Abstract

Background:

Patients treated with (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab who relapse and receive trastuzumab for metastatic breast cancer (MBC) are a growing population with little outcome data given their exclusion from most clinical trials. We aim to estimate survival outcomes for this trastuzumab ‘pre-treated’ population.

Methods:

Population-based study of Australian women receiving trastuzumab for HER2-positive MBC between 2006 and 2014, who also received (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab. We used Kaplan–Meier methods to estimate the following: overall survival (OS) from initiation of trastuzumab for MBC; duration of trastuzumab for MBC; and time from last (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab to first trastuzumab for MBC.

Results:

Of 3199 patients dispensed trastuzumab for MBC, 634 (20%) had received (neo)adjuvant traztuzumab. Pre-treated patients had a median (interquartile range) OS of 21.8 months (10.9–51.6), trastuzumab duration of 12.8 months (4.7–17.5), and time from last (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab to first trastuzumab for MBC of 15.6 months (6.5–28.6). Median OS for patients initiating trastuzumab <12 months and ⩾12 months from their last (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab were 17.1 months and 24.8 months, respectively.

Conclusions:

Patients starting trastuzumab for MBC following (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab had a median treatment duration of 1 year and OS of almost 2 years. These data help inform clinical practice and service planning for this under-researched population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Trastuzumab (Herceptin, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA, USA; Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) is standard of care for HER2-positive breast cancer. Randomised clinical trials of cancer treatments estimate progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), and inform policy makers in their decisions to register cancer medicines for marketing and subsidise treatment costs. In practice, these estimates also inform risk/benefit ratios to guide treatment selection and provide evidence to oncologists and patients about expected survival gains from treatment. However, trial patients are relatively homogeneous, unlike the populations treated in routine clinical care. As such, trial estimates have limited applicability to the real-world seting.

To date, we have very limited trial data on the outcomes for patients initiating trastuzumab for early breast cancer (EBC), who relapse and again receive trastuzumab for metastatic breast cancer (MBC) (Cardoso et al, 2012). This is due in part to the sequence in which breast cancer medicines are trialled – first in MBC, then EBC – as well as the fact that many clinical trials involving trastuzumab in the metastatic setting have excluded patients pre-treated with trastuzumab for EBC or those relapsing within 6 or 12 months of their last dose of trastuzumab for EBC.

Since the publication of the HERA (Piccart-Gebhart et al, 2005) and N9831/B-31 (Romond et al, 2005) trial outcomes, and the widespread use of trastuzumab for EBC, there have been over 15 trials involving trastuzumab for MBC, but only 2 have reported specific PFS estimates for patients who received prior (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab (Baselga et al, 2012; Perez et al, 2017). Currently, no trials have reported OS estimates for this growing population.

Two single arm, prospective clinical trials each with <45 patients (Lang et al, 2014; Xu et al, 2016) and several pubished observational studies, with ∼150 patients or less, have reported outcomes for trastuzumab-treated patients in both early and late stage disease (Gruschkus et al, 2010; Krell et al, 2011; Spano et al, 2012; Murthy et al, 2014; Negri et al, 2014; Lambertini et al, 2015; Rier et al, 2017). Four observational studies directly compared the survival ouctomes of these patients with patients who were trastuzumab-naive at the start of metastatic therapy; one found significant differences in survival between the groups (longer survival in the trastuzumab-naive patients) (Murthy et al, 2014; Negri et al, 2014; Lambertini et al, 2015; Rier et al, 2017). However, the patient groups compared in these studies were substantially different before the initiation of metastatic treatment. Although the studies did adjust for relevant clinical factors in their analyses, it is difficult to disentangle treatment effects from underlying patient differences (both measured and unmeasured) at the commencement of treatment, an inherent challenge in real-world effect studies.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe the survival outcomes and patterns of treatment for a large, population-based cohort of patients treated with trastuzumab for both EBC and MBC. We report OS from initiation of trastuzumab for MBC, the duration of trastuzumab in the metastatic setting and the time from cessation of trastuzumab for EBC until initiation of trastuzumab for MBC. We further examine these outcomes in patient subgroups initiating trastuzumab for MBC within and >12 months from cessation of (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab. We also report outcomes of patients who were naive to trastuzumab at initiation of metastatic therapy.

