Abstract

Serotonin receptor changes have been associated with the pathophysiology and treatment of major depression. Only one other study has investigated serotonin receptor changes in older depressed patients. We used positron emission tomography (PET) and [18F]altanserin, a ligand with high affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor, to examine the relationship between 5-HT2A receptor density and depression. Depressed subjects (n=16), age>50 years, were recruited as part of a larger study. Older depressed subjects consisted of early-onset recurrent depression (EORD, n=11) and late-onset depression (LOD, n=5). An age-matched control group (n=9) was also recruited. All subjects were right-handed, nonsmokers and antidepressant-free. Regions of interest were determined on a summed MPRAGE scan transformed into Talairach space and coregistered with the PET images. Depressed subjects had less hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding than controls (p=0.05). No significant differences in receptor binding were found between EORD and LOD subjects. Depressed subjects not previously treated for depression (n=6) had less hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding (p=0.04) than previously treated subjects (n=10). It may be that prior medication treatment provides a compensatory upregulation of the 5-HT2A receptor.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The serotonin system has been the focus of a large literature implicating serotonin neurotransmitter disturbances in the pathophysiology of depression. Of the 14 different classes of serotonin receptors identified to date, the 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A receptors are the ones that have been most extensively investigated in depression. Using positron emission tomography (PET) and a radioligand with good sensitivity and specificity, human brain 5-HT2A receptors can be measured in vivo. [18F]altanserin has high affinity (Ki=0.13 nM) and selectivity for imaging 5-HT2A receptors (Lemaire et al, 1991), and has in vivo binding in rat brain comparable to in vitro mapping of 5-HT2A receptors (Biver et al, 1997a). It also has good in vivo test–retest reliability in humans (Smith et al, 1998) with an established literature in human brain mapping using PET (Biver et al, 1997b; Smith et al, 1998; Meltzer et al, 1999; Larisch et al, 2001).

Brain imaging studies of 5-HT2A receptor binding in depression have yielded conflicting results, both in terms of whether there are differences from controls and if so, where the differences are located. With the exception of one study (Meltzer et al, 1999), human imaging studies were conducted in young and mid-life subjects. Meyer et al (1999) found no significant differences between 14 young adult unmedicated depressed and controls subjects using [18F]setoperone to measure a large prefrontal region (Brodmann areas 9 and parts of 8, 10, 32, and 46). In a sample of seven young adult benzodiazepine-treated patients, Attar-Levy et al (1999) found significant decreases in frontal 5-HT2A receptors determined with [18F]setoperone but no differences in temporal, parietal, or occipital receptors. Using spiperone, Moresco et al (2000) found significant differences in 15 antidepressant-free depressed subjects in frontal, temporal, and occipital cortex but not in the anterior cingulate. Biver et al (1997b) found significant reduction in orbito-frontal and insular 5-HT2A receptors in eight depressed antidepressant-free subjects using [18F]altanserin, a ligand with virtually no affinity for dopamine. Also using altanserin, Larisch et al (2001) found significant reductions in frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital cortex in 12 subjects who were on antidepressants.

The only study (Meltzer et al, 1999) to examine 5-HT2A receptor binding in older depressed subjects (mean age 65 years) found no significant differences from controls in any of the brain regions examined. This study included 11 cortical areas and the striatum using [18F]altanserin in 11 depressed antidepressant-free subjects and matched controls. In a recent study (Mintun et al, 2004), we have found significant differences in hippocampal 5-HT2A receptors in depressed subjects compared with controls in a primarily mid-life sample spanning young to older subjects (mean age of 49.6 years). In the current study, we sought to characterize the differences in 5-HT2A receptor binding between older subjects with depression and controls, and to gather preliminary data on potential serotonin-binding differences in subgroups of older subjects—early-onset recurrent depression (EORD) and late-onset depression (LOD).

