Abstract

This report deals with 11 examples of renal angiomyolipomas (AML) which appear to include an epithelial element as a part of the neoplasm in the form of gross or microscopic cysts—usually both. There were seven females and four males between the ages of 20 and 70 years with mean age of 45 years. Three of these were known to be symptomatic: intermittent flank pain and gross hematuria for 2 months; recurrent hematuria both before and after flank trauma and a third patient with acute abdomen due to a ruptured tumor blood vessel. Cysts were described in three of the six cases where radiographic data were available. Seven tumors were in the right kidney and four in the left. In gross descriptions, cysts were mentioned in seven and they ranged from 6.0 to 2.0 cm with a median and mean maximal diameter of 5.0 and 4.0 cm, respectively. Microscopically, virtually all of the tumors included multiple smaller cysts and these were lined by flat, cuboidal or columnar epithelium and occasionally hobnail epithelium. There was usually a subepithelial collar of poorly differentiated cells, but the solid element of all tumors was myomatous angiomyolipoma; only one case had any adipose tissue. A dominant histological feature was the prominent lymphatic channels—identical to those of lymphangiomyomas and myomatous or triphasic AMLs. They are much more conspicuous in these cystic cases. Immunohistochemically, all tumors tested were reactive with actin, desmin and HMB-45, with the latter being more intensely positive in the subepithelial collars. Estrogen and progesterone receptors were usually positive, also. The behavior of these lesions appears to be no different from that of other AMLs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Over the years it has been our impression that no benign tumor of the genitourinary system was more often misinterpreted as malignant than the renal angiomyolipoma (AML). The great majority are of course the typical triphasic lesions with smooth muscle, adipose tissue and the characteristic blood vessels but it is very common for the muscle cells to show nuclear variations and/or epithelioid features which cause concern. Those which show very few or no fat cells are frequently regarded as sarcomas or sarcomatoid carcinomas and those with very few muscle cells are often interpreted as liposarcoma—particularly those that arise from the renal capsule and expand entirely into the perinephric soft tissue. Over the past 34 years (1970–2004) we have seen 1064 renal AMLs at the AFIP and only 11 of them show the features to be described here. Although these were not often regarded as malignant only two were recognized as AML (Table 1).

Materials and methods

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides were available on all cases and unstained slides and/or blocks from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue were available for 10 of the 11 cases. Copies of original pathology reports were available on all cases and radiology reports on six. Follow-up was available in five cases. In addition to H&E stains, immunohistochemical studies were performed on 10 cases (Tables 2 and 3).

Results

Clinical Features

Patients ages ranged from 20 to 70 years with median and mean age both of 45 years. Females predominated 7:4 and the right kidney predominated 7:4. Three patients are known to have had symptoms related to the tumor. In case 2 there had been intermitted flank pain and gross hematuria for 2 months. In case 5 the patient had an acute abdomen due to rupture of an AML blood vessel and in case 6 there had been recurrent hematuria for several months both before and after an episode of flank trauma. In three cases the renal tumors were discovered incidentally and in five cases no comment had been made regarding clinical presentation. In six cases we had received information about radiographic findings and cysts were described in three of them. Follow-up information was available on five cases: cases 1, 2, 3 and 7 were without evident disease at 3 years, 9 years, 3 years and 6 months, respectively. Case 4 died of unrelated disease at 3 years. Based upon available clinical information, none of the 11 patients had evidence of tuberous sclerosis or lymphangiomyomatosis. It is not known if any of them had taken estrogen.

Gross Pathology

Cysts were mentioned in seven of the gross descriptions (Figures 1 and 2). They measured from 6.0 to 2.0 cm in maximum diameter with a median of 5.0 cm and a mean of 4.0 cm. Not described as grossly cystic were case 2 which had multiple collapsed cysts microscopically, case 4 (partially cystic) had five or six cysts of indeterminate size, case 5 with the extensive hemorrhage had a microscopic cyst near the ruptured vessel (Figure 3) which extended through the adjacent renal medulla and in case 10, two cysts approximated 1.0 and 0.5 cm microscopically.

