Abstract

This article describes a case we experienced in which good postsurgical facial profiles were obtained for a patient with jaw deformities associated with facial asymmetry, by implementing surgical planning with SimPlant OMS. Using this method, we conducted LF1 osteotomy, intraoral vertical ramus osteotomy (IVRO), sagittal split ramus osteotomy (SSRO), mandibular constriction and mandibular border genioplasty. Not only did we obtain a class I occlusal relationship, but the complicated surgery also improved the asymmetry of the frontal view, as well as of the profile view, of the patient. The virtual operation using three-dimensional computed tomography (3D-CT) could be especially useful for the treatment of patients with jaw deformities associated with facial asymmetry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With computer-aided surgical simulation or computer-aided planning, good postsurgical facial features can be expected prior to surgery, such as movement of the jawbone, postsurgical interference with osteotomized segments and movement of soft tissues associated with the mode of the soft tissue simulation. An increasing number of surgeons have applied computer-aided planning to the treatment of jaw deformities, to implantation of prostheses and to the reconstruction of jaw defects.1,2,3,4,5 First, we would like to provide a brief explanation regarding SimPlant OMS software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). Rather than the conventional two-dimensional cephalometric analysis based on frontal and lateral cephalograms, three-dimensional (3D) cephalometric analysis is performed by constructing a three-dimensional computed tomography (3D-CT) image from CT with 1 mm slice imaging. This process is effective in diagnosing cases of asymmetry, as measurements can be obtained separately based on the right and left measuring points.

In cases of patients with jaw deformities, numerous artifacts caused by the inserted orthodontic arch wires can be observed in the areas around the rows of teeth, making it difficult in most cases to determine the precise occlusal relationship using only 3D-CT images.

Therefore, the precise occlusal relationship before and after osteotomy can be determined by incorporating a dental cast into CT with an optical scan wizard, to link the data to 3D-CT images using a virtual occluder.

Evaluating the mode of the soft tissues on 3D-CT images makes it possible to estimate the movement of these tissues before and after osteotomy, such that presurgical and postsurgical facial changes can be simulated by mapping a picture of patients’ facial profiles.

Based on the designed treatment plan, a wafer (surgical splint) can be created using computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing systems. Surgical splints (wafers), in cases of jaw deformity patients or surgical guides, in cases of implant prostheses, can be created.

Case report

The patient was a 26-year-old man who had a class III jaw deformity with a cant occlusal plane cant, along with transverse discrepancy of the maxillary and mandibular dental arch widths (the maxillary width was larger than the mandibular width), associated with an open bite and facial asymmetry. Crowding of the front teeth, an open bite of the front teeth, deviation of the mandibular center to the left, and a left molar crossbite were also observed (Figure 1a–1e).

The presurgical situation. (a–e) The initial records of the patient (pre-orthodontic records). (a, b) The initial facial photographs (a: frontal; b: lateral). (c–e) The initial intraoral photographs (c: right; d: frontal; e: left). (f–j) The presurgical records of the patient (post orthodontic records). (f, g) The presurgical facial photographs (f: frontal; g: lateral). (h–j) The presurgical intraoral photographs (h: right; i: frontal; j: left). (k–m) The presurgical 3D cephalometry (k: right; l: frontal; m: left).

Although the maxillary premolar tooth was extracted, and the alignment of the row of teeth was good in the mandible with no tooth extraction, the transverse discrepancy of the dental arch width had not improved (Figure 1f–1j).

The facial angle between the FH plane (Frankfort plane; Or–Po, Or: Orbitale—the most inferior anterior point on the orbit’s margin, Po: Porion—the most superior point of the external acoustic meatus) and the facial plane (facial plane; N–Pog, N: Nasion—the midpoint of the frontonasal structure—the intersection of the internasal and frontonasal sutures in the midsagittal plane, Pog: Pogonion—the most anterior midpoint of the chin in the midsagittal plane) was larger on the right side, which measured 87.29°, than on the left side, which measured 83.02°. The distance from the FH plane to the maxillary first molar was greater on the right side, which measured 59.57 mm, than on the left side, which measured 55.60 mm; the angle between the facial median line and the occlusal plane was 84°, showing a cant upon counterclockwise rotation.

The median line of the mandible also showed a cant upon counterclockwise rotation (Figure 1k–1m).