It has been hypothesized that LOD may have a different etiology, characterized by less family history of depression (Baron et al, 1981) and greater comorbid illness (Jacoby et al, 1981). Greater comorbidity has been hypothesized to result in a higher degree of neuroanatomical pathology, including increased white matter hyperintensities (Krishnan et al, 1997) and interruption in white matter tracts between basal ganglia and frontal cortex, potentially involving loss of cells with 5-HT2A receptors. We quantitatively evaluated 5-HT2A receptor binding using PET with [18F]altanserin in selected brain regions (Mintun et al, 2004) of antidepressant-free patients with depression compared with age-matched comparison subjects.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Older patients (n=16), age ⩾50 years, were included in this study from a larger sample of 46 depressed subjects (Mintun et al, 2004). They were recruited to the WUSM Depression and Neuroimaging Center from the community by advertisement and from referrals. In addition to age ⩾50 years, inclusion criteria were a current untreated episode of MDD by DSM-IV criteria, established in a structured clinical interview by a board certified psychiatrist (YIS), right-handedness, and nonsmoker. In addition, if the first depressive episode had occurred at age ⩾50 years, the patient was classified as LOD (n=5; F=3), whereas onset before age 50 years was classified as EORD (n=11, F=6). Subjects younger than 50 years were not included in the current study.

Nine subjects were included in a comparison group of seven female and two male subjects who were recruited primarily by advertisement. Depressed subjects and comparison subjects were evaluated by the Diagnostic Criteria for Genetic Studies (DIGS) criteria to exclude a history of any psychiatric illness other than depression and any psychiatric illness, respectively. All subjects were screened to exclude cognitive impairment by the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR=0) and to exclude acute physical illness by physical examination, medical records, and laboratory testing. Subjects were screened to determine cerebrovascular risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, and any history of transient ischemic attack, stroke, myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft, or angioplasty. Length of time since last use of antidepressants was determined. Our criteria were to include no subjects with a history of using any psychotropic medication within 4 weeks of recruitment or five half lives, whichever was greater. In two cases, however, because it was clinically important to begin therapy, we included patients who had only been off of nefazodone (1) and venlafaxine (1) for 2 weeks. In addition, no subjects were included who were being treated with potential CNS-active drugs. Thus, a large number of patients on antihypertensive therapy were excluded, for example, patients on propranolol or calcium channel blockers. No comparison subjects were included with a first-degree relative with affective illness.

All subjects were rated for depression symptom severity using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) (Hamilton, 1960). All subjects gave written informed consent after the procedures had been fully explained. The study was approved by the Human Studies Committee and Radioactive Drug Research Committee of Washington University School of Medicine.

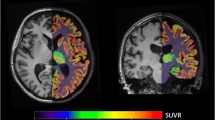

[18F]altanserin was prepared using modifications of previously reported methods (Tan et al, 1999; Lemaire et al, 1991; Sheline et al, 2002). Peripheral radiometabolites were determined using techniques adapted from radio-thin-layer chromatography methods previously developed for other PET radioligands (Moerlein et al, 1997). PET images were obtained using a Siemens 961HR PET scanner (Siemens/CTI, Inc., Knoxville, KY). Image processing and quantitative analysis of receptor binding using a four-compartment model kinetic analysis was performed as previously described (Mintun et al, 2004) to yield estimates of [18F]altanserin binding to 5-HT2A receptors, expressed as k3/k4 values.

