Abstract

Purpose:

The cytosolic enzyme N-glycanase 1, encoded by NGLY1, catalyzes cleavage of the β-aspartyl glycosylamine bond of N-linked glycoproteins, releasing intact N-glycans from proteins bound for degradation. In this study, we describe the clinical spectrum of NGLY1 deficiency (NGLY1-CDDG).

Methods:

Prospective natural history protocol.

Results:

In 12 individuals ages 2 to 21 years with confirmed, biallelic, pathogenic NGLY1 mutations, we identified previously unreported clinical features, including optic atrophy and retinal pigmentary changes/cone dystrophy, delayed bone age, joint hypermobility, and lower than predicted resting energy expenditure. Novel laboratory findings include low cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) total protein and albumin and unusually high antibody titers toward rubella and/or rubeola following vaccination. We also confirmed and further quantified previously reported findings noting that decreased tear production, transient transaminitis, small feet, a complex hyperkinetic movement disorder, and varying degrees of global developmental delay with relatively preserved socialization are the most consistent features.

Conclusion:

Our prospective phenotyping expands the clinical spectrum of NGLY1-CDDG, offers prognostic information, and provides baseline data for evaluating therapeutic interventions.

Genet Med 19 2, 160–168.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDGs) are a group of inborn errors characterized by abnormalities in the process of glycosylation of biomolecules.1,2,3 Although more than 100 different CDGs have been reported since the first description by Jaeken et al. in 1980 (refs. 4,5,6,7), only one congenital disorder of deglycosylation has been described. NGLY1 deficiency (OMIM 610661 and 615273), or NGLY1-CDDG, was first reported in 2012 by Need et al.,8 who, through exome sequencing, identified biallelic mutations in the NGLY1 gene as the cause of disease in one child.

NGLY1 encodes N-glycanase 1, an enzyme involved in the cytosolic degradation of misfolded glycoproteins and other glycoproteins bound for degradation.9 In the index case, a 3-year-old boy inherited a maternal c.1891delC (p.Q631S NM_018297.3) variant and a paternal c.1201A>T (p.R401* NM_018297.3) variant. NGLY1 protein expression in leukocytes was reduced in the parents and undetectable in the proband compared with controls. Transferrin isoelectric focusing and N-glycan profiling were normal, accounting for the difficulty in ascertaining other affected individuals.8 However, a social media campaign linked seven additional affected individuals.10 In 2014, Enns et al.11 published a retrospective chart review highlighting the most common findings in the eight known NGLY1-CDDG patients. At the same time, we initiated a natural history study of the disorder at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center (http://clinicaltrials.gov, trials NCT00369421 and NCT02089789); this report documents the results of comprehensive, prospective, clinical, molecular, radiologic, and laboratory investigations performed for 12 affected individuals.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The families were enrolled in NIH protocols 76-HG-0238 “Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients With Inborn Errors of Metabolism or Other Genetic Disorders” (http://clinicaltrials.gov, trial NCT00369421) and 14-HG-0071 “Clinical and Basic Investigations Into Known and Suspected Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation” (http://clinicaltrials.gov, trial NCT02089789), which were approved by the National Human Genome Research Institute’s institutional review board. The parents gave written informed consent for their children and dependents. Consent forms allowing publication of full-face and body photographs and videos were also obtained. Medical records were collected and reviewed, and each subject was admitted to the NIH Clinical Center for a 4- to 15-day evaluation.

Clinical studies

Clinical studies were designed to detail the phenotypic features of NGLY1-CDDG. Blood, urine, cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), lymphoblasts, and primary dermal fibroblasts were collected, analyzed, and stored. Studies included brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) (Supplementary Methods online), routine and overnight electroencephalograms (EEGs) with a limited montage performed during a sleep study, electromyogram (Supplementary Methods online) and nerve conduction studies (Supplementary Methods online), indirect calorimetry, awake and sedated eye examination with Schirmer II testing, optical coherence tomography scans and electroretinography, behavioral determination of pure tone thresholds, tympanometry, distortion product otoacoustic emissions, auditory brainstem-evoked potentials (ABR), quantitative sweat analysis autonomic testing (QSWEAT) (Supplementary Methods online), gastric aspiration, swallow study, skeletal survey, bone age, dual X-ray absorptiometry, abdominal ultrasound, vibration-controlled transient elastography (Fibroscan),12 echocardiogram, and electrocardiogram. Consultations included clinical neurology, audiology, nutrition, ophthalmology, hepatology, growth, puberty and hormonal studies, allergy and immunology, genetic counseling, physiatry, and speech, occupational, and physical therapy. Eleven individuals underwent developmental psychological evaluations consisting of at least the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (second edition).13 Cognitive function was assessed with testing specific for age and developmental level that provided either an intelligence quotient (IQ) or a developmental quotient score. In addition, the Nijmegen pediatric CDG rating scale, a measure of clinical disease progression developed for CDG, was applied to all affected individuals younger than 18 years.14

