Abstract

We report on a 74-year-old female patient who was admitted to the hospital because of abdominal pain. She underwent a colonoscopy and a stenosing mass was found in the cecum. Histologic findings in the biopsy specimens were consistent with ischemic colitis. Due to clinical symptoms and the endoscopic and radiologic findings that roused the suspicion that the patient was suffering from a malignant tumor, a right hemicolectomy was performed. Histology of the resection specimen disclosed an inflammation of the veins. It was characterized by a predominantly lymphocytic infiltration of the vessels affecting the veins of the colonic wall and the mesentery. Furthermore, secondary thrombosis with focal venous occlusion was observed. The colon showed extensive ischemic colitis with focal transmural coagulation necrosis. The disease was considered to be idiopathic lymphocytic phlebitis, which is a rare disease of unknown origin. Our patient is well and alive after more than 1 year, supporting the notion that the disease shows a benign course after surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Ischemic colitis and enterocolitis may be caused by a number of diseases, including the occlusion of the main mesenteric vessels and various vasculitis syndromes. The management and prognosis of these lesions is dependent upon the underlying disease, indicating the need to perform a sufficient diagnostic work-up. In particular, vasculitis syndromes have caused a lot of diagnostic consternation because of the heterogeneity of their etiology and pathogenesis. Also, some forms of vasculitis are very rarely observed, thus limiting the clinical experience with these diseases. In the present report, we present a patient with a rare and peculiar type of vasculitis, idiopathic enterocolic lymphocytic phlebitis. We demonstrate histologic and immunohistologic features of this disease and discuss differential diagnoses that include mainly various vasculitis syndromes.

Case Report

A 74-year-old female Caucasian patient was admitted to a hospital in Braunau with abdominal pain and tenderness in the right lower abdominal region. Laboratory investigations disclosed a normal red blood cell count and an increased number of white blood cells (12.100/mm2). The blood chemistry profiles and abdominal and thoracic X-rays were considered normal. The patient received levodopa, tolcapone, and biperiden for therapy of Parkinson's disease. Transabdominal bowel sonography revealed an ill-defined intestinal mass in the ascending colon and cecum. The mass appeared to extend into the paracolic fatty tissue. The patient underwent colonoscopy and a stenosing, tumor-like, polypoid mass was observed. Multiple biopsy specimens were taken and histologic findings were consistent with ischemic colitis. No neoplastic tissue was found. Because of clinical symptoms and the endoscopic and radiologic findings, which were consistent with a malignant tumor, the patient underwent a right hemicolectomy. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient has been well for more than 1 year.

Pathologic Examination

Gross examination revealed the right-sided hemicolectomy specimen. The terminal ileum was 16 cm in length and the colon was 35 cm in length. The colonic resection specimen included the cecum, ascending colon, a proximal part of the transverse colon, and a 3.5 × 11-cm mesocolon. There was a polypoid, partly necrotic-looking, tumor-like mass in the cecum, approximately 5 cm in diameter. Focal patchy hemorrhages were found in the mucosa of the ascending colon.

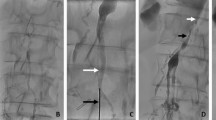

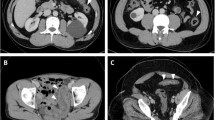

Histology revealed an ischemic colitis with transmural coagulation necrosis in the area of the polypoid mass. The diagnostic feature was a lymphocytic phlebitis of the submucosal and subserosal veins (1). Some of the veins showed a lymphocytic infiltration of the wall with formation of lymphocytic cuffs surrounding the veins (Fig. 1). In some areas, phlebitis did not compromise the lumen of the vessels, whereas in others it was accompanied by subintimal fibroproliferative lesions that focally were occlusive. Some veins showed a fibrinoid necrosis and thrombosis. Giant cells, which have also been observed in lymphocytic phlebitis (2, 3), were not found. The arteries appeared to be normal. Immunohistology revealed that approximately 50% of the inflammatory cells were CD2+, CD3+, CD8+, and CD4− T-cells (Fig. 2). Some of them (approximately 40%) had intracytoplasmic TIA-1+ (T cell restricted intracellular antigen) granules, a marker of T-cells with cytolytic potential (4). Only a minority of T-cells (less than 10%) showed an expression of granzyme B, an activation marker of cytotoxic T-cells (5, 6). The remainder of the cells were B-cells (CD79a+, CD20+, approximately 40%) and histiocytes (CD68+, approximately 10%), but not natural killer cells (CD57−).

