General Hospital: Dr HF Barker, Dr P C Taylor; Royal Berkshire Hospital: Dr G Morgenstern, Dr Rebecca Sampson; Royal Bournemouth General Hospital: Dr S Killick; Royal Cornwall Hospital (Treliske): Dr A R Kruger, Dr Bryson Pottinger, Dr E Parkins, Dr R Noble; Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital (Wonford): Dr Anthony Todd, Dr Jackie Ruell, Dr M V Joyner, Dr Malcolm Hamilton, Dr R Lee; Royal Free Hospital: Dr A Mehta, Dr Christopher McNamara, Dr P Kottaridis; Royal Hallamshire Hospital: Dr C Dalley, Dr J Snowden, Professor JT Reilly; Royal Stoke University Hospital (University Hospital of North Midlands NHS Trust): Dr A Stewart; Royal Sussex County Hospital: Dr J Duncan, Dr Timothy Corbett; Royal United Hospital Bath: Dr C R J Singer, Dr Chris Knechtli, Dr Josephine Crowe, Dr Sarah Wexler; Russells Hall Hospital: Dr C Taylor, Dr D Bareford, Dr J Neilson, Dr S Fernandes; Salford Royal Hospital: Dr JB Houghton, Dr Simon Jowitt, Dr Sonya Ravenscroft; Salisbury District Hospital: Dr Effie Grand, Dr JO Cullis; Sandwell General Hospital: Dr John Gillson; Singleton Hospital: Dr A Benton, Dr H Sati, Dr S Al-Ismail; Southampton General Hospital: Dr D Richardson, Dr K Orchard; Southern General Hospital: Dr AE Morrison; Southport & Formby District General Hospital: Dr Ruhaman Salim; St Bartholomew's Hospital: Dr Heather Oakervee, Dr J Cavenagh, Dr Samir Agrawal; St George's Hospital: Dr F Willis; St Helier Hospital: Dr J Mercieca, Dr M Clarke, Dr R Zuha; St James's University Hospital: Dr BA Mcverry, Dr DT Bowen, Dr GM Smith, Dr Rod Johnson; St Richard's Hospital: Dr Philip C Bevan, Dr S Janes; Staffordshire General Hospital: Dr P Revell; Stirling Royal Infirmary: Dr RF Neilson; Stoke Mandeville Hospital: Dr H Eagleton; The Great Western Hospital: Dr AG Gray, Dr Alex Sternberg, Dr ES Green, Dr NE Blesing; The James Cook University Hospital: Dr Angela Wood, Dr D Plews, Dr R Dang; The Royal Bolton Hospital: Dr J Jip; The Royal Liverpool University Hospital: Dr RE Clark; The Royal Oldham Hospital: Dr Allameddine Allameddine, Dr S Elhanash; The Royal Victoria Infirmary: Dr Anne Lennard, Dr Gail Jones, Dr Graham H Jackson; Torbay District General Hospital: Dr D Turner, Dr Nichola Rymes, Dr P Roberts; Trafford General Hospital: Dr D Alderson; University College Hospital: Dr A Khwaja, Dr K Ardeshna, Dr KG Patterson; University Hospital Aintree: Dr A Olujohungbe, Dr BE Woodcock, Dr R Dasgupta, Dr Ruhaman Salim, Dr W Sadik; University Hospital Coventry (Walsgrave): Dr Anton G Borg, Dr B Harrison, Dr M Narayanan, Dr N Jackson, Dr Shailesh Jobanputra; University Hospital Lewisham: Dr N Mir, Dr T Yeghen; University Hospital Of North Tees: Dr P Mounter; University Hospital Of Wales: Dr C Poynton, Dr C Rowntree, Dr Jonathan Kell, Dr S Knapper, Professor AK Burnett; Victoria Hospital: Dr S Rogers; Victoria Infirmary: Dr P Tansey, Dr RA Sharp; Warwick Hospital: Dr Anton G Borg, Dr Peter E Rose; Western General Hospital: Dr PH Roddie, Dr PRE Johnson; Wexham Park Hospital: Dr N Bienz, Dr PH Mackie, Dr Simon Moule; Whiston Hospital: Dr G Satchi, Dr JA Tappin, Dr Toby Nicholson; Wishaw General Hospital: Dr CL Thomas, Dr Gilla Helenglass; Worcestershire Royal Hospital: Dr AH Sawers, Dr N Pemberton, Dr S Shafeek; Worthing Hospital: Dr AM O'Driscoll; Wycombe General Hospital: Dr J Pattinson, Dr R Aitchison; York Hospital: Dr LR Bond, Dr MR Howard; Ysbyty Glan Clwyd: Dr C Hoyle, Dr Earnest Heartin, Dr MJ Goodrick; Ysbyty Gwynedd District General Hospital: Dr James Seale.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Presented as an oral abstract at the European Haematology Association Annual Meeting June 2015.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Leukemia website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Burnett, A., Russell, N., Hills, R. et al. A comparison of clofarabine with ara-C, each in combination with daunorubicin as induction treatment in older patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia 31, 310–317 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2016.225

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2016.225

This article is cited by

-

Unified classification and risk-stratification in Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Impact of age, functional status, and comorbidities on quality of life and outcomes in elderly patients with AML: review

Annals of Hematology (2021)

-

New Treatment Options for Acute Myeloid Leukemia in 2019

Current Oncology Reports (2019)