Results

Molecular findings

Twelve individuals from 10 families with confirmed biallelic mutations in NGLY1 were admitted to the NIH Clinical Center. Subjects 3 and 11 are siblings, and subjects 7 and 8 are siblings. Six individuals (patients 2, 3, 6, 9, 11, and 12) were included in previous clinical publications.11,15,16 All individuals (six female; six male) were white and ranged from 2.5 to 21.3 years of age. We identified 13 mutations: 5 missense mutations, 5 nonsense mutations, 2 splice-site mutations, and 1 frameshift mutation ( Table 1 ). The most common mutation was c.1201A>T (p.R401*), occurring in seven alleles. The mutations were widely dispersed along the gene with no obvious hotspot.17 Only four of the mutations lay within the catalytic domain ( Figure 1 ). Family histories are detailed in the Supplementary Materials and Methods online.

Distribution of NGLY1 mutations. Shaded bars are exons. Previously unreported mutations include c.953T>C, c.1169G>C, c.1604G>A, and c.1910delT. Mutations previously published and not in this article include c.1624C>T (exon 11), c.1205_1207delGAA (exon 8), and c.1533_1536delTCAA (exon 10). Four mutations lie within the catalytic domain (amino acid residues 292–353), i.e., c.730T>C, c.953T>C, c.931G>A, and c.930C>T. The accession numbers for the NM_018297.3:c.931G>A, NM_018297.3:c.1604G>A, NM_018297.3:c.622C>T, NM_018297.3:c.347C>G, NM_018297.3:c.1169G>C, NM_018297.3:c.730T>C, NM_018297.3:c.1910delT, NM_018297.3:c.930C>T, and NM_018297.3:c.881+5G>T sequences reported in this article are (clinVar) as follows: SCV000259179, SCV000259180, SCV000259181, SCV000259182, SCV000259183, SCV000259184, SCV000259185, SCV000259186, and SCV000259187, respectively.

Dysmorphology

Most affected individuals had hypotonic facies. The features of older individuals reflected their low weight, with thin facies, hollowed cheeks, and visible zygomatic arches. Eye measurements, performed for 10 subjects, varied greatly and revealed no consistent abnormality ( Figure 2 ).

Facial features of NGLY1-CDDG. Individuals with NGLY1-CDDG are arranged from youngest (top left) to oldest (bottom right). Facial features include upturned nasal tip, hypotonic facies, ptosis, brachycephaly, thinned facies, hollowed cheeks, and visible zygomatic arches. Interpupillary distance ranged from the 13th to 95th percentiles, with the mean at the 66th percentile and SEM of 8. Horizontal fissure length ranged from the 3rd to 70th percentiles, with mean at the 20th percentile and SEM of 1. Inner canthal distance ranged from the 3rd to 100th percentiles, with the mean at the 59th percentile and SEM of 10. Outer canthal distance ranged from the 6th to the 81st percentile, with mean at the 43 percentile and SEM of 7. Canthal index ranged from −2 to +2 SD from the normal mean.

Growth

Ten of 12 subjects were born at term and 2 were born at 36 and 34 weeks, respectively. In the majority of individuals, birth weight, length, and occipital-frontal circumference were appropriate for gestational age. Individuals grew poorly after mid-childhood, with weight affected more than height. Acquired microcephaly was documented in the four oldest subjects (Supplementary Figure S1 online). The total foot length was less than the third percentile for all 12 individuals.

Nijmegen scores

The 11 individuals younger than age 18 years were evaluated using the Nijmegen Pediatric CDG Severity scale.14 Total Nijmegen scores ranged from 9 (mild) to 52 (severe), with a mean of 28 ± 4 (SEM); the median was 32 ( Table 1 , Supplementary Table S1 online). Based on definitions by Achouitar et al.,14 three individuals had scores in the mild range, two in the moderate range, and six in the severe range. All five individuals carrying the common mutation c.1201A>T were either moderately or severely impaired; those carrying at least one copy had a higher mean score (36) than those without this mutation (20.5) (P = 0.0184). The sibling pair (individuals 7 and 8) with a private cryptic splice-site mutation (c.930C>T) and a private nonsense mutation (c.622C>T) both exhibited relatively mild impairment in all domains. All other mutations were private, precluding additional genotype–phenotype correlations. There was no significant difference in disease severity of males compared with females (data not shown).

