Abstract

A predominant mutation within the BRCA1 predisposition gene, 185delAG, has been detected in about 1 % of the Ashkenazi population, considered a high-risk group for breast and ovarian cancers. We examined 639 unrelated healthy Jews of Iraqi extraction, a presumed low-risk group, for the existence of this mutation. Three individuals were identified as 185delAG mutation carriers, and haplotype analysis of the Iraqi mutation carriers revealed that 2 of the Iraqis shared a common haplotype with 6 Ashkenazi mutation carriers, and 1 had a haplotype which differed by a single marker. This study suggests that the BRCA1 185delAG mutation also occurs in populations considered at low-risk for breast and ovarian cancers, and that it might have occurred prior to the dispersion of the Jewish people in the Diaspora, at least at the time of Christ.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The search for germline mutations within breast cancer susceptibility genes has focused, for the most part, on populations at risk for developing breast and ovarian cancer [1]. Several predominant mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 were reported in Ashkenazi Jews, and it is estimated that about 2% of the general Ashkenazi population carry either 185delAG BRCA1 or 6174delT BRCA2 mutations, perhaps contributing to the higher risk for breast cancer in this group [2–4]. Yet, only scarce information is available on the status of breast cancer susceptibility genes in low-risk populations, which might reflect bona fide low mutation rates or underreporting. Several cases of the 185delAG germline mutation in Jewish-Iraqi families with breast and ovarian cancer have already been reported [5, 6]. In our Oncogenetics Clinic, the same mutation has been detected in several other Jewish-Iraqi cancer-prone families, suggesting that it might be more than occasional in this group.

Cancer statistics in Israel indicate that Jews born in Europe or America (so-called Ashkenazim) are at a higher-risk for developing breast cancer than Asian- and African-born individuals (so-called non-Ashkenazim): in 1993 the rate of breast cancer per 100,000 in ‘Ashkenazi’ women was 89.8, compared with 70.7 for Asian-born and 55.6 for North-African-born Jewish women [7]. Throughout the history of the Jewish people in the Diaspora, which began around 70 AD, the Iraqi and Ashkenazi populations remained geographically and ethnically distinct. However, genetic analyses of several markers identify common origins for Ashkenazi, Iraqi, Iranian, and Libyan Jews suggesting a shared genetic prototype [8, 9].

Taken together, these facts, led us to hypothesize that 185delAG BRCA1 is yet another example of an ancient Jewish genetic prototype. With that purpose in mind, we examined 639 Jewish-Iraqi individuals for the presence of the 185delAG BRCA1 germline mutation, and for the allelic patterns of mutation carriers using intragenic BRCA1 markers.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Six hundred and thirty-nine Iraqi-born individuals (310 men and 329 women) with an age range of 32–93 years were anonymously tested for the 185delAG BRCA1 germline mutation. These individuals were previously identified and recruited at the Sheba Medical Center (SMC), without preselection for history of cancer. All were volunteers unrelated to each other, interviewed with respect to family history of cancer, and their Iraqi ancestry was verified at least two generations back. The original study was approved by the Human Subjects Ethics Committee of the SMC. In addition, 6 unrelated Ashkenazi women with breast or ovarian cancer, who were found to be carriers of the 185delAG mutation in the Oncogenetics Clinic at the SMC, were used as a reference and control for the allelic pattern of 17q markers (see below).

Genetic Analysis

PCR amplification of BRCA1 exon 2 from peripheral blood DNA, was performed as previously described [10–12]. Heteroduplex formation [11] was followed by a 50-volt, 15-hour electrophoresis at room temperature on MDE gels (Hydrolink, AT Biochem Malvern, Pa., USA) in 0.6 x TBE buffer and silver staining. DNA sequencing was performed for PCR fragments that consistently displayed abnormal migration patterns on heteroduplex analysis, with the use of a biotinylated primer [13]. Haplotype analysis used 3 markers intragenic to the BRCA1 gene: D17S855, D17S1322, D17S1323. PCR amplification, gel electrophoresis and autoradiography were performed using standard protocols [14, 15].

Statistical Analysis

Fisher’s exact test was applied to evaluate the significance of the occurrence rate of 185delAG in the Iraqi and the Ashkenazi populations. The age-standardized rate (ASR) used for computation was based on the world population [16].

Results

Detection of 185delAG Mutation

The 185delAG mutation was detected in 3 of 639 (0.47%) Iraqi Jews. Integrating previous data [17] and our own results, we noted that the 3 Iraqi mutation carriers, 2 females and 1 male, ages 69, 75 and 93, had no personal or family history of cancer. Additionally, one 185delAG mutation carrier was detected with the type II factor XI mutation, commonly found in Iraqis and Ashkenazim.