Using virtual operations with SimPlant OMS, we performed an LF1 osteotomy: cant and yaw correction on the maxilla; intraoral vertical ramus osteotomy (IVRO) on the right side of the mandible (the side without deviation); sagittal split ramus osteotomy (SSRO) fixed semirigidly with a sliding plate on the left side of the mandible (the side with deviation);6 mandibular constriction (MC);7,8,9 and mandibular border genioplasty (bone removal) in the mental region.10

Cant correction and yaw correction were implemented in the maxilla, while mandibular midline osteotomy was implemented in the mandible to shorten the mandibular width (MC), with a setback of the mandible on the right side and extension of the mandibular ramus height (downward shift) on the left side.

Furthermore, mandibular boarder osteotomy, including genioplasty due to bone removal, was planned for the asymmetry of the mandible angle/mental region that remained after osteotomy.

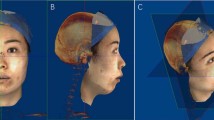

This stage was designed carefully to avoid trismus due to bone inference with the coronoid process and the zygomatic arch (Figure 2a–2c).

It is important to evaluate the case from the lower side of the face in cases of facial asymmetry, in addition to implementing a design such that the left–right asymmetry of the mandibular border, which forms the facial outline, is prevented from moving in this direction (Figure 2d and 2e).

Presurgical and postsurgical facial changes were simulated by mapping a picture of the patient’s facial profiles onto the soft tissue on the 3D-CT images. The asymmetry was improved in the front and lower areas, including the facial profile, following the surgery simulation.

The reduction of the mandibular width was measured, upon confirming the precise occlusal relationship after osteotomy, by optical scanning of the dental cast to link the data to the 3D-CT images.

Cant correction and yaw correction were implemented in the maxilla with a LeFort I osteotomy, and the right molar tooth was impacted in the upper area, resulting in complete down fracture, while Piezo Surgery (Mectron, Carasco, Italy) was applied for bone removal in the area surrounding the descending palatine artery.

MC was implemented using two lag screws, following a mandibular midline osteotomy.

Setback of the mandible with IVRO was performed on the right side of the mandible, and extension of the mandibular ramus height (downward shift) with SSRO was performed by semirigid fixation, using the sliding plate and one additional screw fixation on the left side of the mandible.

Furthermore, bone removal in the distorted position was applied to the asymmetry in the mental region that remained following osteotomy (Figure 3a and 3b). The seating of the condyles was good postoperatively.

Postsurgical X-ray images and pre- and postsurgical cephalometric analyses. (a, b) Postsurgical X-ray images (a: frontal cephalogram; b: panoramic). (c) The presurgical and postsurgical frontal cephalotraces (left: transferred 3D-CT image; right: cephalometric X-ray image). (d) The distance from the FH plane to the upper first molars (left-blue: presurgical frontal cephalotrace; right-red: postsurgical frontal cephalotrace). (e) The dental arch width of the maxilla and mandible (the distance between the first molars) (left-blue: presurgical frontal cephalotrace; right-red: postsurgical frontal cephalotrace). (f) The positional relationship between the right and left mandibular angles and the facial midline (left-blue: presurgical frontal cephalotrace; right-red: postsurgical frontal cephalotrace). (g) The superimpositions of the presurgical/postsurgical frontal cephalotraces (blue: presurgical; red: postsurgical; orange: the postsurgical mirror image of the half on the right side onto the other side). (h) The superimpositions of the presurgical/postsurgical frontal cephalotraces showing the CRs of the occlusal plane and the median mandible (blue: presurgical; red: postsurgical). (I) The superimposition of the lateral cephalotrace. C: cant correction; 3D-CT, three-dimensional computed tomography; CR, clockwise rotation; IV: intraoral vertical ramus osteotomy; M: MC/mandibular constriction; L1, L2: lag screws; R: mandibular border osteotomy (bone removal); Sc: screw fixation; Sp: sliding plate fixation (semirigid); SS: sagittal split ramus osteotomy; Y: yaw correction.

With regard to the presurgical and postsurgical evaluations of the frontal cephalogram, as no precise superimposition was possible due to the discordance of the upper and lower slant (rolling) of the face on the frontal cephalogram, an evaluation was undertaken by rotationally transferring the presurgical 3D-CT image to the location matching the postsurgical frontal cephalometric X-ray image (Figure 3c).