Development

All 12 subjects had at least some developmental delay or intellectual disability, with a broad range of severity ( Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1 online). IQ was below average (n = 2) or in the range of intellectual disability (n = 9) for the entire group; seven individuals had profound intellectual disability. The two individuals with IQ below average were verbally fluent; the remainder were nonverbal (n = 7) or used only single words (n = 1) or phrase speech (n = 1).

On the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (second edition),13 composite scores ranged from 24 to 98, with a mean of 51 (SEM = 7) ( Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1 online). There was a consistent profile characterized by relatively strong socialization scores, followed by communication and daily living skills (Supplementary Figure S2 online). Motor deficits were also reflected in impaired daily living skills scores. Vineland scores were higher than cognitive scores for all subjects. We found no cross-sectional relationship between age and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Composite.

Neurologic phenotype

Seven of 12 subjects had clinical seizures, and 1 had subclinical seizures recognized on previous EEG. Details regarding age of onset, seizure type and frequency, medications, and EEG findings are noted in Supplementary Table S2 online. On overnight EEG, only one individual (patient 6) had active seizures recorded, but seven had multifocal epileptiform activity. There were no age or genotype differences between individuals with seizures and those without. In fact, in each sibling pair, one had seizures and the other did not.

All 12 individuals exhibited hyperkinetic movement disorders that included choreiform, athetoid, dystonic, myoclonic, action tremor, and dysmetric movements, and were more severe in younger individuals (Supplementary Movie S1 online).

Brain MRI and MRS

Eleven individuals underwent MRI and MRS of the brain. Clinical assessment of the images was not striking ( Figure 3 ). Delayed myelination was present in three of the four youngest individuals, but all the older individuals had complete myelination. Six of nine individuals had qualitatively evident cerebral atrophy that ranged from slight to moderate. Four individuals (patients 1, 2, 6, and 10) also had slight cerebellar atrophy. The atrophy tended to be greater in older individuals (P = 0.17, Supplementary Figure S3 online); in one teenager (patient 11), follow-up imaging showed that atrophy was measurably worse after a 20-month interval (net loss of 34 cm3 relative to expected). Increased atrophy correlated with worsening of all functional measurements (Supplementary Figure S3 online), including IQ or developmental quotient (P < 0.03), Vineland assessments (P < 0.03), and Nijmegen scores (P = 0.01). Brain volume also directly correlated with CSF levels of 5-HIAA (P = 0.03), tetrahydrobiopterin (P = 0.02), and 5- homovanillic acid (HVA) (P = 0.06) (Supplementary Figure S3 online).

Brain MRI findings. White matter lesions were seen in 2 of 11 individuals. Panel a shows multiple lesions in the periventricular white matter, some of which were confluent. Panel b shows a single lesion in the periventricular white matter. Both a and b illustrate cerebral atrophy and were performed using T2 weighting. Sulci are slightly prominent in both a and b, and prominent ventricles are visible in a. Panel c illustrates the high position of the cerebellar tonsils, large foramen of Magendie, and cisterna magna.

Compared with the reference population, N-acetylaspartylglutamate plus N-acetylaspartate (NAA) was lower than normal in the left centrum semiovale (LCSO) (P = 0.004), the midline parietal gray matter (PGM) (P = 0.02), and superior cerebellar vermis (SVERM) (P < 0.0001). There was a deficit of glutamine plus glutamate plus gamma-aminobutyric acid (Glx) in the PGM (P = 0.03), LCSO (P = 0.01), and pons (P = 0.0002). Choline was higher than expected for age only in the LCSO (P = 0.0097), and myo-inositol was higher than expected for age in the pons (P = 0.002). Multiple correlations between these MRS-measured metabolites and age, functional assessments, brain volume, and neurotransmitters in the CSF were found (Supplementary Figure S3 online). The general trend showed that these differences became more pronounced with increasing age, worsening function, and lower brain volume (Supplementary Figure S4 online). MRS metabolite measurements did not correlate with total CSF protein, CSF albumin, or CSF/serum albumin ratio. There was a weak correlation (P = 0.09) between atrophy and total CSF protein, but not CSF albumin or CSF/serum albumin ratio.

