Abstract

Primary adenocarcinoma of the seminal vesicles is an extremely rare neoplasm. Because prompt diagnosis and treatment are associated with improved long-term survival, accurate recognition of this neoplasm is important, particularly when evaluating limited biopsy material. Immunohistochemistry can be used to rule out neoplasms that commonly invade the seminal vesicles, such as prostatic adenocarcinoma. Previous reports have shown that seminal vesicle adenocarcinoma (SVCA) is negative for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and prostate-specific acid phosphatase (PAP); however, little else is known of its immunophenotype. Consequently, we evaluated the utility of cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) and cytokeratin (CK) subsets 7 and 20 for distinguishing SVCA from other neoplasms that enter the differential diagnosis.

Four cases of SVCA—three cases of bladder adenocarcinoma and a rare case of adenocarcinoma arising in a mullerian duct cyst—were immunostained for CA-125, CK7, and CK20. Three of four cases of SVCA were CA-125 positive and CK7 positive. All four cases were CK20 negative. All bladder adenocarcinomas and the mullerian duct cyst adenocarcinoma were CK7 positive and negative for CA-125 and CK20. In addition, CA-125 immunostaining was performed in neoplasms that commonly invade the seminal vesicles, including prostatic adenocarcinoma (n = 40), bladder transitional cell carcinoma (n = 32), and rectal adenocarcinoma (n = 10), and all were negative for this antigen.

In conclusion, the present study has shown that the CK7-positive, CK20-negative, CA-125–positive, PSA/PAP-negative immunophenotype of papillary SVCA is unique and can be used in conjunction with histomorphology to distinguish it from other tumors that enter the differential diagnosis, including prostatic adenocarcinoma (CA-125 negative, PSA/PAP positive), bladder transitional cell carcinoma (CK20 positive, CA-125 negative), rectal adenocarcinoma (CA-125 negative, CK7 negative, CK20 positive), bladder adenocarcinoma (CA-125 negative), and adenocarcinoma arising in a mullerian duct cyst (CA-125 negative).

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Primary adenocarcinoma of the seminal vesicles (SVCA) is a very rare neoplasm with only 48 histologically confirmed cases reported in the European and United States literature (1). The ability to identify SVCA accurately is helpful in clinical management because even in the presence of advanced disease, prompt diagnosis and treatment have been associated with improved long-term survival (1, 2). Specific immunohistochemical markers would be helpful in this differential diagnosis because of the possibility of seminal vesicle invasion by tumors of adjacent organs, particularly prostatic adenocarcinoma. Reported cases of SVCA have consistently demonstrated an absence of staining for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and prostate-specific acid phosphatase (PAP), a property that helps distinguish SVCA from prostatic adenocarcinoma (1, 2). Tumors of other organs adjacent to the seminal vesicles, specifically bladder transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) and rectal adenocarcinoma, can also enter the differential diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains using monoclonal antibodies directed against cytokeratin (CK) subsets 7 and 20 have demonstrated specificity for bladder TCC and rectal adenocarcinoma (3), as bladder TCC is CK7 and CK20 positive, whereas rectal adenocarcinoma demonstrates only CK20 immunoreactivity. To our knowledge, however, no assessment of CK7 and CK20 immunostaining in cases of SVCA has been undertaken.

Recently, cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) staining was reported in a case of SVCA, a finding that was believed to be specific for this tumor (4). There are, however, no large studies that have systematically evaluated CA-125 in tumors that enter the differential diagnosis of SVCA. Other rare tumors may also enter the differential diagnosis of SVCA, including bladder adenocarcinoma and carcinomas arising in mullerian duct cysts.

The goal of this study was to perform a systematic immunohistochemical evaluation to determine the utility of CA-125, CK7, and CK20 immunoreactivity in distinguishing SVCA from other tumors that enter the differential diagnosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case Selection

Paraffin-embedded blocks of formalin-fixed prostatic, bladder, and rectal carcinomas from 82 men were retrieved from the files of the Department of Anatomic Pathology, Gosford Hospital, New South Wales, Australia, in preparation for CA-125 immunostaining. CK7 and CK20 were not performed in these cases because the CK7 and CK20 immunophenotype in prostatic adenocarcinoma, bladder TCC, and rectal adenocarcinoma has been studied in a comprehensive fashion and published elsewhere (3).

