Abstract

Acute hypertension is associated with hematoma enlargement and poor clinical outcomes in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). However, the method of controlling blood pressure (BP) during the acute phase of ICH remains unknown. The aim of this study is to show current strategies about this issue in Japan. Questionnaires regarding antihypertensive treatment (AHT) strategies were sent to neurosurgeons, neurologists and others responsible for ICH management in 1424 hospitals. Of 600 respondents, 550 (92%) worked at hospitals wherein acute ICH patients are managed and 548 (99.6%) of them agreed with the application of AHT within 24 h of ICH onset. Most answered that the systolic BP threshold for starting AHT was 180 mm Hg (36%) or 160 mm Hg (31%), which differed significantly between neurosurgeons (median, 160 mm Hg) and neurologists/others (180 mm Hg, P<0.001). The goal of lowering systolic BP was to reach a maximum of 140, 150 or 160 mm Hg according to 448 respondents (82%) and 209 (38%) intensively lowered systolic BP to ⩽140 mm Hg. Nicardipine was the first choice of intravenous drug for 313 (57%) and the second choice for 146 respondents (27%). However, 141 (26%) thought that nicardipine is inappropriate mainly because of a conflict with a description of contraindications on the official Japanese label for this drug. In conclusion, the present Japanese respondents, especially neurosurgeons, lower BP more aggressively than recommended in domestic and Western guidelines for managing acute ICH patients. Nicardipine was the most frequent choice of antihypertensive agent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is not only life threatening but also causes major disability. The annual incidence of ICH in Japan is several-fold higher than that in Caucasian populations.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Chronic hypertension is a leading risk factor for ICH2, 6, 7 and such patients often have high blood pressure (BP) on admission. Acute high BP might enhance active intracranial bleeding and hematoma growth, which could be a determinant of poor clinical outcome.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 In contrast, some investigators insist that high BP might work to maintain normal cerebral blood flow and prevent peri-hematomal ischemic damage.13, 14 However, pharmacologically mediated BP reduction apparently has no adverse effects on cerebral blood flow in humans or other animals.15, 16 Control of BP for acute ICH remains controversial.

American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guidelines17 and the Japanese Guidelines for the Management of Stroke 200418 both recommend lowering of BP for ICH patients with systolic blood pressure (SBP) of >180 mm Hg or mean arterial pressure of >130 mm Hg. The target BP level has not been defined. The European Stroke Initiative (EUSI) advocates an upper recommended limit of 180/105 mm Hg and a target BP of 160/100 mm Hg for acute ICH patients with known earlier hypertension or signs of chronic hypertension.19 However, these recommendations are based on limited information and neither their usefulness nor their effects are well established.

Another concern regarding the lowering of BP in acute ICH patients is of the differences in recommendations for intravenous (i.v.) antihypertensive drugs among guidelines. Both the AHA/ASA and the EUSI guidelines recommend i.v. administration of the adrenergic inhibitors, labetalol and esmolol, and of the calcium channel blocker, nicardipine. In Japan, labetalol is not approved for commercial use, esmolol is used only for antiarrhythmia, and nicardipine administration for hyperacute ICH patients is limited by the description on the official label.

To conform to worldwide trends, BP control in ICH patients in Japan should be standardized, domestic recommendations that differ from others should be reconsidered, and an active role in international trials should be taken. Therefore, we conducted a nationwide web survey as the first step toward defining current standard strategies of BP control in Japanese patients with acute ICH.

Methods

We surveyed 1424 certified training institutes recommended by the Japan Stroke Society, the Japan Neurosurgical Society and the Societas Neurologica Japonica. Web questionnaires (https://ssl.e-ult.jp/ICH/, for limited members) regarding acute ICH management and antihypertensive treatment (AHT) strategies were sent to hospital directors in July 2008 with a request that they encourage responsible physicians involved in stroke management to reply by September 2008.

The inquiry started by questioning whether acute ICH patients are usually treated in the respondents’ hospitals. Those who responded affirmatively were required to answer seven questions about conditions surrounding acute ICH management and 14 questions about AHT for acute ICH (Table 1). When respondents disagreed with AHT for acute ICH patients in Question 10 (Q10), responses to subsequent questions were not required. All answers were multiple choice, except for Questions 2, 5 and 9, which required integral numbers.

