Abstract

Study design:

Longitudinal; Survey.

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to investigate the natural course of changes in activity patterns, health indicators, life satisfaction, and adjustment over 25-year period among people with spinal cord injury (SCI) in the USA.

Setting:

The preliminary data were collected from a Midwestern United States university hospital of the USA, whereas the follow-up data were collected at a large Southeastern United States rehabilitation hospital.

Method:

The Life Situation Questionnaire was used to identify changes in education/employment, activities, medical treatments, adjustment, and life satisfaction.

Results:

Adjustment scores, satisfaction with employment, satisfaction with finances, years of education, and employment indicators significantly improved over time. In contrast, satisfaction with sex life, satisfaction with health, and then number of weekly visitors significantly decreased and the number of nonroutine medical visits and days hospitalized within 2 years prior to the study significantly increased over the 25-year period.

Conclusion:

Given the mixed pattern of favorable and unfavorable changes, the findings challenge the assumption that aging will inevitably be associated with the overall decline in outcomes and quality of life.

Sponsorship:

This research was supported by field initiated grants from the National Institute for Disability and Rehabilitation Research of the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services (#H133G970111 & H133G010009).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prior to World War II, people with spinal cord injuries (SCIs) were not likely to survive beyond a relatively short period of time. With advances in medicine, longevity increased and has continued to increase over the decades since this time.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 As a result of the increased longevity, there has been an increased focus on long-term outcomes that impact the lives of people living with SCI in the community.

There has been a more recent emphasis on studies of the natural course of aging after as SCI. Despite these new studies, there continues to be insufficient research using longitudinal methods over extensive lengths of time. However, some recent longitudinal studies have been conducted, including those that utilize British and Canadian participant samples.7 Although multinational studies of SCI outcomes are rare, it is possible to link together findings from studies that use participant samples from different countries in order to identify both commonalities and differences in outcomes globally.

Cross-sectional studies

There have been numerous cross-sectional studies examining the effects of aging on individuals with SCI.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 In their 1990 study, DeVivo et al11 examined the influence of age at SCI on rehabilitation outcomes. It was found that individuals who were at least 61 years old at the time of injury were more likely to have developed pneumonia, experience a gastrointestinal hemorrhage, develop pulmonary emboli and have renal stones prior to their first discharge than individuals who were 16–30 years at the time of injury. Individuals over 61 years were also found to be more likely to be rehospitalized during the second year postinjury, to require ventilatory support and to be discharged to a nursing home than those who were 16–30 years at the time of injury. In looking at changes 10 and 15 years postinjury, Cushman and Hasset14 found ability to live in a preferred situation to be most related to life satisfaction. They also found participants with paraplegia to report more negative changes in function than their tetraplegic counterparts. Similarly, when examining functional changes over time in individuals 20 or more years postinjury, significant differences as a function of age and injury severity showed that the need for physical assistance from others had increased, as well as needing additional help with activities of daily living (ie those with cervical injuries needed more help at a younger age and those who were older needed more help in general).8

In recent years, there has been a shift as researchers have started to examine aging differences by gender. It has been found that women consider their aging process to be accelerated, though men report significantly more overall health problems associated with aging with SCI.7, 16 This study also found men to report significantly more diabetes and health problems in general while women reported significantly more days affected by pressure ulcers, fatigue, transportation problems, and pain associated with ADLs. Likewise, being female has been found to be associated with needing more assistance with ADLs.17 While cross-sectional studies do provide valuable insight into aging with SCI, longitudinal studies have the ability to examine changes over time in the same individuals, allowing researchers to determine when and how changes can take place.