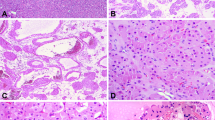

Microscopic Pathology

Most of the cases had multiple smaller cysts, usually about 0.5 cm and less all lined by eosinophilic cells which varied from flat to cuboidal, columnar and/or hobnail. In most cases, but not all, there was a subepithelial layer of small, undifferentiated cells, forming a ‘cambium-like’ layer and peripheral to this the solid element of the tumors consisted of what we will describe here as ‘myomatous angiomyolipoma’—meaning that a lipomatous component was not present (Figures 4, 5 and 6). The one exception was case 10 where the solid tumor was about 20% adipose. Cases 3 and 9 had typical AMLs in remote parts of the kidney (Figure 2). In case 1 the nodular cystic contour (Figure 1) and in case 9 the cystic septations described radiographically, were due to smooth muscle forming septa between cysts (Figures 2 and 7). It was usually possible to demonstrate the thick-walled or cellular vessels characteristic of typical AMLs (Figures 8 and 9) but, in addition to the usual absence of fat cells, a dominant feature in all cases was the prominent branching and curvilinear spaces identical to those seen in lymphangiomyomatosis (Figures 10, 11 and 12). These can usually be seen in the myomatous element of AMLs but they were much more numerous in these cystic lesions.

Incidental findings included multiple papillary adenomas in the adjacent renal cortex in case 7 and, in case 1, a 1.0 cm papillary renal cell carcinoma, type 1, grade 1 was within the wall of the cyst.

Immunohistochemical Findings

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 10 of 11 cases with the following results (positive/negative cases): smooth muscle actin 10/0, desmin 8/0, keratin (cysts) 7/0, HMB-45 10/0, Melan A 2/0, tyrosinase 1/0, MITF 1/0, estrogen receptor 7/2 and progesterone receptor 8/1.

In the other case (case 9), the contributing pathologist found positive SMA, HMB-45 and estrogen and progesterone receptors. It was interesting to note that the HMB-45 reaction was usually much more intense in the subepithelial ‘cambium-like’ zone (Figure 13), and this was often true, also, for the estrogen and progesterone receptors (Figure 14).

Discussion

Two of the more recent cases were sent to us as mixed epithelial–stromal tumors and this will likely continue to be the chief differential diagnostic consideration.1, 2 These are the tumors that previously were classified as cystic hamartomas of the renal pelvis,3, 4, 5 adult mesoblastic nephroma6 or renal pelvic or cortical hamartomas.7 Like the cystic AMLs they occur usually in adult females with mean ages in the forties. Like the cystic AMLs they may have gross and microscopic cysts and they usually have variable quantities of smooth muscle—either in sheets or discrete fascicles. The epithelium consists of tubular or tubulopapillary elements, often aggregated in an adenoma-like morphology with occasional epithelial-lined fibrous nodules. Expanses of stroma may be cellular or acellular fibrous tissue and sheets or collars of a primitive, ‘Mullerian-like’ stromal element. Fat cells may also be present. These are negative for the melanoma markers.

In contrast, the cystic AMLs usually will show the characteristic vessels and, as described above, the slit-like branching and curvilinear spaces are a prominent and constant feature, identical to those seen in lymphangiomyomas and, focally, in most triphasic or myomatous AMLs.8, 9 For this study we have illustrated the recently described monoclonal antibody D2-40 which specifically recognizes human podoplanin and reacts with lymphatic but not blood vascular endothelial cells.10 We have not noted these prominent lymphatic features in other spindle cell tumors of the kidney, but with this new methodology this will likely be specifically addressed in future studies. Lastly, tuberous sclerosis may have renal cysts, but we did not find epithelium with the large voluminous amounts of cytoplasm in the cysts of these 11 cases.11

