Abstract

Up to 40% of referrals from primary care to ‘breast cancer family clinics’ prove to be of women whose assessed risk falls below the guidelines' threshold for management in secondary or tertiary care, despite recommendations that they should be screened out at primary care level. A randomised trial, involving 87 such women referred to the Tayside Familial Breast Cancer Service compared two ways of communicating risk information, letter or personal interview. Both were found to be acceptable to referred women and to their family doctors, although the former expressed a slight preference for interview. Only four women returned to their family doctors with continuing concerns about breast cancer. Nevertheless, understanding of information provided by either route was unsatisfactory, with apparent confusion about both absolute and relative risks of breast cancer. Substantial minorities appear to believe that they are at no increased risk at all, or even below the population level of risk, while others remain convinced that their personal risk has been underestimated. Family history record forms, completed by the referred women, preferably with the assistance of relatives, are crucial to full assessment of familial risk but one quarter of women referred to the Tayside Familial Breast Cancer Service currently do not complete and return these forms ahead of their clinic appointment. Further collaboration between primary care and the Breast Cancer Family Service is required to improve provision for concerned women whose risks fall below the threshold for special surveillance and to maximise effective use of the family history record form.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Guidelines published in the UK recommend that women concerned about a family history of breast cancer should be assessed first in a primary care setting and only those whose risk exceeds a specified threshold should be referred to specialist services for counselling, screening and possible intervention (Harper, 1996; SIGN, 1998; Eccles et al, 2000; Haites et al, 2000; NICE, 2004). In reality, however, general practitioners (GPs) find this ‘gatekeeper’ role difficult, both in the UK (Fry et al, 1999; Bankhead et al, 2001; Rose et al, 2001; Walter et al, 2001; Elwyn et al, 2002; Campbell et al, 2003) and elsewhere (Escher and Sappino, 2000). The proportion of referrals to breast cancer family clinics that fall below the required risk threshold has been reported as almost 25% in one large UK-wide survey (Wonderling et al, 2001). For Scottish clinics that figure is 30–40% (Wonderling et al, 2001; Holloway et al, 2004; Reis et al, 2006), the difference probably being explained by greater ease of extension and verification of reported family histories in Scotland through access to the National Cancer Registry and to public records of Births, Marriages and Deaths (Collyer and DeMay, 1997; Brewster et al, 2004). The term ‘low risk’ is commonly used as shorthand, even in some official guidelines, to define those falling below the threshold, although such women are generally at greater risk (up to 1.7 times higher) than women of comparable age with no family history of breast cancer.

From its inception in 1994, the Tayside familial breast cancer clinic (TFBCC) has been a multidisciplinary service run and staffed jointly by the Departments of Genetics, Breast Surgery and Radiology. Before this study began, all women referred to the TBFCC were offered an appointment, even if the family history appeared to place them at ‘low’ risk. When that assessment was confirmed, no further follow-up would be arranged, although clinical examination (sometimes supplemented by mammography), was offered before discharge. Inappropriate inclusion of these ‘lower risk’ women in surveillance programmes probably does not represent cost-effective use of limited resources (Reis et al, 2006). However, the need to ‘convey to individuals, especially those at low risk, accurate information in a sensitive and supportive manner’ must still be met (Harper, 1996). We report the outcome of a randomised trial of two approaches to this objective, together with difficulties encountered and possible solutions.

Methods

Before the start of the study, which ran for 30 months from August 2000, all General Practices in the Tayside catchment area were issued with a breast cancer genetics ‘information pack’ developed by the Cancer Research Campaign (Watson et al, 2001) and modified, with the agreement of the authors, to refer specifically to Scotland. They were also informed by letter and through presentations at GP study days, and other locally arranged seminars, about the functions of the breast cancer family clinic and the planned trial. Continuing information was provided through the website of the Department of Surgical Oncology, University of Dundee, and through reports in the Newsletter of the Tayside Primary Care research Network.