In a commendable multinational study, aging was investigated among participants from three countries: Great Britain, United States, and Canada. The findings suggested that American participants had a better psychological profile and fewer health and disability-related problems overall, in contrast to Canadian and British participants. The Canadian participants reported more health and disability-related complications, including problems with bowel, pain, and fatigue. The British group reported intermediate outcomes that included viewer concerns with joint pain and premature aging.16

Longitudinal studies

Recently, Krause examined longitudinal data over a 20-year period. In this investigation, there were numerous findings including identification of longitudinal declines in subjective well being over the previous decade that appeared to be most attributable to environmental change over that period of time; a positive correlation between life adjustment and time since injury, even up to 30 years or more postinjury; identification of seven underlying dimensions of subjective well-being; and identification of different patterns of employment and subjective well-being outcomes based on racial/ethnic group membership.3, 18, 19, 20 In a recent study of community integration of British, American, and Canadian participants with SCI of more than 20 years, it was found that community integration decreased over time in terms of physical independence, mobility, employment, and social integration. Life satisfaction decreased as well. Interestingly, though, overall, economic standing of the participants increased over the years.21 Along those same lines, a study of 439 persons 15 years postinjury, concluded that longitudinal analyses allow for the development of prediction models for various long-term outcomes.22

In regards to aging and gender differences, it has been found that men and women rated quality of life (QOL) equally. QOL has been found to be affected both directly and indirectly by age, health, and perceptions of aging.23 It is clear that longitudinal investigations of aging with a SCI provide much more in depth information into the lives of individuals living with SCI.

Time-sequential studies

In a time-sequential study examining the role or chronologic age, time since injury, and environmental changed in adjustment over 11 years, it was found that adjustment does improve with increasing time since injury, and decreases with increasing age.24 This study found that activity was strongly related to chronologic age (negatively correlated with age), while medical stability was more strongly related to time since injury. In comparing the participants at two time points, results suggested better adjustment (increased sitting tolerance, self-rated current adjustment and predicted future adjustment) at the second time point was reflective of environmental changes between the two time points.

In a similarly designed study, Krause and Sternberg examined aging and adjustment following SCI and the role of chronologic age, time since injury, and environmental change.25 In this study, time since injury was positively correlated with adjustment, while chronologic age was negatively correlated with adjustment. This study is notable; however, in that it found that environmental change over time was associated with deterioration in subjective well-being. This study suggests that an individual's adjustment over time is significantly influenced by environmental changes, which fluctuate over time.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to identify how indicators of employment, health, life satisfaction, and adjustment have changed over a 25-year period among participants with SCI from United States as measured by both level of adjustment (mean differences) and rank-ordering of individuals on adjustment variables (correlational). Patterns of attrition were analyzed to identify systematic differences between respondents and nonrespondents.

Method

Participants

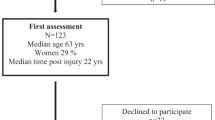

All former and active patients with SCI who had received renal function services at a large Midwestern University hospital clinic in the United States of America prior to 1974 comprised the initial participant pool. To be eligible for the study, participants met the following three screening criteria: (1) traumatic SCI, (2) at least 18 years of age, and (3) a minimum of 2 years postinjury. There were initially 256 respondents in 1974, with an 85% response rate. Of these, there were 95 respondents 25 years later (37%), 36 refused to participate (14%), 77 were deceased (30%), and 46 could not be located (18%). The adjusted response rate was 53% when excluding all those who were deceased and 71% when excluding all those who were either deceased or could not be located.

The mean age of the respondents was 53.8 years (SD=9.2) at the time of the 25-year follow-up (including only the 95 participants). Participants averaged 32.2 years since injury (SD=5.6). In all, 83% were male and 70.5% had quadriplegia with the majority reporting no sensation or movement below the level of injury (34%). All of the respondents were Caucasian. A total of 51% of the participants were working in 1998.

Procedures

Cover letters were sent to potential participants to describe the study prior to transmittal of actual materials. The Life Situation Questionnaire (LSQ) was sent out 4–6 weeks later. Follow-up mailings and phone calls were utilized to build participation among those who initially did not return the questionnaires. Although the LSQ has been revised on several occasions, only the components that remained identical since the first stage of the study in 1974 were used in the current report. Participants were offered a $20.00 stipend to participate in the 25-year follow-up.