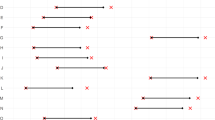

An MRI scan was obtained on a 1.5 T Vision system (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) using a magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence to generate anatomic images. Nine regions of interest (ROI) were created as previously described (Sheline et al, 2002): four limbic regions for hypothesis testing were hippocampus, subgenual anterior cingulate, pregenual anterior cingulate, and anterior medial gyrus rectus. Four comparison regions predicted not to have reduced 5-HT2A receptors were occipital cortex, dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex, lateral temporal cortex, and superior parietal cortex. The cerebellum was used to provide an area that is very low in 5-HT2A receptors (Pazos et al, 1987a) for use in compartmental modeling as described (Mintun et al, 2004). ROI were determined using a summed MPRAGE anatomic image, created in atlas coordinates, which had been created from all subjects in the study (see Figure 1). Anatomic boundaries were described by specific rules (Sheline et al, 2002) and ROIs were drawn in ANALYZE by the same research assistant for all ROIs, with consensus by YS and MM. In addition, for the hippocampus, volumetric determination was conducted using stereological estimation techniques as previously described (Sheline et al, 1999) and with the data previously reported (Mintun et al, 2004).

Representative regions of interest (ROI). Nine ROI were created as previously described (Sheline et al, 2002): four limbic regions for hypothesis testing were hippocampus, subgenual anterior cingulate, pregenual anterior cingulated, and anterior medial gyrus rectus. Five comparison regions were occipital cortex, dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex, lateral temporal cortex, superior parietal cortex, and cerebellum. ROI were determined using a summed MPRAGE anatomic image, created in atlas coordinates, which had been created from all subjects in the study.

The dependent variables were analyzed using orthogonal focused contrasts within the context of a one-way ANOVA. The first contrast compared the combination of EORD and LOD groups to controls. When this contrast was significant, a second contrast compared the EORD and LOD groups to each other. Effect sizes are expressed as Cohen's D.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of the 16 older depressed subjects (11 EORD and 5 LOD) and the 9 comparison subjects are presented in Table 1. The mean ages between the depressed (DEP) and NC groups were similar, although there was a trend for EORD individuals to be younger than LOD individuals. Years of education and gender did not significantly differ between DEP and NC groups or between EORD and LOD groups. Presence or absence of hypertension was compared between DEP and control subjects and between LOD and EORD subjects. As shown in Table 1, DEP subjects had significantly more hypertension than controls (χ2 p value=0.04), but they did not differ in hyperlipidemia. Similarly, EORD and LOD subjects were compared. While not differing in hypertension, LOD subjects had significantly greater incidence of hyperlipidemia than EORD (χ2 p-value=0.03). In the LOD group, one subject accounted for one case each of myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, angioplasty, and coronary artery bypass graft. None of the other subjects had these diagnoses and no subjects had a history of stroke, transient ischemic attacks, diabetes mellitus, or atrial fibrillation.

Hippocampal volumes were ascertained as described in the Participants and Methods section. Depressed and control subjects volumes, respectively, were 2126±388 vs 2122±268 (left), 2060±435 vs 2138±269 (right), and 4186±806 vs 4260±499 (total) (all p-values >0.50).

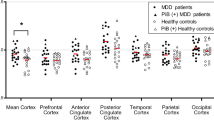

The k3/k4 values (Table 2) demonstrated a 39% hippocampal decrease in the depressed group compared to controls (see Figure 2). There were no gender effects on hippocampal k3/k4, however, the number of subjects was small. In our larger sample (Mintun et al, 2004), we examined the effect of gender on hippocampal k3/k4 and found no significant gender effect (p>0.20). Other regions also had numerically decreased receptor binding but the differences did not reach statistical significance. The nonspecific binding (expressed as k1/k2) of [18F]altanserin in the cerebellum was not significantly different between the depressed (mean±SD=0.57±0.14) and comparison subjects (mean±SD=0.53±0.14) (F=0.08, DF=1,22, p=0.78, ES=−0.29).

The individual hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding data points with standard deviation error bars and a mean receptor binding for each group are shown. On the left, the data are plotted for the controls (blue) and the late life depressed (LLD) group separated into early-onset recurrent depression—EORD (orange) and late-onset depression—LOD (green). On the right, the same LLD data are plotted separated into groups of patients never previously medicated for depression (yellow) and for patients with prior treatment (red).