DISCUSSION

Enterocolic lymphocytic phlebitis is a rare disease involving small veins of the large, and less frequently the small bowel, gallbladder, and omentum (2) (Table 1). Saraga and Costa (1) coined the term idiopathic enterocolitic lymphocytic phlebitis in 1989, but similar cases have also been reported as mesenteric inflammatory veno-occlusive disease (7). Patients typically present with either a tumor-like mass, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or acute abdomen (2, 3, 8). They show an uneventful clinical course after removal of the diseased bowel. Saraga and Costa (1) suspected an association of this disease with the use of the drug Rutoside, but this has not been found by others, leaving the cause of the disease undefined.

Our patient clearly fulfilled the criteria described by Saraga and Costa (1), showing a predominantly lymphocytic infiltration of intramural tributaries of the mesenteric veins. As others have observed before (1, 17), the lymphocyte population was composed of T-cells and B-cells. In contrast to findings by some (1), a zonal arrangement of B-and T-cells was not observed in our specimens. What we show here for the first time is, that the T-cells are of cytotoxic lineage as revealed by the expression of TIA-1 (T cell restricted intracellular antigen-1), a protein found in cytotoxic granules of T-cells (4). Furthermore, a small subgroup of T-cells also contained granzyme B, another protein of cytotoxic granules, which is found in activated cytotoxic T-cells (5, 6). These findings support the notion that lymphocyte-mediated vascular damage may be of central importance in the pathogenesis of this disease. A fibrinoid necrosis, thrombosis, and occlusion of veins provide sufficient explanation for the ischemic damage of the colon.

Histologic differential diagnoses include drug-induced secondary effects of enterocolic inflammation and ulceration, a hypersensitivity reaction, Schonlein-Henoch purpura, and systemic vasculitis affecting also small veins as seen in systemic lupus erythematodes and Behçet's disease.

Secondary effects of enterocolic inflammation and ulceration can be excluded, as many affected vessels were remote from ulceration and generalized inflammation. Furthermore, the lack of neutrophils in the vascular lesion is not typical of secondary vasculitis. The following vasculitis syndromes can be ruled out, as they either involve also small arteries and/or arterioles and have neutrophils and/or eosinophils: Hypersensitivity reactions and Schonlein-Henoch purpura (9), Churg-Strauss syndrome, panarteritis nodosa, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (10, 11). In Behçet's syndrome, which is one of the most common vasculitis syndromes in which intestinal venulitis with or without accompanying arteriolar involvement has been observed (12), isolated visceral organ involvement has not been reported to our best knowledge. The clinical presentation and the clinical course of our case helped to rule out this vasculitis syndrome.

Two further entities of vascular disease may be interrelated with enterocolitic lymphocytic phlebitis. Myointimal hyperplasia of mesenteric veins (13), which was suggested to represent a burned-out stage of this disease. A feature not supporting such an association is the young age of the patients described (three of four were more than 40 years old). However, myointimal hyperplasia was found in patients with phlebitis and venulitis of mesenteric veins, supporting the notion that those two diseases are interrelated (7). The other disease, which was suggested to be interrelated with enterocolic lymphocytic phlebitis, is necrotizing giant-cell granulomatous phlebitis (3). It was suggested that this peculiar form of vasculitis may be a certain stage or appearance of enterocolic lymphocytic phlebitis. Furthermore, enterocolic lymphocytic phlebitis has to be distinguished from a spontaneous thrombosis of mesenteric veins (14, 15), which may be associated with necrotizing vasculitis (15). This is possible because these two diseases lack the typical lymphocytic infiltration of the veins.