Paraffin-embedded formalin-fixed blocks from four previously reported cases of SVCA (1, 5, 6, 7) and one previously reported case of adenocarcinoma arising in a mullerian duct cyst (8) were retrieved. In addition, paraffin-embedded formalin-fixed blocks from three cases of bladder adenocarcinoma from the files of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation were retrieved. All three patients with bladder adenocarcinoma had no evidence of colorectal adenocarcinoma with a minimum of 10 years of follow-up. Tissue sections were prepared for CA-125, CK7, and CK20 immunostaining in all cases of SVCA, bladder adenocarcinoma, and the adenocarcinoma arising in a mullerian duct cyst.

Immunostaining

Sections to be stained for CA-125, CK7, and CK20 were cut 5 μ thick and mounted on Histo grip slides (Lomb Scientific, Sydney, Australia). Sections were deparaffinized, and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 0.5% hydrogen peroxide/absolute methanol. After rinsing, slides for CA-125 staining were microwaved for 10 min at high power and 10 min at 70% power in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer solution at pH 6.0. Slides were placed in Tris buffer, pH 7.6 (TBS) for 5 min and blocked with 3% nonimmune horse serum for 20 min. Excess nonimmune horse serum was drained, and sections were encircled with “PAP” pen (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and incubated using NCL-CA125 monoclonal primary antibody (dilution 1:500; Novocastra, Newcastle, UK), CK7 clone OV-TL 12/30 (dilution 1:40; DAKO), and CK20 clone KS20.8 (dilution 1:20; DAKO). After the sections were washed in TBS, they were incubated in biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 min and washed with TBS. Sections were incubated with peroxidase conjugated streptavidin for 60 min (dilution 1:50 with nonimmune horse serum) and washed in TBS. Peroxidase substrate solution, 3,3-diaminobenzadine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was applied for 5 min and rinsed in TBS. Microwave antigen retrieval was not performed on slides for CK7 and CK20 immunostaining. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and coverslipped. Positive controls were produced from stock tissue blocks known to stain for CA-125, CK7, and CK20.

Immunostain Evaluation

All immunostained slides were reviewed in a blinded fashion by two pathologists. Staining was considered positive if there was definite cytoplasmic immunoreactivity in greater than 50% of tumor cells. Immunostaining intensity was assessed in a semiquantitative fashion and categorized as weak, moderate, or strong.

RESULTS

CA-125 Immunoreactivity in Prostatic Adenocarcinoma, Bladder TCC, and Rectal Adenocarcinoma

Cases of prostatic adenocarcinoma (n = 40), bladder TCC (n = 32), and rectal adenocarcinoma (n = 10) of varying grades and levels of differentiation (Table 1) from men were reviewed in a blinded fashion. Diffuse CA-125 immunoreactivity in greater than 50% of tumor cells was not identified in any of these cases. However, 6 of 40 (15%) prostatic and 3 of 32 (9%) bladder tumors demonstrated focal staining for CA-125 in fewer than 25% of tumor cells.

Immunohistochemical Data in Cases of Seminal Vesicle Adenocarcinoma, Bladder Adenocarcinoma, and Adenocarcinoma Arising in a Mullerian Duct Cyst

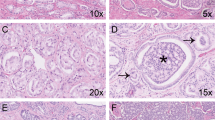

Three of four (75%) cases of SVCA stained for CA-125 (Table 2). All three CA-125–positive tumors were well differentiated and had a predominantly papillary architecture (Figs. 1 and 2). Staining was of at least moderate intensity and was present in more than 95% of tumor cells in all three cases (Fig. 3, Table 2). The single CA-125–negative SVCA was a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.

Three of four cases of SVCA demonstrated a CK7-positive/CK20-negative immunophenotype (Table 2). CK7 staining was diffuse (more than 85% of neoplastic cells) and of strong intensity in all positive cases (Fig. 4). Although not repeated in the present study, all four cases of SVCA evaluated were previously reported to be negative for both PSA and PAP (1, 5, 6, 7).

All three cases of bladder adenocarcinoma and the single case of adenocarcinoma arising in a mullerian duct cyst were CK7 positive, CK20 negative, and CA-125 negative (Table 2). CK7 staining was diffuse (more than 85% of neoplastic cells) and of strong intensity in all positive cases. In addition, all three cases of bladder adenocarcinoma were immunostained for PSA at the time of initial diagnosis, and all were found to be negative. The single case of adenocarcinoma arising in a mullerian duct cyst was previously reported to be negative for PSA and PAP (8).