CSF laboratory results

Nine subjects underwent lumbar puncture. CSF total protein and albumin concentrations, as well as the CSF/serum albumin ratios, were low in nearly all individuals (Supplementary Table S3 online). There was no correlation between age and CSF protein or albumin levels. In the two oldest subjects, CSF 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid (5-HIAA) and HVA were decreased, suggesting neuronal loss. Neopterin levels were normal but decreased with age, and CSF tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) levels were below the lower limit of normal in all but one subject tested; however, there was no correlation with age. CSF 5-HIAA, HVA, and BH4 levels strongly and directly correlated with brain atrophy. CSF lactate and amino acid levels were essentially normal (Supplementary Table S3 online). CSF leukocyte counts (0–4; normal 0–5), glucose concentrations (54–72 mg/dl; normal 40–70), 3-O-methyldopa concentrations (12–28 nmol/l; normal <150), and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate concentrations (45–85 nmol/l; normal 40–150) were unremarkable (data not shown).

Nerve conduction studies, electromyogram, and QSWEAT testing

Nerve conduction studies were performed in 11 individuals (Supplementary Table S4 online). The predominant finding was an axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy (n = 8) with additional demyelinative features (n = 6). Results of neurophysiological testing demonstrated a length-dependent, progressive loss of sensory and motor axons and sympathetic nerve function, apparently static abnormalities in myelination of peripheral nerves, and possible motor neuron degeneration. A single individual (patient 6) had a repeat study at 1 year that showed progression of the neuropathy. On needle electromyogram, neurogenic findings were noted in nine subjects with varying degrees of acute and chronic changes consistent with the nerve conduction studies results.

QSWEATs, performed in 11 individuals, were abnormal in the same 8 individuals who had axonal sensorimotor neuropathies. The distal lower extremity QSWEAT was more frequently absent (7/11) compared with the forearm (1/11), consistent with a length-dependent neuropathy. There was a trend to greater severity of neuropathy in older individuals, with an inverse correlation between tibial motor amplitude and age (P = 0.002, r2 = 0.799); the amplitude decreased by −0.3 mV per year (normal, >+2.5 mV per year).

Ophthalmology

Awake and sedated ophthalmic examinations were performed for 11 study participants (Supplementary Table S5 online). Lagophthalmous, ptosis, exotropia and/or esotropia, corneal neovascularization, pannus formation or scarring, optic nerve pallor or atrophy, retinal pigmentary changes including pigment granularity and pigmentary retinopathy or pigmentary changes, blonde or poorly pigmented retinal periphery, and refractive errors were observed ( Figure 4 ). All individuals had evidence of hypo- or complete alacrima on Schirmer II testing (Supplementary Table S5 online). Tear production did not correlate with age. One participant underwent sedated electroretinography and was diagnosed with cone dystrophy; the photopic responses were reduced to ~50% of the lower limit of normal for age.

Audiology

Audiologic assessments, including otoacoustic emissions and/or cochlear microphonics to evaluate for the functional integrity of the inner ear, and auditory brainstem response (ABRs) were conducted for 11 subjects. Behavioral hearing thresholds could be established reliably for only three subjects, and all had normal hearing sensitivity. Tympanometry was unremarkable. Most remarkable was the dyssynchronous and/or absent transmission through the auditory brainstem and/or eighth nerve in most individuals. The severity of transmission abnormality through the auditory brainstem increased with increasing age, and the eighth nerve was bilaterally involved in the four oldest individuals (Supplementary Table S6 online).

Clinical feeding and swallowing assessments

Clinical feeding and modified barium swallow assessments were performed in 11 subjects. Oral motor deficits, including persistent nutritive suckle swallow and poor oral bolus formation, were present in 10 of 11 subjects. Premature spillage and pharyngeal swallow response delays remained the primary deficits of all subjects. No aspiration or laryngeal penetration for any textures was observed in the swallow studies. Developmental delays in mastication were evident and characterized by munching patterns without matured rotary chewing of solid textures. Generalized weakness of the lips and tongue was observed in all individuals during cranial nerve assessments. Dystonic movements of the tongue and persistent oral reflexes of suckling and suck/swallows were seen in the majority of individuals.

Cardiorespiratory status

Echocardiogram results were unremarkable (n = 12). Electrocardiogram results showed heart rates in the low 100s in all subjects (n = 12), with two individuals having QTcB >440 ms but a normal QTcF. Sleep studies (n = 9) identified evidence of obstructive sleep apnea (n = 2), central sleep apnea (n = 1), and combined obstructive and central sleep apnea (n = 2). Five individuals had frequent periodic limb movements. There were no associations between age and either sleep apnea or frequent periodic limb movements.