At the end of the survey, we asked if the respondents were interested in further inquiries. Those who answered in the affirmative received a supplementary questionnaire in October 2008 to determine whether their patients experienced side effects of i.v. antihypertensive drugs during acute ICH management. Respondents were only required to e-mail a reply to this simple question if they recognized possible side effects.

Statistics

The BP thresholds in Questions 12, 13 and 21 were compared between neurosurgeons and respondents from other specialties using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to represent a significant difference.

Results

Among a total of 602 collected responses, two were excluded from the analyses because the same respondents answered twice, leaving 600 responses remaining from 1424 (42.1%) hospitals. Of these, 50 replied that they did not usually treat patients with acute ICH at their hospitals. Finally, 550 responses (38.6% of 1424 hospitals) were analyzed.

Conditions for acute ICH management

Of the 550 respondents, 457 (83.1%) were neurosurgeons (Q1; Table 2). Overall, the respondents had spent a median of 23 years in clinical medicine (Q2). The median number of ICH patients treated annually ranged between 41 and 60 (Q3). The main department for ICH management was neurosurgery (79.5%), whereas 10.5% of respondents replied that a mixed team from neurosurgery and neurology treated patients with acute ICH (Q4). The median number of ICH attending physicians was three per hospital (Q5). An ICU (intensive care unit) was the main ward (34.5%), and a SCU (stroke care unit) was used in only 12.7% of the respondent hospitals (Q6). The availability of doctors responsible for initial management of emergency ICH patients in the respondent hospitals or on call 24/7 was 61.6% (Q7).

Antihypertensive treatment for acute ICH

Blood pressure was measured during acute ICH mainly using automated equipment (81.3%, Q8; Table 2). The median number of BP measurements was 24 during the initial 24 h (Q9). Two respondents (0.4%) replied that AHT should not be performed within 24 h of ICH onset and the other 548 agreed with AHT (Q10). Thus, we analyzed the following results from these 548 respondents.

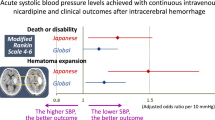

Antihypertensive treatment was started mostly in the emergency room or in the CT/MRI room immediately after a diagnosis of ICH was confirmed (85.0%, Q11). The threshold median SBP level for AHT initiation was 160 mm Hg (interquartile range: (IQR) 150–180 mm Hg), with biphasic peaks at 180 mm Hg (35.6%) and 160 mm Hg (30.8%, Q12; Figure 1, top). The median levels differed between neurosurgeons (160 mm Hg (IQR: 150–180)) and other physicians (180 mm Hg (160–180), P<0.001). Guideline-based initiation for patients with SBP ⩾180 mm Hg was approved by 40.0% of the overall respondents, 35.3% of neurosurgeons and 63.0% of the remainder.

Answers to Questions 12, 13 and 21. Top: Threshold systolic blood pressure (SBP) required to start antihypertensive treatment (AHT). Middle: SBP during hyperacute stage by intravenous AHT. Bottom: SBP during chronic stage targeted by oral AHT. DBP: diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) used by respondents rather than SBP as threshold or target value.

The target of lowering the SBP was also biphasic at 160 mm Hg (29.4%) and 140 mm Hg (29.7%); 448 respondents (81.8%) approved 140, 150 or 160 mm Hg as the target (Q13; Figure 1, middle). The median (IQR) target levels of neurosurgeons were 150 (140–160) mm Hg and those of others were 160 (150–170) mm Hg (P<0.001). Intensive lowering to ⩽140 mm Hg was approved by 38.1% of the overall respondents, 41.0% of neurosurgeons and 23.9% of the remainder.

The most frequent first choice of i.v. drug was nicardipine (57.1%), followed by diltiazem (34.9%, Q14). The main reason for administering nicardipine was its ability to lower BP (96.2%, Q15). The second choice of respondents (26.5%) was nicardipine (Q16). Thus, nicardipine was used for acute ICH patients as the first or second choice by 83.5% of respondents, and by 396 (86.8%) neurosurgeons and 63 (68.5%) other respondents (P=0.14). Although 266 (48.4%) respondents answered that any i.v. drugs that lower BP are appropriate for patients with acute ICH, 141 (25.6%) replied that nicardipine is inappropriate, mainly because of the contraindications described on the label (90.1%, Q17, Q18). Around half of the respondents replied that active intracranial bleeding ceases within 6 h (50.5%, Q19).