DISCUSSION

In 1956, Dalgaard and Giertson (9) established the following criteria for a diagnosis of SVCA: (1) the tumor should be a macro- and microscopically verified carcinoma, localized exclusively or mainly to the seminal vesicle; (2) there must be no other primary carcinoma in the body; and (3) the tumor should preferably be a papillary adenocarcinoma that resembles the architecture of the non-neoplastic seminal vesicle. These criteria can be readily applied when evaluating surgical resection specimens. With the use of radiologically guided or endoscopically derived biopsies, however, the pathologist is increasingly called upon to make a diagnosis before definitive surgical resection. In these circumstances, the pathologist will often resort to immunostains to help refine the differential diagnosis. Moreover, even when surgical resection specimens are evaluated, immunostains are still used in conjunction with histomorphology to confirm a diagnosis, particularly when a rare entity such as SVCA is entertained.

CA-125 is a large, highly glycosylated glycoprotein that is found in the epithelium of the fallopian tubes, endometrium, cervix, pleura, peritoneum, and pericardium (10, 11). More than 80% of female genital tract neoplasms demonstrate CA-125 immunoreactivity, including serous, mucinous, endometrioid, and clear cell carcinomas (10, 11, 12). Consequently, CA-125 is commonly used as a marker of mullerian differentiation. Clear cell adenocarcinomas of the lower urinary tract have also been found to demonstrate CA-125 immunoreactivity, suggesting mullerian differentiation in these neoplasms (13, 14). Other tumor types that express CA-125 less frequently include breast, pancreatic, lung, and colon carcinomas (10, 11, 12).

Ohmori et al. (4) reported a case of SVCA that resembled clear cell carcinoma of the female genital tract that stained for CA-125. It is paradoxical that SVCA, a tumor derived from an organ of wolffian duct origin, should demonstrate staining for a marker that is commonly immunoreactive in tumors derived from organs of mullerian duct origin. To our knowledge, only two studies have evaluated CA-125 immunoreactivity in neoplasms of the prostate or bladder (12, 15). Koelma et al. (12) evaluated four cases of bladder TCC using frozen tissue, all of which were negative for CA-125. Gamble et al. (15) evaluated 10 prostatic adenocarcinomas, and although not specifically stated, all tumors were CA-125 negative (A.R. Gamble, personal communication, April 1996).

The present study is the first to evaluate CA-125 staining in a large series of prostatic, bladder, and rectal tumors, lesions that enter the differential diagnosis of SVCA. We found CA-125 immunoreactivity to be an excellent marker of well-differentiated papillary SVCA. In contrast, both prostatic adenocarcinoma and bladder TCC (including Grade 1 tumors with a prominent papillary histomorphology) were consistently CA-125 negative, with a minority of cases showing only weak immunoreactivity limited to fewer than 25% of tumor cells. Given that almost 90% of reported SVCA have demonstrated prominent papillary architecture (1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22), this observation should prove valuable to pathologists who encounter this rare neoplasm. Thus, if the origin of a well-differentiated papillary adenocarcinoma in the region of the seminal vesicles is in question, the combination of CA-125, PSA, and PAP immunostaining, in addition to histologic and gross findings, should help exclude or confirm a diagnosis of papillary SVCA. CA-125 immunoreactivity can also help distinguish SVCA from other rare entities that enter the differential diagnosis. In the present study, all bladder adenocarcinomas and the adenocarcinoma arising in a mullerian duct cyst were also found to be CA-125 negative.

The difficulty in using the aforementioned panel of immunostains arises in tumors that are poorly differentiated. Although PSA and PAP immunoreactivity can be demonstrated in the vast majority of prostatic adenocarcinomas, poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinomas can be negative for these markers in 27% and 19% of cases, respectively (23). However, only 1 to 2% of poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinomas will lack both of these antigens (23). Even in these rare cases, other information, including tumor location, histomorphology, and PSA serology, can aid in clarifying the prostatic origin of the neoplasm (23). In our study, CA-125 immunoreactivity was absent in all cases of poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinoma, as well as in the one case of poorly differentiated SVCA evaluated; consequently, this marker is not useful in differentiating between these two poorly differentiated neoplasms.

Even though prostatic adenocarcinoma is the most common neoplasm to invade the seminal vesicles, bladder TCC and rectal adenocarcinoma can also invade this organ (1, 2). In our study, all rectal adenocarcinomas were CA-125 negative, and only a minority of bladder TCC demonstrated weak CA-125 staining in fewer than 25% of tumor cells. Histologically, some areas of papillary TCC reviewed in our study bore a striking morphologic resemblance to well-differentiated papillary SVCA. In this setting, therefore, CA-125 immunostaining may be useful as an adjunct to routine histology in differentiating between these two neoplasms.