DEP patients were subdivided into those with late onset (LOD) vs those with early onset (EORD) and in a multiple regression analysis with age, the k3/k4 binding was compared in the hippocampus, the only region which was significantly different between DEP and comparison subjects. There were no significant differences in hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding; however, the patients with late onset depression had numerically smaller values (mean of 0.30 vs 0.45).

Additionally, treatment history was ascertained and those with prior antidepressant treatment (n=10) vs those with no prior antidepressant treatment (n=6) were compared using unpaired t-tests. There were statistically significant differences in hippocampal k3/k4 (t=1.9, df=14, p=0.04), an effect size of 0.81 representing a 44% decrease in the group with no prior treatment. These differences are plotted in Figure 2. To rule out a relationship between time off antidepressants and hippocampal k3/k4 in the depressed subjects previously treated with antidepressants, a linear regression was conducted, which was not significant (p>0.50). A summary of the times off of antidepressant medication was as follows: of the 16 depressed patients, six were medication naïve. Ten had been previously treated, with number of weeks off antidepressants as follows: two were off for 2 weeks (nefazodone and venlafaxine), two were off antidepressants for 8 weeks each, two were off for 12 weeks each, four were off for ⩾52 weeks.

To explore whether the data suggested a relationship between depression severity and 5-HT2A receptor binding, correlations were conducted between the HAMD scores obtained at the time of the PET scan and the patients' regional k3/k4 values. None of the regions of interest demonstrated a significant correlation (p>0.05) between the HAMD scores and k3/k4 value.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated a significant decrease in hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding in older patients with depression compared with controls. The difference was large in absolute terms (39%), similar to our previously reported 30% decrease in hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding in a younger sample (Mintun et al, 2004). Other brain regions also had minimal decreases in 5-HT2A receptors, 0.6% on average, none of which reached significance (all p-values >0.20).

Our finding of decreased hippocampal 5-HT2A receptors in older patients with depression must be examined critically given the potential for involvement of confounding factors. An important issue is the specificity of the 5-HT2A receptor radioligand. Typically, this class of tracers has binding to both dopamine-2 and 5-HT2C receptors. In regards to the 5-HT2C receptor, the affinity of altanserin for 5-HT2A receptor (Ki=0.3 nM) relative to 5-HT2C receptors (Ki=6 nM; Tan et al, 1999) is 20-fold higher. In the hippocampus, the concentrations of 5-HT2A receptors and 5-HT2C receptors are approximately equal as measured by ketanserin (Pazos et al, 1987a) and [3H]mesulergin (Pazos et al, 1987b), respectively. These reports showed values for 5-HT2A receptors ranging from 118 to 185 fmol/mg protein and values for 5-HT2C receptors ranging from 40 to 140 fmol/mg protein. Interestingly, there is much more disparity in the cortex in which 5-HT2A receptors outnumber 5-HT2C receptors by approximately four-fold. Given the 20-fold difference in affinity and the presence of only equal numbers of 5-HT2C receptors, there should be only a small percentage of the [18F]altanserin uptake being associated with the 5-HT2C receptor. In the case of dopamine-2 receptors, there is both an extremely low concentration in hippocampus (Kesser et al, 1993) as well as a low affinity (Ki=62 nM; Lemaire et al, 1991) essentially removing the possibility of significant binding to this receptor.

Another issue is patients on current or recent antidepressants. All patients in this study were studied off any antidepressant medications, as these drugs could theoretically alter 5-HT2A receptors (Charney et al, 1981; Leysen, 1992; Meyer et al, 2001; Yatham et al, 2001; Zanardi et al, 2001). Further, prior treatment with antidepressant medications potentially could cause ongoing alteration in 5-HT2A receptors. We found no relationship between duration of time off of antidepressant medication and hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding. In addition, medication-naïve subjects actually had a larger difference in hippocampal 5-HT2A receptors from controls, indicating that previous antidepressant therapy cannot explain the decreased number of receptors, an observation we also made recently in a larger sample (Mintun et al, 2004).

