Abstract

Study design:

Prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial.

Objectives:

To evaluate the efficacy of topical phenytoin solution in treating pressure ulcers among patients with spinal cord disorders and to evaluate the systemic absorption of topical phenytoin.

Setting:

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Unit, Christian Medical College, Vellore, India.

Methods:

Twenty-eight patients with stage 2 pressure ulcers were randomized to receive either phenytoin solution (5 mg/ml) or normal saline dressing on their ulcers once daily for 15 days. Efficacy of the treatment was determined by assessing the reduction in Pressure Ulcer Scores for Healing (PUSH 3.0), ulcer volume and ulcer size as on day 16. Serum phenytoin concentrations were estimated to determine the systemic absorption of topical phenytoin.

Results:

Statistically insignificant but marginally higher reduction in PUSH 3.0 scores and ulcer size were seen with topical phenytoin treatment. Systemic absorption of topical phenytoin was negligible. No adverse drug events were detected during the study.

Conclusions:

Phenytoin solution is a safe topical agent that accelerates healing of pressure ulcers. However, its efficacy is only slightly more than normal saline treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pressure ulcers are an important cause of morbidity, mortality and extended hospital stay among patients with spinal cord injuries.1 Treating pressure ulcers is expensive at present and the quest for an inexpensive, safe and effective topical agent to treat pressure ulcers continues.2

The antiepileptic agent phenytoin, applied topically, accelerates the healing process in ulcers of various etiologies.2 Despite encouraging results, topical phenytoin is not widely used due to lack of definitive evidence on its efficacy using double-blind randomized clinical trials.2, 3 Concerns regarding optimal dosage form, mode of delivery and systemic absorption of phenytoin following topical application, also need to be addressed.3

In this study, we evaluated the ulcer healing property of topical phenytoin and assessed the systemic absorption of phenytoin following topical application.

Materials and methods

We conducted a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial at the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore, between October 2005 and November 2006. CMC is a tertiary care teaching hospital in south India. The study was approved and monitored by the institutional review board.

Sample size

As there were no previous clinical trials using phenytoin solution for pressure ulcers, we conducted a pilot study with 14 patients in each group and further calculated the sample size based on this study result.

Study sample

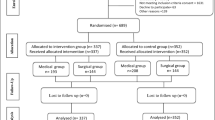

We screened all patients with spinal cord disorders admitted to the rehabilitation ward with pressure ulcers or who developed ulcers during their stay in the ward. Pressure ulcers were classified according to National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel.4 Paraplegic patients aged between 10 and 55 years, presenting with stage 2 pressure ulcers without necrotic tissue were included for the study. Patients with anemia, hypoalbuminemia, elevated serum creatinine, abnormal liver function tests, history of smoking, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, connective tissue disorders and psychiatric illness were excluded. After the baseline assessment twenty-eight patients were found eligible and were enrolled in the study after obtaining written informed consent. Patients were randomly assigned to the treatment and control groups using a computer-generated randomization list. Subsequently, two patients in the treatment group were lost to follow-up because of discharge from the hospital at patient's request. Hence, the final analysis sample comprised 12 patients in the treatment group and 14 patients in the control group (Figure 1).

Interventions

Treatment (phenytoin solution) and control solutions (normal saline) were prepared and labeled using the randomization number by pharmacists of our institutional pharmacy. The nursing staff who administered pressure ulcer dressings were blind to treatment assignment.

Treatment group

Injection phenytoin solution (50 mg/ml, Park-Davis) was diluted using normal saline (0.9% NaCl, CMC pharmacy) to prepare phenytoin solution (5 mg/ml). At this concentration the pH was 7.3–7.4. The preparation was indistinguishable from the normal saline in presentation, color, density, and odor. Fourteen patients received sterile gauge soaked with phenytoin solution for dressing their ulcers once daily for 15 days.

Control group

Fourteen patients received sterile gauge soaked with normal saline for dressing their ulcers once daily for 15 days.

Outcome assessment

The ulcer healing rate was assessed using the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH 3.0).5 PUSH 3.0 scores pressure ulcers from 0 to 17 based on ulcer surface area (length × width), exudate amount and tissue type.5 Reduction in PUSH 3.0 indicates ulcer healing.