With approval from the Tayside Research Ethics Committee, all women referred to the TBFCC were invited to participate in a trial, comparing provision of information about their familial risk by letter or by personal interview. This would apply only if they were judged to fall below the 1998 SIGN guidelines threshold for inclusion in a regular surveillance programme (SIGN and NICE thresholds are very similar). All referred women also received a standardised Family History Record form with a request to complete it as far as possible, preferably in consultation with relatives, and to return it as the first stage in their risk assessment. That form, together with the GP referral letter, augmented as appropriate in each case (and with relevant informed consent) by checking hospital records, Cancer Registry entries and Registrar General's Records of Births, Marriages and Deaths, provided the basis for a consensus decision, taken by the specialist genetics staff, whether to offer an appointment to the multi-disciplinary counselling/surveillance clinic. Enrolment in the trial thus required written informed consent, a completed Family History Record form and a clear decision that familial risk was below threshold level.

Women who met these criteria were randomised by a genetics associate (using computer-generated random numbers) to receive the information in a personalised letter or to attend the genetics department for an interview (with a genetics associate or nurse specialist) which gave an opportunity for questions to be asked and answered but did not include clinical breast examination or mammography. This was followed-up by a personal letter summarising the discussion. All letters included the information that, despite being below ‘threshold’ level, risk of breast cancer was still real. Women should therefore remain ‘breast aware’, report any breast symptoms promptly to their GP, notify TFBCC of any change in their family history of breast/ovarian cancer and participate in the National Breast Screening Programme from age 50. Letters were copied to the referring GP. The two subgroups were well matched for age and social class, the latter being assessed by postcode.

Three months after the letter or interview, participants in the trial were asked to complete and return a ‘Satisfaction Questionnaire’, based on the instrument used in the Wales ‘TRACE’ study (Brain et al, 2000; Gray et al, 2000). The constituent elements are listed in Table 1. They included standardised and validated measures of psychological health as well as specific reactions to the service received.

Eighteen months after the end of the trial period, all GPs who had referred patients included in the trial were asked to complete and return a short questionnaire to evaluate the service provided and specifically to gather information on whether the women had returned to their family doctors with continuing or fresh concerns about breast cancer.

For data analysis Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS™) software was used.

Results

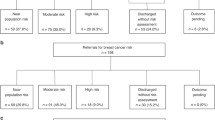

During the study period, 380 women were referred to the TBFCC. Three quarters of these referrals came directly from Primary Care, the remainder being referred from the symptomatic breast clinic. Two hundred and eighty-one (74%) returned their ‘Family History Record’ form but 99 (26%) failed to do so, even after a personal reminder letter. Around half of these brought the form with them when they attended the clinic. Of those who did return the form, 64 (23%) did not give written consent to enter the trial. Only 18 of the 64 actively declined. The remainder simply did not return the consent document or returned it unsigned. Again, many brought the signed form to the multidisciplinary clinic but, even if ‘low’ risk status was confirmed, they could not then be randomised. There were therefore 217 women eligible for the study and, after full assessment as described above, 90 of these (41.5%) were judged to be below the guideline threshold level of genetic risk. They were therefore randomised to ‘letter’ (43) or ‘interview’ (47). Three were subsequently withdrawn; one, assigned to the ‘letter’ group, was found to have a cancer on initial examination at the symptomatic breast clinic (she had been referred there because of vague breast symptoms but family history had been mentioned in the GP letter and onward referral to the cancer family clinic had already been arranged, although no ‘low risk’ letter was actually sent). The other two provided, at interview, new information shifting them to the ‘moderate’ risk category. Among the other 45 ‘low risk’ women interviewed, five gave new information requiring additional checks on family history and three mentioned breast symptoms that led to investigation by a breast surgeon but all remained in the ‘low’ risk category and no significant breast pathology was found. These data are summarised in Figure 1.

Seventy-one of the 87 randomised study patients (81.6%) completed and returned the 3 month ‘satisfaction’ questionnaire. The 87 patients had been referred by 82 GPs, of whom 64 (78%) responded to the follow-up questionnaire (with replies relating to 69 patients – 79%). Analyses of the responses are presented below.

