Abstract

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), an autosomal dominant disorder, is a multisystem disease with manifestations in the central nervous system, kidneys, skin and/or heart. Most TSC patients carry a pathogenic mutation in either TSC1 or TSC2. All types of mutations, including large rearrangements, nonsense, missense and frameshift mutations, have been identified in both genes, although large rearrangements in TSC1 are scarce. In this study, we describe the identification and characterisation of eight large rearrangements in TSC1 using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) in a cohort of 327 patients, in whom no pathogenic mutation was identified after sequence analysis of both TSC1 and TSC2 and MLPA analysis of TSC2. In four families, deletions only affecting the non-coding exon 1 were identified. In one case, loss of TSC1 mRNA expression from the affected allele indicated that exon 1 deletions are inactivating mutations. Although the number of TSC patients with large rearrangements of TSC1 is small, these patients tend to have a somewhat milder phenotype compared with the group of patients with small TSC1 mutations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC, MIM no. 191 100) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterised by seizures, mental retardation and hamartomas in multiple organ systems, including brain, skin, heart, lungs and kidneys.1 Mutations in either TSC1 or TSC2 are the underlying cause of the clinical symptoms in TSC patients. In about 75–85% of the patients meeting the definite clinical criteria, a pathogenic TSC1 or TSC2 mutation is identified.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 The genes are categorised as tumour suppressor genes, as loss of heterozygosity has been shown in TSC-associated lesions.8

TSC1 consists of 23 exons, of which exon 1 and 2 are non-coding. A core promoter has been defined by functional analysis.9 This region of 587 bp of size is situated 510 bp upstream of exon 1 and runs into exon 1. No TATA or CAAT boxes are present in this promoter region. Several transcription factor-binding sites are present including SP1, E2F and GATA sites. For the detection of small (point) mutations in TSC1 and TSC2, several screening technologies have been undertaken: denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE), single strand conformation polymorphism, protein truncation test, denaturing high-pressure liquid chromatography and direct sequencing.3, 5, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Larger rearrangements have been detected by fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH), southern blotting, long-range (LR) PCR and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis.15, 16, 17, 18 Mutations in TSC2 are more common than in TSC1, particularly in sporadic cases. Interestingly, although large rearrangements account for approximately 10% of all TSC2 mutations identified to date, they appear to be much less frequent in TSC1. To our knowledge, only eight different TSC1 deletions have been described so far.18, 19, 20

MLPA analysis of TSC1 was undertaken in patients suspected of TSC, in whom no pathogenic mutation had been identified in either TSC1 or TSC2. In four cases, a deletion of the non-coding exon 1 was identified and in a further four cases multi-exon deletions were detected. The deletions were characterised and it was demonstrated that deletion of exon 1 prevents TSC1 expression.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

Samples of patients with either a putative or definite clinical diagnosis of TSC were received for mutation analysis. Details on clinical symptoms were obtained from the referring physician using a standardised clinical evaluation form.3

Mutation analysis

Extraction of DNA from peripheral blood cells was performed according to the standard techniques. Mutation analysis of TSC1 and TSC2 was performed by DGGE3 or by direct sequence analysis of all coding exons and exon/intron boundaries (primers available on request). For the detection of large rearrangements in TSC2, southern blotting, FISH and/or MLPA were performed. After the introduction of MLPA for TSC1, all patients without an identified pathogenic mutation were tested using the SALSA MLPA kit P124 (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). MLPA was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions; products were run on an automated sequencer (ABI 3730XL, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and data were analysed using Genemarker version 1.5 (Softgenetics, State College, PA, USA). If possible, all pathogenic mutations were confirmed on an independent DNA sample.

Quantitative (Q)-PCR, LR-PCR and sequence analysis of breakpoints

All apparent deletions detected by MLPA were confirmed by further delineation of the breakpoint regions using Q-PCR, followed by LR-PCR and sequence analysis.