Hippocampal volume decreases have been reported in patients with MDD (Sheline et al, 1999; Bremner et al, 2000; Bell-McGinty et al, 2002; MacQueen et al, 2003), but significant differences were not found in the current investigation. Owing to limited resolution and partial volume effects, PET could theoretically underestimate 5-HT2A hippocampal binding in subjects with a large degree of gray matter loss. However, the decrease in 5-HT2A hippocampal binding is of greater magnitude than the nonsignificant hippocampal volume loss in this sample (39 vs 2%) and could indicate that while both conditions may coexist, the 5-HT2A binding changes are unlikely to be explained by simple generalized gray matter loss.

As previously discussed (Mintun et al, 2004), the specific methodology for conversion of the PET activity measures into 5-HT2A receptor estimates should also be considered. This work utilized a quantitative four-compartment model with correction for labeled metabolites to calculate 5-HT2A receptor k3/k4 and given other work validating this model it is unlikely that the lower hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor values seen in late life MDD could be a result of differences in nonspecific binding or the specific method used for analyzing the tracer curves.

Consistent with the literature, our results show a nonsignificant decrease in 5-HT2A receptors throughout multiple brain regions. Other reports also primarily show nonsignificant differences in 5-HT2A receptor ligand binding between controls and depressed patients (Attar-Levy et al, 1999; Meyer et al, 1999; Meltzer et al, 1999). Some studies have found decreased 5-HT2A receptor binding in depressed patients more diffusely (Larisch et al, 2001; Yatham et al, 2000; Moresco et al, 2000). Biver et al (1997b) found decreased 5-HT2A receptor binding in a single region of the frontal cortex. Methods of analysis and selectivity of radiotracers used varied widely across these reports and may be a source of the variability of the results. None, however, has identified significantly decreased hippocampal receptor binding and only Meltzer et al (1999) specifically commented on the hippocampal region. Using hippocampal/amygdaloid ROIs and [18F]altanserin PET scanning in 11 late-life depressed patients and age-matched controls they found no difference between depressed and control groups (Meltzer et al, 1999). One difference in their methods was that their region of interest (ROI) was a combined hippocampus/amygdala region, perhaps diluting any differences in hippocampal binding. Other differences were the slightly smaller sample size in the Meltzer study (11 depressed subjects vs 16 depressed subjects in our study) and older age of that sample. Since there is a large age-related decrease in 5HT2A receptors (Sheline et al, 2002), the absolute difference in hippocampal binding between depressed and control subjects would be decreased in an older sample.

In neuropathological studies, two reported no significant differences in hippocampal 5HT2A receptors (Crow et al, 1984; Lowther et al, 1994). Rosel et al (1998, 2000), however, found a 40% decrease in hippocampal 5-HT2A-binding sites in antidepressant-free suicide victims. Another post-mortem study (Cheetham et al, 1988) identified a 23% decrease in hippocampal 5-HT2A-binding sites in a study of antidepressant-free suicide victims. These post-mortem suicide studies provides qualified support for our in vivo data finding decreases in the hippocampal 5-HT2A-receptor density in patients with LLD.

Given that differences between EORD and LOD have been reported, we compared clinical and 5-HT2A receptor binding between subjects with LOD and EORD. We did not find a difference between late-onset and early-onset late life depressed subjects in hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding, although our sample lacked sufficient power to say that there was no difference. A post hoc regression analysis found no relation between age of onset and hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding, when taking into account the current age.