Patients and methods

Setting and data sources

The Australian healthcare setting and the datasets used in this study have been described in detail in our research protocol (Daniels et al, 2017). Briefly, Australia maintains a publicly funded, universal healthcare system entitling all citizens and permanent residents to subsidised prescribed medicines through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). The Herceptin Program, separate to the PBS, provided fully subsidised access to trastuzumab for MBC from December 2001 until July 2015, when the programme was closed and trastuzumab for MBC was PBS listed. Adjuvant trastuzumab was PBS listed from 1 October 2006 and neoadjuvant trastuzumab from 1 December 2012. The prescribing requirements across all three settings mimicked those of the clinical trials and are detailed in our research protocol (Daniels et al, 2017).

The Australian Department of Human Services (DHS) supplied de-identified, patient-level data including patient information (year of birth, month/year of death, weight at commencement of metastatic trastuzumab), and dispensing dates for trastuzumab (Herceptin Program records for metastatic disease and PBS records for early stage disease) and all PBS-listed chemotherapeutic, hormonal and other prescribed medicines (Daniels et al, 2017). As fact of death data were supplied in month and year of death format, we set date of death at the last day of the month in which a patient died. Australian Department of Human Services supplied data for the period 1 January 2001 to 31 March 2014. Patients without a fact of death record whose PBS and MBS records ended at least 181 days before 31 March 2014 were considered to have incomplete records and were excluded from our analyses.

Study population and subgroups

Our study population includes every Australian woman initiating trastuzumab for MBC subsidised through the Herceptin Program between 1 October 2006 and 31 March 2014 (data censor date). In Australia, once a medicine is subsidised through a national scheme, the Commonwealth bears the cost of the medicine for the subsidised indication. Therefore, it would be extremely unlikely that women with this indication would access the medicine through other payment mechanisms such as out-of-pocket. As such, our study population likely captures the actual population of patients treated with trastuzumab in Australia during the study period. We excluded patients initiating trastuzumab for MBC before 1 October 2006, as these patients had no opportunity to receive PBS-funded trastuzumab for EBC. Moreover, patients initiating trastuzumab from this time point are more likely to represent those treated in contemporary practice, where trastuzumab is available for EBC and MBC.

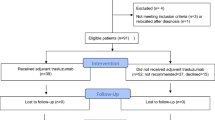

We identified two main cohorts of women accessing trastuzumab for MBC through the Herceptin Program (Figure 1):

-

1)

‘Trastuzumab pre-treated’: patients with at least one PBS-funded trastuzumab dispensing for EBC (adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy) before initiating trastuzumab for MBC through the Herceptin Program. We further stratified this cohort into two subgroups:

-

a

patients initiating trastuzumab for MBC <12 months from their last (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab dispensing.

-

b

patients initiating trastuzumab for MBC ⩾12 months from their last (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab dispensing.

-

a

-

2)

‘Trastuzumab-naive’: patients who did not receive PBS-listed traztuzumab for EBC. We further stratified this cohort into two subgroups:

-

a

Patients initiating trastuzumab for MBC through the Herceptin Program within 90 days of their first dispensing of any cancer medicine (chemotherapy or endocrine therapy). We considered this definition a proxy for those diagnosed with de novo MBC.

-

b

Patients initiating trastuzumab for MBC more than 90 days after their first dispensing of any cancer medicine (chemotherapy or endocrine therapy). These patients may have been previously treated for EBC or MBC without traztuzumab.

