Abstract

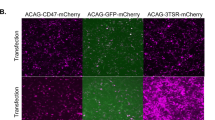

Tumor–endothelial interaction contributes to local prostate tumor growth and distant metastasis. In this communication, we designed a novel approach to target both cancer cells and their “crosstalk” with surrounding microvascular endothelium in an experimental hormone refractory human prostate cancer model. We evaluated the in vitro and in vivo synergistic and/or additive effects of a combination of conditional oncolytic adenovirus plus an adenoviral-mediated antiangiogenic therapy. In the in vitro study, we demonstrated that human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and human C4-2 androgen-independent (AI) prostate cancer cells, when infected with an antiangiogenic adenoviral (Ad)-Flk1-Fc vector secreting a soluble form of Flk1, showed dramatically inhibited proliferation, migration and tubular formation of HUVEC endothelial cells. C4-2 cells showed maximal growth inhibition when coinfected with Ad-Flk1-Fc and Ad-hOC-E1, a conditional replication-competent Ad vector with viral replication driven by a human osteocalcin (hOC) promoter targeting both prostate cancer epithelial and stromal cells. Using a three-dimensional (3D) coculture model, we found that targeting C4-2 cells with Ad-hOC-E1 markedly decreased tubular formation in HUVEC, as visualized by confocal microscopy. In a subcutaneous C4-2 tumor xenograft model, tumor volume was decreased by 40–60% in animals treated with Ad-Flk1-Fc or Ad-hOC-E1 plus vitamin D3 alone and by 90% in a combined treatment group, compared to untreated animals in an 8-week treatment period. Moreover, three of 10 (30%) pre-established tumors completely regressed when animals received combination therapy. Cotargeting tumor and tumor endothelium could be a promising gene therapy strategy for the treatment of both localized and metastatic human prostate cancer.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA . Cancer statistics, 1999. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:8–31.

Koeneman KS, Yeung F, Chung LW . Osteomimetic properties of prostate cancer cells: a hypothesis supporting the predilection of prostate cancer metastasis and growth in the bone environment. Prostate. 1999;39:246–261.

Jacobs SC . Spread of prostatic cancer to bone. Urology. 1983;21:337–344.

Pollen JJ, Gerber K, Ashburn WL, Schmidt JD . Nuclear bone imaging in metastatic cancer of the prostate. Cancer. 1981;47:2585–2594.

Tu SM, Millikan RE, Mengistu B, et al. Bone-targeted therapy for advanced androgen-independent carcinoma of the prostate: a randomised phase II trial. Lancet. 2001;357:336–341.

Sung SY, Chung LW . Prostate tumor-stroma interaction: molecular mechanisms and opportunities for therapeutic targeting. Differentiation. 2002;70:506–521.

Hsieh CL, Gardner TA, Miao L, Balian G, Chung LW . Cotargeting tumor and stroma in a novel chimeric tumor model involving the growth of both human prostate cancer and bone stromal cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11:148–155.

Matsubara S, Wada Y, Gardner TA, et al. A conditional replication-competent adenoviral vector, Ad-OC-E1a, to cotarget prostate cancer and bone stroma in an experimental model of androgen-independent prostate cancer bone metastasis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6012–6019.

Folkman J . What is the evidence that tumors are angiogenesis dependent? J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:4–6.

Arap W, Pasqualini R, Ruoslahti E . Cancer treatment by targeted drug delivery to tumor vasculature in a mouse model. Science. 1998;279:377–380.

Cao R, Wu HL, Veitonmaki N, et al. Suppression of angiogenesis and tumor growth by the inhibitor K1-5 generated by plasmin-mediated proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5728–5733.

Sacco MG, Cato EM, Ceruti R, et al. Systemic gene therapy with anti-angiogenic factors inhibits spontaneous breast tumor growth and metastasis in MMTVneu transgenic mice. Gene Therapy. 2001;8:67–70.

Folkman J . Angiogenesis and angiogenesis inhibition: an overview. Exs. 1997;79:1–8.

Fidler IJ, Ellis LM . The implications of angiogenesis for the biology and therapy of cancer metastasis. Cell. 1994;79:185–188.