Instruments

The LSQ was developed in 1974 to measure the mostly objective aspects of individuals lives after SCI26 as few outcome studies had been conducted at the time of its development. Subsequent revisions were made to expand the number of variables measured with a particular emphasis on increasing the number of variables measuring subjective well-being.6, 19, 20, 27 The current paper focuses only on items that were used consistently throughout the 25-year study.

There were five sets of items including the following: (a) education and employment, (b) activities/participation, (c) medical treatments, (d) adjustment, and (e) life satisfaction. Employment was defined as ‘working for pay’ and was assessed by the number of hours per week an individual spent working and the number of years at their current job. Education was evaluated by asking participants to provide the total number of years of education. Activity patterns included the number of weekly visitors; frequency of weekly outings; and sitting tolerance. A third set tapped the extent to which participants sought medical care within the 2 years prior to the study including the number of nonroutine doctor visits; number of hospitalizations; and days hospitalized. Activity items and medical items were presented as multiple choice, grouped frequencies (eg, the choices for the number of weekly visitors and outings were: rarely; one to three times per month; one to two times per week; three or more times per week). These were treated as continuous scaled data in the current study. With regards to psychological outcomes, participants were asked to rate their adjustment and satisfaction with life. Two 10-point adjustment scales were included. The first scale asked participants to rate their current adjustment, whereas the second scale required them to predict what their adjustment would be in 5 years. In addition, they were asked to rate their satisfaction with six areas of life (living arrangements, employment, finances, social life, sex life, and general health), each on a 5-point scale with 1 being very dissatisfied and 5 being very satisfied (they were actually presented in the opposite fashion on the questionnaire starting in 1974 and maintained that way to ensure consistency, but reversed in the analyses for clarity of presentation).

Analyses

In the first analysis, we compared those participants who remained in the study since 1974 (n=95) with those who dropped out of the study by 1998 (n=161) on all biographic (eg, age, gender), injury (level, years since onset), and outcome variables (eg, life satisfaction, employment, adjustment). t-tests were used to make comparisons on continuous variables such as age, age at injury onset, and life satisfaction; whereas the χ2 statistic was used to test for differences between respondents and nonrespondents on categorical variables.

In the primary set analyses, each outcome variable was compared between occasions to identify changes in mean scores for continuous variables or percentages for categorical variables such as employment status. Paired t-tests were used to identify changes in outcomes between 1974 and 1998 for all continuous variables. There was no correction for multiple t-tests to identify even the most modest trends in changes between the two occasions in outcomes.

Hypotheses

-

1

Compared with respondents, those who did not respond at follow-up will have reported less favorable outcomes during the first time the measurement (ie, attrition will be selective).

-

2

Over the 25-year period, there will be an increase in indicators of vocational activity.

-

3

Health status, as indicated by medical treatments, will decline over the 25-year period.

-

4

Changes in satisfaction with life will be consistent with actual changes in patterns of related outcomes (increased satisfaction with employment; decreased satisfaction with health)

-

5

There will only be a modest correlation between responses at time 1 and 2.

Results

Attrition

Attrition analyses between the respondents and nonrespondents identified several significant differences (Table 1). Respondents were younger both at the time of the 1974 data collection, (t (252)=−5.54, P⩽0.001), and at injury onset (t (525)=−4.17, P⩽0.001), had lived fewer years postinjury at that time (t (254)=−3.05, P⩽0.01), and were more likely to have cervical injuries than nonrespondents (χ2=10.23, P⩽0.01) (Table 2). Respondents also reported more years of education (t (185)=2.94, P⩽0.01), greater satisfaction with health (t (249)=2.38, P⩽0.01), and predicted their overall adjustment would be better in 5 years (t (227)=1.92, P⩽0.05), and had a greater sitting tolerance (t (251)=2.35, P⩽0.05) and reported more frequent social outings (t (248)=2.73, P⩽0.01).