Patient-completed satisfaction questionnaire

Independent samples t-tests were applied to all comparisons.

‘Concerns about breast cancer’ (6 items). Interitem correlations were good so the six were averaged to generate an index of breast cancer concerns. No difference was found between ‘letter’ and ‘face-to-face’ groups, t(69)=−0.636, P=0.527.

‘Actions since referral’ (10 items). Correlations among items varied but all were significant. No differences between ‘letter’ and ‘face-to-face’ groups were significant.

‘Experiences since referral’ (12 items). Correlations between items were all significant so scores were averaged. The difference between averaged scores for ‘letter’ vs ‘face-to-face’ groups did not reach significance, t(69)=−1.676, P=0.098.

‘Personal breast cancer risk estimate’. There was a significant difference between ‘letter’ group (mean=2.0) and ‘face-to-face’ group (mean=2.38), meaning that those receiving their information at interview perceived their risk to be slightly higher than those informed by letter, t(69)=−2.246, P=0.028.

‘Concern about personal breast cancer risk’. No significant difference was found between ‘letter’ and ‘face-to-face’ groups, t(69)=−0.705, P=0.483.

‘Population lifetime risk of breast cancer’. Respondents were invited to estimate population risk in two formats (see Table 1). For one of these, five responses were missing. There was no difference between ‘letter’ and ‘face-to face’ groups for either item, t(64)=.424, P=0.673 and t(69)=0.194, P=0.846.

‘Your own lifetime risk of breast cancer’. Again, this question was posed in two formats. Five responses were missing for one of these. No significant differences between the trial groups were found for either format: t(64)=1.036, P=0.304 and t(69)=−0.249, P=0.804. Both population and personal risk estimates were, however, often wildly inaccurate and there were poor correlations between estimates expressed in the two different formats by the same respondent.

‘Satisfaction with the process’. For five of the 12 items in this set of questions, the ‘face-to-face’ group expressed significantly higher levels of satisfaction than the ‘letter’ group (P range 0.020–0.001) although the mean scores for the ‘letter’ group were in the ‘quite satisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’ range.

‘General Health Questionnaire’. Scores for each of the four subgroups were summed and a t-test carried out on each. None of the differences between ‘letter’ and ‘face-to-face’ groups were significant.

In addition to the above quantifiable responses, women were invited to provide free text answers to open ended questions about their reactions to the information given. The majority either left these text boxes blank or indicated that they were content with the process. However, 7 (4 from the ‘letter’ and three from the ‘interview’ group) made statements indicating that they now believed they were at very low risk of breast cancer – possibly less than that of the general population. (‘I was happy to learn that it doesn't run in families and I am more relaxed about everything’. ‘Quite happy that I am at considerably low risk’. ‘Happy to know my risks are not increased by my mother having developed breast cancer’.) A further seven (four ‘letter’, three ‘interview’) took the opposite view and clearly did not accept the judgement that they were at the lower end of the genetic risk spectrum (‘I cannot feel reassured by the response I received’. ‘I don't know if I believe what you told me; you are giving me a result from statistics which can prove whatever you want to prove. You are not giving me medical facts’.)

GP questionnaires

All but two of the 64 GPs declared themselves completely satisfied with the management of their individual patients. One had some reservations because of the time that elapsed (several months) between his referral and communication of the low assessed risk. Another was dissatisfied because he had no record of the outcome of his referral (although a copy letter had been sent to him).

When asked how they felt about a policy of evaluating risk before offering any clinic appointment and of declining appointments by explanatory letter for those judged to be below ‘threshold’ risk level, 46 of 64 respondents (72%) had no reservations. Seventeen had some reservations and one had serious reservations; where specific reasons were given, these related to the anticipated difficulty for some patients in completing a standard Family History Record form.