The significantly (44%) lower hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding in subjects without prior antidepressant compared to those with prior antidepressant treatment is intriguing. It is important to consider data on the potential functional impact of decreased 5-HT2A receptors in the hippocampus. There is evidence for stress (Duman et al, 1997) and depression (Shimizu et al, 2003) effects on an important factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is involved in maintaining neuronal viability. Several neurotransmitter systems including monoamine systems are influenced by stress and could regulate the expression of BDNF (Chaouloff, 1993; Kuchel, 1991). Activation of hippocampal 5-HT2A receptors decreases levels of BDNF mRNA in the hippocampus in a manner similar to that observed after stress (Vaidya et al, 1997). Thus, greater numbers of 5-HT2A receptors during stress could contribute to stress-induced hippocampal atrophy. Duman and co-workers (Duman et al, 1997; Vaidya and Duman, 1999) have proposed that decreased hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding can be a compensatory mechanism in the stress response. Whereas 5-HT2A receptors in other cortical regions are involved in increasing BDNF during stress, hippocampal 5-HT2A receptors appear to have a key role in producing a decrease in BDNF during stress. This decrease in BDNF could potentially contribute to stress-induced atrophy and death of vulnerable neurons (Vaidya and Duman, 1999). Therefore, hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor decreases that occur in depression may be part of an adaptation to chronic stress via homeostatic reduction or autoregulation of receptors. Intriguingly, we found that patients previously treated with antidepressants had partially normalized 5-HT2A receptor levels compared with never-treated subjects, in support of this hypothesis.

In summary, we present preliminary data on hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor-binding differences in late life depression, finding decreased binding in older depressed patients compared with controls and no significant differences between LOD and EORD. We report a significant decrease in subjects never previously treated for depression compared with those with prior depression treatment. We have found no differences between DEP and control 5-HT2A receptor binding in any other brain regions; however, given our small sample size this cannot be considered definitive.

References

Attar-Levy D, Martinot JL, Blin J, Dao-Castellana MH, Crouzel C, Mazoyer B et al (1999). The cortical serotonin2 receptors studied with positron-emission tomography and [18F]-setoperone during depressive illness and antidepressant treatment with clomipramine. Biol Psychiatry 45: 180–186.

Baron M, Mendlewicz J, Klotz J (1981). Age-of-onset and genetic transmission in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 64: 373–380.

Bell-McGinty S, Butters MA, Meltzer CC, Greer PJ, Reynolds III CF, Becker JT (2002). Brain morphometric abnormalities in geriatric depression: long-term neurobiological effects of illness duration. Am J Psychiatry 159: 1424–1427.

Biver F, Lotstra F, Monclus M, Dethy S, Damhaut P, Wikler D et al (1997a). In vivo binding of [18F]altanserin to rat brain 5HT2 receptors: a film and electronic autoradiographic study. Nucl Med Biol 24: 357–360.

Biver F, Wikler D, Lotstra F, Damhaut P, Goldman S, Mendlewicz J (1997b). Serotonin 5-HT2 receptor imaging in major depression: focal changes in orbito-insular cortex. Br J Psychiatry 171: 444–448.

Bremner JD, Narayan M, Anderson ER, Staib LH, Miller HL, Charney DS (2000). Hippocampal volume reduction in major depression. Am J Psychiatry 157: 115–118.

Chaouloff F (1993). Physiopharmacological interactions between stress hormones and central serotonergic systems. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 18: 1–32.

Charney DS, Menkes DB, Heninger GR (1981). Receptor sensitivity and the mechanism of action of antidepressant treatment. Implications for the etiology and therapy of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 38: 1160–1180.

Cheetham SC, Crompton MR, Katona CL, Horton RW (1988). Brain 5-HT2 receptor binding sites in depressed suicide victims. Brain Res 443: 272–280.

Crow TJ, Cross AJ, Cooper SJ, Deakin JF, Ferrier IN, Johnson JA et al (1984). Neurotransmitter receptors and monoamine metabolites in the brains of patients with Alzheimer-type dementia and depression, and suicides. Neuropharmacology 23: 1561–1569.

Duman RS, Heninger GR, Nestler EJ (1997). A molecular and cellular theory of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54: 597–606.