After i.v. AHT, 360 respondents (65.5%) administer oral AHT using a calcium channel blocker, followed by an angiotensin II receptor blocker (30.0%, Q20). The target SBP value of 333 respondents (60.5%) was ⩽140 mm Hg (Q21). The median (IQR) target values of neurosurgeons were 140 (140–140) mm Hg and those of other physicians were 140 (130–140) mm Hg (P=0.001).

Supplementary inquiry

Among the respondents to the initial web questionnaire, 414 (75.3%) expressed an interest in further inquiries. We sent them another questionnaire to determine whether their patients experienced any possible side effects of i.v. antihypertensive drugs. A total of 32 physicians responded. Of them, 18 had patients who experienced bradycardia or atrioventricular block and one had a patient who developed arrhythmia during diltiazem administration. Nicardipine caused phlebitis (n=6), tachycardia (n=3) and liver dysfunction (n=2). One respondent described a decrease of oxygen partial pressure in arterial blood in a patient receiving nitroglycerin. A total of 10 respondents replied that i.v. drug administration did not cause side effects.

Discussion

This study shows the current strategies regarding AHT for acute ICH patients in Japan. The first major finding was that 60% of the respondents start AHT on the basis of a threshold SBP level that is lower than that recommended by guidelines (180 mm Hg). The second major finding was that 80% of the respondents lowered SBP to a maximum of 140, 150 or 160 mm Hg, and 40% intensively lowered SBP to ⩽140 mm Hg. These two findings mainly reflect the opinions of neurosurgeons, as they accounted for 80% of the respondents. Both the threshold SBP level required to initiate AHT and the target SBP level were higher according to responses from other physicians (mainly neurologists and vascular neurologists) compared with those from neurosurgeons. The third major finding was that nicardipine is the most effective i.v. drug to reduce BP of patients with acute ICH, although such usage conflicts with the official Japanese label.

The threshold SBP level required to initiate AHT and the target SBP level recommended in the guidelines are not identical and are not based on sophisticated trials; over half of the respondents set lower values for these two parameters than those recommended by the AHA/ASA guidelines. The present findings indicate that most Japanese neurosurgeons prefer stricter AHT for ICH patients than that recommended by the current guidelines. This tendency might be because a stricter AHT than the usual one is recommended when surgical therapy is scheduled for ICH in Japanese guidelines, although the evidence level is not high.20 A lower target SBP than the guidelines recommend has been reported recently. Ohwaki et al.20 assessed 76 patients with ICH and found that an SBP target of ⩽150 mm Hg was less significantly associated with hematoma growth than that of ⩾160 mm Hg. Our observational study of 244 patients with ICH showed that lowering SBP to <138 mm Hg during the initial 24 h after admission seems to predict a favorable early outcome.21 Two major clinical trials are ongoing to determine the safety and efficacy of intensively lowering BP for acute ICH: the Intensive Blood Pressure Reduction in Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage Trial (INTERACT)22 and the Antihypertensive Treatment of Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage (ATACH).23 The vanguard phase of INTERACT showed that early intensive lowering of BP with a targeted SBP of 140 mm Hg and careful monitoring was feasible, safe and might have modestly attenuated hematoma growth in 346 randomized patients in the standard best practice stroke unit care.22 Phase I of ATACH investigated the potential consequences of controlling BP with i.v. nicardipine at the sequential levels of 170–200, 140–170 and 110–140 mm Hg in 60 patients.23 The result was announced in a recent conference.22