Changes in level of adjustment over time

Table 3 summarizes the results between the two times of measurement on the 18 items. Years of education increased from 13.6 to 15.0 years (t=−5.72, P⩽0.001). The employment rate increased from 44 to 52%, with an even greater margin when considering only those below the traditional retirement age of 65 years (45% 58%). Across the whole sample, hours per week spent working (0 h for those not employed) increased from 10.7 to 18.2, t (87)=−3.37, P⩽0.001 (there were too few cases who were employed on both occasions, n=26 to make comparisons). Years employed at the current job increased from 3.6 to 17.7 years over the 25-year period, t (25)=−6.89, P⩽0.001.

The number of weekly visitors per week decreased between the two times of measurement (t=2.64, P⩽0.01), as did the number of weekly outings (t=3.32, P⩽0.001) whereas sitting tolerance remained unchanged. With regards to medical treatments, the number of nonroutine physician visits increased between the two times of measurement (t=−2.57, P⩽0.01), while the number of days hospitalized decreased (t=2.59, P⩽0.01). There were no significant differences in the number of hospitalizations.

Four of the six life satisfaction variables significantly changed over the 25-year period. Whereas satisfaction with employment increased (t=−2.76, P<0.01), satisfaction with health, social life, and sex life decreased over the 25-year period (t=2.25, P⩽0.05; t=2.53, P⩽0.1; t=2.35, P⩽0.05, respectively). Current self-rated adjustment also increased between the two times and measurement from 7.7 to 8.3, (t=−2.32, P⩽0.05).

Correlations between occasions

The strength of the association between the two times of measurement varied considerably between the outcome areas. The three activity variables (indicators of participation) were all significantly correlated between the two times and measurement, with the correlations ranging from 0.23 for the frequency of visitors to 0.43 for sitting tolerance. Of the three indicators of recent medical history, only the number of times hospitalized was significantly correlated between the two occasions (r=+0.23). For psychological variables, only four of the life satisfaction variables were significantly correlated between the two times of measurement and these correlations ranged between 0.24 and 0.35. The highest correlations were for satisfaction with social life and sex life (both were 0.35), with lower correlations observed for satisfaction with finances (r=+0.24) and satisfaction with health (r=+0.25). Self-rated adjustment was also significantly correlated between the two times of measurement (r=+0.40), although predicted adjustment in 5 years was not. Of the employment variables, the number of hours spent working was significantly correlated between the two occasions (r=+0.22), but years employed at the same job was not. Years of education was highly correlated between the two occasions (r=+0.75), but the measures are not independent since a participant may only increase the number of years education.

Discussion

The current study was designed to identify the natural course of aging over a 25-year period among individuals with SCI in the United States. The design was straightforward, as outcome measures were compared across the two occasions to identify the degree to which each outcome changed for the full cohort (ie, comparisons of changes in mean levels) as well as the degree to which individuals who rated high or low on a particular outcome maintained their relative position over the 25-year period compared with other participants (correlational analyses). The first type of data addressed the natural course of change in outcomes over time as people have aged during this particular time period with SCI, whereas the latter data addressed the stability of individual differences and outcomes over 25 years.

Summary of major findings

The majority of study hypotheses were confirmed. There was no imminent pattern of decline across all outcomes among the study participants, even though their average age was 54 years and an average of 32 years had passed since the onset of their injury. An inspection of the changes in means suggested that participants lives clearly did change over the 25-year period, yet the nature of changes were mixed between the enhancements and declines. Employment outcomes clearly improved over the 25 years, as the employment rate increased, satisfaction with employment improved (supporting hypotheses 2–4), and there was greater stability in terms of tenure at the current job (indicating very little changing of jobs). This favorable change in satisfaction, as well as increases in self-rated adjustment, would suggest an increase in subjective well-being over time, except that it is also clear that satisfaction with other areas of life declined.

Participants reported diminished satisfaction with their social lives, sex lives, and their health. They also reported increases in physician visits, but no changes in number of hospitalizations or days hospitalized (partially supporting hypothesis 3). There were two substantial changes in activity patterns, a decrease in the number of outings and a reduction of weekly visitors. While these are both important changes, they do not appear to have a significant impact on the individuals' overall well-being and life satisfaction. In summary, there appeared to be great stability in terms of participants ability to retain their employment and continue to adapt to the changes brought about by aging with SCI; yet, there were declines in health and social activities that were associated with diminished satisfaction with particular areas of life.