Haplotype Analysis of 185delAG Mutation Carriers

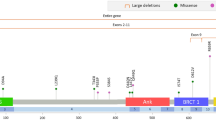

Analysis of allelic patterns using 3 intragenic BRCA1 markers was performed on the 3 Iraqi and 6 Ashkenazi-Jewish 185delAG mutation carriers. The designation of the ‘Ashkenazi allele’ as a mutation-bearing allele was based on similar analyses of family members (data not shown). Haplotype analysis revealed that 2 of the 3 Iraqi mutation carriers share a common BRCA1 Ashkenazi haplotype. For marker D17S1322, the alleles detected in individual 1290 were different from the allele 5 that is part of the BRCA1 4-5-3 haplotype (fig. 1). The common BRCA1 Ashkenazi haplotype was not detected in any noncarrier Iraqi individual, as assessed by analyzing 100 alleles.

Haplotype analysis of the 185delAG mutation carriers. The numbers at the top of each allele pair indicate patient numbers. The number on the far right, the markers used. The allele numbers are designated according to size, with the higher numbers representing larger alleles, a Iraqi carriers (n = 3). b Ashkenazi carriers (n = 6).

Statistical Analysis

The apparent rate of 185delAG mutation (3 of 639; 0.47%) in Iraqi-Jews is not statistically different from the reported rate in Ashkenazi mutation carriers (8/858; 0.9%) [2], (odds ratio = 2; 95% confidence interval 0.53-7.55; p = 0.37).

In 1993,1,166 breast cancer cases occurred in so-called Ashkenazi women and 262 Asian-born women, of whom 108 are Iraqi born. The difference between the ASR of breast cancer occurrence in Ashkenazi women per 100,000 (90.6) versus that of the Iraqi-born women (70.3) was of borderline significance (p = 0.065).

Discussion

This study suggests that the 185delAG BRCA1 germline mutation is present in the Iraqi Jewish population at rates similar to that of the Ashkenazi Jews. Yet, Askhena-zi and Iraqi Jews differ with respect to the rate of breast and ovarian cancers (p = 0.065). Thus, it seems that the 185delAG in the Ashkenazi and the Iraqi populations cannot solely be attributed to the ethnic diversity in the occurrence of breast cancer, and other factors — genetic or environmental — may account for that ethnic diversity in cancer rates. Notably, the rate of 185delAG in Iraqi Jews (0.0047) is higher than the total number of BRCA1 mutations in the Caucasian population estimated from epidemiological studies (0.0012).

The 185delAG mutation occurred in the 6 breast and ovarian cancer Ashkenazi patients on the background of an identical haplotype. Therefore, the common haplotype shared by Ashkenazi and 2 of 3 Iraqi 185delAG carriers is suggestive of a common founder chromosome. Previous estimates of the dating of 185delAG, tracing it to 1235 AD were based exclusively on Ashkenazi mutation carriers [15, 18]. Since there is no evidence for population mixing or large-scale migration between these two groups [8], it seems that 185delAG emerged prior to the dispersion of the Jews around 70 AD.

The additional haplotype identified in an Iraqi individual differs from the Ashkenazi haplotype only by a single intragenic marker, flanked by common alleles. The possibility of a double recombination event is statistically and genetically unlikely. Rather, this specific larger allele could have evolved from the original prototype via an expansion of a dinucleotide repeat. Indeed, such dynamics have elegantly been shown for other inherited disorders [19–21].

In conclusion, the 185delAG BRCA1 mutation occurs in Ashkenazi (high-risk) and Iraqi (low-risk) Jewish populations, on the background of a similar haplotype. We suggest that this specific mutation may be part of the ancient Jewish genetic pool and have an earlier genesis than presently estimated.

Note Added in Proof

A BRCA1 Mutation in an Iraqi individual was recently described (Breast Cancer Information Code-Accession Number 1491).

References

Szabo CI, King MC: Inherited breast and ovarian cancer. Hum Mol Genet 1995;4:1811–1817.

Streuwing JP, Abeliovitch D, Peretz T, Avishai N, Kaback MM, Collins FS, Brody LC: The carrier frequency of the BRCA 1 185delAG mutation is approximately 1 percent in Ashkenazi Jewish individiuals. Nat Genet 1995; 11:198–200.

Roa BB, Boyd AA, Volick K, Richards CS: Ashkenazi Jewish population frequencies for common mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Nat Genet 1996;14:185–187.

Odduoux C, Streuwing JP, Clayton CM, Neuhausen S, Brody LC, Kaback M, Haas B, Norton L, Borgen P, Jhanwar S, Goldgar D, Ostrer H, Offit K: The carrier frequency of the BRCA2 6174delT mutation among Ashkenazi Jewish individuals is approximately 1%. Nat Genet 1996;14:188–190.

Sher C, Sharabani-Gargir L, Shohat M: Breast cancer and BRCA1. N Engl J Med 1996;334: 1199.

