An aerial view of glaciers near Svalbard Islands, in the Arctic Ocean in Norway.Credit: Sebnem Coskun/Anadolu Agency via Getty

Like many polar researchers, Julie Brigham-Grette is making up for time lost to the pandemic. In February 2020, within weeks of moving to Germany to begin an eight-month Humboldt Research Fellowship, the COVID-19 outbreak sent her back home to the United States. “Scientists like myself had to sever plans so quickly,” says Brigham-Grette, a geoscientist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, in Massachusetts.

She tried to make the most of the next two years. She wrote and edited a special volume of the Journal of Quaternary Science and brainstormed new projects. Using a different grant from the US National Science Foundation, she launched a collaboration with two villages in Alaska over Zoom to explore how her research priorities, and those of her colleagues, can be informed by the experience and knowledge of local Indigenous communities.

Nature Index 2023 Climate and conservation

By early 2022, as restrictions were easing around the world, polar scientists were eager to get back to work. “Everyone was on board to resume normal international collaborations and were ramping up for their big field seasons,” says Brigham-Grette. She was set to join a major international expedition to the Arctic Ocean, to collect sub-sea-floor samples that would allow the team to stitch together a full climatic record for the region spanning the past 2 million to 3 million years. “Everything was planned, and it was just going to be fantastic,” she says. “We’d finally get this amazing record.”

But then, on 24 February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, providing a major new challenge to the international science community, says Brigham-Grette.

The effects were especially pronounced in the Arctic, where Russia accounts for about half of the total territory. Brigham-Grette’s field trip was called off because the sampling site was too close to Russian waters. There were similar cancellations for countless other teams whose research depended on access to the Russian Arctic or collaborations with Russian partners.

Concerns are also growing over the consequences of Russia’s isolation from the international research community for global efforts to combat climate change. “In order to tackle some of the most important challenges facing the world at this moment, [we] need Russia to be working on climate-change issues like methane release and the thawing of permafrost in the Arctic,” says Evan Bloom, a senior fellow specializing in Arctic and Antarctic research at the Wilson Center, a think tank based in Washington DC.

Rush to recover

Although Russia as a research destination is out of reach for most, polar scientists are hustling to rekindle in-person collaborations elsewhere and return to the field. In the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, for example, “we’re back to as many scientists, or maybe more, than before the pandemic”, says Kim Holmén, a climate and environment scientist at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, in Tromsø.

Despite the enthusiasm, there have been difficulties in resuming research. Changes to key institutional and governmental staff, for example, have slowed efforts to get back on track. “There is always staff rotation, but because of the COVID gap, more people are unfamiliar with what the normal activities used to be,” Holmén says. “A loss of continuity and experience takes time to rebuild to achieve the same level of productivity.”

Funding deadlines have also lapsed, meaning researchers have to rewrite proposals and resecure grants, which for many teams are now more limited than before the pandemic. In the United States in June, the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Antarctic programme announced that various delays, due in part to ongoing COVID-19 protocols, have resulted in a “severe shortage” of logistics needed to support the backlog of deferred Antarctic research. Consequently, the NSF anticipates its Antarctic programme will be “significantly curtailed” for at least the next year. In general, the backlog of delayed research is creating a logistical bottleneck, says Daniela Liggett, a social scientist at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, who specializes in human engagement with the Antarctic. “We are limited in the capacity of what we can do in the Antarctic, including how many people we can accommodate or take into the field.”

The impact that missing or delayed data might have on polar science will vary by project. For some long-term monitoring studies that span decades, a gap of a year or two might not make such a difference for overall conclusions, Holmén says, whereas for other data sets, it can be a significant setback. For polar-bear monitoring programmes, for example, “when you miss a year or two, especially with the changes we’re seeing in the environment, that can be a pretty big deal”, says Geoff York, senior director of research and policy at Polar Bears International, a non-profit organization headquartered in Bozeman, Montana.

Just as important as restarting the research is rekindling relationships. Some scientists have managed to maintain or even expand their collaborative networks during the pandemic, in part because the turn to online communications and conferences removed barriers to entry such as travel, visas and expenses that normally prevent some researchers from meeting with international colleagues. “You were suddenly talking to all kinds of people who you may not have met before,” Liggett says.

