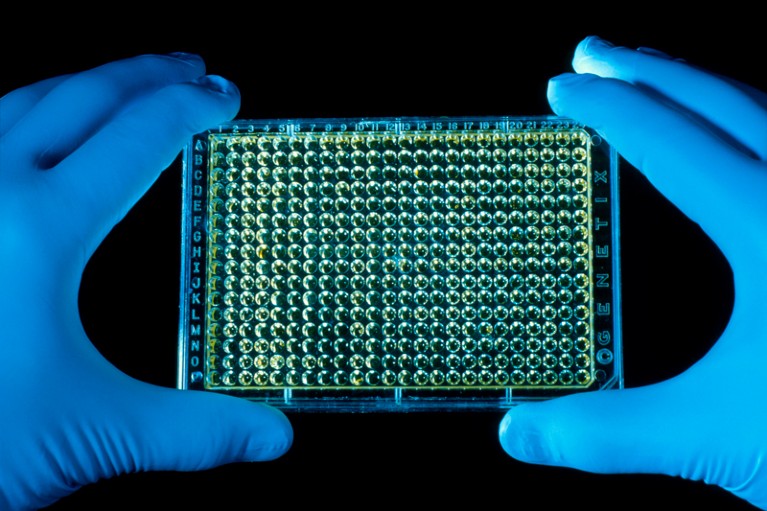

A tray containing part of a human genome. The wells each hold a different fragment of cloned DNA.Credit: James King-Holmes/Science Photo Library

The first drafts of the human genome, published in Nature and Science 20 years ago, flung open the doors for what some predicted would be ‘biology’s century’. In just one-fifth of the century, the corpus of information has grown from two gappy and error-filled genome sequences to a full account of the genetic variation of hundreds of thousands of individuals around the world, and an increasing number of tools to study it. This special issue of Nature examines how far the human genome sequence has taken us, and how far we have to go. But some aspects of the research ecosystem around the human genome have hardly changed, and that remains a concern.

Many of the ethical, legal and social implications of genome research — including questions of privacy, informed consent and equitable representation of researchers and participants — remain unresolved. Moreover, free and open access to genome data remains unevenly implemented. Just this week, researchers pointed out the problems caused by lack of accessibility to coronavirus genomes in the middle of a pandemic. Researchers, funders and journals will need to address these issues if they are to fulfil the promises of the Human Genome Project and to better understand diseases and improve diagnoses and treatments.

The broken promise that undermines human genome research

The draft genome sequence published in Nature was immediately free to access — in fact, the initial assembly was posted online some seven months beforehand. This was in accordance with the Bermuda Principles, an agreement on data sharing signed by members of the international consortium that made the Human Genome Project possible.

Nature committed to open-data principles for genomics research back in 1996. By publishing the Human Genome Project’s first paper, we worked with a publicly funded initiative that was committed to data sharing. But the journal acknowledged there would be challenges to maintaining the free, open flow of information, and that the research community might need to make compromises to these principles, for example when the data came from private companies. Indeed, in 2001, colleagues at Science negotiated publishing the draft genome generated by Celera Corporation in Rockville, Maryland. The research paper was immediately free to access, but there were some restrictions on access to the full data.

Twenty years later, compromises and delays are becoming the norm in three domains of genome research: data collection from participants; deposition in approved, publicly accessible databases; and access for research and health care. The promise of a fully open data-sharing environment has not yet been realized.

A wealth of discovery built on the Human Genome Project — by the numbers

For genomics to truly revolutionize medicine, it needs to be combined with phenotypic data — physical characteristics, medical histories and other identifiable traits that can be linked to variants in the genome. But collecting such data increases privacy risks for research participants, who are now rightly being given more control, such as choosing how their data will be used. Moreover, scientists involved need to be vetted to ensure that participants have given the appropriate consent and that their interests are protected.

The next step is to deposit the collected genome sequences and the accompanying data into approved international databases that can continue to protect those interests. But researchers regularly report being unable to deposit their data quickly, citing privacy and consent concerns, or agreements with companies that have contributed data. Technological limitations mean that the process of depositing data can also be extremely time-consuming. Scientists are producing increasing volumes of ever more complex data — and this is overwhelming under-resourced repositories.

Finally, researchers struggle to track down data that should be available as soon as the accompanying research is published. And even after locating the data, they can find it hard to access them.

Diversity deficit

In the years since the Human Genome Project published its first draft sequence, researchers have recognized that genome databases over-represent DNA from people of European descent who live in high-income nations.

Truly global databases and repositories need data that properly represent humanity’s vast genetic diversity. That this has not been achieved in two decades is a reminder of science’s history of mistreatment and neglect, particularly of African people and Indigenous populations. Many people from these communities are understandably wary of participating in research that they regard as having little chance of benefiting them, and even some chance of causing harm. For example, when diseases are associated with a particular population, it can result in stigma and discrimination.

Sequence three million genomes across Africa

A committee of researchers convened by the African Academy of Sciences is urging international funders to take more account of the needs and wishes of those who contribute their data to genomics. That includes informed-consent agreements that are better tailored to specific research purposes, instead of the broad consent that is often requested. Ultimately, the best way forward is for this research to be performed by teams with people from many communities, all with an equal share in the process and an equal stake in the outcomes.

At this milestone anniversary, the genomics community — including funders, journals, researchers and participants from around the world — needs to recommit to open data sharing. At the same time, researchers must work in closer partnership with participants — devoting more time to engaging, building trust, listening and acting on concerns. This must be seen as a necessary part of genomics research, and will be key to its future.

Commitments are also needed to improve the standards for data repositories. The repositories must be made more accessible and less onerous to contribute to. Moreover, their governance needs to better reflect diverse perspectives, not only of the global genomics research community, but also of those whose data are being accessed.

As has been seen repeatedly during the pandemic, rapid data sharing can provide massive benefits to science and, through science, to all of society. It’s time to shore up that foundation and improve sharing practices — but always with equity and respect.

The broken promise that undermines human genome research

The broken promise that undermines human genome research

A wealth of discovery built on the Human Genome Project — by the numbers

A wealth of discovery built on the Human Genome Project — by the numbers

Sequence three million genomes across Africa

Sequence three million genomes across Africa

Breaking through the unknowns of the human reference genome

Breaking through the unknowns of the human reference genome

How the human genome transformed study of rare diseases

How the human genome transformed study of rare diseases

From one human genome to a complex tapestry of ancestry

From one human genome to a complex tapestry of ancestry

Milestones in genomic sequencing

Milestones in genomic sequencing

Scientists call for fully open sharing of coronavirus genome data

Scientists call for fully open sharing of coronavirus genome data

How diplomacy helped to end the race to sequence the human genome

How diplomacy helped to end the race to sequence the human genome

Global lessons from South Africa’s rooibos compensation agreement

Global lessons from South Africa’s rooibos compensation agreement

Santa Fe 1986: Human genome baby-steps

Santa Fe 1986: Human genome baby-steps