Abstract

Aims To evaluate the demographic profile, management and functional outcomes of patients with keratoconus attending the contact lens clinic of a tertiary ophthalmic referral centre over a one year period.

Methods A retrospective cohort analysis was conducted by reviewing the computerised hospital records of 130 patients attending The Western Eye Hospital contact lens department over the period 1st Jan 1999 to 31st Dec 1999. Data on age, gender, referral pattern, visual acuity, contact lens fitting, degree of visual success, and some information on penetrating keratoplasty were obtained.

Results 16.4% of all patients attending the Contact Lens clinic had keratoconus. The mean age at referral was 28.6 years and the mean age of keratoconus during the study period was 34.9 years. There was a predominance of male patients. Optometrists formed 72.2% of the referrals, and had prescribed some form of refractive correction in 70% of patients (two-thirds contact lenses) prior to hospital assessment. Of the 130 patients seen in the department during the study period, the post-referral management included bilateral contact lens fitting for 102 patients (78.5%), monocular contact lens fitting for 24 patients (18.5%) and no intervention in four patients (3%). The types of contact lenses used included PMMA lenses (2.7%), rigid gas permeable lenses (96.1%) of the spherical, elliptical and special cone lens designs, Keratosoft or Softperm lenses (0.8%) and scleral lenses (0.4%). Eleven eyes of eight patients had received penetrating keratoplasty (PK) prior to hospital assessment, of whom seven eyes needed post-surgical contact lens fitting. The main reasons for PK were contact lens intolerance (83%), frequent contact lens displacement (8.5%) and unsatisfactory visual acuity despite good contact lens fit (8.5%). Sixty-five per cent of patients were able to wear their contact lenses for more than 12 hours a day. With contact lens wear, 87% of patients had a visual acuity of 6/9 or better and 59% of eyes had improved visual acuity of 0.6 logMAR or more.

Conclusion Optometrists were the main source of referral for keratoconus patients to the Hospital Eye Service (HES).The mean age at referral was 28.6 years, with a predominance of male patients. Blurred vision formed the main presenting visual symptom on initial hospital assessment; subsequently, more than two-thirds of patients required bilateral contact lenses. Rigid gas permeable contact lenses remain the mainstay treatment for advanced keratoconus, with various designs enabling a large proportion of patients to attain improved visual acuity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Keratoconus is a bilateral, asymmetric, chronic, progressive ectasia of the cornea characterized by steepening and distortion of the cornea, thinning of the apical cornea, and sometimes, corneal scarring. Patients experience distorted vision that is usually treated with rigid contact lenses when spectacles no longer provide adequate vision. Corneal transplantation is the best and most successful surgical option for keratoconus when management with contact lenses fail.1 Although contact lenses form the mainstay of therapy in keratoconus,2 fitting contact lenses in keratoconus is a complex task. The challenge is to keep the patient contact lens-tolerant with good visual acuity in a cornea that may be changing in shape over time. In the UK, long term supply of contact lenses for keratoconic patients is provided by the National Health Service. Management of keratoconus at our institution includes an active contact lens department using various lens material and designs and which largely serves a referral population. This paper evaluates the demographic profile, hospital based contact lens management and functional outcomes of keratoconic patients within a tertiary ophthalmic referral centre.

Patients and methods

In a retrospective study, all patients who were diagnosed with keratoconus and who attended The Western Eye Hospital Contact Lens Department between 1st January 1999 and 31st December 1999 (12 months period) were identified using the computerised hospital record system. The following data were collected: age at the time of first referral, age at the time of the study, gender, route of referral into hospital, type of visual correction used before hospital consultation, visual symptoms at initial hospital presentation, type of contact lens prescribed after initial hospital referral and the degree of visual success in terms of best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) achieved. Further information on patients who underwent penetrating keratoplasty was also analysed.

Results

Seven hundred and eighty-six patients were seen in the Contact Lens Clinic during the study period; of these, 130 patients (16.4%) had keratoconus, 224 patients (28.7%) had high myopia, 252 patients (32%) had aphakia and 180 patients (22.9%) had other indications that required medical contact lens fitting (Table 1). The study included new referrals as well as follow-up patients within a one year period.

Of the 130 patients with keratoconus, we looked at the following demographic characteristics (see Table 2):

Age and gender

The mean age of the patients at the time of the study was 34.9 years (ranging from 16 to 69 years). The mean age of the patient at first referral to the hospital contact lens department was 28.6 years (ranging from 16 to 49 years). Eighty patients were male and 50 were female.