This survey clarified a contradiction regarding the prevalence of nicardipine administration to Japanese patients with ICH regardless of the following contraindications described on the official label; ‘nicardipine is contraindicated for (I) ICH patients with a suspicion of ongoing intracranial bleeding not to enhance bleeding and for (II) acute stroke patients with elevated intracranial pressure not to accelerate intracranial pressure elevation.’ When nicardipine was originally approved for commercial use as an ameliorant of cerebral circulation, not as an antihypertensive agent, in Japan in 1981, a description of the above contraindications was listed on the label following that of another ameliorant of cerebral circulation. As far as we can determine, the limited administration of nicardipine for patients with ongoing intracranial bleeding or high intracranial pressure is not supported by any scientific evidence. The description on the label has another problem in that the time when active intracranial bleeding ceases is not as clear as stated in the answer to Q19. On the basis of the results of this survey, a formal request for reassessment of the official label of nicardipine was submitted to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan by the Japan Stroke Society, Japan Neurosurgical Society and the Japanese Society of Hypertension in October 2008. Diltiazem was the second most frequently administered drug, which seems to be associated with an influence on cardiac rhythms. On the basis of Japanese official labels, nitroglycerin is not administered to lower BP except for patients with acute heart failure, unstable angina or perioperative conditions, and nitroprusside is limited to patients with severely damaged cerebral circulation. A limitation of this study was that we did not ask in the web questionnaires whether respondents know the contraindication of nicardipine listed on the official label. It is important to know how many doctors use nicardipine with or without knowing this contraindication.

Calcium channel blockers and angiotensin II receptor blockers were the choices of oral antihypertensive drugs after i.v. administration in 65.5 and 30.0% of respondents, respectively. The most frequent target SBP according to our respondents (140 mm Hg) was identical to the level recommended by the guidelines of the Japanese Society of Hypertension23 and higher than that in the guidelines from the European Society of Hypertension and European Society of Cardiology (130 mm Hg).24

In conclusion, current Japanese strategies based on this survey regarding acute BP lowering for ICH patients, especially by neurosurgeons, differ considerably from strategies recommended in various guidelines. We are planning to conduct a multicenter, randomized clinical trial of Japanese patients with ICH to determine the optimal BP target of AHT based on the results of this survey.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Broderick JP, Brott T, Tomsick T, Huster G, Miller R . The risk of subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhages in blacks as compared with whites. N Engl J Med 1992; 326: 733–736.

Furlan AJ, Whisnant JP, Elveback LR . The decreasing incidence of primary intracerebral hemorrhage: a population study. Ann Neurol 1979; 5: 367–373.

Drury I, Whisnant JP, Garraway WM . Primary intracerebral hemorrhage: impact of CT on incidence. Neurology 1984; 34: 653–657.

Brott T, Thalinger K, Hertzberg V . Hypertension as a risk factor for spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 1986; 17: 1078–1083.

Schutz H, Bodeker RH, Damian M, Krack P, Dorndorf W . Age-related spontaneous intracerebral hematoma in a German community. Stroke 1990; 21: 1412–1418.

Mohr JP, Caplan LR, Melski JW, Goldstein RJ, Duncan GW, Kistler JP, Pessin MS, Bleich HL . The Harvard Cooperative Stroke Registry: a prospective registry. Neurology 1978; 28: 754–762.

Qureshi AI, Suri MA, Safdar K, Ottenlips JR, Janssen RS, Frankel MR . Intracerebral hemorrhage in blacks. Risk factors, subtypes, and outcome. Stroke 1997; 28: 961–964.

Carlberg B, Asplund K, Hagg E . The prognostic value of admission blood pressure in patients with acute stroke. Stroke 1993; 24: 1372–1375.

Britton M, Carlsson A, de Faire U . Blood pressure course in patients with acute stroke and matched controls. Stroke 1986; 17: 861–864.

Fogelholm R, Avikainen S, Murros K . Prognostic value and determinants of first-day mean arterial pressure in spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 1997; 28: 1396–1400.

Terayama Y, Tanahashi N, Fukuuchi Y, Gotoh F . Prognostic value of admission blood pressure in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Keio Cooperative Stroke Study. Stroke 1997; 28: 1185–1188.

Kazui S, Minematsu K, Yamamoto H, Sawada T, Yamaguchi T . Predisposing factors to enlargement of spontaneous intracerebral hematoma. Stroke 1997; 28: 2370–2375.