Real-time Q-PCR was performed using Fam-labelled Taqman assays.21 Primers were designed with Primer Express 2.0.0 (Applied Biosystems) in the vicinity of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) mapping to the TSC1 locus (Table 1). Primer specificity was checked by performing BLAST analysis. Taqman probes were synthesised with a melting temperature (Tm) 8–10 °C higher than the primers by incorporating locked nucleic acid (LNA) monomers in the probe. Tm values for the LNA probes were calculated using the Exiqon website (http://lna-tm.com/). The LNA-based Taqman assays were manufactured by Eurogentec (Maastricht, The Netherlands).

Gene dosage alterations were detected on an ABI7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) by performing a relative quantification run. Real-time PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 25 μl, containing 20 ng DNA, 1 × qPCR mastermix Plus-low ROX (Eurogentec: RT-QP2x-03-WOULR), 1 × RNAse P (endogenous control) (Applied Biosystems), 30 μ M forward and reverse primers and 10 μ M probe. PCR conditions were as follows: an initial 2 min incubation at 50 °C, followed by 95 °C for 10 min and then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. All samples were analysed in triplicate and compared with a normal control sample.22

LR-PCR was performed with the Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). LR-PCR products were sequenced using an automated sequencer (ABI 3730XL). Nomenclature of the deletions is according to the recommendations of the Human Genome Variation Society, using reference sequence NM_000368 (17 December 2004; build 36, NCBI).

RNA analysis

Fibroblasts were cultured according to the standard procedures. To increase the probability of recovering (truncating) mutant TSC1 RNA, nonsense-mediated decay of RNA was prevented by adding cycloheximide to the cells 4.5 h before harvesting. RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen Inc, Valencia, CA, USA). Reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR (oligo-dT primed) was performed using the Omniscript ReverseTranscription kit (Qiagen). The primers used for RNA analysis were as follows:

Exon 20, forward: 5′-TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTACAGGCAGCTGTTGGTTCTT-3′

Exon 23, reverse: 5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCGCCAGATGCCTCTTCATTGT-3′

Exon 20/21, forward: 5′-TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGCACTCAGATACCACAAAGGAA-3′

Exon 23, reverse: 5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCTCTGAGCACCCGTCATTACA-3′

A first round PCR was performed, followed by a nested PCR using 1 μl of the first round PCR product. The PCR conditions were: 10 s at 94 °C, followed by 10 cycles of 30 s 94 °C, 30 s 68 °C, 1 min 72 °C with a decrease of 1 °C in the annealing temperature per cycle, an additional 25 cycles with an annealing temperature of 58 °C and finally 5 min at 72 °C and 5 min at 20 °C. PCR products were directly sequenced using an automated sequencer (ABI 3730XL). Data were analysed using the SeqScape software (version 2.6; Applied Biosystems).

Results

Mutation analysis

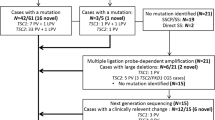

Mutation analysis was performed in a diagnostic cohort of 986 TSC cases. This cohort includes the group (n=362) previously described.3 Of those 362 patients, 276 (76%) had a definitive clinical diagnosis of TSC. In the total group of 986 patients, it was not possible to give a percentage of patients meeting the clinical diagnosis TSC, as no clinical information was available of the new patients. In 172 cases (17.4%), a pathogenic mutation in TSC1 was identified, whereas TSC2 mutations were present in 487 cases (49.3%; data not shown). In 327 cases (33.2%), no pathogenic mutation was identified in TSC1 (by direct sequence or DGGE analysis of all coding exons) or TSC2 (by direct sequence, DGGE, southern, FISH and MLPA analysis). MLPA analysis of TSC1 in these 327 patients showed abnormal patterns in 8 unrelated patients: in 4 cases (patient numbers 30 628, 21 722, 21 899 and 1264; Figures 1b–e), a deletion of the non-coding exon 1 was detected, 1 patient (31 457; Figure 1f) had a deletion of exons 2–23, 2 patients (29 445 and 28 121; Figure 1g–h) had a deletion of exons 9–23 and 1 patient (14 249; Figure 1i) was identified with a total gene deletion (Figure 1).

MLPA results. Shown are the graphs after analysis with the Genemarker software. A value of 0.7 or lower is an indication of a deletion of that probe region. (a) A sample with a normal pattern (negative control), (b) patient 30 628, (c) patient 21 722, (d) patient 21 899, (e) patient 1264, (f) patient 31 457, (g) patient 29 445, (h) patient 28 121 and (i) patient 14 249.