Gastrointestinal and nutritional findings

Gastric pH was assessed after H2 blockers and osmotic pump inhibitors had been discontinued for 5 days. Gastric pH was appropriately acidic in all individuals tested except one, whose pH was 7.25. Ten of 12 individuals had some degree of constipation. Abdominal ultrasound results were normal for 6 of 12 individuals. Abnormalities in abdominal ultrasound included splenomegaly, steatosis, coarse or inhomogeneous liver texture, or hepatomegaly. No hydronephrosis, polycystic kidneys, horseshoe kidneys, kidney calculi, nephrocalcinosis, or perinephric fluid was seen. Three of 12 had Fibroscan scores >7 kPa, which is the upper limit of normal, indicating possible liver fibrosis. Resting energy expenditure was close to 100% of expected in 3 individuals, but ranged from 51 to 82% of predicted in the other 9 (data not shown).

Laboratory values reflecting gastrointestinal and hepatic function were essentially normal at the time of the NIH evaluation (Supplementary Table S7 online). However, chart review revealed elevations in aspartate aminotransferase and/or alanine transaminase in all eight subjects who had these measured during their first 2 years of life. One individual had undergone liver transplantation for presumed hepatocellular carcinoma (further details in Supplementary Materials and Methods online). These transaminase levels normalized at approximately age 4 (Supplementary Figure S5 online). Circulating proteins were normal or borderline low in all individuals (Supplementary Table S7 online). Total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides were also low (Supplementary Table S7 online). In the two subjects with the lowest cholesterol levels, high-density lipoprotein, LDL, and very-low-density lipoprotein particle numbers and sizes were normal (data not shown).

Hematologic, endocrine, immunologic, and biochemical phenotype

Hematologic profiles showed unremarkable complete blood counts (Supplementary Table S8 online), with the exception of one subject with lymphoblasts who was subsequently diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia (Supplementary Results online). Coagulation studies showed normal prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and international normalized ratio, but low protein C activity (n = 6), factor II activity (n = 1), factor IX (n = 2), factor XI (n = 2), and fibrinogen (n = 5) (Supplementary Table S8 online). On average, all factors except for antithrombin III were lower in individuals with the c.1201A>T mutation; for factor II, factor IX, and factor XI, the differences were significant at P < 0.05 using the two-sample t-test.

Detailed laboratory analyses of endocrine (Supplementary Table S9 online) and immune (Supplementary Table S10 online) functions were performed. The most striking finding was that 7 of 11 individuals tested exhibited out-of-range elevations in antibody titers toward rubella and/or rubeola after receiving the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccination. Biochemical markers known to be abnormal in mitochondropathies and hypoglycosylation disorders showed inconsistent results (Supplementary Tables S11 and S12 online).

Musculoskeletal findings

Bone age was delayed in 8 of the 11 subjects tested without any consistent abnormalities of the endocrine system; the somatotropic axis and thyroid function were normal in all studied individuals. Femoral bone density was low in all nine individuals who underwent dual X-ray absorptiometry scanning (mean and SEM z-scores for 8 patients younger than 21 years adjacent to the growth plate = −3 and 0.4; metaphysis-diaphysis = −2.2 and 0.6; and diaphysis = −1.8 and 0.5). All subjects except the older ones had joint hypermobility; older subjects had contractures in small and large joints. Complete skeletal surveys were performed for 11 individuals; abnormalities included coxa valga (n = 11), scoliosis (n = 6), growth arrest lines or metaphyseal banding without palmidronate treatment (n = 4), dislocations or subluxations involving the hips and shoulder joints (n = 3), and sclerosis of the phalanges or tarsal bones (n = 2). Findings noted only once included flexion deformity of the fingers, hallux valgus, sclerotic lesion of the distal femur, thinning of the fibulas, prominent apophyseal bone formation in the ileac crests and ischia, ulnar bowing, expansion of the cortexes in the proximal and middle phalanges in digits 2–4, widened phalanges, and shortened and widened metatarsals.

Discussion

Summary of novel findings

Our prospective investigations into NGLY1-CDDG revealed several new discoveries associated with this disorder. These included low CSF total protein and albumin, optic atrophy and retinal pigmentary changes/cone dystrophy, poor weight gain starting in mid-childhood, lower than predicted resting energy expenditure, central and obstructive sleep apnea, delayed bone age, joint hypermobility, progressive brain atrophy, abnormalities in brain MRS-measured metabolites, various abnormalities on skeletal survey, high antibody titers after rubella and rubeola vaccination, and low levels of several pro-coagulation and anti-coagulation factors. Echocardiogram results, electrocardiogram results, and CSF lactate levels were normal.