The current findings augment the existing literature by suggesting that, despite having lived an average of more than 32 years with SCI, declines in well-being are not universal to all areas of life. These findings are generally consistent to the findings of McColl and associates in their study of British, American, and Canadian participants, except that overall the findings appear to be a bit more favorable in our study. Taken together, economic and vocational factors appear to improve rather than decline with aging, whereas other aspects of participation appear to decline. Satisfaction appears to decline somewhat in most areas. Since McColl and associates also found that participants from United States fared somewhat better than those from Great Britain and substantially better than those from Canada, we must acknowledge that aging may present different obstacles in different environments.16 Our sample was from the state of Minnesota which has perhaps the most favorable policies and support services for people with disabling conditions of any of the United States, further suggesting that a strong support of environment may have operated to insulate participants against the impact of aging. Nevertheless, the current and other longitudinal studies clearly suggest that age-related changes in multiple outcomes are to be expected after SCI that have the potential to substantially change individual's lives.

Attrition

It must be noted that the analysis of patterns of attrition suggest that individuals who were older, older at the time of injury, had been injured for a longer period of time, had the least active pattern of participation, had the least satisfaction with their health and had poorer predicted adjustment were more likely to have died or otherwise left the study over the 25-year period (supporting hypothesis 1). Therefore, the gains observed over time in the current cohort may reflect characteristics of individuals who have the greatest abilities to adapt to the changing demands imposed by SCI and they may not be represented of the broad spectrum of individuals with new SCIs. In sum, the pattern of mean changes over time suggest improving vocational, financial, and overall psychosocial adjustment among survivors; yet, a clear decline in health and function with an associated increase in the need for medical services is also defined.

The correlational analyses suggest a great deal of change in the amount of stability in ordering of individuals on each variable across the 25-year period. The outcomes in which the greatest degree of stability was observed were those related to activity patterns and satisfaction with certain areas of life (ie, social life and sex life). The stability of these findings over the 25 years may relate to personality characteristics, such as sociability. In contrast, there was very little continuity in medical treatments between the two times of measurement, suggesting that either there were few individuals who had recurrent/chronic medical or health issues across both times of measurement, or, individuals with substantial medical complications were more likely to have died over the 25-year period and therefore not have taken part in the most recent follow-up data collection.

Implications for counselors and psychologists

Rehabilitation professionals who counsel people who have SCI may use the current findings to direct certain aspects of their practice. For instance, vocational counselors may view the current results as supporting the importance of ongoing efforts to help individuals maintain their employment as they age. Clearly, efforts to support maintenance of employment are justified given the number of years participants average working at the same job, the extent to which overall levels of education increase, and the overall increase in number of hours spent per week working. Being employed also has obvious benefits for the maintenance or increase of satisfaction in other areas, such as finances. The current study findings have raised questions as to the extent and nature of resources required to help individuals maintain their employment, as additional supports are likely necessary in light of age-related changes in health and function.

Professionals who work in medical settings should note the decline in the health and increased likelihood of need for medical treatments and perhaps even lengthy hospitalizations among persons aging with SCI. Although these may not impact the majority of people as they age with SCI, they represent part of the natural course of aging and clients may benefit from attention to these issues.