There remains the question of whether these cysts represent entrapped renal tubular elements. We believe they do not. Two of these cases were interpreted as such and Leung et al12 have described AMLs with entrapped tubular elements showing variable cystic dilatation, but we have not seen anything illustrated which resembles the 11 cases described here. As described by Eble8 we often see entrapped renal tubules in the extreme periphery of AMLs but these do not usually have a particularly cystic appearance. In none of these did the cysts appear to be concentrated in the periphery of the solid tumor. We are not aware of any immunohistochemical study that would distinguish entrapped renal tubules specifically, so this was not attempted. Most persuasive were those cystic AMLs that were entirely external to the kidney with prominent cysts where one would not expect to see entrapped parenchyma. The behavior of these tumors appears to be no different from other AMLs. One of the 11 patients had massive hemorrhage and several of them had hemorrhage in the cyst wall or lumen.

References

Adsay NV, Eble JN, Srigley JR, et al. Mixed epithelial and stromal tumor of the kidney. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:958–970.

Parikh P, Chan TY, Epstein JI, et al. Incidental stromal predominant mixed epithelial-stromal tumors of the kidney. A mimic of intraparenchymal renal leiomyoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2005;129:910–914.

Eble JN, Bonsib SM . Extensively cystic renal neoplasms: cystic nephroma, cystic partially differentiated nephroblastoma, multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma, and cystic hamartomas of renal pelvis. Semin Diagn Pathol 1998;15:2–20.

Pawade J, Soossy GN, Delprado W, et al. Cystic hamartomas of the renal pelvis. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:1169–1175.

Mensch LS, Trainer TD, Plante MK . Cystic hamartoma of the renal pelvis: a rare pathologic entity. Mod Pathol 1999;12:417–421.

Truong LC, Williams R, Ngo T, et al. Adult mesoblastic nephroma: expansion of the morphologic spectrum and review of literature. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:827–839.

Mostofi FK, Davis CJ . Histological Typing of Kidney Tumours. World Health Organization International Histological Classification of Tumours, 2nd edn. Springer: Heidelberg, 1998, p 29.

Eble JN . Angiomyolipoma of kidney. Semin Diagn Pathol 1998;15:21–40.

Martignoni G, Amin MB . Angiomyolipoma. In: Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA (eds). Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. Pathology and Genetics. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. IARC Press: Lyon, 2004, pp 65–67.

Schact V, Dadras SS, Johnson LA, et al. Up-Regulation of the lymphatic marker podoplanin, a mucin-type transmembrane glycoprotein, in human squamous cell carcinomas and germ cell tumors. Am J Pathol 2005;166:913–921.

Bernstein J, Robbins TO, Kissane JM . The renal lesions of tuberous sclerosis. Semin Diagn Pathol 1986;3:97–105.

Leung CS, Srigley JR, Stone CH, et al. Epithelial tubules, cysts and neoplasms in renal angiomyolipoma (AML): a study of 32 cases. Mod Pathol 1998;11:87A, abstract 501.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Denise Young for the immunohistochemistry, Ms Veronica Ferris, MFS and Mr Andy Morataya for the photomicroscopy and digital images, Mr Richard Barton for his work on the tables and Ms Renee Upshur-Tyree for typing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Declaration

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the views of the authors and do not reflect the official views of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, C., Barton, J. & Sesterhenn, I. Cystic angiomyolipoma of the kidney: a clinicopathologic description of 11 cases. Mod Pathol 19, 669–674 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800572

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800572

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts, an unexpected discovery in a gunshot abdomen: a single case report

African Journal of Urology (2023)

-

Evidence of renal angiomyolipoma neoplastic stem cells arising from renal epithelial cells

Nature Communications (2017)

-

Renal angiomyolipoma: a radiological classification and update on recent developments in diagnosis and management

Abdominal Imaging (2014)

-

Cathepsin K expression in the spectrum of perivascular epithelioid cell (PEC) lesions of the kidney

Modern Pathology (2012)

-

PEComas: the past, the present and the future

Virchows Archiv (2008)