We also confirmed and further detailed the global developmental delay, movement disorder, frequent seizure disorder, hypotonia, hypolacrima or alacrima, corneal disease, ptosis, lagophthalmous, strabismus, peripheral neuropathy and occasional diminished reflexes, hypohidrosis, auditory brainstem response abnormalities, abnormal brain imaging, scoliosis, acquired microcephaly, small hands and feet, dysmorphic features, constipation, elevated liver enzymes present only early in childhood, osteopenia, and hypocholesterolemia associated with NGLY1-CDDG. Compared with previously reported biopsy findings, our transient elastography results showed minimal, if any, fibrosis. In addition, we could not confirm abnormal storage material in the three liver biopsy specimens we analyzed, nor did we observe ocular apraxia in our individuals despite performing detailed ophthalmologic evaluations that involved some subjects previously reported to have ocular apraxia.11

Based on our findings, we recommend considering NGLY1-CDDG in the differential diagnosis of any patient with the tetrad of developmental delay/intellectual disability, hyperkinetic movement disorder, hypolacrima, and a history of elevated transaminases during early childhood.

Therapeutic implications

Several specific phenotypic findings have therapeutic implications. The auditory neural pathway dysfunction without peripheral hearing loss resembles that observed in auditory neuropathy. Persons with auditory neuropathy experience difficulty hearing in the presence of background noise and benefit from quiet listening environments.21 If hypohidrosis is detected, then preventive measures (e.g., hydration and ventilation.) against situations that cause dangerous core body hyperthermia can be taken. It is important to aggressively manage hypolacrima with artificial tears and bland ointment to prevent secondary complications that can impact vision. The finding of disordered mastication for solids but a functional ability to swallow suggests the need for oral motor and swallowing therapies for all subjects to facilitate better control and chewing maturation.

Motor skills scores were low and resembled the daily living skills scores, reflecting the significant motor involvement required for daily tasks. This suggests that if motor deficits and the hyperkinetic movement disorder of NGLY1-CDDG could be treated effectively, then quality of life could be significantly improved. Contributors to the movement disorder that could be targeted include myoclonic seizures, neurotransmitter deficiency, and/or peripheral neuropathy manifesting as sensory ataxia.

Hypotheses generated for pathophysiology of clinical findings

Our detailed assessment of the phenotypic features has also led to several hypotheses regarding underlying pathophysiology. The strong correlation between brain atrophy on MRI and functional assessments suggests that loss of neurons contributes to the functional impairment. The atrophy also correlated with CSF metabolites (BH4, 5-HIAA, HVA), which are known to be lower when there is damage to neurotransmitter-producing neurons.22,23,24 This suggests that these biochemical abnormalities may be secondary to brain atrophy.

Results from MRS showed that as functional impairment worsened and age increased, NAA decreased and choline, myo-inositol, and creatine increased. Additionally, creatine and myoinositol were inversely correlated and NAA was directly correlated with neurotransmitter levels (5-HIAA, 5-HVA, 3-OMD, and neopterin, Supplementary Figure S3 online). NAA may be found exclusively in neurons and declines as neurons become unhealthy or die.25,26 Elevations in choline could be consistent with a relative abundance of glial cells secondary to neuronal loss.26 Myo-inositol is a glia-specific marker that is elevated by gliosis or inflammation27,28; in our cohort we do not have any evidence of inflammation. Creatine levels are relatively higher in glial cells compared with neurons.29 Taken together, the MRS findings suggest that there is a relative abundance of glial cells compared to neurons in the brain of NGLY1-CDDG individuals, possibly due to loss of neurons, and that the degree of this imbalance contributes significantly to the severity of the phenotype.

The impaired sweat response, largely affecting distal responses, is consistent with a small fiber neuropathy rather than a central etiology or generalized cholinergic dysfunction. Albumin CSF/serum quotient, or QAlb, is a marker of blood–CSF barrier dysfunction, and its value is inversely correlated to the CSF turnover rate.30 There was no significant change in the QAlb ratio (data not shown), arguing against increased turnover as a possible etiology. Regardless of the mechanism, we propose that decreased CSF protein and albumin concentrations represent a novel diagnostic marker for this disorder.