The combined results of two previous studies found CA-125 immunoreactivity in only 4 of 39 (10%) colon adenocarcinomas (5, 24). In the present study, CA-125 staining was absent in all 10 cases of rectal adenocarcinoma tested. Although most cases of rectal adenocarcinoma can be readily distinguished from SVCA by histology alone, poorly differentiated tumors may be more difficult to distinguish from one another. Unfortunately, CA-125 immunostaining is not useful in this setting because of its absence in the single case of poorly differentiated SVCA tested.

Cytokeratins are intermediate filaments that make up the cytoskeleton of human epithelium, of which 20 subsets have been described (25, 26). CK7 and CK20 are subsets with restricted expression depending on the type and differentiation of the epithelium (27, 28). CK7 is characteristic of ductal-type differentiation and is expressed in a variety of adenocarcinomas, such as breast, ovarian (nonmucinous), and prostatic (27). Notably, it is absent in colorectal adenocarcinoma. In contrast, CK20 is a marker of intestinal-type differentiation and is expressed in colorectal and pancreatic adenocarcinoma, as well as in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder and mucinous-type ovarian carcinoma (28).

The specificity of CK7 and CK20 for a particular tumor is greatly enhanced by interpreting the immunostains in conjunction with one another (3). This property is particularly useful for the evaluation of tumors in the region of the seminal vesicles, where tumors entering the differential diagnosis of SVCA, such as prostatic adenocarcinoma, bladder TCC, and rectal adenocarcinoma, have unique coordinate CK7/CK20 immunophenotypes that help distinguish one from the other (3). For instance, even though prostatic adenocarcinoma and bladder TCC both are CK7 positive, only bladder TCC expresses CK20, thus helping distinguish the latter from the former. Furthermore, even though colorectal adenocarcinoma is CK20 positive, the consistent lack of CK7 staining helps to distinguish it from both prostatic adenocarcinoma and bladder TCC, which are CK7 positive.

In the present study, SVCA, bladder adenocarcinoma, and adenocarcinoma arising in a mullerian duct cyst all were CK7 positive and CK20 negative. This coordinate CK7/CK20 immunophenotype is similar to carcinomas that show ductal-type differentiation, such as breast and prostatic adenocarcinoma (3, 25, 26, 27, 28). Therefore, in the region of the seminal vesicles, a CK7/CK20 immunophenotype alone would not distinguish SVCA from prostatic adenocarcinoma. The distinction, however, could be confidently made with the addition of PSA and PAP immunostains. The lack of CK20 immunoreactivity in SVCA is helpful in distinguishing it from colorectal adenocarcinoma and bladder TCC, which are usually CK20 positive.

In summary, whenever papillary SVCA is included in the differential diagnosis of a tumor in the region of the seminal vesicles, a panel of immunohistochemical stains, including CA-125, CK7, CK20, PSA, and PAP, can be very helpful, particularly when only limited biopsy material is evaluated. The CK7-positive, CK20-negative, CA-125–positive, PSA/PAP-negative immunophenotype seen in papillary SVCA is unique and can be used to distinguish it from other tumors that enter the differential diagnosis, including prostatic adenocarcinoma (CA-125 negative, PSA/PAP positive), bladder TCC (CK20 positive, CA-125 negative), rectal adenocarcinoma (CA-125 negative, CK7 negative, CK20 positive), bladder adenocarcinoma (CA-125 negative), and adenocarcinoma arising in a mullerian duct cyst (CA-125 negative).

References

Ormsby AH, Haskell R, Ruthven SE, Mylne GE . Bilateral primary seminal vesicle carcinoma. Pathology 1996; 28: 196–200.

Benson RC, Clark WR, Farrow GM . Carcinoma of the seminal vesicle. J Urol 1984; 132: 483–485.

Wang NP, Zee S, Zarbo RJ, Bacchi CE, Gown AM . Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 defines unique subsets of carcinomas. Appl Immunohistochem 1995; 3: 99–107.

Ohmori T, Okada K, Tabei R, Sugiura K, Mabeshima S, Ohoka H, et al. CA125-producing adenocarcinoma of the seminal vesicle. Pathol Int 1994; 44: 333–337.

Tanaka T, Takeuchi T, Oguchi K, Niwai K, Mori H . Primary adenocarcinoma of the seminal vesicle. Hum Pathol 1987; 146: 200–202.

Chinoy PF, Kulkarni JN . Primary papillary adenocarcinoma of the seminal vesicle. Indian J Cancer 1993; 30: 82–84.