Characterisation of the breakpoints

Direct sequence analysis of exon 1 of the four patients with an aberrant MLPA pattern for exon 1 was undertaken to exclude the presence of a SNP interfering with the MLPA probes. No abnormality was identified, indicating that the MLPA results were very likely because of the deletions of this region. To delineate all deleted regions, Q-PCR analyses were performed at several points upstream and downstream of the exon(s) involved in the deletions, followed by LR-PCR using the Q-PCR primers mapping just outside the deleted regions. The breakpoints were identified by sequencing the aberrant LR-PCR products. All four exon 1 deletions had different breakpoints, all resulting in a complete loss of exon 1 (Figure 2). Three of the four deletions did not show a deletion only. In patients 30 628 and 21 722 also an inversion of 56 and 156 nucleotides, respectively, was present. In patient 21 899, an even more complex rearrangement of two deleted regions and an insertion of seven nucleotides was identified. The exon 1 deletion observed in patient 1264 and the multi-exon deletions in the other families (31 457, 29 445, 28 121 and 14 249) did not contain inserted or inverted nucleotides. Only the deletion in patient 28 121 was entirely intragenic. The 5′ breakpoint was located in intron 8 and the 3′ breakpoint in the 3′ UTR of exon 23. The three other deletions started either in the TSC1 upstream region, in intron 1 or in intron 8 and extended into the TSC1 downstream region. None of the eight breakpoint junctions showed a sequence that could be an obvious trigger for the rearrangements (Table 2). The TSC1 promoter region is located between nucleotide positions 16 271 and 15 683 upstream of the ATG codon in exon 3,9 indicating that three out of the four patients with a complete exon 1 deletion also lack the promoter region. Patient 1264 had a partial deletion of the promoter region. The 155 nucleotides of the 5′ end of the promoter region were still present in this patient.

Overview of the TSC1 deletions identified during this study and described previously. The upper part of the figure represents the genomic region extending from exon 1 to exon 23 of TSC1 (not drawn on scale). The closed box represents the promoter region and the open boxes represent TSC1 exons. If the breakpoints of the deletion have been determined, this is given by the HGVS nomenclature (reference sequence NM_000368 (17 December 2004; build 36, NCBI)); ND: breakpoint is not determined; 2.3 kb: in the article of Kozlowski et al18 only the length of the deletion is given. On the right side of each deletion the identification number of the patient is given, followed by the indication S (sporadic), F (familial), ND (not determined) and, if previously published, the references: *Kozlowski et al,18 **Longa et al,19 ***Nellist et al.20

RNA analysis

Because exon 1 is a non-coding exon, it was not clear whether deletion of this exon would be pathogenic, nor whether it would have an effect on the expression of TSC1. Only one patient (21 899) was heterozygous for a coding SNP in TSC1 (c.2829C>T in TSC1 exon 22 (rs4962081; Figure 3a), allowing to assess which alleles of TSC1 were expressed in this patient. To demonstrate equal expression of both alleles of TSC1 in cultured fibroblast cells, control RNA from another individual heterozygous for this SNP, was analysed by RT-PCR. Expression of both alleles could be demonstrated in the control RNA, as the RNA showed a heterozygous pattern for the SNP (Figure 3b). In contrast, RNA from patient 21 899 showed only the T nucleotide of SNP rs4962081, indicating monoallelic expression of TSC1 (Figure 3c). We concluded that the deletion of exon 1 in this patient prevented TSC1 expression and deletions affecting this non-coding exon are therefore pathogenic mutations.

RNA analysis of the coding SNP rs4962081 in exon 22 of TSC1. (a) Genomic DNA of patient 21 899. The intron–exon boundary is given by a vertical line. The heterozygous pattern of SNP rs4962081 is recognised by ‘Y’ (C/T combination). (b) RNA of a control individual heterozygous for SNP rs4962081. The boundary between exons 21 and 22 is given by a vertical line. The heterozygous pattern is called by ‘Y’ (C/T combination). (c) RNA of patient 21 899. The boundary between exon 21 to exon 22 is given by a vertical line. Patient 21 899, who is heterozygous for SNP rs4962081 in genomic DNA (see a above), shows expression of only the ‘T’ allele, indicating monoallelic expression of TSC1.