No patient had complained to the GP about the way in which their risk status had been assessed or communicated and only four had returned to the GP with concerns about breast cancer in the 18–48 months since receiving their clinic report. Two had fresh complaints of breast discomfort, which were investigated in the regional breast unit and two had simply wished to discuss the information from the genetics clinic. No breast cancers were recorded at that point but one other patient has subsequently developed invasive breast cancer at age 62 years.

Discussion

Our findings show that in deriving the best possible estimate of future cancer risk, face-to-face interview adds little to a detailed family history form (particularly if completed as a collaborative project by several relatives) verified and extended by access to hospital, Cancer Registry and Registrar General's records. Communication of risk information and its implications, however, still presents difficulties.

Patients, whether informed by letter or by interview, seemed to be very uncertain of their actual risk level some 3 months later, at least when invited to give it a numerical value. The discrepancies between two alternative ways of presenting that information may suggest a lack of clarity in the questions or difficulties with numerical notation. Communication of risk in the setting of a breast cancer family clinic is well recognised as a problem area, with no method of communication proven to achieve accurate understanding (Watson et al, 1998; Cull et al, 1999; Braithwaite et al, 2004; Lobb et al, 2005). Furthermore, the free text comments from a number of respondents showed that, despite scrupulous avoidance of the term ‘low risk’ in oral and written communications from the clinic, some feel inappropriately reassured, to the extent of believing their risk may be below that of the general population. Conversely, others evidently cannot accept that their risk does not justify special screening (ineligibility for mammography being resented). Overall, the mean level of satisfaction with the process was acceptable, lying between ‘quite satisfied’ and ‘very satisfied’, although the scores for the ‘interview’ group were significantly better than for those receiving the information by letter. There were no significant differences between ‘letter’ and ‘interview’ in subsequent measures of cancer worry, nor of general psychological health. Despite the recorded preference for face-to-face communication, only four women had returned to their GP with concerns about breast cancer and two of these had been in the ‘interview’ group.

The GP questionnaires revealed no preference for either method of delivering the risk evaluation and, in general, a process whereby referred patients were assessed without necessarily being seen in person at a genetics clinic was considered acceptable.

Conclusion

Given that there must be a threshold level of risk below which clinical and mammographic screening cannot be offered, some disappointment, and hence dissatisfaction with the service is inevitable. Studies, including one from Scotland (Julian-Reynier et al, 1996; Lalloo et al, 1998; McLeish, 2003), have shown that women with a family history of breast cancer place access to regular mammography as their highest priority and indeed, so long as that is provided, they are content to forego specialist genetic assessment and counselling (Brain et al, 2000). The counterpart of that is that some women, when told their risk falls below guidelines' threshold, will resent exclusion from a surveillance programme. Several women used the free text boxes to express disappointment that they had not received any screening or ‘professional examination’ or to comment that they were relieved to know they would receive regular mammography from age 40 years (through a workplace or private healthcare scheme). Our findings in this regard are consistent with those of Scott et al. (2005) who interviewed a selected group of eight women judged to be at below threshold risk level and noted that several of them wished to have their risk ‘up-rated’ so that they would become eligible for screening.

No procedure, short of providing universal access to regular mammography, is likely to satisfy all women and any method of risk assessment will prove flawed in individual cases, as we have found. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that for most women at the lower end of the familial risk spectrum, communication of this information does not require a personal interview. A letter can be an adequate substitute. There is still scope for improvement without incurring unjustifiable costs. For example, the letter might include an invitation to contact the Genetics Centre to discuss continuing concerns. There may be a place for group sessions with specialists such as dieticians, counsellors and breast care nurses, where information on risk reducing ‘lifestyle’ modification may be offered and questions can be answered. Particular attention must also be given to methods of explaining risk, perhaps making use of high quality, specifically designed leaflets. Generic literature available from patient support groups, cancer charities and other clinics may also be useful but it will be important to harmonise the information they contain (Ozakinci et al, 2006).

