Abstract

Aim

To describe a novel technique, true endothelial cell (Tencell) transplant, for the transfer of donor endothelial cells with only a Descemet's carrier in patients with endothelial cell failure.

Method

Three patients treated for endothelial cell failure underwent Tencell transplantation. Two were performed to alleviate pain from bullous keratopathy, and one was performed to improve vision. Preoperative pain, vision, and corneal thickness were recorded and compared to the same parameters postoperatively.

Results

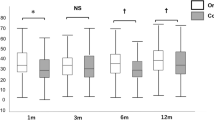

At 3 months postoperatively, all patients were pain free. The visual acuity had improved in all cases, and all three cases demonstrated a reduction of central corneal thickness. In two cases it was possible to perform an endothelial cell count.

Conclusion

This is the first description of Tencell transplantation in living subjects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endothelial cell failure is one of the most common reasons for penetrating keratoplasty (PK). However, the architectural disruption caused by PK can induce high degrees of both regular and irregular astigmatism and is often associated with a prolonged postoperative recovery.

Recent developments in deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK) lessen corneal disruption, so reducing induced astigmatism and enabling a more rapid visual recovery.1, 2, 3

However, the technique of DLEK is technically demanding. Additionally, it involves creating a stroma-to-stroma interface, which can reduce the final best-corrected visual acuity.

Transplantation of Descemet's membrane carrying viable endothelium has been described in human cadaver eyes.4 This has not, as yet, become a popular technique, perhaps owing to difficulties in harvesting the donor endothelial layer and its application to the host inner corneal surface without viable endothelial cell loss.

A technique that achieves the transfer of a disc of donor endothelial cells with only a Descemet's carrier, onto the posterior surface of the cornea, quickly and effectively via an 8.00 mm corneal incision is described.

Materials and methods

Three cases are described. All had endothelial cell failure and all underwent Tencell transplant. Fully informed consent was obtained for all patients prior to surgery. All patients were made aware that there were several surgical options available to treat their condition. They were all aware that this technique was new and unproven.

Both pre- and postoperative Snellen visual acuity, central corneal thickness, and endothelial cell counts were measured. Central corneal thickness was measured from an average of three consecutive recordings using an ultrasound pachymeter (Quantel Pocket). Endothelial cell counts were measured, where possible, using a Topcon SP100 cell counter. A single reading was taken from the central cornea.

Surgical technique

The technique uses a specifically designed instrument (Altomed) (Figure 1a), which is a cannula that ends in a flat platform at its distal end to support the endothelial cell layer. The platform facilitates transfer of the disc of Descemet's membrane and endothelium into the anterior chamber. The lumen of the cannula opens in the centre of this platform and is attached to a 2.5 ml syringe at its proximal end. Injection of air floats the donor disc up to adhere to host corneal stroma.

(a) Tappin's endothelial cannula with central port, through which air is injected to elevate the endothelial cell layer to position. (b) Preoperative appearance of case 3, demonstrating an oedematous cornea with marked guttata. (c) Postoperative appearance at 3 months, of case 3, with clear central cornea and peripheral oedema. (d) The interface between donor and recipient endothelium. Clear central cornea contrasts with thicker oedematous peripheral cornea.

Preparation of the recipient

Preparation of the recipient was performed before donor preparation to prevent undesired drying or damage to the endothelial cell layer.

The affected eye was dilated with guttae tropicamide 1% (Chauvin). An 8.0 mm partial thickness superior corneal or limbal incision was made using a 15° blade (Alcon Surgical), of approximately 2/3 corneal depth, similar to that for an extracapsular cataract extraction. A 27-G needle was bent at the tip by 30° so that it could be introduced into the anterior chamber, with the point bent upwards to perform the descemetorhexis.5 A 27-G needle was used, as it created its own self-sealing entry port in the peripheral cornea. The anterior chamber could therefore be maintained without the use of an anterior chamber maintainer or viscoelastic. Viscoelastic was not used to avoid the risk of any residual coating impairing adhesion of the endothelial cell layer. The visualisation of the descemetorhexis was facilitated using the red reflex. A central area of Descemet's membrane, approximately 7.5 mm in diameter, was removed. The operculum of Descemet's membrane was then aspirated via the paracentesis using a Simco cannula. There was no other preparation of the recipient cornea such as roughening of the stroma or stab incisions to permit fluid release. The anterior chamber was left formed with balanced salt solution (BSS Alcon laboratories).