-

a

To avoid misclassification of instances where occult metastatic disease was present at EBC diagnosis, patients whose first dispensing of trastuzumab for MBC occurred within 90 days of their first dispensing of trastuzumab for EBC were assigned to the trastuzumab-naive cohort. This approach has been used previously (Yardley et al, 2014).

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics

We reported patient age and weight at the time of initiation of trastuzumab for MBC and used a validated proxy to determine hormone receptor (HR) status based on dispensing records from the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification category L02 (Srasuebkul et al, 2014). This proxy requires an observation period of at least 1 year before initation of the treatment of interest to accurately determine HR status. As such, we only estimated HR status for trastuzumab pre-treated patients, for whom we have this prior observation period. We calculated the median follow-up time from initiation of trastuzumab for MBC according to the reverse Kaplan–Meier method (Schemper and Smith, 1996). For trastuzumab pre-treated patients, we calculated the interval between the last trastuzumab dispensing for EBC until the first trastuzumab dispensing for MBC and used the Kaplan–Meier estimator to calculate the median and interquartile range (IQR). We identified concomitant taxane dispensings in PBS records.

Overall survival

We used the Kaplan–Meier estimator to calculate OS for both cohorts and all subgroups as the time from the first dispensing date of trastuzumab for MBC until date of death from any cause or censor (31 March 2014). We also stratified survival estimates by HR status for trastuzumab pre-treated patients. We did not directly compare survival outcomes between cohorts stastistically as we do not have clinical data and cannot control for inherent differences between the cohorts that would impact on our outcomes of interest.

Duration of trastuzumab

For trastuzumab pre-treated patients, we estimated duration of (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab as the period from the first (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab dispensing until the last dispensing before initiating trastuzumab for MBC, plus 30 days, or the number of days until metastatic trastuzumab initiation (if less than 30 days). We estimated the duration of trastuzumab in the metastatic setting as the period from first dispensing of trastuzumab for MBC until the last dispensing of trastuzumab for MBC, plus 30 days, or death, whichever occurred first. We considered a period of more than 90 days between dispensing records as a break in treatment, and a dispensing following a break of more than 90 days as a new course of therapy. We estimated the median duration of trastuzumab for MBC using Kaplan–Meier methods and excluded any treatment breaks.

Chemotherapy

We used PBS dispensing records to determine which patients started trastuzumab (for EBC and MBC) with a taxane, with non-taxane chemotherapy, or as monotherapy. We determined the number of distinct chemotherapies dispensed following initiation of trastuzumab for MBC as a proxy for the number of lines of therapy patients received in the metstatic setting.

Ethics and data access approvals

Our study was approved by the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (Approval Number: 2010/02/213) and data access was granted by the Australian DHS External Request Evaluation Committee (approval numbers: MI1474, MI1475 and MI1477). Individual consent for the release of these data has been waived according to the Australian Privacy Act of 1988 (Daniels et al, 2017).

Results

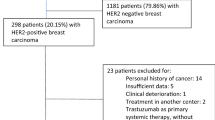

We identified 3199 patients who started trastuzumab for MBC between 1 October 2006 and 31 March 2014. Six-hundred and thirty-four (20%) patients had been prescribed trastuzumab for EBC, whereas 2565 (80%) patients were trastuzumab-naive. Median age was 56 years and 59 years for trastuzumab pre-treated and trastuzumab-naive patients, respectively (Table 1). There were 626 (99%) trastuzumab pre-treated patients with at least 1 year of observation time before initiation of trastuzumab for MBC and 321 (51%) of these patients were identified as HR-positive. With a median follow-up time of 41.6 months (IQR: 20.8–66.3) from first dispensing of trastuzumab for MBC, 53% of trastuzumab pre-treated patients and 52% of trastuzumab-naive patients have died.