Although the distance from the FH plane to the upper first molar was greater on the right side prior to surgery, the postsurgical distance was improved and was almost equal on both sides (Figure 3d).

With regard to the dental arch widths of the maxilla and mandible (the distance between the first molars), although the width of the mandible was greater than that of the maxilla presurgically, that of the mandible was improved to create a normal relationship (the maxillary width is larger than the mandibular width) postsurgically (Figure 3e).

Regarding the positional relationship between the right and left mandibular angles and the facial midline, although the positional relationship between the right and left mandibular angles was larger on the left side than the right side presurgically, the postsurgical location was improved to being almost equal on both sides. Furthermore, the total was shortened from 114 mm to 105 mm. The presurgical intersecting degree of 95° was improved to a perpendicular angle of 90° postsurgically (Figure 3f).

Subsequently, with regard to the positional relationship between the right and left mandibular angles and the mandibular midline, although the right side was larger presurgically, it was improved to being almost equal on both sides postsurgically. The presurgical intersecting degree of 86° was improved to a perpendicular angle of 89° postsurgically.

The superimpositions of the presurgical–postsurgical frontal cephalotraces are shown in Figure 3g. Upon superimposing the postsurgical mirror image of the half on the right side onto the other side (orange), it was confirmed that the postsurgical image (red) was close to bilateral symmetry (Figure 3g).

The summary of the results regarding the presurgical and postsurgical frontal cephalograms is shown in Table 1. The occlusal plane measured 9°, while the median mandible measured 14° upon CR (clockwise rotation) (Figure 3h).

The superimposition of the lateral cephalotrace is shown in Figure 3i (Table 2). It improved from class III to class I.

The splint was removed 1 month after surgery and was replaced with occlusal guidance, using only intermaxillary elastics.

The facial pictures 3 months after surgery confirmed that the asymmetry in the frontal view, as well as the profile view, was improved. The asymmetry was nearly in accordance with soft-tissue simulation (Figure 4a–4h). Furthermore, even in the upward view, left-right symmetry was almost obtained, similar to the soft tissue simulation (Figure 4d and 4h).

The postsurgical situation. (a–l) Three-month postsurgical situation. (a–d) Soft tissue simulated images (a: frontal; b: from the diagonal angle/right side; c: lateral/right side; d: from the bottom side). (e–h) Three-month postsurgical facial photographs (e: frontal; f: from the diagonal angle/right side; g: lateral/right side; h: from the bottom side). (i–k) Three-month postsurgical intraoral photographs (i: right; j: frontal; k: left). (l) Three-month postsurgical panoramic X-ray image. (m–s) One year and six months postsurgery situation. (m–o) One year and six months postsurgery facial photographs (m: frontal; n: from the diagonal angle/right side; o: lateral/right side). (p–r) One year and six months postsurgery intraoral photographs (o: right; p: frontal; q: left). (s) One year and six months postsurgery panoramic X-ray image.

The intraoral photographs 3 months after surgery showed the accordance of the median of the maxilla and mandible, obtaining a class I occlusal relationship (Figure 4i–4k).

It was confirmed that the seating of the mandibular head was well maintained even 3 months after surgery, resulting from the reduction in interference with the osteotomized segments, as a result of the surgery to reduce the mandibular width (MC) (Figure 4l).

The facial pictures and intraoral photographs 1 year and 6 months after surgery confirmed that the improved soft tissue symmetry in the frontal view, the profile view, the class I occlusal relationship without an open bite, the accordance of the median of the maxilla and mandible and the right temporomandibular joint seating without temporomandibular joint symptoms were maintained (Figure 4m–4s).

Discussion

Surgical planning using computer-aided planning made it possible to obtained measurements from various directions. Compared to conventional surgery planning combining a two-dimensional cephalo and model surgery that only pursued occlusion, harmonious overall maxillofacial surgery planning was facilitated.

As shown in this case, relocation of bone chips to ensure symmetry in the hard tissue (bone) did not necessarily leave the face of the soft tissue symmetrical accordingly.