Zenklusen HR, Weymuth G, Rist M, Mihatsch MJ . Carcinosarcoma of the prostate in combination with adenocarcinoma of the prostate and adenocarcinoma of the seminal vesicles. Cancer 1990; 66: 998–1001.

Gilbert RF, Ibarra J, Tansey LW, Shanberg AM . Adenocarcinoma in a mullerian duct cyst. J Urol 1992; 148: 1262–1264.

Dalgaard JB, Giertson JC . Primary carcinoma of the seminal vesicle: case and survey. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1956; 39: 255–267.

Bischof P . What do we know about the origin of the CA-125? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1993; 49: 93–98.

Kenemans P, Yedema CA, Bon GG, von Mensdorff-Pouilly S . CA 125 in gynecological pathology: a review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1993; 49: 115–124.

Koelma IA, Nap M, Rodenburg CJ, Fleuren GJ . The value of tumor marker CA 125 in surgical pathology. Histopathology 1987; 11: 287–294.

Drew PA, Murphy WM, Civantos F, Speights VO . The histogenesis of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the lower urinary tract: case series and review of the literature. Hum Pathol 1996; 27: 248–252.

Young RH, Scully RE . Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the bladder and urethra. Am J Surg Pathol 1985; 9: 816–826.

Gamble AR, Bell JA, Ronan JE, Pearson D, Ellis ID . Use of tumour marker immunoreactivity to identify primary site of metastatic cancer. Br Med J 1993; 306: 295–298.

Oguchi K, Takeuchi T, Kuriyama M, Tanaka T . Primary carcinoma of the seminal vesicle (cross-imaging diagnosis). Br J Urol 1988; 62: 383–384.

Steininger H . Primary cancer of the seminal vesicle. Pathologe 1987; 8: 183–187.

Sussman SK, Dunnick NR, Silverman PM, Cohan RH . Carcinoma of the seminal vesicle: CT appearance. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1986; 10: 519–520.

Kawahara M, Matsuhashi M, Tajima M, Sawamura Y, Matsushima M, Shirai M, et al. Primary carcinoma of the seminal vesicle: diagnosis assisted by sonography. Urology 1988; 32: 269–272.

Davis NS, Merguerian PA, DiMarco PL, Svoretsky PM, Rashid H . Primary adenocarcinoma of the seminal vesicle presenting as bladder tumour. Urology 1988; 32: 466–468.

Langham-Brown JJ, Abercrombie GF . Carcinoma of the seminal vesicle. Br J Urol 1986; 58: 339–340.

Awadalla O, Hunt AC, Miller A . Primary carcinoma of the seminal vesicle. Br J Urol 1968; 40: 574–579.

Epstein JI . PSA and PAP as immunohistochemical markers in prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am 1993; 20: 757–770.

Mainguene C, Aillet G, Kremer M, Chatal JF . Immunohistochemical study of ovarian tumors using the OC 125 monoclonal antibody as a basis for potential in vivo and in vitro applications. J Nucl Med Allied Sci 1986; 30: 19–22.

Moll R, Franke WW, Schiller DL . The catalog of human cytokeratins: patterns of expression in normal epithelia, tumors and cultured cells. Cell 1982; 31: 11–24.

Moll R . Cytokeratins in the histological diagnosis of malignant tumors. Int J Biol Markers 1994; 9: 63–69.

Van Niekerk CC, Jap PHK, Raemakers FCS . Immunohistochemical demonstration of keratin 7 in routinely fixed paraffin-embedded human tissues. J Pathol 1991; 165: 145–152.

Moll R, Lowe A, Laufer J . Cytokeratin 20 in human carcinomas: a new histodiagnostic marker detected by monoclonal antibodies. Am J Pathol 1992; 140: 427–447.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Howard S. Levin for critical reading of the manuscript and Dr. T. Tanaka, Dr. M.J. Mihatsch, Dr. P.F. Chinoy, and Dr. J. Ibarra for providing seminal vesicle adenocarcinoma and mullerian duct cyst adenocarcinoma case material for inclusion in the study. The authors acknowledge the superb secretarial assistance provided by Kathleen Ranney.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ormsby, A., Haskell, R., Jones, D. et al. Primary Seminal Vesicle Carcinoma: An Immunohistochemical Analysis of Four Cases. Mod Pathol 13, 46–51 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880008

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880008

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Seminal vesicle metastasis from transverse colon adenocarcinoma: a unique case report

memo - Magazine of European Medical Oncology (2024)