More prenatal tests are on the way — but are we ready?Credit: Tim Hale/Getty

There is perhaps no greater consumer of information than an expecting parent. Details abound about pregnancy, delivery, infant care and feeding, developmental milestones, and parenting philosophies. All are available to learn — and obsess over, for those so inclined.

That pool of information is now being topped up by a steady drip of genetic data. In coming years, as non-invasive methods of prenatal genetic testing become more sophisticated and expansive, that drip could become a flood. We need to prepare.

Perhaps the biggest priority should be the latest generation of techniques that sample snippets of fetal DNA found floating in a mother’s blood. In some countries, the tests are increasingly being used to look for large chromosomal abnormalities, such as the extra copy of chromosome 21 that causes Down’s syndrome. Such screening tools can reduce the use of more invasive tests, such as amniocentesis and chorionic villi sampling, which carry a small risk of miscarriage.

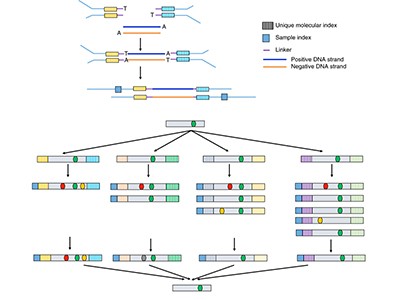

As the methods for isolating and sequencing such DNA improve, clinicians can gain information about more and more genetic disorders before birth. A study published this week (J. Zhang et al. Nature Med. http://doi.org/cz4m; 2019) demonstrates how far the technology has come — and where it is heading — by describing a test that can screen for 30 spontaneously arising single-gene disorders.

The group tested it on 422 samples from 131 clinics around the world. Some of the samples came from pregnancies with abnormal ultrasound findings, or a family history of disease. Others had no indication of trouble ahead. Thirty-two tested positive for a genetic disorder.

The team was able to follow up on outcomes from 233 of these pregnancies and found no false positive or false negative results among those for which diagnostic data were available. But the test would need to be repeated on a grander scale to nail down the risks that would come with positive findings, and to establish who would benefit most from the technology.

The expansion of non-invasive prenatal tests seems inevitable. This can benefit both parents and children. Prenatal testing could allow prospective parents and medical teams to prepare for the needs of the newborn, or, in some cases, to make the difficult decision to end a pregnancy. Many expectant parents welcome such tests. A survey of 186 women in the United States found that 83% thought prenatal tests that sequence all of the genome’s protein-coding genes should be offered (E. J. Kalynchuk et al. Prenat. Diagn. 35, 1030–1036; 2015). Such thorough sequencing of circulating fetal DNA is too complex and expensive to be practical at present, but it will become easier and cheaper in the future.

Still, prenatal screening based on circulating fetal DNA rarely offers definitive diagnoses: it must often be followed up by other tests to confirm the result, so parents can end up worrying unnecessarily. Furthermore, the effects of some disease-associated genetic variants could be masked by other variants elsewhere in the genome, or by environmental factors. Both of these factors mean additional, sometimes invasive, tests are often needed to back up genetic findings — and in many cases, genetics alone will never offer a clear indicator of disease risk.

Researchers and clinicians must adapt to the changes that such tests will bring. Widespread use will increase demand for trained genetic counsellors, who are already in short supply. Efforts to educate physicians and patients will need to be expanded, and the costs of counselling will need to be included in price estimates for implementing the tests.

Meanwhile, clinicians, researchers, ethicists and the public need to come together to develop guidelines about when such testing should be deployed and for which conditions, and how the information should be handled once the results are in.

Read the paper: Non-invasive prenatal sequencing for multiple Mendelian monogenic disorders using circulating cell-free fetal DNA

Read the paper: Non-invasive prenatal sequencing for multiple Mendelian monogenic disorders using circulating cell-free fetal DNA

Prenatal gene therapy offers the earliest possible cure

Prenatal gene therapy offers the earliest possible cure

A simple test helps pinpoint a baby’s arrival date

A simple test helps pinpoint a baby’s arrival date

Autism and DDT: What one million pregnancies can — and can’t — reveal

Autism and DDT: What one million pregnancies can — and can’t — reveal