Among trastuzumab pre-treated patients, the median time from last trastuzumab dispensing for EBC until first trastuzumab dispensing for MBC was 15.6 months (IQR: 6.5–28.6) (Table 1); 257 (40%) commenced trastuzumab for MBC within 12 months of ceasing trastuzumab for EBC (Supplementary Appendix Table A). Patients initiating trastuzumab <12 months or ⩾12 months from (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab cessation were similar in age, though patients initiating trastuzumab for MBC <12 months from (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab had a lower proportion of HR-positive disease (47 vs 58%) and a greater proportion of deaths (65 vs 45%).

Among trastuzumab-naive patients we classified 1615 (63%) with de novo MBC, whereas 950 (37%) had received non-trastuzumab cancer therapy before starting trastuzumab for MBC. Patients in these subgroups had similar characteristics though a higher proportion of patients with previous non-trastuzumab cancer therapy died in the follow-up period compared to the de novo trastuzumab-naive patients (63% vs 46%) (Supplementary Appendix Table A).

Overall survival

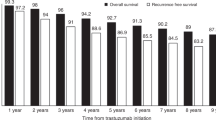

In trastuzumab pre-treated patients, median OS from initiation of trastuzumab for MBC was 21.8 months (IQR: 10.9–51.6). Patients initiating trastuzumab for MBC <12 months after ceasing (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab had a median OS of 17.1 months, whereas those initiating trastuzumab for MBC ⩾12 months after ceasing (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab had a median OS of 24.8 months (Figure 2, Supplementary Appendix Figure B). In trastuzumab-naive patients, median OS was 35.6 months (IQR: 16.0–79.8) (Figure 2, Supplementary Appendix Figure B). Hormone receptor-positive trastuzumab pre-treated patients had a median OS of 26.5 months, whereas HR-negative trastuzumab pre-treated patients had a median OS of 16.6 months (Supplementary Appendix Figure C).

Median (IQR) overall survival and duration of metastatic trastuzumab therapy, in months, from first dispensing of trastuzumab for MBC. Kaplan–Meier survival probability plots are provided in Supplementary Figure A.

Trastuzumab duration

In trastuzumab pre-treated patients, median duration of trastuzumab for MBC was 12.8 months (IQR: 6.0–31.5) (Figure 2). Duration of trastuzumab for MBC was 9.5 months for patients initiating trastuzumab for MBC <12 months after ceasing (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab and 14.8 months for patients initating trastuzumab for MBC ⩾12 months after ceasing (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab. In trastuzumab-naive patients, median duration of trastuzumab was 18.6 months (IQR: 8.7–41.8).

Chemotherapy

In trastuzumab pre-treated patients, most initiated trastuzumab with a taxane in both the (neo)adjuvant (67%) and metastatic settings (60%; Table 1 and Supplementary Appendix Table B). The median number of chemotherapies dispensed to trastuzumab pre-treated patients in the metastatic setting was two (IQR: 1–3; Table 1 and Supplementary Appendix Table A). Similarly, in trastuzumab-naive patients, most (66%) initiated trastuzumab with a taxane and received a median of two chemotherapies (Table 1).

Discussion

In this large, population-based cohort study, we report the real-world survival estimates for Australian women with HER2-positive MBC with a particular focus on trastuzumab pre-treated patients who are not well represented in clinical trials. Our median OS estimate for trastuzumab pre-treated patients of 21.8 months is shorter than (Lang et al, 2014; Murthy et al, 2014; Negri et al, 2014; Lambertini et al, 2015) and similar to (Krell et al, 2011; Metzger-Filho et al, 2016; Rier et al, 2017) those reported in studies involving substantially smaller cohorts. The median OS for pre-treated patients is also substantially shorter than that for trastuzumab-naive patients starting trastuzumab for MBC (35.6 months). However, it is not possible to ascertain the exact impact of treatment on the survival differences given the inherent differences between these groups of patients.