Hamilton M (1960). A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 23: 56–62.

Jacoby RJ, Levy R, Bird JM (1981). Computed tomography and the outcome of affective disorder: a follow-up study of elderly patients. Br J Psychiatry 139: 288–292.

Kesser RM, Whetsell WO, Ansari MS, Votaw JR, de Paulis T, Clanton JA et al (1993). Identification of extrastriatal dopamine D2 receptors in post mortem human brain with [125I]epidepride. Brain Res 609: 237–243.

Krishnan K, Hays J, Blazer D (1997). MRI-Defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry 154: 497–501.

Kuchel O (1991). Stress and catecholamines. Methods Achiev Exp Pathol 14: 80–103.

Larisch R, Klimke A, Mayoral F, Hamacher K, Herzog HR, Vosberg H et al (2001). Disturbance of serotonin 5HT2 receptors in remitted patients suffering from hereditary depressive disorder. Nuklearmedizin 40: 129–134.

Lemaire C, Cantineau R, Guillaume M, Plenevaux A, Christiaens L (1991). Fluorine-18-altanserin: a radioligand for the study of serotonin receptors with PET: radiolabeling and in vivo biologic behavior in rats. J Nucl Med 32: 2266–2272.

Leysen JE (1992). 5HT2A-receptors: location, pharmacological, pathological and physiological role. In: Langer SZ, Brunello N, Racagni G, Mendlewicz J (eds). Serotonin Receptor Subtypes: Pharmacological Significance and Clinical Implications. Basel: Karger. pp 31–43.

Lowther S, De Paermentier F, Crompton MR, Katona CL, Horton RW (1994). Brain 5-HT2 receptors in suicide victims: violence of death, depression and effects of antidepressant treatment. Brain Res 642: 281–289.

MacQueen GM, Campbell S, McEwen BS, Macdonald K, Amano S, Joffe RT et al (2003). Course of illness, hippocampal function, and hippocampal volume in major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 1387–1392.

Meltzer CC, Price JC, Mathis CA, Greer PJ, Cantwell MN, Houck PR et al (1999). PET imaging of serotonin type 2A receptors in late-life neuropsychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry 156: 1871–1878.

Meyer JH, Kapur S, Eisfeld B, Brown GM, Houle S, DaSilva J et al (2001). The effect of paroxetine on 5-HT(2A) receptors in depression: an [(18)F]setoperone PET imaging study. Am J Psychiatry 158: 78–85.

Meyer JH, Kapur S, Houle S, DaSilva J, Owczarek B, Brown GM et al (1999). Prefrontal cortex 5-HT2 receptors in depression: an [18F]setoperone PET imaging study. Am J Psychiatry 156: 1029–1034.

Mintun MA, Sheline YI, Moerlein SM, Vlassenko AG, Huang Y, Snyder AZ (2004). Decreased hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding in major depressive disorder: in vivo measurement with [18F] altanserin positron emission tomography. Biol Psychiatry 55: 217–224.

Moerlein SM, Perlmutter JS, Cutler PD, Welch MJ (1997). Radiation dosimetry of [18F] (N-methyl)benperidol as determined by whole-body PET imaging of primates. Nucl Med Biol 24: 311–318.

Moresco RM, Colombo C, Fazio F, Bonfanti A, Lucignani G, Messa C et al (2000). Effects of fluvoxamine treatment on the in vivo binding of [F-18]FESP in drug naive depressed patients: a PET study. Neuroimage 12: 452–465.

Pazos A, Probst A, Palacios JM (1987a). Serotonin receptors in the human brain—IV. Autoradiographic mapping of serotonin-2 receptors. Neuroscience 21: 123–139.

Pazos A, Probst A, Palacios JM (1987b). Serotonin receptors in the human brain—III. Autoradiographic mapping of serotonin-1 receptors. Neuroscience 21: 97–122.