Lastly, there was a clear pattern for diminished satisfaction with social life and sex life. People who have aged substantially since their preliminary rehabilitation may not have access to or knowledge of resources that have been developed that may enhance their social or sexual functioning. They may also lack access to rehabilitation professionals, or feel uncomfortable or embarrassed to seek new information in these areas.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the current study. First, the LSQ was limited in both the breadth of content coverage and the adequacy of its measurement of content areas. Furthermore, the measures of recent medical history and activity patterns were limited by the group frequencies, that is, multiple choice responses that were used during the preliminary stage in the study decreased our power to identify significant changes. These issues are a common problem in all longitudinal studies, as the methodology and instrumentation used during the preliminary phase of the study would not meet the more rigorous standards for measures commonly used today. Yet, 25 years ago the LSQ represented one of the first attempts to assess outcomes among individuals or living in the community with SCI. Later revisions to the LSQ have compensated for these limitations and are of value in other analyses, but not over this 25-year interval of time.18, 24, 28, 29

Second, although there was an appropriate balance of participants based on gender, because of the geographic location in which the sample was identified there were no racial–ethnic minorities. This limitation has been addressed in subsequent studies that have specifically addressed minority issues.20, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35

Third, we chose not to correct for multiple statistical tests. This inflated the likelihood of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is indeed correct. However, we believe that this was justified given the importance of detecting relatively small changes over time and the focus on looking at patterns of change.

Lastly, attrition due to all causes was relatively substantial over the 25-year period, even though the effective response rates were extremely high. This is an inherent limitation of longitudinal designs, as the most common source of attrition was mortality rather than refusal to respond at every point in the study. This issue is magnified with a study of a population, such as persons with SCI, where life expectancy is diminished to some degree.

Future research

There is a need for more research to identify explanatory factors that account for changes in outcomes over time. One of the more prominent needs is to identify the nature of resources and supports that allow people to maintain their employment as they age with SCI. We also need to know more about the timing of when individuals leave the workforce, whether it is earlier than with nondisabled workers, and the factors that precipitate their departure. Once these factors have been identified, rehabilitation counselors and psychologists will be in a better position to address these needs. A closer working relationship between the researcher and practitioner is needed if we are to be able to successfully identify the appropriate research questions, generate data that helps to answer these questions, and translate these findings into successful rehabilitation practices that enhance the QOL of people with SCI and other disabling conditions.

References

Strauss D, DeVivo MJ, Shavelle R . Long-term mortality risk after spinal cord injury. J Insurance Med 2000; 32: 11–16.

DeVivo MJ, Krause JS, Lammertse DP . Recent trends in mortality and causes of death among persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab 1999; 80: 1411–1419.

Krause JS, Sternberg M, Lottes S, Maides J . Mortality after spinal cord injury: an 11-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997; 78: 815–821.

DeVivo MJ, Stover SL . Long term survival and causes of death. In: Stover SL, DeLisa JA, Whiteneck GG (eds). Spinal Cord Injury: Clinical Outcomes from the Model Systems. Aspen; Gaithersburg, MD 1995, pp 289–316.

Whiteneck GG, Charlifue SW, Frankel HL, Fraser MH, Gardner BP, Gerhart MS . Mortality, morbidity and psychosocial outcomes of persons spinal cord injured more than 20 years ago. Paraplegia 1992; 30: 616–630.

Krause JS . Survival following spinal cord injury: a fifteen-year prospective study. Rehabil Psychol 1991; 36: 89–98.

McColl MA, Charlifue S, Glass C, Lawson N, Savic G . Aging, gender, and spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 363–367.

Gerhart KA, Bergstrom E, Charlifue SW, Menter RR, Whiteneck GG . Long-term spinal cord injury: functional changes over time. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993; 74: 1030–1034.

Menter RR et al. Impairment, disability, handicap and medical expenses of persons aging with spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1991; 29: 613–619.

Menter R, Hudson LM . Effects of age at injury and the aging process. In: Stover SL, DeLisa JA, Whiteneck GG (eds). Spinal Cord Injury: Clinical Outcomes from the Model Systems. Aspen Publications; Gaitersburg, MD 1995, pp 277–288.

DeVivo MJ, Kartus PL, Rutt RD, Stover SL, Fine PR . The influence of age at time of spinal cord injury on rehabilitation outcome. Arch Neurol 1990; 47: 687–691.

Roth EJ, Lovell L, Heinemann AW, Lee MY, Yarkony GM . The older adult with a spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1992; 30: 520–526.