The concern raised by several GPs about women who find it difficult to complete a Family History Record needs to be addressed. The fact that noncompletion of this form previously guaranteed access to the multidisciplinary clinic was perhaps a disincentive to its proper use and insistence on return of the form as a precondition for access to the cancer family service will almost certainly improve compliance. Rather than simply rejecting referrals in the absence of a completed form, however, it seems preferable to enlist the support of the primary care team in establishing why it has not been returned and in assisting those with genuine difficulties to collect and collate whatever family information may be available.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Bankhead C, Emery J, Qureshi N, Campbell H, Austoker J, Watson E (2001) New developments in genetics – knowledge, attitudes and information needs of practice nurses. Fam Pract 18: 475–486

Brain K, Gray J, Norman P, France E, Angilin C, Barton G, Parsons E, Clarke E, Sweetland H, Tisckowitz M, Myring J, Stansfield K, Webester d, Gower-Thomas K, Daoud R, Gateby C, Monypenny J, Swingland H, Branston L, Sampson J, Roberst E, Newcombe R, Cohen D, Rogers C, Mansel R, Harper P (2000) Randomised trial of a specialist genetic service for familial breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 1345–1351

Braithwaite D, Emery J, Walter F, Prevost AT, Sutton S (2004) Psychological impact of genetic counselling for familial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 96: 122–133

Brewster D, Fordyce A, Black RJ, Scottish Cancer Geneticists (2004) Impact of a cancer registry-based genealogy service to support clinical genetics services. Fam Cancer 3: 139–141

Campbell H, Holloway S, Cetnarskyj R, Anderson E, Rush R, Fry A, Gorman D, Steel M, Porteous M (2003) Referrals of patients with a family history of breast cancer from primary care to cancer genetics services in S E Scotland. Br J Cancer 89: 1650–1656

Collyer S, DeMay R (1997) Public records and recognition of genetic disease in Scotland. Clin Genet 31: 125–131

Cull A, Anderson ED, Campbell S, Mackay J, Smyth E, Steel M (1999) The impact of genetic counselling about breast cancer risk on women's risk perceptions and levels of distress. Br J Cancer 79: 501–508

Eccles DM, Evans DGR, Mackay J, UK Cancer Family Study Group (2000) Guidelines for a genetic risk-based approach to advising women with a family history of breast cancer. J Med Genet 37: 203–209

Elwyn G, Iredale R, Gray J (2002) Reactions of GPs to a triage-controlled referral system for cancer genetics. Fam Pract 19: 65–71

Escher M, Sappino AP (2000) Primary care physicians' knowledge and attitudes towards genetic testing for breast-ovarian cancer predisposition. Ann Oncol 11: 1131–1135

Fry A, Campbell H, Gudmunsdottir H, Rush R, Porteous M, Goeman D, Cull A (1999) GP's views on their role in cancer genetics services and current practice. Fam Pract 16: 468–474

Goldberg DP, Williams P (1988) A Users' Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor. NFER-NELSON

Gray J, Brain K, Norman P, Anglim C, France L, Barton G, Branston L, Parsons E, Clarke A, Sampson J, Roberts E, Newcombe R, Cohen D, Rogers C, Mansel R, Harper P (2000) A model protocol evaluating the introduction of genetic assessment for women with a family history of breast cancer. J Med Genet 37: 192–196

Haites NE, The Cancer genetics subgroup of the Scottish Cancer Group (2000) Guidelines for regional genetics centres on implementation of genetics services for breast, ovarian and colorectal cancer families in Scotland. CME J Gynae Oncol 5: 291–307

Harper P, Genetics and Cancer services (1996) Report of Working Group to the Chief Medical Officer. London: Department of Health

Holloway S, Porteous M, Cetnarskyj R, Anderson E, Rush R, Gorman D, Steel M, Campbell H (2004) Patient satisfaction with two different models of cancer genetic services in south-east Scotland. Br J Cancer 90: 582–589