Deletion-specific PCR analysis

Because the MLPA tests are sensitive to the quality of the DNA18 (AvdO, unpublished observations), deletion-specific PCRs were developed for diagnostic application of mutation analysis within the family, including prenatal testing. In all cases, three primers were used: one common primer, one primer located in the deleted region and one primer just outside the deletion (Table 1). The primers were chosen so that the fragment specific for the deletion was shorter than the wild-type fragment (Figure 4). Using the deletion-specific PCRs, the unaffected parents of patients 30 628, 21 722 and 14 249 tested negative for the deletion, suggesting that these patients are de novo TSC cases. Patients 1264 and 28 121 each had an affected family member. They were available for DNA deletion analysis and tested positive for the respective deletion-specific PCRs (Figure 4). The affected sib of patient 1264 showed mild mental retardation, epilepsy, cortical tubers and subependymal nodules (age of diagnosis 15 years). The mother of patient 28 121 had facial angiofibroma, ungual fibroma, fibrous plaques, hypomelanotic macules and shagreen patches (diagnosed at age 31 years). None of the healthy relatives tested positive for the familial deletions and, thus, non-penetrance was not encountered in these families. The parents of patient 31 457 were tested elsewhere by MLPA analysis. Both parents showed a normal result (data not shown). The parents of individuals 21 899 and 29 445 were not available for testing.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of the deletion PCR products. The identification number of the patients are indicated at the top of the figure. Abbreviations: *, deletion fragment; 0, wild-type fragment; C, negative control; F, father of the index patient; M, mother of the index patient; P, index patient; S, sibling of the index patient.

Clinical details

With one exception,20 no clinical information was available on the other previously reported TSC1 deletion cases. The clinical features of the nine TSC1 deletion index patients are summarised in Supplementary Table 3. All patients had a definite clinical diagnosis of TSC. The clinical findings of these nine TSC patients with TSC1 deletions were compared with other patients with a TSC1 mutation.3 Although the number of patients was very small, making comparisons difficult, fewer neurological symptoms and dermatological findings, especially shagreen patches, were found in the TSC1 deletion patient group (Supplementary Table 3; compare last two columns).

Discussion

In TSC patients, different types of mutations can be identified in TSC1 or TSC2. Approximately one-third are identified in TSC1.3, 4 Most of the pathogenic mutations are nonsense, frameshift or splice site mutations and some missense mutations have been described (http://chromium.liacs.nl/LOVD2/TSC/home.php). Recently, functional tests have helped to classify missense changes as pathogenic mutations in TSC1.23, 24, 25 So far, only a small number of large rearrangements in TSC1 have been described.18, 19, 20 In total, 16 large rearrangements, including the deletions described here, have been identified. In our cohort of individuals with a TSC2 mutation (487), an MLPA abnormality was present in 48 cases (9.9%; data not shown). In one case, an intragenic duplication of several exons was identified, whereas the other cases had (multiple) exon deletions. A TSC1 pathogenic mutation was present in 181 individuals (data not shown). Of these mutations, nine were large rearrangements (5.0%). The percentage large TSC1 rearrangements in the patient group of Kozlowski et al18 was lower (0.5% of all TSC1 mutations) compared with our group. In our cohort, all TSC1 and TSC2 rearrangements (n=57) account for 8.5% of all mutations (n=668). This is comparable with the data of Kozlowski et al (6.1% of all TSC mutations).

Of all 16 patients/families with a large TSC1 deletion, 5 patients were sporadic, 5 were familial cases and of the remaining 6 cases, the parents were not analysed by molecular techniques. In our previously described cohort of patients with point mutations in TSC1, a comparable ratio of sporadic with familial cases was observed (22 sporadic to 20 familial).3

