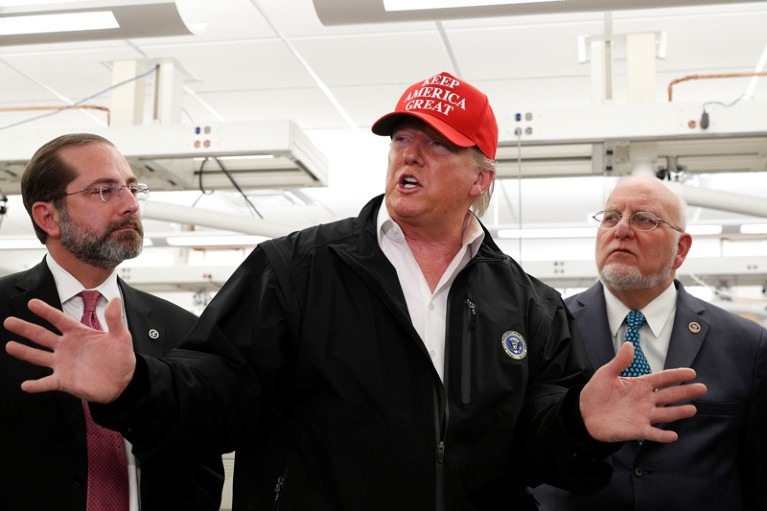

Researchers are questioning why Donald Trump chose to remove COVID-19 data management from the CDC and transfer it to the federal government.Credit: Tom Brenner/Reuters

As deaths from COVID-19 approach 150,000 in the United States and cases continue to rise alarmingly in many regions of the country, there are strong signs that the government is suppressing a public-health approach to controlling the pandemic.

Earlier this month, the administration of President Donald Trump chose to transfer responsibility for coronavirus data collection, management and sharing. This task, previously within the remit of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) — the public-health agency respected around the globe for collecting and analysing disease-surveillance data — was handed to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). This is the CDC’s parent institution, and its head, Alex Azar, is answerable to the president.

The change, implemented on 10 July, has caused confusion, both in hospitals and among public-health departments that work to provide data to the CDC. Measures must be implemented immediately to ensure that the transition is managed in an open and science-friendly way, and that politicians do not use the change to bypass researchers and sway the public-health response to the pandemic to suit their narrative. Many say that the Trump administration has tried to do this repeatedly throughout the pandemic.

The new data system is being run by TeleTracking Technologies, a company based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on behalf of the HHS. The HHS says the system is designed to modernize coronavirus data management and will provide a more thorough nationwide picture of the outbreak. Along with recording coronavirus cases from hospitals, the HHS says its ‘ecosystem’ of databases includes information on hospital supplies, diagnostic testing data and demographic statistics.

Researchers agree that the CDC’s public-health data-reporting system needed modernizing. For years, the agency has been asking for resources to update the systems it uses to track outbreaks ranging from Salmonella to antibiotic-resistant infections. But epidemiologists and public-health specialists interviewed by Nature have said that these improvements should have happened inside the CDC. The agency employs more than 1,000 epidemiologists who specialize in analysing public-health data. It will fall to them to monitor how the coronavirus continues to affect people in the years to come.

Meanwhile, hospitals and public-health departments don’t know who to report different kinds of COVID-19 data to, says Georges Benjamin, head of the American Public Health Association.

Coronavirus is spreading under the radar in US homeless shelters

When a person tests positive for COVID-19, there might be other valuable information recorded alongside the test result, such as their postal code, race and ethnicity, as well as any other medical conditions they have. It’s not clear to hospital data managers whether this additional information still needs to be reported to public-health departments, or through TeleTracking. As a result, Benjamin worries that some of this information might no longer get recorded. Race and ethnicity are already being under-reported for COVID-19 in most states. That’s a problem, because such data allow health departments to target interventions — and let them know if such measures are working.

It is unlikely that the change will be undone, because the new system is already in use. Indeed, hospitals had little choice but to use it, because those that don’t comply are at risk of losing their allocations of remdesivir, the antiviral drug that has had some success in treating the most serious cases of COVID-19. As of last week, more than 4,000 hospitals — out of the US total of about 6,200 — had sent data through the new portal.

That’s why it is essential that the HHS ensures that the new system is accessible to epidemiologists — at the CDC, in public-health departments and at universities. Moreover, the data must include more than just case numbers, treatments and hospital capacity. Equally important are data that can be used to monitor local outbreaks, such as the location of patients, and whether they had known contact with someone infected.

The HHS has said that the CDC has access to the data. But it is not clear whether the CDC will be able to interrogate the data according to its needs, or share its analyses with the public in a timely manner — a necessary process for the results to be acted on.

The White House factor

Why did the Trump administration decide to remove the CDC from its job in leading data surveillance, rather than modernizing the agency’s data-collection system? Jose Arrieta, the HHS chief information officer, and CDC director Robert Redfield have welcomed the transition of responsibilities as a way of cutting down on duplication and making data available more quickly than in the former system. But that still doesn’t answer the question of why these changes couldn’t have happened within the CDC. Neither the HHS nor the CDC responded to Nature’s requests for an interview.

What we do know is that this is not the first time the Trump administration has bypassed the CDC’s researchers, acted contrary to the agency’s advice, or compelled it to change that advice.

On 25 February, Nancy Messonnier, the CDC’s head of immunization and respiratory diseases, warned that the coronavirus would spread in communities in the United States.. Both Trump and Azar publicly refuted this, and the following day Trump appointed US vice-president Mike Pence to the head of a national coronavirus task force that would see the CDC playing a less prominent part in the pandemic response.

Until recently, Trump has refused to wear a face mask in public, contrary to the CDC’s advice that people should wear a cloth face covering to slow coronavirus transmission. At the start of this month, Trump again clashed with the CDC by calling its guidance on how schools can safely reopen too stringent. “I will be meeting with them!!!” he warned in a tweet. Two weeks later, the CDC published new guidance that stresses that COVID-19 poses a relatively low risk to school-aged children.

In a comment article in The Washington Post, four of the CDC’s former directors said that the schools controversy is an example of how “repeated efforts to subvert sound public health guidelines introduce chaos and uncertainty while unnecessarily putting lives at risk”.

Sudden changes to how data are reported could be deadly in an outbreak. That is why the HHS must immediately make contact with data managers at hospitals and public-health departments, and work with them to end the confusion over the new system.

Moreover, the HSS must make the data available to epidemiologists at public-health departments and universities so that they are able to work with this information, as they have done in the past. These researchers help local leaders to understand where the outbreak is spreading, and how to control it. Without their crucial work, the United States will continue to fight the pandemic blindly, through intermittent surges followed by economically destructive lockdowns.

Coronavirus is spreading under the radar in US homeless shelters

Coronavirus is spreading under the radar in US homeless shelters

How to address the coronavirus’s outsized toll on people of colour

How to address the coronavirus’s outsized toll on people of colour

US universities are right to fight injustice

US universities are right to fight injustice