Julian-Reynier C, Eisinger F, Chabal F, Aurran Y, Nogues C, Vennin P, Bognon Y-J, Machelard-Roumagnac M, Mangard-Loubourtin C, Serin D, Versini S, Mercuri M, Sobol H (1996) Cancer genetics clinics: target populations and consultees' expectations. Eur J Cancer 32A: 398–403

Lalloo F, Boggis CRM, Evans DG, Shenton A, Threlfall AG, Howell A (1998) Screening by mammography, women with a family history of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 34: 937–940

Lerman C, Trock B, Rimer BK, Jepson C, Brody D, Boyce A (1991) Psychological side effects of breast cancer screening. Health Psychol 10: 259–267

Lobb EA, Butow PN, Meiser B, Barratt A, Gaff C, Young MA, Kirk J, Gattas M, Gleeson M, Tucker K (2005) Women's preferences and consultants' communication of risk in consultations about familial breast cancer: impact on patient outcomes. J Med Genet 40: e56

McLeish L (2003) Demands and Needs of Women Attending two Scottish Family History Breast Cancer Clinics. MSc Thesis, University of Manchester: Manchester

NICE (National Institute for Clinical Excellence). Clinical Guideline 14 (2004) The Classification and Care of Women at Risk of Familial Breast Cancer in Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Care. London

Ozakinci G, Humphris G, Steel CM (2006) Provision of breast cancer risk information to women at the lower end of the familial risk spectrum. Community Genet (in press)

Reis MM, Young D, McLeish L, Goudie D, Cook A, Sullivan F, Vysny H, Fordyce A, Black R, Tavakoli M, Steel M (2006) Analysis of referrals to a multi-disciplinary breast cancer genetics clinic: practical and economic considerations. Fam Cancer July 1; [Epub ahead of print]

Rose PW, Watson E, Yudkin P, Emery J, Murphy M, Fuller A, Lucassen A (2001) Referral of patients with a family history of breast/ovarian cancer – GPs' knowledge and expectations. Fam Pract 18: 487–490

Scott S, Prior L, Wood F, Gray J (2005) Repositioning the patient: the implications of being ‘at risk’. Soc Sci Med 60: 1869–1879

SIGN (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network) (1998) Breast Cancer in Women. Edinburgh: SIGN Guideline 29

Walter FM, Kinmonth AL, Hyland F, Murrell P, Marteau TM, Todd C (2001) Experiences and expectations of the new genetics in relation to familial risk of breast cancer: a comparison of the views of GPs and practice nurses. Fam Pract 18: 491–494

Watson E, Clements A, Yudkin P, Rose P, Buckach C, Mackay J, Lucassen A, Austoker J (2001) Evaluation of the impact of two educational interventions on GP management of familial breast/ovarian cancer cases: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract 51: 817–821

Watson M, Duvivier V, Wade Walsh M, Ashely S, Davidson J, Papaikonomou M, Murday V, Sacks N, Eeles R (1998) Family history of breast cancer: what do women understand and recall about their genetic risk? J Med Genet 35: 731–738

Wonderling D, Hopwood P, Cull A, Douglas F, Watson M, Burn J, McPherson K (2001) A descriptive study of UK cancer genetics services: an emerging clinical response to the new genetics. Br J Cancer 85: 166–170

Acknowledgements

The study reported in this paper was supported by a grant from the Scottish Executive Health Department (Chief Scientist Office). We are grateful to Dr Jonathon Gray and colleagues at the Institute of Medical Genetics, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, for helpful advice and for permission to use a modified form of the TRACE questionnaire.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Young, D., McLeish, L., Sullivan, F. et al. Familial breast cancer: management of ‘lower risk’ referrals. Br J Cancer 95, 974–978 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603389

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603389

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

“I have always believed I was at high risk…” The role of expectation in emotional responses to the receipt of an average, moderate or high cancer genetic risk assessment result: a thematic analysis of free-text questionnaire comments

Familial Cancer (2010)

-

How Risk is Perceived, Constructed and Interpreted by Clients in Clinical Genetics, and the Effects on Decision Making: Systematic Review

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2008)