Individuals with NGLY1-CDDG and those with N-linked glycosylation disorders share the phenotypic features of low cholesterol, hepatopathy, peripheral neuropathy, retinal and optic nerve abnormalities, seizures, developmental delay with socialization as a relative strength, and delayed bone age.18 NGLY1-CDDG also overlaps with O-linked glycosylation disorders with respect to hypolacrima.19 There may be a pathogenic relationship; N-glycanase 1 catalyzes the cleavage of the amide bond between the proximal N-acetylglucosamine residue of glycans and the asparagine residue of the protein,9 so NGLY1-CDDG could impair glycan recycling and lead to hypoglycosylation. The individuals with NGLY1-CDDG exhibited subtle abnormalities in transferrin and ApoC-III glycosylation.20

Another hypothesis for the etiology of the NGLY1-CDDG phenotype is based on the fact that misfolded glycoproteins are processed through the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway (ERAD) and then retrotranslocated into the cytoplasm. There, N-glycanase is the first step in further degradation of these molecules, making ERAD dysfunction a possible pathophysiologic contributor, especially given evidence of ER stress in mouse embryonic fibroblasts.31 However, preliminary experiments found no impairment or enhancement of standard ERAD marker expression under normal conditions in NGLY1-CDDG patient fibroblasts (H. H. Freeze, personal communication, April 2016).

Age progression of disease and implications for future therapeutic trials

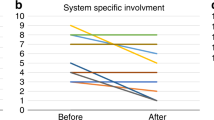

Our study, which documents cross-sectional findings and covers a large range of ages, indicates that NGLY1-CDDG is a progressive disorder. The Nijmegen severity scores and Vineland scores indicated worsening function with age. Also progressive were the peripheral neuropathy, auditory neural dysfunction, scoliosis, inability to maintain weight, brain atrophy on MRI, abnormalities in brain metabolites measured on MRS, and CSF neurotransmitter levels.

However, other aspects of N-glycanase deficiency appear static or even regressive. Hypolacrima occurred at all ages, and the hepatopathy and hyperkinetic movement disorder appeared to improve with age. These observations provide a guide to determine reliable outcome measures for efficacy in future therapeutic trials. Effective outcome measures would be derived from findings that are progressive, such as brain volume, choline levels on MRS, nerve conduction velocities and amplitudes, and auditory brainstem-evoked responses.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Ferguson MAJ, Kinoshita T, Hart GW. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors. In: Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, et al., eds. Essentials of Glycobiology. 2nd edn.Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 2009.

Hennet T. Diseases of glycosylation beyond classical congenital disorders of glycosylation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1820:1306–1317.

Simpson MA, Cross H, Proukakis C, et al. Infantile-onset symptomatic epilepsy syndrome caused by a homozygous loss-of-function mutation of GM3 synthase. Nat Genet 2004;36:1225–1229.

Jaeken J, Vanderschueren-Lodeweyckx M, Casaer P, et al. Familial psychomotor retardation with markedly fluctuating serum prolactin, FSH and GH levels, partial TBG-deficiency, increased serum arylsulfatase-A and increased CSF protein: a new syndrome? (abst 90). Pediatr Res 1980;14:179.

Jaeken J, van Eijk HG, van der Heul C, Corbeel L, Eeckels R, Eggermont E. Sialic acid-deficient serum and cerebrospinal fluid transferrin in a newly recognized genetic syndrome. Clin Chim Acta 1984;144:245–247.

Freeze HH, Chong JX, Bamshad MJ, Ng BG. Solving glycosylation disorders: fundamental approaches reveal complicated pathways. Am J Hum Genet 2014;94:161–175.

Matthijs G, Rymen D, Millón MB, Souche E, Race V. Approaches to homozygosity mapping and exome sequencing for the identification of novel types of CDG. Glycoconj J 2013;30:67–76.

Need AC, Shashi V, Hitomi Y, et al. Clinical application of exome sequencing in undiagnosed genetic conditions. J Med Genet 2012;49:353–361.

Takahashi N. Demonstration of a new amidase acting on glycopeptides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1977;76:1194–1201.

Might M, Wilsey M. The shifting model in clinical diagnostics: how next-generation sequencing and families are altering the way rare diseases are discovered, studied, and treated. Genet Med 2014;16:736–737.

Enns GM, Shashi V, Bainbridge M, et al.; FORGE Canada Consortium. Mutations in NGLY1 cause an inherited disorder of the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway. Genet Med 2014;16:751–758.

Bonder A, Afdhal N. Utilization of FibroScan in clinical practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2014;16:372.

Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Balla DA. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition. In: Service AG, ed. 2nd edn. AGS Publishing: Circle Pines, MN, 2005.

Achouitar S, Mohamed M, Gardeitchik T, et al. Nijmegen paediatric CDG rating scale: a novel tool to assess disease progression. J Inherit Metab Dis 2011;34:923–927.