Rosel P, Arranz B, San L, Vallejo J, Crespo JM, Urretavizcaya M et al (2000). Altered 5-HT(2A) binding sites and second messenger inositol trisphosphate (IP(3)) levels in hippocampus but not in frontal cortex from depressed suicide victims. Psychiatry Res 99: 173–181.

Rosel P, Arranz B, Vallejo J, Oros M, Crespo JM, Menchon JM et al (1998). Variations in [3H]imipramine and 5-HT2A but not [3H]paroxetine binding sites in suicide brains. Psychiatry Res 82: 161–170.

Sheline YI, Mintun MA, Moerlein SM, Snyder AZ (2002). Greater loss of 5-HT(2A) receptors in midlife than in late life. Am J Psychiatry 159: 430–435.

Sheline YI, Sanghavi M, Mintun MA, Gado MH (1999). Depression duration but not age predicts hippocampal volume loss in medically healthy women with recurrent major depression. J Neurosci 19: 5034–5043.

Shimizu E, Hashimoto K, Okamura N, Koike K, Komatsu N, Kumakiri C et al (2003). Alterations of serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in depressed patients with or without antidepressants. Biol Psychiatry 54: 70–75.

Smith GS, Price JC, Lopresti BJ, Huang Y, Simpson N, Holt D et al (1998). Test–retest variability of serotonin 5-HT2A receptor binding measured with positron emission tomography and [18F]altanserin in the human brain. Synapse 30: 380–392.

Tan PZ, Baldwin RM, van Dyck CH, Al Tikriti M, Roth B, Khan N et al (1999). Characterization of radioactive metabolites of 5-HT2A receptor PET ligand [18F]altanserin in human and rodent. Nucl Med Biol 26: 601–608.

Vaidya VA, Duman RS (1999). Role of 5-HT2A receptors in down-regulation of BDNF by stress. Neurosci Lett 287: 1–4.

Vaidya VA, Marek GJ, Aghajanian GK, Duman RS (1997). 5-HT2A receptor-mediated regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in the hippocampus and the neocortex. J Neurosci 17: 2785–2795.

Yatham LN, Liddle PF, Shiah IS, Lam RW, Adam MJ, Zis AP et al (2001). Effects of rapid tryptophan depletion on brain 5-HT(2) receptors: a PET study. Br J Psychiatry 178: 448–453.

Yatham LN, Liddle PF, Shiah IS, Scarrow G, Lam RW, Adam MJ (2000). Brain serotonin 2 receptors in major depression: a positron emission tomography study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57: 850–858.

Zanardi R, Artigas F, Moresco R, Colombo C, Messa C, Gobbo C et al (2001). Increased 5-hydroxytryptamine-2 receptor binding in the frontal cortex of depressed patients responding to paroxetine treatment: a positron emission tomography scan study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 21: 53–58.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH) with grants K24MH6542, MH58444, MH54731, and RR00036.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sheline, Y., Mintun, M., Barch, D. et al. Decreased Hippocampal 5-HT2A Receptor Binding in Older Depressed Patients Using [18F]Altanserin Positron Emission Tomography. Neuropsychopharmacol 29, 2235–2241 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300555

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300555

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The human raphe-hippocampal tract and affective sensitivity: a probabilistic tractography study

Brain Imaging and Behavior (2022)

-

Mapping the physiological and molecular markers of stress and SSRI antidepressant treatment in S100a10 corticostriatal neurons

Molecular Psychiatry (2020)

-

Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of low dose lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in healthy older volunteers

Psychopharmacology (2020)

-

New Psychoactive Substances (NPS), Psychedelic Experiences and Dissociation: Clinical and Clinical Pharmacological Issues

Current Addiction Reports (2019)

-

PET Imaging of Serotoninergic Neurotransmission with [11C]DASB and [18F]altanserin after Focal Cerebral Ischemia in Rats

Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism (2013)