In conclusion, enterocolitic lymphocytic phlebitis is a rare disease of unknown origin, which may present in some cases with tumor-forming ischemic enteritis or colitis. It shows an uneventful course after surgical therapy. Data on conservative treatment have not yet been published.

References

Saraga EP, Costa J . Idiopathic entero-colic lymphocytic phlebitis. A cause of ischemic intestinal necrosis. Am J Surg Pathol 1989;13:303–308.

Burke AP, Sobin LH, Virmani R . Localized vasculitis of the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:338–349.

Stevens SM, Gue S, Finckh ES . Necrotizing and giant cell granulomatous phlebitis of caecum and ascending colon. Pathology 1976;8:259–264.

Anderson P, Nagler-Anderson C, O'Brien C, Levine H, Watkins S, Slayter HS, et al. A monoclonal antibody reactive with a 15-kDa cytoplasmic granule-associated protein defines a subpopulation of CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol 1990;144:574–582.

Kummer JA, Kamp AM, van Katwijk M, Brakenhoff JP, Radosevic K, van Leeuwen AM, et al. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies raised against recombinant human granzymes A and B and showing cross reactions with the natural proteins. J Immunol Methods 1993;163:77–83.

Oberhuber G, Vogelsang H, Stolte M, Muthenthaler S, Kummer AJ, Radaszkiewicz T . Evidence that intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes are activated cytotoxic T cells in celiac disease but not in giardiasis. Am J Pathol 1996;148:1351–1357.

Flaherty MJ, Lie JT, Haggitt RC . Mesenteric inflammatory veno-occlusive disease. A seldom recognized cause of intestinal ischemia. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:779–784.

Haber MM, Burrell M, West AB . Enterocolic lymphocytic phlebitis. Clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features. J Clin Gastroenterol 1993;17:327–332.

Mullick FG, McAllister HA Jr, Wagner BM, Fenoglio JJ Jr . Drug related vasculitis. Clinicopathologic correlations in 30 patients. Hum Pathol 1979;10:313–325.

Helliwell TR, Flook D, Whitworth J, Day DW . Arteritis and venulitis in systemic lupus erythematosus resulting in massive lower intestinal haemorrhage. Histopathology 1985;9:1103–1113.

Lie JT . Illustrated histopathologic classification criteria for selected vasculitis syndromes. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Classification of Vasculitis Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1074–1087.

Lee RG . The colitis of Behcet's syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 1986;10:888–893.

Genta RM, Haggitt RC . Idiopathic myointimal hyperplasia of mesenteric veins. Gastroenterology 1991;101:533–539.

Schneeweiss B, Greul R, Zauner C, Oberhuber G . A man with a leg-vein clot and colonic ulcers. Lancet 1998;351:1628.

Van Way CW 3d, Brockman SK, Rosenfeld L . Spontaneous thrombosis of the mesenteric veins. Ann Surg 1971;173:561–568.

Corsi A, Ribaldi S, Coletti M, Bosman C . Intramural mesenteric venulitis. A new cause of intestinal ischaemia. Virchows Arch 1995;427:65–69.

Endes P, Molnar P . Chronic intestinal lymphocytic microphlebitis. Acta Morphol Hung 1992;40:137–147.

Chergui MH, Vandeperre J, Van Eeckhout P . Enterocolic lymphocytic phlebitis: a case report. Acta Chir Belg 1997;97:293–296.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tuppy, H., Haidenthaler, A., Schandalik, R. et al. Idiopathic Enterocolic Lymphocytic Phlebitis: A Rare Cause of Ischemic Colitis. Mod Pathol 13, 897–899 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880160

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880160

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Not in the Same Vein: Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Malignancy, and Enterocolic Lymphocytic Phlebitis

Digestive Diseases and Sciences (2021)

-

A case report of chronic enterocolic phlebosclerosis; a possible consequence of chronic manifestation of enterocolic phlebitis

Journal of Gastroenterology (2005)