Ranieri G, Gasparini G . Angiogenesis and angiogenesis inhibitors: a new potential anticancer therapeutic strategy. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2001;1:241–253.

Niethammer AG, Xiang R, Becker JC, et al. A DNA vaccine against VEGF receptor 2 prevents effective angiogenesis and inhibits tumor growth. Nat Med. 2002;8:1369–1375.

Li L, Wartchow CA, Danthi SN, et al. A novel antiangiogenesis therapy using an integrin antagonist or anti-Flk-1 antibody coated 90Y-labeled nanoparticles. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:1215–1227.

Lin P, Sankar S, Shan S, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth by targeting tumor endothelium using a soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor. Cell Growth Differ. 1998;9:49–58.

Shepherd FA . Angiogenesis inhibitors in the treatment of lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2001;34(Suppl 3):S81–S89.

Wu HC, Hsieh JT, Gleave ME, Brown NM, Pathak S, Chung LW . Derivation of androgen-independent human LNCaP prostatic cancer cell sublines: role of bone stromal cells. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:406–412.

Kuo CJ, Farnebo F, Yu EY, et al. Comparative evaluation of the antitumor activity of antiangiogenic proteins delivered by gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4605–4610.

Hsieh CL, Yang L, Miao L, et al. A novel targeting modality to enhance adenoviral replication by vitamin D(3) in androgen-independent human prostate cancer cells and tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3084–3092.

Graham FL, Prevec L . Methods for construction of adenovirus vectors. Mol Biotechnol. 1995;3:207–220.

Schmitz V, Wang L, Barajas M, Peng D, Prieto J, Qian C . A novel strategy for the generation of angiostatic kringle regions from a precursor derived from plasminogen. Gene Therapy. 2002;9:1600–1606.

Schleef RR, Birdwell CR . The effect of fibrin on endothelial cell migration in vitro. Tissue Cell. 1982;14:629–636.

Carson SD, Hobbs JT, Tracy SM, Chapman NM . Expression of the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells: regulation in response to cell density. J Virol. 1999;73:7077–7079.

Jackson MW, Roberts JS, Heckford SE, et al. A potential autocrine role for vascular endothelial growth factor in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:854–859.

Bostwick DG, Iczkowski KA . Microvessel density in prostate cancer: prognostic and therapeutic utility. Semin Urol Oncol. 1998;16:118–123.

Jones A, Fujiyama C . Angiogenesis in urological malignancy: prognostic indicator and therapeutic target. Br J Urol Int. 1999;83:535–555 quiz 555-536.

Lissbrant IF, Lissbrant E, Damber JE, Bergh A . Blood vessels are regulators of growth, diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets in prostate cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2001;35:437–452.

Yu JL, Rak JW, Coomber BL, Hicklin DJ, Kerbel RS . Effect of p53 status on tumor response to antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2002;295:1526–1528.

Retter AS, Figg WD, Dahut WL . The combination of antiangiogenic and cytotoxic agents in the treatment of prostate cancer. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2003;2:153–159.

Becker CM, Farnebo FA, Iordanescu I, et al. Gene therapy of prostate cancer with the soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor Flk1. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:548–553.

Rak J, Filmus J, Kerbel RS . Reciprocal paracrine interactions between tumour cells and endothelial cells: the ‘angiogenesis progression’ hypothesis. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:2438–2450.

Getzenberg RH, Light BW, Lapco PE, et al. Vitamin D inhibition of prostate adenocarcinoma growth and metastasis in the Dunning rat prostate model system. Urology. 1997;50:999–1006.

Majewski S, Szmurlo A, Marczak M, Jablonska S, Bollag W . Inhibition of tumor cell-induced angiogenesis by retinoids, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and their combination. Cancer Lett. 1993;75:35–39.

Fujioka T, Hasegawa M, Ishikura K, Matsushita Y, Sato M, Tanji S . Inhibition of tumor growth and angiogenesis by vitamin D3 agents in murine renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1998;160:247–251.

Shokravi MT, Marcus DM, Alroy J, Egan K, Saornil MA, Albert DM . Vitamin D inhibits angiogenesis in transgenic murine retinoblastoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:83–87.

