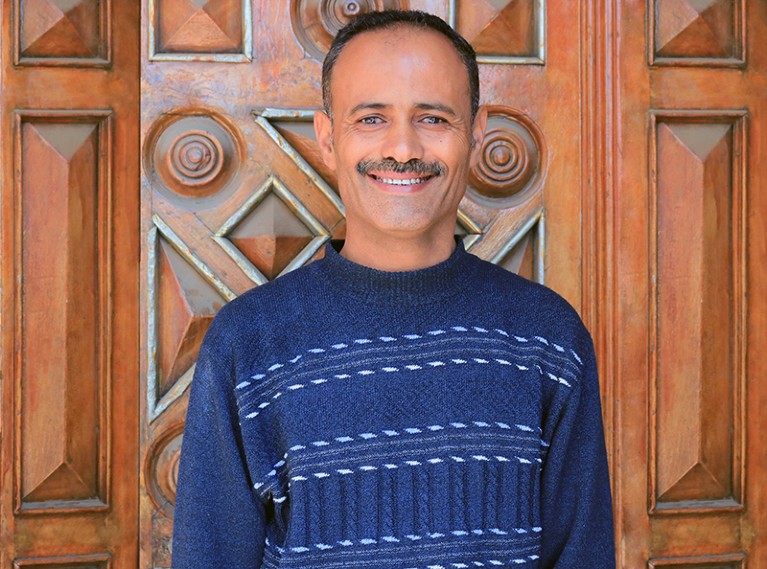

Geologist Fahd Albarraq has made many sacrifices to keep the Yemen Geological Museum open.Credit: Shihab Jamal

Yemeni geologist Fahd Albarraq manages the Yemen Geological Museum in Sana’a. In 2016, not long after civil war broke out, the country’s economy collapsed and the museum lost its permanent financing from the government. Albarraq and three of his colleagues reopened it, without pay, in 2017.

Tell us about the museum and your exhibits.

It’s a scientific museum that was founded in 1999 and obtained official recognition from the government in 2012, giving it national museum status. I’ve worked here for most of my professional life. Our main focus is on geology, thanks in part to our sponsors, the Yemen Geological Survey and Mineral Resources Board (YGSMRB). And, as well as our exhibits, we have a 140-seat lecture theatre, where we screen documentary films.

During the 2000s, we added more exhibits, such as snake fossils from the Jurassic period (201 million to 145 million years ago) and fish fossils from the Silurian period (443 million to 419 million years ago). There are also fossils of many types of mollusc and echinoderm, and of plants and trees from different geological periods. Almost all of the exhibits are from Yemen. We also show types of igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic rock, such as rhyolite, shale and gneiss.

Collection: Science careers and mental health

Since 2019, the YGSMRB has given volunteers US$20 per month to cover our commuting costs. Visitors can also donate to the museum.

What are the difficulties you face?

The suspension of salaries — which happened in 2016 as a result of the war — is our biggest problem. There were 12 of us before the conflict started, and only 4 have been able to return to the museum to work on a voluntary basis.

In 2019 we also lost our government funding. This meant we couldn’t pay for the museum’s website, so we were unable to share any news. We now depend on our Facebook page, which is free to run. Despite the financial difficulties, admission to the museum is still free and will remain so. Before the civil war broke out, the museum averaged around 60 visitors a day. By 2021, that number had increased to more than 140 a day, thanks to a combination of social media promotion and our encouraging school trips. The war itself is also a factor: people are looking for escape and distraction in science and art.

How has the war affected you personally?

Before the war, I lived in comfort. As a geology student at Sana’a University between 1997 and 2001, I worked in a fast-food restaurant after classes. The wages were enough to live a good life because prices were low, and I could send money to my father, who lives in a Yemeni mountain village. In 2002, I got the job at the museum and was able to save money easily. I got married the following year, and a few years later bought a car.

Now, I borrow money from many people. I’m burdened by a monumental amount of debt. I have two daughters and two sons, aged from 6 to 16, and I have sold my car and my wife’s jewellery to pay their school fees.

The war threatens our safety and our financial situation. Killing and destruction is everywhere. The most awful thing is the intense air raids on Sana’a, where we live. I worry that I can’t do anything to make my family feel safe.

Why do you still volunteer at the museum?

This museum is an important part of my life. When a person works in a field they love, they sacrifice a lot to stay in that job. I wouldn’t be comfortable with another job outside the field of earth sciences.

Working at this museum makes me feel that I am doing something worthwhile. After I finish my work at the museum, I go to my uncle’s small mobile-phone shop. He gives me wages that help me meet some family expenses. It’s hard to consider it a good opportunity, but it allows me to keep working at the museum.

Lessons learnt from doing research amid a humanitarian crisis

Lessons learnt from doing research amid a humanitarian crisis

Death, statistics and a disaster zone: the struggle to count the dead after Hurricane Maria

Death, statistics and a disaster zone: the struggle to count the dead after Hurricane Maria

How museum work can combine research and public engagement

How museum work can combine research and public engagement