Caglayan AO, Comu S, Baranoski JF, et al. NGLY1 mutation causes neuromotor impairment, intellectual disability, and neuropathy. Eur J Med Genet 2015;58:39–43.

Heeley J, Shinawi M. Multi-systemic involvement in NGLY1-related disorder caused by two novel mutations. Am J Med Genet A 2015;167A:816–820.

Suzuki T. The cytoplasmic peptide:N-glycanase (Ngly1)-basic science encounters a human genetic disorder. J Biochem 2015;157:23–34.

Sparks SE, Krasnewich DM. Congenital Disorders of N-linked Glycosylation Pathway Overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al, eds. GeneReviews(R). University of Washington: Seattle, WA, 1993.

Koehler K, Malik M, Mahmood S, et al. Mutations in GMPPA cause a glycosylation disorder characterized by intellectual disability and autonomic dysfunction. Am J Hum Genet 2013;93:727–734.

Barone R, Carchon H, Jansen E, et al. Lysosomal enzyme activities in serum and leukocytes from patients with carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type IA (phosphomannomutase deficiency). J Inherit Metab Dis 1998;21:167–172.

Starr A, Rance G. Auditory neuropathy. Handb Clin Neurol 2015;129:495–508.

Nakamura S, Koshimura K, Kato T, et al. Neurotransmitters in dementia. Clin Ther 1984;7 Spec No:18–34.

Marín-Valencia I, Serrano M, Ormazabal A, et al. Biochemical diagnosis of dopaminergic disturbances in paediatric patients: analysis of cerebrospinal fluid homovanillic acid and other biogenic amines. Clin Biochem 2008;41:1306–1315.

García-Cazorla A, Serrano M, Pérez-Dueñas B, et al. Secondary abnormalities of neurotransmitters in infants with neurological disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol 2007;49:740–744.

Simmons ML, Frondoza CG, Coyle JT. Immunocytochemical localization of N-acetyl-aspartate with monoclonal antibodies. Neuroscience 1991;45:37–45.

Miller BL. A review of chemical issues in 1H NMR spectroscopy: N-acetyl-L-aspartate, creatine and choline. NMR Biomed 1991;4:47–52.

Brand A, Richter-Landsberg C, Leibfritz D. Multinuclear NMR studies on the energy metabolism of glial and neuronal cells. Dev Neurosci 1993;15:289–298.

Bitsch A, Bruhn H, Vougioukas V, et al. Inflammatory CNS demyelination: histopathologic correlation with in vivo quantitative proton MR spectroscopy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999;20:1619–1627.

Bhakoo KK, Williams IT, Williams SR, Gadian DG, Noble MD. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of primary cells derived from nervous tissue. J Neurochem 1996;66:1254–1263.

Deisenhammer F, Bartos A, Egg R, et al.; EFNS Task Force. Guidelines on routine cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Report from an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol 2006;13:913–922.

Huang C, Harada Y, Hosomi A, et al. Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase forms N-GlcNAc protein aggregates during ER-associated degradation in Ngly1-defective cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015;112:1398–1403.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Common Fund, Office of the Director, and the Intramural Research Program of the NHGRI and NIDCD, NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. We sincerely thank all the individuals and their families for participating in this study, and the advocacy groups NGLY1.org and the Grace Science Foundation, which provided encouragement and emotional support. We thank Hudson Freeze, Kathy Grange, Mena Scavina, Michael J. Gambello, J. Lawrence Merritt II, Marni Falk, and Marwan Shinawi for referring and caring for the affected individuals. We thank Jaak Jaeken for his input regarding the “official naming” of this disorder. Additionally, we are immensely grateful to our collaborators, colleagues, and technical/laboratory assistants for providing continuous discussion, support, and direction for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Methods

(ZIP 7516 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lam, C., Ferreira, C., Krasnewich, D. et al. Prospective phenotyping of NGLY1-CDDG, the first congenital disorder of deglycosylation. Genet Med 19, 160–168 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.75

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.75

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Gut barrier defects, intestinal immune hyperactivation and enhanced lipid catabolism drive lethality in NGLY1-deficient Drosophila

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Shedding light on NGLY1 deficiency: a call for awareness and support

Journal of Rare Diseases (2023)

-

NGLY1 deficiency: estimated incidence, clinical features, and genotypic spectrum from the NGLY1 Registry

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2022)

-

Deficiency of N-glycanase 1 perturbs neurogenesis and cerebral development modeled by human organoids

Cell Death & Disease (2022)

-

Reversibility of motor dysfunction in the rat model of NGLY1 deficiency

Molecular Brain (2021)