To assess the ulcer size, tracings of ulcer perimeter were taken on transparent sheets. Images were scanned and ulcer size was determined using a computer software developed by the Department of Bioengineering, Christian Medical College, Vellore.

To measure ulcer volume, ulcers were initially filled with normal saline up to the brim and then normal saline was withdrawn using a calibrated syringe.

PUSH 3.0 scores, ulcer size and volume measurements were estimated on day 1 before starting the treatment and on day 16. Strict aseptic precautions were taken while measuring ulcer size and ulcer volume. All evaluations were carried out by a single investigator who was blind to the type of intervention.

Blood samples for serum phenytoin measurement were taken in all patients on day 1, before starting the treatment and on day 15, 1.5 h after the last dressing. The serum was extracted and phenytoin concentrations were estimated using high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC).6

Laboratory investigations, including haemogram, serum total protein, serum albumin, blood sugar, serum creatinine and liver function tests were performed at study entry.

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Statistical evaluation

Values were expressed as mean±SD and number (percentage) for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The differences in the PUSH scores, ulcer volume and ulcer size between the two groups were analyzed using independent t-test and Mann–Whitney U test (for normally and non-normally distributed data). P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 11.5 Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

At baseline there were no significant differences in demographic profiles, clinical parameters and functional measures between the two groups (Table 1).

Efficacy

Reductions in PUSH 3.0. scores, ulcer size and ulcer volume were seen when these outcome assessment parameters as on day 16 were compared with the day 1 values. Reductions in PUSH 3.0 scores and ulcer size was marginally higher in the topical phenytoin group while the reduction in ulcer volume was slightly better with normal saline treatment (Table 2). However, difference between the two groups was statistically insignificant (Table 2).

Safety

Serum phenytoin concentrations were less than 0.2 μg/ml, indicating a negligible absorption of phenytoin following topical application. None of the patients reported any local or systemic adverse events during the study.

Discussion

Ulcer healing property of topical phenytoin has been reported from several animal studies7 and clinical trials.8, 9, 10, 11 Proposed actions of phenytoin include accelerated fibroblast proliferation, formation of granulation tissue and deposition of connective tissue components, as well as reduction in collagenase activity and bacterial contamination of the ulcer.3 In most of the clinical trials investigators have used phenytoin powder from the capsules or phenytoin suspensions (2 and 4%)2, 3 since they are convenient to use. However, they contain numerous additional components (eg dyes, flavors) and it is not possible to differentiate the effect of phenytoin from other components of the preparation.2 In addition, finding an inert placebo powder for conducting a double-blind clinical trial is difficult.2 The validity of most of the previous studies is questionable as they were not conducted in randomized, double-blind design.2

Although undiluted injectable phenytoin (50 mg/ml) is suitable for double-blind trials, its high pH (12) can adversely affect the healing process.2 Spaia et al9 reported accelerated ulcer healing with diluted injection phenytoin solution (5 mg/ml). We have used the same methodology (received through a personal communication from Dr Theodoras Eleftheriadis) to prepare the phenytoin solution (5 mg/ml) and conducted our study in a randomized, double-blind method. The other major criticism with some of the previous studies is being the use of topical antiseptics as control treatment.2 Topical antiseptics can adversely affect the healing process.2 We have used normal saline as a control since it supports ulcer healing and is commonly used in pressure ulcer dressing.

Our results suggest that even though topical phenytoin accelerates pressure ulcer healing, in comparison with normal saline treatment it is not statistically significant. Evidence from existing clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of topical phenytoin in treating pressure ulcers is unclear. While Rhodes et al10 reported a significant improvement with phenytoin powder, Hollisaz et al11 found only a marginal benefit with phenytoin cream in treating pressure ulcers. Our study though shows a marginal benefit with phenytoin solution. This discrepancy between the various studies evaluating the pressure ulcer healing property of topical phenytoin, could be because of difference in study design, dosage form and duration of treatment. Hence more evidence, from randomized, double-blind clinical trials with large sample size and long duration of treatment, is required before recommending phenytoin solution for treating pressure ulcers.