Although OS estimates for the trastuzumab pre-treated patients are not yet reported from the recent MARIANNE trial (Perez et al, 2017) and were not reported for the CLEOPATRA trial (Swain et al, 2015), our estimated duration of metastatic trastuzumab for pre-treated patients (12.8 months) was similar to the median PFS estimates reported for trastuzumab pre-treated patients in the control arms (trastuzumab and taxane chemotherapy) of these trials – 10.3 months (Perez et al, 2017) and 10.4 months, respectively (Baselga et al, 2012). Our data do not allow us to determine the time of disease progression; however, given most patients in the trastuzumab pre-treated and trastuzumab-naive subgroups received two different chemotherapies after starting trastuzumab for MBC, it is likely to be that clinicians were changing the chemotherapy partner at the time of progression but continuing trastuzumab.

The evidence generated in this real-world study can support oncologists, patients and policy makers to better estimate survival for patients starting HER2-targeted therapy for MBC. Currently, the standard first-line treatment for HER2-positive MBC is the combination of trastuzumab, pertuzumab (Perjeta, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA, USA; Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) and chemotherapy, based on the findings of the CLEOPATRA trial (Baselga et al, 2012; Swain et al, 2015). Only 10% of patients in the CLEOPATRA trial received trastuzumab for EBC, but this pre-treated group is likely to represent a larger proportion of patients treated in routine clinical care. In our cohort 20% of patients starting trastuzumab for MBC had received trastuzumab for EBC. Given our treatment duration and survival estimates for trastuzumab pre-treated patients were shorter than those for trastuzumab-naive patients, it is possibile that trial estimates for patients receiving trastuzumab, pertuzumab and chemotherapy will overestimate the survival times for trastuzumab pre-treated patients. This is an important consideration for clinicians when estimating and explaining survival time to trastuzumab pre-treated patients, at least until more data are available on the outcomes of this subgroup of patients.

We observed 257 patients who initiated trastuzumab for MBC within 12 months of their last EBC trastuzumab dispensing. These patients have largely been excluded from clinical trials of trastuzumab for MBC. Not surprisingly, they have poorer survival outcomes relative to other trastuzumab pre-treated patients. These patients may be better served from newer HER2-targeted therapies such as trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) (Kadcyla, Genentech; Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd), which was evaluated in the EMILIA study (Verma et al, 2012) that included patients who relapsed with MBC within 6 months of completing trastuzumab for EBC.

Moreover, a retrospective sub-study of the HERA trial (Piccart-Gebhart et al, 2005) examined patients relapsing after completing one year of adjuvant trastuzumab who went on to receive trastuzumab for MBC (Metzger-Filho et al, 2016). The researchers stratified patients as we did and reported survival estimates similar to ours (median OS: 17.8 months for patients initiating metastatic therapy <12 months from the end of early stage treatment and 23.7 months for those initiating MBC treatment ⩾12 months from the end of EBC treatment).

Although resistance to trastuzumab is a potential contributor to the shorter survival outcomes in the trastuzumab pre-treated patients, another factor that should be considered is resistance to taxane chemotherapy. Of the 383 (60%) trastuzumab pre-treated patients who received concomitant taxanes for MBC in our study, 258 (67%) also received concomitant taxanes for EBC. During the time period of our study, taxanes were the recommended treatment partner for adjuvant trastuzumab and Herceptin Program prescribing restrictions were such that taxanes were the only chemotherapy oncologists could combine with trastuzumab as first-line treatment for MBC (Daniels et al, 2017). Patients previously treated with concomitant trastuzumab and taxane therapy for EBC may be more responsive to non-taxane based chemotherapy combined with trastuzumab at the time of relapse, or to one of the newer agents now available, such as pertuzumab or T-DM1. Although they did not report specific details around prior chemotherapy exposure for trastuzumab pre-treated patients, both the MARIANNE and CLEOPATRA trials reported longer median PFS estimates for trastuzumab pre-treated patients from the T-DM1 and pertuzumab arms, respectively, compared with the trastuzumab+taxane control arms (Baselga et al, 2012; Perez et al, 2017).