Method of referral and pre-referral refractive correction

Hospital referrals were initiated mainly by optometrists, usually in combination with a routine General Practitioners’ letter. This mode of referral accounted for 94 patients (72.2%). Of the rest, 31 patients (23.9%) were referred by Ophthalmologists and for five patients (3.9%) the source of referral was not identified. At first referral, 91 patients (70%) had used a refractive correction, of whom 31 patients wore glasses and 60 patients wore contact lenses.

Presenting visual symptoms

The visual problems experienced by the patients at initial referral are shown in Table 3. The most common complaint was blurred or distorted vision (78%), followed by poor visual acuity with spectacles (63%), sensitivity to light (27%) and frequent refractive changes (16%).

Outcome of hospital treatment

After initial hospital referral, some patients did not require a change of their existing contact lens whilst some others required either a change of their contact lenses or were fitted with contact lenses in the hospital, when they were not previously given any by their optician. The final outcome of the 130 patients with keratoconus who attended the Contact Lens clinic was: 102 patients (78.5%) were wearing contact lenses in both eyes, 24 patients (18.5%) were wearing contact lenses in one eye and four patients (3%) did not have contact lens in either eye (Table 4). The contact lenses were either fitted by their optometrists or by the hospital contact lens department after hospital referral. Patients with monocular fitting and patients without any contact lens in either eye were subjectively satisfied with the level of vision in their other eye or in both eyes respectively.

Eight of the 130 (6%) patients had received penetrating keratoplasty (PK) by the time they were seen at initial hospital visit. Of those eight patients, 11 eyes had PK. The main reasons for patients undergoing PK were contact lens discomfort (83%), unstable contact lens fit (8.5%) and poor visual acuity with contact lenses (8.5%). Seven out of 11 grafted eyes required contact lenses; in the other four eyes, no contact lens wear was indicated as patients were subjectively satisfied with their level of vision.

Fifty-seven per cent of patients had been successfully refitted with contact lenses since attending the hospital contact lens clinic due to initial problems relating to unsatisfactory vision, discomfort or unstable lens fit.

Types of contact lens worn

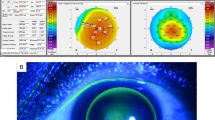

One hundred and twenty-six patients in total were presently wearing contact lenses in one or both eyes (102 binocular, 24 monocular), giving a total of 228 eyes with contact lenses. These included the seven eyes post-PK. Two hundred and nineteen eyes (96.1%) were fitted with rigid gas permeable contact lenses that included spherical, elliptical and cone lens design. Six eyes (2.7%) were fitted with PMMA lenses as previous attempts to change to a gas permeable material had been unsuccessful. Two eyes (0.8%) were fitted with keratoconus soft lenses and only one eye (0.4%) was fitted with a scleral lens (Figure 1).

Contact lens wearing schedule and visual acuity

Sixty-five per cent of patients wore their contact lenses for more than 12 hours a day, 31% of patients wore their contact lenses between 8 and 12 hours a day and 4% of patients wore their contact lenses for less than 8 hours a day. The mean number of years of successful contact lens wear was 14.5 years (ranging from 0.3 to 35 years).

Eighty-seven per cent of patients with keratoconus had a visual acuity of 6/9 or better with contact lenses. The improvement in visual acuity with contact lenses is shown in Figures 2 and 3. In 62 out of 116 (53.4%) right eyes, and in 72 out of 112 (64.2%) left eyes, the visual acuity improved by 0.6 logMAR or more. All Snellen visual acuities of patients were converted into logMAR figures which provide a finer resolution of the acuity scale for lower visual acuities.

Discussion

The basic epidemiology of keratoconus has been variably reported. The overall prevalence rate has been reported to be as low as 2 in 1000003 and as high as 1 in 285.4 Several factors make it difficult to evaluate the incidence and prevalence of keratoconus. The disease is of a gradual onset and variable severity; hence patients may not seek medical care for a long time despite having the condition if the disease is subtle. Studies based on medical records tend to underestimate the frequency of the disease. In our study, 16.4% of all patients attending the contact lens department during a 12-month period had keratoconus. Although The Western Eye Hospital is the main ophthalmic tertiary referral centre in West London, this figure is not indicative of the frequency of keratoconus in West London as some patients with mild keratoconus might have been discovered and followed up by optometrists without being referred to see an ophthalmologist; moreover, the study only involved patients who attended the clinic over a 12-month period.