Hence, to obtain a good (symmetrical) postoperative face in asymmetric cases, evaluation in the soft tissue mode by surgery planning was apparently crucial.11

With other treatment plans, enlargement of the maxillary bone width by surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion12,13,14 and extension of the vertical dimension of the mandibular ramus using distraction osteogenesis of the mandible15,16 are contemplated. In any case, these techniques require an oral appliance to be worn over the long term, in addition to rendering postoperative occlusal adjustment and orthodontic treatment more difficult.

Implementing surgical planning, using computer-aided planning, was useful in terms of obtaining informed consent from patients, sharing information among orthodontists, and understanding the surgical team’s surgical forms.

Using virtual operations, not only was free designing possible, but it was also possible to predict matters such as the inference of immovable osteotomized segments. As shown in this case, it was possible to realize complicated surgical planning, including the prevention of interference with osteotomized segments (between the distal and proximal mandibular segments) due to the reduction of the mandibular width, the first-stage extension of the mandibular ramus height and bone removal for asymmetry after movement of the jawbones.

In conclusion, virtual operations using 3D-CT were especially useful for the treatment of patients with jaw deformities associated with facial asymmetry.

References

Baker SB, Goldstein JA, Seruya M . Outcomes in computer-assisted surgical simulation for orthognathic surgery. J Craniofac Surg 2012; 23( 2): 509–513.

Zhao LP, Patel PK, Cohen M . Application of virtual surgical planning with computer assisted design and manufacturing technology to cranio-maxillofacial surgery. Arch Plast Surg 2012; 39( 4): 309–316.

van der Meer WJ, Bos RR, Vissink A et al. Digital planning of cranial implants. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012; 51( 5): 450–452.

Giordano M, Ausiello P, Martorelli M et al. Reliability of computer designed surgical guides in six implant rehabilitations with two years follow-up. Dent Mater 2012; 28( 9): e168–e177.

Foley BD, Thayer WP, Honeybrook A et al. Mandibular reconstruction using computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing: an analysis of surgical results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012; 71( 2): e111–e119.

Ghang MH, Kim HM, You JY et al. Three-dimensional mandibular change after sagittal split ramus osteotomy with a semirigid sliding plate system for fixation of a mandibular setback surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2013; 115( 2): 157–166.

Joondeph DR, Bloomquist D . Mandibular midline osteotomy for constriction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2004; 126( 3): 268–270.

Alexander CD, Bloomquist DS, Wallen TR . Stability of mandibular constriction with a symphyseal osteotomy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1993; 103( 1): 15–23.

Bloomquist D . Mandibular narrowing: advantage in transverse problems. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004; 62( 3): 365–368.

Zhang Z, Tang R, Tang X et al. The oblique mandibular chin-body osteotomy for the correction of broad chin. Ann Plast Surg 2010; 65( 6): 541–545.

Choi JY, Lee SH, Baek SH . Effects of facial hard tissue surgery on facial aesthetics: changes in facial content and frames. J Craniofac Surg 2012; 23( 6): 1683–1686.

Magnusson A, Bjerklin K, Kim H et al. Three-dimensional assessment of transverse skeletal changes after surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion and orthodontic treatment: a prospective computerized tomography study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2012; 142( 6): 825–833.

Pereira MD, de Abreu RA, Prado GP et al. Strategies for surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion according to the region of transverse maxillary deficiency. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012; 41( 9): 1127–1130.

Goddard R, Witherow H . Surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion (SARPE). Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011; 49( 1): 65–66.

Sun H, Li B, Zhao Z et al. Error analysis of a CAD/CAM method for unidirectional mandibular distraction osteogenesis in the treatment of hemifacial microsomia. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013; pii: S0266-4356(13)00084-3. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.02.012. [ Epub ahead of print].

Al-Mahdi AH, Al-Jumaily HA . Clinical evaluation of distraction osteogenesis in the treatment of mandibular hypoplasia. J Craniofac Surg 2013; 24( 1): e50–e57.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hara, S., Mitsugi, M., Kanno, T. et al. Three-dimensional virtual operations can facilitate complicated surgical planning for the treatment of patients with jaw deformities associated with facial asymmetry: a case report. Int J Oral Sci 5, 176–182 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2013.48

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2013.48

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Selection of a horizontal reference plane in 3D evaluation: Identifying facial asymmetry and occlusal cant in orthognathic surgery planning

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Computer aided planning of orthopaedic surgeries: the definition of generic planning steps for bone removal procedures

International Orthopaedics (2017)