This study used linked population-based administrative data to undertake this real-world study. We have used national databases to identify what is, to our knowledge, the largest cohort of trastuzumab pre-treated patients in the literature to date. Use of these data has enabled precise estimates of survival from a generalisable sample, subgroup analyses and complete cohort follow-up due to Australia’s single-payer system. Although Australians may have accessed trastuzumab through other means, it is highly unlikely given the national subsidy system provided free access to this medicine.

Our study has a number of limitations inherent to using adminstrative data for observational research. First, the data used in this study were collected for reimbursement purposes and lack important clinical measures such as TNM staging, performance status, dates of diagnoses of EBC and MBC, dates of progression, adverse events and other baseline characteristics. As such, we used the available data to construct our subgroups and proxies for some clinical factors.There is potential for misclassification of our patient groups and our results should be considered with these limitations in mind. Hormone receptor status was ascertained from dispensing records for patients who had at least one year of observation time before initiation of trastuzumab for MBC (a baseline period) and may not have captured all HR-positive patients. Among trastuzumab-naive patients we are unable to determine if those receiving prior chemotherapy and endocrine therapy received these treatments for EBC or MBC. We are unable to identify patients who accessed (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab through other funding mechanisms, such as clinical trials or self funding, before it was subsidised in October 2006. Another limitation is that the data are largely based on patients starting treatment 5 to 10 years ago. In HER2+ MBC, numerous new and effective treatments have become available over the last 5 years; thus, the survival estimates in this study are likely to be conservative. In this era of emerging therapies the challenge for clinicians and policy makers is how best to use data from existing cohort studies and trials to provide estimates of survival time for patients starting treatment today. Finally, unlike randomised controlled trials, it is challenging to make direct comparisons between outcomes of patient subgroups due to their underlying differences at the time of treatment, particularly with limited clinical information, and thus we have not undertaken stastistical comparisons.

Conclusion

Our study provides valuable new information about the survival experience and duration of therapy for patients treated with trastuzumab for both EBC and MBC that can inform clinical practice, health service planning and the design of future trials for this important under-researched population. Recent clinical trials of HER2-targeted therapies in the metastatic setting have begun to include larger proportions of patients who received (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab (Harbeck et al, 2016; Perez et al, 2017). With ongoing advances in the management of HER2-positive breast cancer, the reporting of the outcomes for these patients from trials of HER2-targeted therapies and other anti-cancer medicines, complemented by evidence from population settings as undertaken in this work, will improve our understanding of the prognosis and treatment of this growing patient population.

Change history

06 February 2018

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Baselga J, Cortes J, Kim SB, Im SA, Hegg R, Im YH, Roman L, Pedrini JL, Pienkowski T, Knott A, Clark E, Benyunes MC, Ross G, Swain SM, Group CS (2012) Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 366 (2): 109–119.

Cardoso F, Costa A, Norton L, Cameron D, Cufer T, Fallowfield L, Francis P, Gligorov J, Kyriakides S, Lin N, Pagani O, Senkus E, Thomssen C, Aapro M, Bergh J, Di Leo A, El Saghir N, Ganz PA, Gelmon K, Goldhirsch A, Harbeck N, Houssami N, Hudis C, Kaufman B, Leadbeater M, Mayer M, Rodger A, Rugo H, Sacchini V, Sledge G, van't Veer L, Viale G, Krop I, Winer E (2012) 1st International consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 1). Breast 21 (3): 242–252.

Daniels B, Lord SJ, Kiely BE, Houssami N, Haywood P, Lu CY, Ward RL, Pearson S-A (2017) Use and outcomes of targeted therapies in early and metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer in Australia: protocol detailing observations in a whole of population cohort. BMJ Open 7: 1.

Gruschkus SK, Doan JF, Chen C, Forsyth MT, Lalla D, Shing M (2010) First-line patterns of care and outcomes of HER2-positive breast cancer patients who progressed after receiving adjuvant trastuzumab in the outpatient community setting. Journal of Clinical Oncology 28(15_suppl) 684–684.

