Abstract

In the electrodeposition of metals, a widely used industrial technique, bubbles of gas generated near the cathode can adversely affect the quality of the metal coating. Here we use phase-contrast radiology with synchrotron radiation to witness directly and in real time the accumulation of zinc on hydrogen bubbles. This process explains the origin of the bubble-shaped defects that are common in electrodeposited coatings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Gas bubbles are an important problem in electrodeposition coating. For example, too much hydrogen typically gives rise to porous films with poor adhesion1,2. Surface treatments are often used to solve this problem3,4,5.

The bubble phenomenon has eluded experimental clarification for decades because of a lack of probes with adequate temporal and spatial resolution and sufficient penetration to show the pattern and development of the coating's microstructural detail.

We have used a new real-time technique known as phase-contrast radiology6,7 to demonstrate that zinc can grow directly on gas bubbles, leading to the formation of voids in the coating. The technique, which generates images that reflect differences in refractive index, is more effective than conventional absorption-based radiology.

Phase-contrast radiology depends on coherent X-rays from synchrotron sources6,7. Even with the best sources, however, real-time studies with high spatial resolution are difficult or impossible to carry out. We have solved this problem by using unmonochromatized synchrotron X-rays (that is, X-rays with limited longitudinal coherence)6,7.

Previously, research on bubbles in electrodeposition processes has relied mainly on quantitative measurements of hydrogen formation and ex situ characterization of coatings. The presence of bowl- and tube-shaped voids suggested negative bubble fingerprints8, but no direct evidence corroborated this possibility.

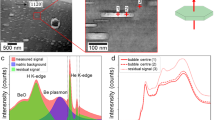

Instead, our results directly link the coating morphology with the hydrogen bubbles. For example, Fig. 1a, b shows the simultaneous formation of bubbles and zinc dendrites. The images reveal that the metal coating is formed directly on the bubble surface, with the zinc dendrites growing out radially (Fig. 1c). Figure 1d shows the microstructure of these dendrites.

a, b, Images (taken 6 s apart) showing growth of zinc dendrites. c, Diagram of radial dendritic growth along the electric-field lines. d, Image showing the microstructure of the dendrites. Radiographs were taken at the Pohang Light Source in Korea and at the Synchrotron Radiation Research Center in Hsinchu, Taiwan. Deposition was carried out in a mini electrochemical cell with a small (about 5 mm) thickness of electrolyte solution between the windows to reduce X-ray absorption, and a variable (about 8 mm) electrode gap. The electrode was covered with epoxy, which prevented conduction, except for the X-ray-detection window. The base solution was 4.8 M KCl and 2.2 M ZnCl2. Scale bars, 300 µm (a, b) and 200 µm (d).

Under varying experimental conditions, we found zinc growing on bubbles not only as dendrites but also as films and in other forms. We did not observe any deposition on bubbles that were not connected to the electrode (Fig. 1a), a finding that rules out electroless deposition.

On the basis of these results, we developed a model to explain the effect of bubbles on metal-coating quality. In this model, a bubble is generated and adheres to the electrode surface; zinc nucleation then occurs at high-surface-energy sites on the electrode–bubble interface, producing microstructures that perturb the local electric field. This enables zinc deposition to extend laterally over the bubble surface, covering the entire bubble. Dendrites then grow radially, following the configuration of the electric field (Fig. 1c).

The metallic film and the dendrite structure are able to stabilize the bubble-related shape. When the deposited metal becomes sufficiently dense, permanent voids are left inside the film, giving rise to defects in the coating.

This mechanism requires a charge-transfer medium. Zinc hydroxide (which, like most metal hydroxides, is an electrical conductor9) is the most likely candidate. Zn(OH)2 can be generated as follows:

Reduction of hydrogen increases the concentration of zinc hydroxide near the cathode surface10,11,12,13. A similar process probably occurs near the bubble surface, resulting in deposition of zinc. We tested this idea by injecting hydrogen into the solution to form hydrogen–electrolyte–electrode interfaces. No zinc was deposited on these interfaces, ruling out the unlikely possibility that the bubbles act directly as charge carriers.

Phase-contrast radiology can be put to several other uses — for example, we have generated dynamic maps of density in the electrolytic solution. Our discovery that metal coatings can literally be built on bubbles finally confirms what has long been suspected.

References

Coleman, D. H., Popov, B. N. & White, R. E. J. Appl. Electrochem. 28, 889–894 (1998).

Monev, M. et al. J. Appl. Electrochem. 28, 1107–1112 (1998).

Manso, M., Jiménez, C., Mrant, C., Herrero, P. & Martínez-Duart, J. M. Biomaterials 21, 1755–1761 (2000).

Chen, J. M. & Wu, J. K. Plating Surface Finish. 10, 74–77 (1992).

Zamanzadeh, M., Allam, A., Kato, C., Ateya, B. & Pickering, H. W. J. Electrochem. Soc. 129, 285–289 (1982).

Hwu, Y. et al. J. Appl. Phys. 86, 4613–4618 (1999).

Margaritondo, G. & Tromba, G. J. Appl. Phys. 85, 3406–3408 (1999).

Yumoto, H., Kinase, Y., Ishihara, M., Baba, N. & Kamei, K. J. Surface Sci. Soc. Jpn 17, 43–48 (1996).

Jayashree, R. S. & Kamath, P. V. J. Power Sources 93, 273–278 (2001).

Brenner, A. Electrodeposition of Alloys: Principles and Practices vols 1, 2 (Academic, New York, 1963).

Elkhatabi, F., Sarret, M. & Muller, C. J. Electroanalyt. Chem. 404, 45–53 (1996).

Younan, M. J. Appl. Electrochem. 30, 55–60 (2000).

Velichenko, A. B., Portillo, J., Alcobé, X., Sarret, M. & Muller, C. Electrochimica Acta 46, 407–414 (2000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, W., Hsu, P., Hwu, Y. et al. Building on bubbles in metal electrodeposition. Nature 417, 139 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/417139a

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/417139a

This article is cited by

-

Effects of ultrasonic field on structure evolution of Ni film electrodeposited by bubble template method for hydrogen evolution electrocatalysis

Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry (2021)

-

The Structure Evolution Mechanism of Ni Films Depending on Hydrogen Evolution Property During Electrodeposition Process

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B (2019)

-

Hierarchical structured nickel–copper hybrids via simple electrodeposition

Journal of Applied Electrochemistry (2018)

-

Size limits the formation of liquid jets during bubble bursting

Nature Communications (2011)

-

Hollow microcapsules for sensing micro-scale flow motion in X-ray imaging method

Microfluidics and Nanofluidics (2009)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.