Kuwata N, Kuroda K, Funayama M, Sato N, Kubo N, Ogawa A . Dysautoregulation in patients with hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage. A SPECT study. Neurosurg Rev 1995; 18: 237–245.

Qureshi AI, Bliwise DL, Bliwise NG, Akbar MS, Uzen G, Frankel MR . Rate of 24-h blood pressure decline and mortality after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a retrospective analysis with a random effects regression model. Crit Care Med 1999; 27: 480–485.

Qureshi AI, Wilson DA, Hanley DF, Traystman RJ . Pharmacologic reduction of mean arterial pressure does not adversely affect regional cerebral blood flow and intracranial pressure in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care Med 1999; 27: 965–971.

Powers WJ, Zazulia AR, Videen TO, Adams RE, Yundt KD, Aiyagari V, Grubb Jr RL, Diringer MN . Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow surrounding acute (6–22 h) intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 2001; 57: 18–24.

Broderick J, Connolly S, Feldmann E, Hanley D, Kase C, Krieger D, Mayberg M, Morgenstern L, Ogilvy CS, Vespa P, Zuccarello M . Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in adults: 2007 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, High Blood Pressure Research Council, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Stroke 2007; 38: 2001–2023.

Shinohara Y, Yamaguchi T . Outline of the Japanese Guidelines for the Management of Stroke 2004 and subsequent revision. Int J Stroke 2008; 3: 55–62.

Steiner T, Kaste M, Forsting M, Mendelow D, Kwiecinski H, Szikora I, Juvela S, Marchel A, Chapot R, Cognard C, Unterberg A, Hacke W . Recommendations for the management of intracranial haemorrhage—part I: spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. The European Stroke Initiative Writing Committee and the Writing Committee for the EUSI Executive Committee. Cerebrovasc Dis 2006; 22: 294–316.

Ohwaki K, Yano E, Nagashima H, Hirata M, Nakagomi T, Tamura A . Blood pressure management in acute intracerebral hemorrhage: relationship between elevated blood pressure and hematoma enlargement. Stroke 2004; 35: 1364–1367.

Itabashi R, Toyoda K, Yasaka M, Kuwashiro T, Nakagaki H, Miyashita F, Okada Y, Naritomi H, Minematsu K . The impact of hyperacute blood pressure lowering on the early clinical outcome following intracerebral hemorrhage. J Hypertens 2008; 26: 2016–2021.

Qureshi AI, Qureshi Z, Palesch YY . Antihypertensive Treatment of Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage (ATACH) trial: final results. Stroke 2009; 40: e111 (abstract).

Ogihara T, Kikuchi K, Matsuoka H, Fujita T, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, Imai Y, Imaizumi T, Ito S, Iwao H, Kario K, Kawano Y, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Kimura G, Matsubara H, Matsuura H, Naruse M, Saito I, Shimada K, Shimamoto K, Suzuki H, Takishita S, Tanahashi N, Tsuchihashi T, Uchiyama M, Ueda S, Ueshima H, Umemura S, Ishimitsu T, Rakugi H, on behalf of The Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2009). Hypertens Res 2009; 32: 3–107.

Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, Grassi G, Heagerty AM, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Narkiewicz K, Ruilope L, Rynkiewicz A, Schmieder RE, Boudier HA, Zanchetti A, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Erdine S, Kiowski W, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Lindholm LH, Viigimaa M, Adamopoulos S, Bertomeu V, Clement D, Farsang C, Gaita D, Lip G, Mallion JM, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, O’Brien E, Ponikowski P, Redon J, Ruschitzka F, Tamargo J, van Zwieten P, Waeber B, Williams B . 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2007; 25: 1105–1187.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid (H20-Junkanki-Ippan-019, chief investigator: Kazunori Toyoda, MD) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Koga, M., Toyoda, K., Naganuma, M. et al. Nationwide survey of antihypertensive treatment for acute intracerebral hemorrhage in Japan. Hypertens Res 32, 759–764 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2009.93

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2009.93

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Controlling blood pressure soon after intracerebral hemorrhage: The SAMURAI-ICH Study and its successors

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2019)

Hypertension Research (2019)

-

Chapter 6. Hypertension associated with organ damage

Hypertension Research (2014)