Harbeck N, Huang CS, Hurvitz S, Yeh DC, Shao Z, Im SA, Jung KH, Shen K, Ro J, Jassem J, Zhang Q, Im YH, Wojtukiewicz M, Sun Q, Chen SC, Goeldner RG, Uttenreuther-Fischer M, Xu B, Piccart-Gebhart M, group LU-Bs (2016) Afatinib plus vinorelbine versus trastuzumab plus vinorelbine in patients with HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer who had progressed on one previous trastuzumab treatment (LUX-Breast 1): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 17 (3): 357–366.

Krell J, James CR, Shah D, Gojis O, Lim A, Riddle P, Ahmad R, Makris A, Cowdray A, Chow A, Babayev T, Madden P, Leonard R, Cleator S, Palmieri C (2011) Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer relapsing post-adjuvant trastuzumab: pattern of recurrence, treatment and outcome. Clin Breast Cancer 11 (3): 153–160.

Lambertini M, Ferreira AR, Poggio F, Puglisi F, Bernardo A, Montemurro F, Poletto E, Pozzi E, Rossi V, Risi E, Lai A, Zanardi E, Sini V, Ziliani S, Minuti G, Mura S, Grasso D, Fontana A, Del Mastro L (2015) Patterns of Care and Clinical Outcomes of First-Line Trastuzumab-Based Therapy in HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients Relapsing After (Neo)Adjuvant Trastuzumab: An Italian Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. Oncologist 20 (8): 880–889.

Lang I, Bell R, Feng FY, Lopez RI, Jassem J, Semiglazov V, Al-Sakaff N, Heinzmann D, Chang J (2014) Trastuzumab retreatment after relapse on adjuvant trastuzumab therapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: final results of the Retreatment after HErceptin Adjuvant trial. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 26 (2): 81–89.

Metzger-Filho O, de Azambuja E, Procter M, Krieguer M, Smith I, Baselga J, Cameron D, Untch M, Jackisch C, Bell R, Gianni L, Goldhirsch A, Piccart M, Gelber RD, Team HS (2016) Trastuzumab re-treatment following adjuvant trastuzumab and the importance of distant disease-free interval: the HERA trial experience. Breast Cancer Res Treat 155 (1): 127–132.

Murthy RK, Varma A, Mishra P, Hess KR, Young E, Murray JL, Koenig KH, Moulder SL, Melhem-Bertrandt A, Giordano SH, Booser D, Valero V, Hortobagyi GN, Esteva FJ (2014) Effect of adjuvant/neoadjuvant trastuzumab on clinical outcomes in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Cancer 120 (13): 1932–8.

Negri E, Zambelli A, Franchi M, Rossi M, Bonifazi M, Corrao G, Moja L, Zocchetti C, La Vecchia C (2014) Effectiveness of trastuzumab in first-line HER2+ metastatic breast cancer after failure in adjuvant setting: a controlled cohort study. Oncologist 19 (12): 1209–1215.

Perez EA, Barrios C, Eiermann W, Toi M, Im YH, Conte P, Martin M, Pienkowski T, Pivot X, Burris H 3rd, Petersen JA, Stanzel S, Strasak A, Patre M, Ellis P (2017) Trastuzumab Emtansine With or Without Pertuzumab Versus Trastuzumab Plus Taxane for Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive, Advanced Breast Cancer: Primary Results From the Phase III MARIANNE Study. J Clin Oncol 35 (2): 141–148.

Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, Goldhirsch A, Untch M, Smith I, Gianni L, Baselga J, Bell R, Jackisch C, Cameron D, Dowsett M, Barrios CH, Steger G, Huang CS, Andersson M, Inbar M, Lichinitser M, Lang I, Nitz U, Iwata H, Thomssen C, Lohrisch C, Suter TM, Ruschoff J, Suto T, Greatorex V, Ward C, Straehle C, McFadden E, Dolci MS, Gelber RD Herceptin Adjuvant Trial Study T (2005) Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 353 (16): 1659–1672.