Lammertse DP . Aging with spinal cord injury: considerations in the management of younger patients. Topics Spinal Cord Injury Rehabil 2000; 6: 176–181.

Cushman L, Hassett J . Spinal cord injury: 10 and 15 years after. Paraplegia 1992; 30: 690–696.

Pentland W, McColl MA, Rosenthal C . The effect of aging and duration of disability on long term health outcomes following spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1995; 33: 367–373.

McColl MA, Charlifue S, Glass C, Savic G, Meehan M . International differences in ageing and spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2002; 40: 128–136.

Liem NR, McColl MA, King W, Smith KM . Aging with a spinal cord injury: factors associated with the need for more help with activities of daily living. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1567–1577.

Krause JS . Changes in adjustment after spinal cord injury: a 20-year longitudinal study. Rehabil Psychol 1998; 43: 41–55.

Krause JS . Dimensions of subjective well-being after spinal cord injury: an empirical analysis by gender and race/ethnicity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 900–909.

Krause JS . Subjective well-being after spinal cord injury: relationship to gender, race–ethnicity, and chronologic age. Rehabil Psychol 1998; 43: 282–296.

Charlifue S, Gerhart K . Community integration in spinal cord injury of long duration. NeuroRehabilitation 2004; 19: 91–101.

Charlifue SW, Weitzenkamp DA, Whiteneck GG . Longitudinal outcomes in spinal cord injury: aging, secondary conditions, and well-being. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1429–1434.

McColl MA, Arnold R, Charlifue S, Glass C, Savic G, Frankel H . Aging, spinal cord injury, and quality of life: structural relationships. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003; 84: 1137–1144.

Krause JS, Crewe NM . Chronologic age, time since injury, and time of measurement: effect on adjustment after sinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1991; 72: 91–100.

Krause JS, Sternberg M . Aging and adjustment after spinal cord injury: the roles of chronologic age, time since injury, and environmental change. Rehabil Psychol 1997; 42: 287–302.

Crewe NM, Krause JS . An eleven-year follow-up of adjustment to spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol 1991; 35: 205–210.

Krause JS, Crewe NM . Long term prediction of self-reported problems following spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1990; 28: 186–202.

Krause JS . Longitudinal changes in adjustment after spinal cord injury: a 15-year study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1992; 73: 564–568.

Krause JS . Aging and life adjustment after spinal cord injury: the impact of 30 or more years since injury. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 320–328.

Krause JS, Broderick LE . Community outcomes after spinal cord injury: comparisons as a function of gender and race/ethnicity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 355–362.

Krause JS, Kemp BJ, Coker JL . Depression after spinal cord injury: relationship with gender, race/ethnicity, aging and socioeconomic indicators. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81: 1099–1109.

Krause JS, Sternberg M, Maides J, Lottes S . Employment after spinal cord injury: differences related to geographic region, gender and race. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 615–624.

Krause JS . Community reintegration after SCI: relationship to gender and race. Topics Spinal Cord Injury Rehabil 1998; 4: 31–41.

Krause JS . Activity patterns after spinal cord injury: relationship to gender and race. Topics Spinal Cord Injury Rehabil 1998; 4: 31–41.

Krause JS, Anson CA . Adjustment after spinal cord injury: relationship to gender and race. Rehabil Psychol 1997; 42: 31–46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krause, J., Broderick, L. A 25-year longitudinal study of the natural course of aging after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 43, 349–356 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101726

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101726

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Longitudinal changes in employment, health, participation, and quality-of-life and the relationships with long-term survival after spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

Social participation as a mediator of the relationships of socioeconomic factors and longevity after traumatic spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Trends in nonroutine physician visits and hospitalizations: findings among five cohorts from the Spinal Cord Injury Longitudinal Aging Study

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Participation in activities and secondary health complications among persons aging with traumatic spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2017)

-

The natural course of spinal cord injury: changes over 40 years among those with exceptional survival

Spinal Cord (2017)