Tseng JF, Farnebo FA, Kisker O, et al. Adenovirus-mediated delivery of a soluble form of the VEGF receptor Flk1 delays the growth of murine and human pancreatic adenocarcinoma in mice. Surgery. 2002;132:857–865.

Han JS, Qian D, Wicha MS, Clarke MF . A method of limited replication for the efficient in vivo delivery of adenovirus to cancer cells. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:1209–1216.

Haviv YS, Takayama K, Glasgow JN, et al. A model system for the design of armed replicating adenoviruses using p53 as a candidate transgene. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:321–328.

Chen CT, Lin J, Li Q, et al. Antiangiogenic gene therapy for cancer via systemic administration of adenoviral vectors expressing secretable endostatin. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:1983–1996.

Mahasreshti PJ, Kataram M, Wang MH, et al. Intravenous delivery of adenovirus-mediated soluble FLT-1 results in liver toxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2701–2710.

Kesterson RA, Stanley L, DeMayo F, Finegold M, Pike JW . The human osteocalcin promoter directs bone-specific vitamin D-regulatable gene expression in transgenic mice. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:462–467.

Clemens TL, Tang H, Maeda S, et al. Analysis of osteocalcin expression in transgenic mice reveals a species difference in vitamin D regulation of mouse and human osteocalcin genes. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1570–1576.

Kubo H, Gardner TA, Wada Y, et al. Phase I dose escalation clinical trial of adenovirus vector carrying osteocalcin promoter-driven herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase in localized and metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:227–241.

Hisatake J, Kubota T, Hisatake Y, Uskokovic M, Tomoyasu S, Koeffler HP . 5,6-trans-16-ene-vitamin D3: a new class of potent inhibitors of proliferation of prostate, breast, and myeloid leukemic cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4023–4029.

Maniotis AJ, Folberg R, Hess A, et al. Vascular channel formation by human melanoma cells in vivo and in vitro: vasculogenic mimicry. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:739–752.

Hendrix MJ, Seftor EA, Kirschmann DA, Seftor RE . Molecular biology of breast cancer metastasis. Molecular expression of vascular markers by aggressive breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:417–422.

Sharma N, Seftor RE, Seftor EA, et al. Prostatic tumor cell plasticity involves cooperative interactions of distinct phenotypic subpopulations: role in vasculogenic mimicry. Prostate. 2002;50:189–201.

Sood AK, Fletcher MS, Hendrix MJ . The embryonic-like properties of aggressive human tumor cells. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2002;9:2–9.

Breast Cancer Progression Working Party. Evidence for novel non-angiogenic pathway in breast-cancer metastasis. Lancet. 2000;355:1787–1788.

Chang YS, di Tomaso E, McDonald DM, Jones R, Jain RK, Munn LL . Mosaic blood vessels in tumors: frequency of cancer cells in contact with flowing blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14608–14613.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mr Gary Mawyer for editorial assistance. This work was supported in part by DOD Grant DAMD17-03-1-0160 to C-LH, NIH 1 R01 CA95654-01 to CJK, DAMD17-00-1-0526 and NIH 1PO1CA098912-01 to LWKC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, F., Xie, Z., Kuo, C. et al. Cotargeting tumor and tumor endothelium effectively inhibits the growth of human prostate cancer in adenovirus-mediated antiangiogenesis and oncolysis combination therapy. Cancer Gene Ther 12, 257–267 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cgt.7700790

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cgt.7700790

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Oncolytic virotherapy for urological cancers

Nature Reviews Urology (2016)

-

Analysis of adenovirus trans-complementation-mediated gene expression controlled by melanoma-specific TETP promoter in vitro

Virology Journal (2010)

-

Current Issues and Future Directions of Oncolytic Adenoviruses

Molecular Therapy (2010)

-

Advances in Preclinical Investigation of Prostate Cancer Gene Therapy

Molecular Therapy (2007)

-

Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of IL-12, but not GM-CSF, expressing oncolytic herpes simplex virus for transgenic mouse derived prostate cancers

Cancer Gene Therapy (2006)