Rier HN, Levin MD, van Rosmalen J, Bos M, Drooger JC, de Jong P, Portielje JEA, Elsten EMP, Ten Tije AJ, Sleijfer S, Jager A (2017) First-Line Palliative HER2-Targeted Therapy in HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Is Less Effective After Previous Adjuvant Trastuzumab-Based Therapy. Oncologist.

Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, Suman VJ, Geyer CE Jr., Davidson NE, Tan-Chiu E, Martino S, Paik S, Kaufman PA, Swain SM, Pisansky TM, Fehrenbacher L, Kutteh LA, Vogel VG, Visscher DW, Yothers G, Jenkins RB, Brown AM, Dakhil SR, Mamounas EP, Lingle WL, Klein PM, Ingle JN, Wolmark N (2005) Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 353 (16): 1673–1684.

Schemper M, Smith TL (1996) A note on quantifying follow-up in studies of failure time. Control Clin Trials 17 (4): 343–346.

Spano J-P, Vignot S, Ho XD, Zongo N, Magneux C, Genestie C, TdlM Rouge, Lefranc J-P, Khayat D, Gligorov J (2012) Outcome of HER2-positive breast cancer patients following metastatic relapse after adjuvant trastuzumab treatment since EMA regulatory approval. Journal of Clinical Oncology 30(15_suppl) 641–641.

Srasuebkul P, Dobbins TA Elements of Cancer Care I Pearson SA (2014) Validation of a proxy for estrogen receptor status in breast cancer patients using dispensing data. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 10 (2): e63–e68.

Swain SM, Baselga J, Kim SB, Ro J, Semiglazov V, Campone M, Ciruelos E, Ferrero JM, Schneeweiss A, Heeson S, Clark E, Ross G, Benyunes MC, Cortes J, Group CS (2015) Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 372 (8): 724–734.

Verma S, Miles D, Gianni L, Krop IE, Welslau M, Baselga J, Pegram M, Oh DY, Dieras V, Guardino E, Fang L, Lu MW, Olsen S, Blackwell K, Group ES (2012) Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 367 (19): 1783–1791.

Xu B, Hu X, Zheng H, Wang X, Zhang Q, Cui S, Liu D, Liao N, Luo R, Sun Q, Yu S (2016) Outcomes of re-treatment with first-line trastuzumab plus a taxane in HER2 positive metastatic breast cancer patients after (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab: A prospective multicenter study. Oncotarget 7 (31): 50643–50655.

Yardley DA, Kaufman PA, Brufsky A, Yood MU, Rugo H, Mayer M, Quah C, Yoo B, Tripathy D (2014) Treatment patterns and clinical outcomes for patients with de novo versus recurrent HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 145 (3): 725–734.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of Sally Crossing (AM) (1946–2016) as the Health Consumer Advocate on this research programme. We thank the Department of Human Services for providing the data for this research. This study was funded in part by a Cancer Australia Priority Driven Collaborative Support Scheme (ID: 1050648) and the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Medicines and Ageing (CREMA; ID: 1060407). BD is supported by an NHMRC Postgraduate Research Scholarship (ID: 1094325), the Sydney Catalyst Translational Cancer Research Centre and a CREMA PhD scholarship top-up. NH receives funding through a National Breast Cancer Foundation (Australia) Breast Cancer Research Leadership Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

BEK has received conference support and a speaker’s honorarium from Roche. RLW is a member of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) and SP is a member of the Drug Utilisation Sub Committee of the PBAC. The views expressed in this paper do not represent those of either committee. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Daniels, B., Kiely, B., Houssami, N. et al. Survival outcomes for Australian women receiving trastuzumab for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer following (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab: a national population-based observational study (2006–2014). Br J Cancer 118, 441–447 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.405

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.405