Preparation of the donor material

The donor sclerocorneal button was placed epithelial side down on a silicone block corneal holder (Altomed). A shallow trephination of the endothelial surface was performed using a 7.5 mm long-handled trephine (Altomed). The edge of the circular disc of Descemet's membrane was held with two plane-tipped micro-forceps. This was gently peeled from the stroma and placed endothelial side down on a pre-prepared cannula, which had a layer of hydroxymethylcellulose on its carrier surface to protect the endothelial cells, and was mounted on a 2.5 ml syringe filled with air.

The partial thickness incision in the host eye was then made full thickness, thus creating a two-step corneal incision. The donor disc was introduced into the anterior chamber using Tappin's cannula. Once in the anterior chamber, the spatula was elevated and air was injected from the syringe through the centre of the cannula, which separated the donor disc from the spatula and apposed the endothelial disc to the bare stroma. The spatula was then removed and the anterior chamber was filled completely with air. The 8.0 mm section was sutured with five 10/0 nylon sutures. The anterior chamber was completely filled with air and left for approximately 5 min. The air bubble was then reduced to a mobile bubble, half the diameter of the cornea. The patient was positioned in a supine position for half an hour postoperatively.

Subconjunctival injections of cefuroxime 125 mg and betnesol 4 mg were administered at the end of the procedure. Postoperative guttae chloramphenicol and guttae dexamethasone 0.1% were used four times a day for the first week. Guttae dexamethasone was then continued four times a day for the next 6 months, in a regimen similar to that following a PK.

Case 1

An 86-year-old female had undergone left extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE) complicated by vitreous loss in 1989 and had a sutured posterior chamber lens in 2003. Postoperative visual acuity had been 6/18 with a refraction of +1.50/−7.00 at 96°, but the patient had subsequently developed age-related macular degeneration and then bullous keratopathy. The vision dropped to counting fingers at 1 m and the cornea was oedematous and thickened (pachymetry: 670 μm). There was no inflammation and the intraocular pressure was normal. The cornea was too oedematous to permit a preoperative endothelial cell count.

Case 2

A 68-year-old man with Fuchs endothelial dystrophy had undergone routine small-incision cataract extraction with foldable intraocular lens implantation. Unfortunately, his vision did not improve to an acceptable level. In the early postoperative period, the visual recovery was impeded by the development of cystoid macula oedema (CMO). Visual rehabilitation was complicated by corneal oedema but no bullous keratopathy, and this was still present at 6 months. There was considerable glare and best-corrected visual acuity was 6/12. The cornea was too oedematous to permit a preoperative endothelial cell count. The central corneal thickness was 647 μm, with obvious guttata (Figure 1b).

The patient agreed to undergo a Tencell transplant. Unfortunately, during the procedure, the donor endothelium tore and the procedure was abandoned. It was repeated 2 weeks later and proceeded uneventfully.

Case 3

A 65-year-old Indian lady presented with a painful left eye. The vision was perception of light. She had corneal decompensation with bullous keratopathy and a central corneal thickness of 593 μm. There was also a pupillary membrane, which prevented any view of the fundus. Initially she was given a bandage contact lens to alleviate the pain, but she was keen for an attempt to improve vision further. She underwent a combined procedure involving removal of the pupillary membrane, extracapsular cataract extraction with lens implantation, and endothelial cell transplant.

Results

Case 1

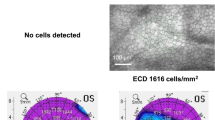

At 1 month postoperatively, there was a central area of clear cornea and the vision had improved from CF to 6/36. The vision remained 6/36 at the 3-month review; however, peripheral corneal epithelial oedema remained. The central endothelial cell count was 377 cells per mm2.

Case 2

Postoperative recovery was initially unremarkable. At 1 week, the vision was 6/36 and he felt the vision was improving. Unfortunately, 4 weeks after the Tencell transplant, CMO developed and the vision failed to improve further. Treatment was with guttae ketorolac trometamol three times a day, dexamethasone 0.1% four times a day, and an orbital floor injection of aqueous methylprednisolone acetate 40 mg. The CMO resolved. At 3 months after the Tencell transplant, visual acuity was 6/9. The central cornea was clear (Figure 1c) and the endothelial cell count was 1100 cells/mm2. There was clear demarcation between the central corneal region, which was clear and markedly thinner, and the peripheral, thicker, cornea. At the level of the endothelium there was a rolled edge where the donor endothelium came into contact with the loose edge of the recipient endothelium (Figure 1d, Table 1).