Keratoconus usually becomes apparent in one eye during adolescence and is slowly progressive, particularly during the second decade, before eventually stabilizing in the third and fourth decade. It may, however, commence later in life and progress or arrest at any age. In up to 90% of cases both corneas eventually become affected.5 Crews et al,6 conducted a retrospective analysis of keratoconic patients and found the mean age at hospital referral to be 28 years. In the present study, the mean age at first referral was 28.6 years. It was not possible to determine the mean age of onset because patients who attended the hospital contact lens department had usually been diagnosed with keratoconus already and been managed by their optometrists for some time before being referred to an ophthalmologist. Keratoconus has been reported in children as young as 6 years old,7 however it rarely develops beyond 30 years of age.8 The age of the patients within our study ranged from 16 to 49 at the time of hospital referral, and from 16 to 69 during the study period.

The reported gender ratios vary for keratoconus. Prior to 1955 authors reported a higher incidence of female sufferers,9,10,11 however, since 1958, there has been a preponderance of male sufferers with an average male to female ratio of 3:2.12,13 Even more recently, this ratio has been reported to be 3:1.14 In the present study, there was again a male preponderance of 8:5.

Keratoconus is a degenerative disorder that leads to thinning and ectasia of the cornea, causing characteristic irregular light reflexes on ophthalmoscopy and retinoscopy or irregular mires on keratometry. The patient develops a progressive, irregular myopic astigmatism causing reduced vision which explains why optometrists are usually the first to be consulted by these patients and hence form the main source of initial hospital referral (72.2%) in our study. This also accounts for the most common presenting visual complaints being those of blurred vision (78%) and poor visual acuity (63%). Keratoconus is rarely unilateral and even in cases where the contralateral eye appears to be clinically normal without any visual symptoms, there will usually be mild changes of steepening seen on computerized video keratography (CVK).15 In our study, 102 patients (78.5%) had bilateral contact lenses fitted, 24 patients (18.5%) had a contact lens fitted in one eye only and four patients (3%) did not have a contact lens in either eye. None of the 24 patients who had monocular contact lenses required a contact lens in the contralateral eye within the 12-month study period and none of the four patients who did not have contact lenses in both eyes required contact lenses in either eye during the study period. The lag time to fit a fellow eye with contact lenses has been reported to be approximately 5.5 years,14,16 and it remains to be seen if the 28 patients in this study will eventually require contact lenses in their presently lens-free eyes.

Eleven eyes of eight patients (6% of all keratoconus patients) in this study had received PK on initial hospital referral with seven out of the 11 eyes (64%) requiring contact lenses post graft. Other studies have reported that between 10–30% of subjects with keratoconus undergo PK,17,18 and the need for contact lens wear after PK has been reported to range from as low as 19%14 to as high as 60%.19 It was not possible for us to determine the mean length of time from diagnosis to PK as our patients had all received PK prior to being seen in the hospital.

Keratoconus is known to be the most common indication for PK in developed countries. The main reasons for keratoconic patients undergoing PK in our study were contact lens intolerance (83%), frequent contact lens displacement (8.5%) and unsatisfactory visual acuity despite good contact lens fit (8.5%) according to the individual visual need of the patients. Dana et al1 confirmed these three main reasons for PK in their study, but their primary cause was found to be unsatisfactory visual acuity of under 20/40 (43%), followed by contact lens intolerance (32%) and frequent lens displacement (13%). Weed et al14 reported their main reason to be contact lens discomfort (67.5%), followed by problems with contact lenses falling out (19%) and poor contact lens visual acuity (13.5%).

After initial hospital referral, 57% of keratoconus patients required refitting of contact lenses due to problems arising from unsatisfactory vision, discomfort or unstable lens fit, all of which are potential causes for PK. However, none of the patients required PK within the study period following hospital referral. Figure 1 shows the different types of contact lenses used during the study period. Two hundred and nineteen eyes (96.1%) were fitted with rigid gas permeable (RGP) lenses which included lenses of spherical, elliptical and cone lens designs. Six eyes (2.7%) were already using Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) lenses when they were first seen in hospital, and as they remained comfortable with the lenses, the patients were kept on wearing PMMA lenses. Two eyes were successfully fitted with soft contact lenses: one eye with a Softperm lens and one eye with a Keratosoft lens. One eye was successfully fitted with a scleral contact lens after having failed all other types of contact lenses. Rigid gas permeable contact lenses have been the mainstay treatment of advanced keratoconus.20 In our contact lens department, the initial choice of lens design is determined by keratometric readings. Eyes with mean K-readings of 6.8 mm and above are usually fitted with spherical RGP lenses such as XL20 and Boston II. More advanced keratoconic eyes with mean K-readings of 6.8–6.0 mm are usually fitted with the bi-elliptical Persecon E Keratoconus (PEK) lens. For very advanced keratoconic eyes with mean K-readings of less than 6.0 mm, the custom conical designs such as the Rose K or McGuire lens are used. Custom designed lenses are used as individually ‘tailored’ lenses that can actually alter the conical shape of keratoconus. Eyes that have failed with all the above choices are tried with aspherical lenses such as Silo II aspheric and Boston Equa, or with soft gas permeable designs such as Softperm and Keratosoft lenses.