Serum phenytoin concentration was less than 0.2 μg/ml in all our samples suggesting a negligible systemic absorption of topical phenytoin. The probability of serum phenytoin concentrations reaching the toxic range (20 μg/ml and above)12 appears to be minimal with topical phenytoin. None of our patients reported any adverse events indicating that topical phenytoin is safe.

Retrospective power analysis revealed the power of our study as 40% and suggested a large sample size for future studies. As the efficacy of topical phenytoin was unclear we chose to treat the patients for 15 days and offer skin grafting as a treatment option for patients with large ulcers after 15 days of treatment. Small duration of treatment may thus be considered as a limitation to our study. To achieve our objectives using a uniform study population we enrolled only patients with stage 2 pressure ulcers awaiting skin graft. The results of this trial cannot be extrapolated to stage 3 or stage 4 pressure ulcers and ulcers with necrotizing tissue.

In summary, the results of this randomized double-blind clinical trial indicate that phenytoin solution is a safe topical agent that accelerates pressure ulcer healing process, although its efficacy is only slightly more than normal saline treatment. Hence, further studies are warranted to better understand the benefit of topical phenytoin solution treatment in patients with pressure ulcers.

References

Nair KPS, Taly AB, Roopa N, Murali T . Pressure ulcers: an unusual complication of indwelling urethral catheter. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 234–236.

Anstead GM, Hart LM, Sunahara JF, Liter ME . Phenytoin in wound healing. Ann Pharmacother 1996; 30: 768–775.

Bhatia A, Prakash S . Topical phenytoin for wound healing. Dermatol Online J 2004; 10: 5.

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure ulcers: incidence, economics, risk assessment. Consensus Development Conference Statement West Dundee. S-N publications Incorporated: Illinois 1989.

Thomas DR et al. Pressure ulcer scale for healing: derivation and validation of the PUSH tool. The PUSH Task Force. Adv Wound Care 1997; 10: 96–101.

Ratnaraj N, Goldberg VD, Hjelm M . Temperature effects on the estimation of free levels of phenytoin carbamazepine and phenobarbitone. Ther Drug Monit 1990; 12: 465–472.

Habibipour S et al. Effect of sodium diphenylhydantoin on skin wound healing in rats. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003; 112: 1620–1627.

Bhatia A, Nanda S, Gupta U, Gupta S, Reddy BS . Topical phenytoin suspension and normal saline in the treatment of leprosy trophic ulcers: a randomized, double-blind, comparative study. J Dermatolog Treat 2004; 15: 321–327.

Spaia S et al. Phenytoin efficacy in treating the diabetic foot ulcer of a haemodialysis patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19: 753.

Rhodes RS, Heyneman CA, Culbertson VL, Wilson SE, Phatak HM . Topical phenytoin treatment of stage II decubitus ulcers in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother 2001; 35: 675–681.

Hollisaz MT, Khedmat H, Yari F . A randomized clinical trial comparing hydrocolloid, phenytoin and simple dressings for the treatment of pressure ulcers. BMC Dermatol 2004; 4: 18.

McNamara JO . Pharmacotherapy of the Epilepsies. In: Brunton LL (ed). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics 11th edn. McGraw-Hill: New York 2005, pp 501–527.

Acknowledgements

We thank CMC fluid research grants committee for funding this study. We also thank Dr Theodoras Eleftheriadis (Department of Nephrology, IKA Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece), Dr Anna Durai (Department of Pharmacy services, CMC), Dr Suresh Devasahayam (Department of Bioengineering, CMC), Dr Jacob Peedicayil (Department of Pharmacology, CMC) and nursing staff (Rehabilitation ward, CMC) for their help in conducting this study and manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Funding: Intramural research funds from Christian Medical College, Vellore

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Subbanna, P., Margaret Shanti, F., George, J. et al. Topical phenytoin solution for treating pressure ulcers: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Spinal Cord 45, 739–743 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102029

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102029

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Phenytoin-loaded bioactive nanoparticles for the treatment of diabetic pressure ulcers: formulation and in vitro/in vivo evaluation

Drug Delivery and Translational Research (2022)

-

Interventions for pressure ulcers: a summary of evidence for prevention and treatment

Spinal Cord (2018)

-

The efficacy of topical phenytoin in the healing of diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized double-blinded trial

International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries (2017)