As exon 1 is a non-coding exon, RNA analysis was performed to investigate the effect of deleting this exon on TSC1 mRNA expression. Monoallelic expression was demonstrated, indicating that exon 1 deletions are likely to be null alleles and that there is no alternative promoter present in the TSC1 region. Regulatory elements necessary for basal transcription of TSC1 and a region for optimal promoter function have been defined and were localised to the regions between nucleotide positions 16 271–16 003 and 16 002–15 683, respectively, upstream of the start codon in exon 3.9 In the UCSC Genome Browser only one promoter region is presented. A CpG island containing region and several transcription-binding sites are located in the same region as defined by the functional test and the monoallelic TSC1 expression in our patient. The promoter region was completely deleted in patients 30 628, 21 722 and 21 899. In patient 1264, a partial deletion of the promoter region was identified; only the most 5′ 155 nucleotides of the ‘basal’ transcription core were present. Unfortunately, this patient was not heterozygous for a coding SNP and therefore, it was not possible to analyse monoallelic expression of TSC1.

Three of the four exon 1 abnormalities were complex events (Figure 1 and Table 2). A combination of a deletion and an inversion was detected in two patients, whereas the abnormality in the third patient consisted of two deletions separated by 45 nucleotides and an insertion of unknown origin. It is not clear why exon 1 deletions account for almost half of the large TSC1 rearrangements in our cohort. Most deletions were not associated with specific repeat sequences and in only two cases a very short repeat sequence (two or three nucleotides) was observed. This is in contrast to the large rearrangements described in TSC2,18 wherein 70% of the abnormalities very short sequence repeats were present at the junction of the deleted segments.

Although genotype–phenotype comparisons with such a small number of TSC patients should be made with caution, the clinical phenotype of the patients with a TSC1 deletion was slightly less severe overall than that of patients with other TSC1 mutations. In addition, we noted that all patients with a deletion of exon 1 had epilepsy, whereas this was only observed in one of the five individuals with a deletion affecting other exons of TSC1. We demonstrated that deletions encompassing exon 1 are true null alleles. Therefore, one possible explanation for our observation is that the expression of truncated or mutant TSC1 isoforms may modify the TSC phenotype. Mutant TSC1 isoforms could either have a dominant negative effect by competing with wild-type TSC1 to form inactive TSC1–TSC2 complexes, or have a protective effect by retaining some functionality and maintaining some TSC1–TSC2 activity in the cell26 (M Nellist, unpublished observations).

In our cohort, 5.0% of all TSC1 mutations were identified using MLPA, indicating that it is necessary to screen for large TSC1 rearrangements in TSC patients. Although the number of patients identified with a large (complex) deletion is relatively small, it might be that these patients show less severe symptoms compared with patients with point mutations in TSC1.

References

Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP : The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 1345–1356.

Au KS, Williams AT, Roach ES et al: Genotype/phenotype correlation in 325 individuals referred for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex in the United States. Genet Med 2007; 9: 88–100.

Sancak O, Nellist M, Goedbloed M et al: Mutational analysis of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes in a diagnostic setting: genotype--phenotype correlations and comparison of diagnostic DNA techniques in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Eur J Hum Genet 2005; 13: 731–741.

Dabora SL, Jozwiak S, Franz DN et al: Mutational analysis in a cohort of 224 tuberous sclerosis patients indicates increased severity of TSC2, compared with TSC1, disease in multiple organs. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 68: 64–80.

Jones AC, Sampson JR, Hoogendoorn B, Cohen D, Cheadle JP : Application and evaluation of denaturing HPLC for molecular genetic analysis in tuberous sclerosis. Hum Genet 2000; 106: 663–668.

European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium: Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. Cell 1993; 75: 1305–1315.

van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C et al: Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science 1997; 277: 805–808.

Henske EP, Scheithauer BW, Short MP et al: Allelic loss is frequent in tuberous sclerosis kidney lesions but rare in brain lesions. Am J Hum Genet 1996; 59: 400–406.

Ali M, Girimaji SC, Kumar A : Identification of a core promoter and a novel isoform of the human TSC1 gene transcript and structural comparison with mouse homolog. Gene 2003; 320: 145–154.

Mayer K, Ballhausen W, Rott HD : Mutation screening of the entire coding regions of the TSC1 and the TSC2 gene with the protein truncation test (PTT) identifies frequent splicing defects. Hum Mutat 1999; 14: 401–411.

van Bakel I, Sepp T, Ward S, Yates JR, Green AJ : Mutations in the TSC2 gene: analysis of the complete coding sequence using the protein truncation test (PTT). Hum Mol Genet 1997; 6: 1409–1414.