We apply the contact lens fitting principle of distributing the weight of the lens between the cone and the more normal peripheral cornea. In cases where the cone is well established, this results in a lens showing an apical contact area of 2–3 mm, an intermediate clearance zone and a mid peripheral contact annulus with standard edge clearance at the periphery. In our study, 87% of patients achieved visual acuity of 6/9 or better with contact lenses. An approximate 59% of eyes (62 out of 116 right eyes and 72 out of 112 left eyes) had improvement in visual acuity of 0.6 logMAR or more. Our patients proved to be enthusiastic contact lens wearers. The mean number of years of contact lens wear was 14.5 years; 96% of patients were able to wear their contact lenses for more than 8 hours per day.

Although keratoconic patients have a reputation of being ‘difficult’,21 this did not appear to be the case with our patients. It is understandable that patients can be initially distressed in view of the debilitating visual loss affecting them at a rather young age. Some centres have now started keratoconus support groups providing great emotional benefits to the patients.

Conclusion

Our study supports the assertion that contact lenses continue to play a predominant role in the management of keratoconus. Various lens designs have enabled us to fit most of our patients with contact lenses successfully.

References

Dana MR, Putz JL, Viana MAG et al. Contact lens failure in keratoconus management. Ophthalmology 1992; 99: 1187–1192

Mannis MJ, Zadnik K . Contact lens fitting in keratoconus. CLAO J 1989; 15: 282–289

Kennedy RH, Bourne WM, Deyer JA . A 48 year clinical and epidemiological study of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol 1986; 101: 267–273

Catch A . Korrelationspathologische Untersuchungen. Albrecht von Graefes Arch Ophth 1938; 138: 866–892

Klintworth GK, Damms T . Corneal dystrophies and keratoconus. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 1995; 6: 44–56

Crews MJ, Driebe WT, Stern GA . The clinical management of keratoconus: a 6 year retrospective study. CLAO J 1994; 20: 194–197

Gretz DC, McDonell PJ . Keratoconus and ocular massage. Am J Ophthalmol 1988; 106: 757–758

Hall KGC . A comprehensive study of keratoconus. Br J Physiol Opt 1963; 20: 215–156

Thomas CI . The Cornea CC Thomas: Springfield, Illinois 1955 pp 233–244

Barth J . Statistik uber 300 Keratokonusfaelle mit 557 befallenden Augen 1948 MD Thesis, University of Zurich

Nuel JP . Keratoconus In: Norris E, Oliver J (eds) System of the Eye Vol IV 1900 pp 249–253

Obrig TE, Salvatori P . Contact Lenses The Chiltern Co: New York 1958 pp 145–146

Thalainen A . Clinical and epidemiological features of keratoconus. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl 1986; 178: 1–64

Weed K, McGhee CNJ . Referral patterns, treatment management and visual outcome in keratoconus. Eye 1998; 12: 663–668

Rabinowitz YS, Nesburn AB, McDonnell PJ . Videokeratography of the fellow eye in unilateral keratoconus. Ophthalmology 1993; 100: 181–186

Reinke AR . Keratoconus: a review of research and current fitting techniques. Int Contact Lens Clin 1975; 2: 66–79

Edrington TB, Zadnik K, Barr JT . Keratoconus. Optom Clin 1995; 4: 65–73

The Australian Corneal Graft Registry 1990 to 1992 report. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1993; 21: 1–48

Smiddy WE, Hamburg TR, Kracher GP, Stark WJ . Keratoconus: contact lens or keratoplasty?. Ophthalmology 1988; 95: 487–492

Bufidis T, Konstas AG, Mamtziou E . The role of computerized corneal topography in rigid gas permeable contact lens fitting. CLAO J 1998; 24: 206–209

Karseras AG, Ruben M . Aetiology of keratoconus. Br J Ophthalmol 1976; 60: 522–525

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, N., Vogt, U. Characteristics and functional outcomes of 130 patients with keratoconus attending a specialist contact lens clinic. Eye 16, 54–59 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700061

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700061

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Current perspectives in the management of keratoconus with contact lenses

Eye (2020)

-

Differential Effects of Hormones on Cellular Metabolism in Keratoconus In Vitro

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Consideration of corneal biomechanics in the diagnosis and management of keratoconus: is it important?

Eye and Vision (2016)

-

Keratokonuslinse

Der Ophthalmologe (2013)

-

The Dundee University Scottish Keratoconus study: demographics, corneal signs, associated diseases, and eye rubbing

Eye (2008)