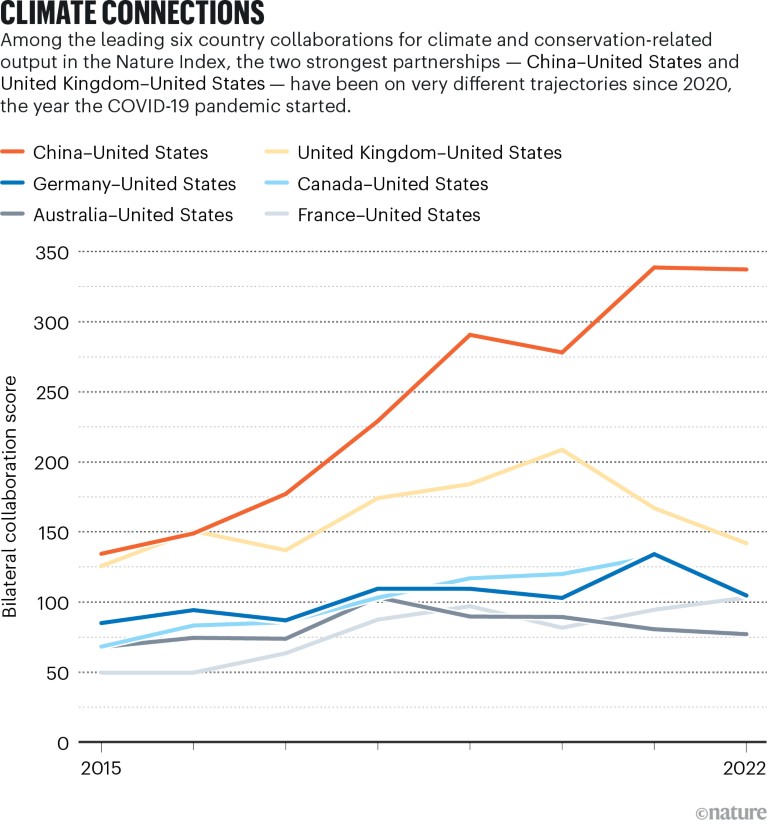

For others, though, the opposite occurred. York gets the impression that, on the whole, international and cross-disciplinary collaborations in polar-bear research took a significant blow. “I think a lot of people were just burned out,” he says. A number of polar-bear scientists were impacted by nonrefundable logistics investments such as aircraft contracts and fuel caching for remote work, and some began to reconsider their continued dedication to international research that, even in normal times, is often expensive, logistically and politically challenging, dangerous, and requires significant time away from home. “Some retired early, some shifted jobs and others focused on research closer at hand and perhaps with fewer collaborators because it was simply easier,” York says. Even with travel now possible, he adds, “my sense is we’re a little slow in reestablishing multilateral collaborations”. It is difficult to isolate data from the Nature Index on polar-bear research, but in general the trends in international collaboration for climate and conservation science as a whole since 2020 have also been mixed (see ‘Climate connections’).

Source: Nature Index

Researchers who work with communities face the additional task of rebuilding in-person relationships with local partners. Gregory Thiemann, an environmental scientist at York University in Toronto, Canada, is collaborating with three Indigenous communities in Ontario to better understand and mitigate conflict between humans and polar bears. The inability over the past several years to make in-person visits has caused the project to fall about four years behind, he says. When working with communities, says Thiemann, “you really need to have face-to-face communication to build relationships and trust”.

War’s long shadow

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine threatens to have an even greater and more long-lasting impact on Arctic research than the pandemic did. Whereas most countries and institutions have not issued explicit orders banning their scientists from collaborating with their Russian counterparts, “as a practical matter, it is extremely difficult”, says Bloom. For researchers in many countries, collaborating with Russian scientists risks being seen as inadvertently supporting the Russian government, which funds most of the country’s research, he says. And Russian scientists could be endangered if they seem to be working too closely with the West.

“As for cooperative work and contacts with colleagues from ‘unfriendly’ countries, officially they are frozen,” says Dmitry Nazarov, a geologist at the Russian Geological Research Institute in St Petersburg, Russia. “But unofficially, people keep in touch.”

Funding for science and conservation often dries up in times of war, but for now, government-funded research in the Russian Arctic is ongoing, Nazarov says. Even so, “studies in the Arctic have been damaged severely”, he says, because most foreign scientists can no longer access a significant chunk of the region.

Hiroyuki Enomoto, vice-director of Japan’s National Institute of Polar Research in Tokyo, is still in touch with his Russian colleagues. “But they cannot send any data, and we cannot offer a budget to collaborate on field work,” he says. The plan, for now, is for the two teams to continue working separately, in the hope that “in the future, the situation will be changed and the data can be connected”, says Enomoto.

Some researchers are trying to pivot by shifting their study area away from Russian territory. “Suddenly, we’ve got all kinds of German groups heading to Alaska and the Yukon [in Canada],” Brigham-Grette says. This won’t fix the overall problem of a divided Arctic, though. “If we or the Russian scientists are shut off to one or the other half of the Arctic, then neither of us can figure out what the heck is going on” to the region as a whole, Holmén says. “Everyone loses.”

International fractures

Research in the Antarctic was hit harder by the pandemic than the Arctic, but less so by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Nevertheless, there have been negative effects in Antarctica, especially in terms of international cooperation. Both Russia and Ukraine are decision-making parties to the Antarctic Treaty, an international agreement originally signed in 1959 that, among other things, promotes collaboration on issues such as species protection and tourism management on the continent. The fact that Russia and Ukraine are at odds “really strains everything”, Liggett says.

Russia’s blockade of the Port of Odessa, the largest Ukrainian seaport and one of the largest ports in the Black Sea basin, has prevented Ukraine from servicing its Antarctic field station. “Ukrainian Antarctic research has taken a huge hit,” Liggett says. When the war began, researchers from other countries had to step up to ensure that the 12 Ukrainian scientists who were in the field at the time “were given support and transport and weren’t stuck in Antarctica without food”, Liggett says.

Logistical complications have affected other research teams, too. Thamban Meloth, director of India’s National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research in Goa, and his colleagues, for example, have a contract with a Russian vessel based in South Africa for their transport to Antarctica. However, the helicopter on board the vessel, which the researchers also use, belongs to a Ukrainian company. “There have been very difficult issues to handle from a diplomacy standpoint,” says Meloth. The cost of transporting cargo from India to Antarctica has also increased by about 30% since the war began.

In some ways, it’s like relations with Russia have reverted back to the days before the Iron Curtain fell, says Enomoto. But there is one key distinction: researchers “have different mindsets now than they did in the Cold War”, he says, because they’ve seen what’s possible when international teams come together. Staying in touch with colleagues in Russia — and looking forward to a future when collaborations will be possible again — is a “very important effort for science”, Enomoto says.

Nazarov, in Russia, agrees: “All of us hope to go back to joint international projects one day.”

Climate and conservation science persevere in the face of major challenges

Climate and conservation science persevere in the face of major challenges

Three scientists on the front line of climate and conservation research

Three scientists on the front line of climate and conservation research

Achieving UN climate goals needs purposeful, persistent action from science

Achieving UN climate goals needs purposeful, persistent action from science

Where is the strongest research focus on the environment?

Where is the strongest research focus on the environment?