Case 3

At 2 months postoperatively, visual acuity had improved from PL to 6/60. The cornea was clearer with no bullae, and she was pain free. Scarring of the cornea limited further visual improvement. At the 3-month review the vision remained 6/60. The pachymetry measurements of the central cornea were not very thick preoperatively despite the presence of bullous keratopathy, and reflected either corneal scarring or an unusually thin cornea.

Discussion

This novel technique describes the use of a purpose-made cannula to transfer an endothelial disc to bare host corneal stroma, elevated to position, without wrinkles, using an injected air bubble.

The first and third cases had a guarded visual prognosis and were performed to relieve bullous keratopathy. The endothelial cell transplant in these cases was considered to be successful, as indicated by the lack of epithelial oedema and lack of pain. All three cases had thinner pachymetry postoperatively, indicating the successful transplantation of viable endothelial cells. The first case had a very low endothelial cell count postoperatively. Despite this, the central cornea was clear and a cell count could be recorded, which had not been possible preoperatively on account of gross corneal oedema. However, the high cell loss indicates a need to improve the harvesting or transfer techniques in order to reduce traumatic endothelial cell loss.

The second case encountered several problems. Firstly, a torn endothelial layer, which meant that the procedure had to be repeated 2 weeks later. It does, however, demonstrate that the procedure can be attempted on more than one occasion, a few weeks apart, with a successful result. It may have been advantageous to have prepared the donor material before the recipient to prevent this complication. Secondly, the patient developed CMO, a month after the Tencell transplant. The diagnosis was made clinically and was evidence of a clearing cornea. The CMO settled on treatment. It remains to be seen whether the incidence of CMO is higher with this technique. However, this patient developed CMO after his initial cataract extraction and it is unlikely that CMO is specifically associated with this technique.

Tencell transplantation is a quick and potentially simple method to treat endothelial cell failure. Like DLEK, it provides a rapid visual recovery from corneal decompensation, a condition that has traditionally been managed by PK. Architectural disruption of the cornea has limited the success of PK owing to high degrees of induced regular and irregular astigmatism, ametropia, prolonged healing, and fluctuating refractive results. The development of DLEK has demonstrated the ability to transplant endothelium and preserve the surface architecture of the cornea, enabling a more rapid recovery with a more stable and predictable postoperative refraction. DLEK involves a posterior lamellar dissection of both donor and recipient corneal stroma. The failed host endothelium and posterior stroma are then replaced with a button of donor endothelium on a thin lamella of donor stroma. Tencell transplantation avoids the manual lamellar dissection of both the donor and recipient stroma and the complications of converting to PK6 if there is inadvertent perforation of the recipient cornea during dissection. Our personal experience with DLEK is that there can be problems with adhesion of the donor button to the recipient stroma. Selective endothelial cell replacement with only a Descemet's membrane carrier may potentially be a way of avoiding this problem.

The low postoperative endothelial cell counts are probably because of trauma during the harvesting and transfer process. This needs improvement to match the excellent cell counts from DLEK.6 A larger series is needed to assess the long-term survival of the endothelial cells and the long-term visual outcomes using this method.

References

Melles GRJ, Lander F, van Dooren BTH, Pels E, Houdijn Beekhuis W . Preliminary clinical results of posterior lamellar keratoplasty through a sclerocorneal pocket incision. Ophthalmology 2000; 107: 1850–1857.

Terry MA . A new approach for endothelial transplantation; deep lamellar endothalial keratoplasty. Int Ophthal Clin 2003; 43(3): 183–193.

Melles GRJ, Lander F, Nieuwendaal C . Sutureless, posterior lamellar keratoplasty. Cornea 2002; 21(3): 325–327.

Melles GRJ, Lander F, Rietveld F . Transplantation of Descemet's membrane carrying viable endothelium through a small scleral incision. Cornea 2002; 21(4): 415–418.

Melles GRJ, Wijdh RHJ, Nieuwendaal MD . A technique to excise the descemet membrane from a recipient cornea (Descemetorhexis). Cornea 2004; 23(3): 286–288.

Ousley PJ, Terry MA . Stability of vision, topography, and cell density from 1 year to 2 years after deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty surgery. Ophthalmology 2005; 112: 50–57.

Acknowledgements

I thank my wife for her help in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Conflict of interest: none

No grants received

No proprietary interest

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tappin, M. A method for true endothelial cell (Tencell) transplantation using a custom-made cannula for the treatment of endothelial cell failure. Eye 21, 775–779 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702326

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702326

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Outcomes after Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty over a period of 7 years at a tertiary referral center: endothelial cell density, central corneal thickness, and visual acuity

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2021)

-

Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) early stage graft failure in eyes with preexisting glaucoma

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2017)