Rendtorff ND, Bjerregaard B, Frodin M et al: Analysis of 65 tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) patients by TSC2 DGGE, TSC1/TSC2 MLPA, and TSC1 long-range PCR sequencing, and report of 28 novel mutations. Hum Mutat 2005; 26: 374–383.

Langkau N, Martin N, Brandt R et al: TSC1 and TSC2 mutations in tuberous sclerosis, the associated phenotypes and a model to explain observed TSC1/ TSC2 frequency ratios. Eur J Pediatr 2002; 161: 393–402.

Roberts PS, Jozwiak S, Kwiatkowski DJ, Dabora SL : Denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) is a highly sensitive, semi-automated method for identifying mutations in the TSC1 gene. J Biochem Biophys Methods 2001; 47: 33–37.

Brook-Carter PT, Peral B, Ward CJ et al: Deletion of the TSC2 and PKD1 genes associated with severe infantile polycystic kidney disease--a contiguous gene syndrome. Nat Genet 1994; 8: 328–332.

Verhoef S, Vrtel R, van Essen T et al: Somatic mosaicism and clinical variation in tuberous sclerosis complex. Lancet 1995; 345: 202.

Dabora SL, Nieto AA, Franz D, Jozwiak S, Van Den Ouweland A, Kwiatkowski DJ : Characterisation of six large deletions in TSC2 identified using long range PCR suggests diverse mechanisms including Alu mediated recombination. J Med Genet 2000; 37: 877–883.

Kozlowski P, Roberts P, Dabora S et al: Identification of 54 large deletions/duplications in TSC1 and TSC2 using MLPA, and genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Genet 2007; 121: 389–400.

Longa L, Saluto A, Brusco A et al: TSC1 and TSC2 deletions differ in size, preference for recombinatorial sequences, and location within the gene. Hum Genet 2001; 108: 156–166.

Nellist M, Sancak O, Goedbloed MA et al: Large deletion at the TSC1 locus in a family with tuberous sclerosis complex. Genet Test 2005; 9: 226–230.

Bruge F, Littarru GP, Silvestrini L, Mancuso T, Tiano L : A novel Real Time PCR strategy to detect SOD3 SNP using LNA probes. Mutat Res 2009; 669: 80–84.

Berggren P, Kumar R, Sakano S et al: Detecting homozygous deletions in the CDKN2A(p16(INK4a))/ARF(p14(ARF)) gene in urinary bladder cancer using real-time quantitative PCR. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9: 235–242.

Coevoets R, Arican S, Hoogeveen-Westerveld M et al: A reliable cell-based assay for testing unclassified TSC2 gene variants. Eur J Hum Genet 2009; 17: 301–310.

Nellist M, Sancak O, Goedbloed M et al: Functional characterisation of the TSC1-TSC2 complex to assess multiple TSC2 variants identified in single families affected by tuberous sclerosis complex. BMC Med Genet 2008; 9: 10.

Nellist M, van den Heuvel D, Schluep D et al: Missense mutations to the TSC1 gene cause tuberous sclerosis complex. Eur J Hum Genet 2009; 17: 319–328.

Mozaffari M, Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, Kwiatkowski D et al: Identification of a region required for TSC1 stability by functional analysis of TSC1 missense mutations found in individuals with tuberous sclerosis complex. BMC Med Genet 2009; 10: 88.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of the families for providing samples and cooperating with this study. Financial support for MN was provided by the US Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (grant no. TS060052).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van den Ouweland, A., Elfferich, P., Zonnenberg, B. et al. Characterisation of TSC1 promoter deletions in tuberous sclerosis complex patients. Eur J Hum Genet 19, 157–163 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.156

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.156

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Targeted Next Generation Sequencing reveals previously unidentified TSC1 and TSC2 mutations

BMC Medical Genetics (2015)

-

Tsc1 (hamartin) confers neuroprotection against ischemia by inducing autophagy

Nature Medicine (2013)

-

Multiplex ligation-depending probe amplification is not suitable for detection of low-grade mosaicism

European Journal of Human Genetics (2011)