Abeliovich D, Kaduri L, Lerer I, Weinberg N, Amir G, Sagi M, Zlotogora J, Heching N, Peretz T: The founder mutation 185delAG and 5382InsC in BRCA1 and 6174delT in BRCA2 appear in 60% of ovarian cancer and 30% of early onset breast cancer patients among Ashkenazi women. Am J Hum Genet 1997;60: 505–514.

Israel Cancer Registry: Cancer in Israel 1993: Facts and figures. Ministry of Health, Jerusalem, 1995.

Bonne-Tamir B, Asbel S, Bar-Shani S: Ethnic communities in Israel: The genetic blood markers of Babylonian Jews. Am J Phys Anthropol 1978;49:457–464.

Bonne-Tamir B, Zoosman-Disakin A, Ticher A: Genetic diversity among Jews reexamined: Preliminary analysis at the DNA level; in Bonne-Tamir B, Adam A (eds): Genetic Diversity among Jews. Diseases and Markers at the DNA Level. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1992, pp 80–94.

Friedman LS, Ostermeyer EA, Szabo CI, Dowd P, Lynch ED, Powell SE, King MC: Confirmation of BRCA 1 by analysis of germline mutations linked to breast and ovarian cancer in ten families. Nat Genet 1994;8:399–404.

Ozelik H, Antebi YJ, Cole DEC, Andrulis IL: Heteroduplex and protein truncation analysis of the BRCA1 185delAG mutation. Hum Genet 1996;98:310–312.

Modan B, Gak E, Hirsch G, Bar-Sade Bruchim R, Theodor L, Lubin F, Ben-Baruch G, Beller U, Fishman A, Dgani R, Menczer J, Papa MZ, Friedman E: High frequency of the 185delAG mutation in ovarian cancer in Israel. JAMA 1996;276:1823–1825.

Syvänen AC, Aalto-Setälä K, Kontula K, Sö-derlund H: Direct sequencing of affinity captured amplified human DNA: Application to the detection of apolipoprotein E polymorphism. FEBS Lett 1989;258:71–74.

Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harsman K, Tavtigian S, Liu Q, Cochran C, Bennet LM, Ding W, Bell R, Rosenthal J, Hussey C, Tran T, McClure M, Frye C, Hattier T, Pelps R, Haugen-Strano A, Katcher H, Ya-kumo K, Gholami Z, Shaffer D, Stone S, Bayer S, Wray C, Bogden R, Dayananth P, Ward J, Tonin P, Narod S, Bristow PK, Norris FH, Hel-vering L, Morrison P, Rosteck P, Lai M, Barrett JC, Lewis C, Neuhausen S, Cannon-Albright L, Goldgar D, Wessman R, Kamb A, Skolnick MH: A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science 1994;266:66–71.

Neuhausen SL, Mazoyer S, Friedman L, Strat-ton M, Offit K, Caligo A, Tomlinson G, Cannon-Albright L, Bishop T, Kelsell D, Solomon E, Weber B, Couch F, Streuwing J, Tonin P, Durcher F, Narod S, Skolnick MH, Lenoir G, Serova O, Ponder B, Stoppa-Lynnrd D, Easton D, King MC, Goldgar D: Haplotype and phe-notype analysis of six recurrent BRCA1 mutations in 61 families: Results of an international study. Am J Hum Genet 1996;58:271–280.

Cancer incidence in five continents. Lyon, IARC, 1987, vol 5.

Shpilberg O, Peretz H, Zivelin A, Yatuv R, Chetrit A, Kulka T, Stern C, Weiss E, Seligsohn U: One of the two common mutations causing factor XI deficiency in Ashkenazi Jews (type II) is also prevalent in Iraqi Jews, who represent the ancient gene pool of Jews. Blood 1995;85: 429–432.

Berman DB, Wagner-Costalas J, Schultz DC, Lynch DC, Daly M, Goodwin AK: Two distinct origins of a common mutation in breast-ovarian cancer families: A genetic study of 15 185delAG-mutation kindreds. Am J Hum Genet 1996;58:1166–1176.

Morral N, Bertranpetit J; Estivill X, Nunes V, Casals T, Gimenez J, Reis A, Varon Mateeva R, Macek M Jr, Kalaydjieva L: The origin of the major cystic fibrosis mutation (delta F508) in European populations. Nat Genet 1994;7: 169–175.

William A, Rubinstein DC: Microsatellites are subject to directional evolution. Nat Genet 1996;12:13–14.

Ellgern H, Saino N, Moller AP: Directional evolution in germline microsatellite mutations. Nat Genet 1996;13:391–393.

Acknowledgment

This work was performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree from the Sackler School of Medicine at the Tel-Aviv University for Revital Bruchim Bar-Sade. We would like to thank Dr. Moshe Frydman for constructive reading of the manuscript and insightful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bar-Sade, R.B., Theodor, L., Gak, E. et al. Could the 185 deIAG BRCA1 Mutation Be an Ancient Jewish Mutation?. Eur J Hum Genet 5, 413–416 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405951

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405951