Abstract

Modification of surface and bulk properties of solids by irradiation with ion beams is a widely used technique with many applications in material science. In this study, we show that nano-hillocks on CaF2 crystal surfaces can be formed by individual impact of medium energy (3 and 5 MeV) highly charged ions (Xe22+ to Xe30+) as well as swift (kinetic energies between 12 and 58 MeV) heavy xenon ions. For very slow highly charged ions the appearance of hillocks is known to be linked to a threshold in potential energy (Ep) while for swift heavy ions a minimum electronic energy loss per unit length (Se) is necessary. With our results we bridge the gap between these two extreme cases and demonstrate, that with increasing energy deposition via Se the Ep-threshold for hillock production can be lowered substantially. Surprisingly, both mechanisms of energy deposition in the target surface seem to contribute in an additive way, which can be visualized in a phase diagram. We show that the inelastic thermal spike model, originally developed to describe such material modifications for swift heavy ions, can be extended to the case where both kinetic and potential energies are deposited into the surface.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interaction of energetic ions with solid surfaces has been a center of attention in material science over the last century, not least because profound knowledge of the underlying physical mechanisms has contributed greatly to technological applications. A number of analytical methods, e.g. Rutherford backscattering spectrometry (RBS) or secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS), could not have been developed without this continuous research. Energy deposition by energetic ions in matter also has important applications in other fields like astrobiology (synthesis of amino acids), nuclear fusion (wall erosion in fusion experiments), space exploration (radiation hardness of electronic devices) and others.

Great interest has been drawn by the use of ions as possible tools for lithographic modifications or “nanostructuring” of surfaces. Due to technical restrictions, earlier studies in the field of nanostructuring were conducted with ions at relatively high kinetic energies and low ion charge states, where interaction processes are governed primarily by the ion mass and kinetic energy. Investigations have shown that swift heavy ions (SHI) with kinetic energies in the MeV–GeV range can induce severe structural modifications at the surface1 and in the bulk2. These modifications not only include the formation of surface nanostructures, such as protrusions3 or craters4, but also phase transitions by swift heavy ions (e.g., from crystalline to amorphous5 or crystalline to crystalline6) and the creation of latent tracks, which can reach several tens of micrometers deep into the solid7.

The interaction of individual slow highly charged ions (HCI) in the keV energy regime with solid surfaces can also induce surface modifications on a nanometric scale8, which appear as either hillocks, pits or craters9,10,11,12,13,14. These modifications result from the deposition of potential energy carried by slow HCI (i.e. the sum of the binding energies of all missing electrons) into the target electronic system. Within a few femtoseconds (fs), electrons from the target are captured into highly excited states of the projectile15. The energy (several keV/nm3) deposited into the electron target by emission of fast electrons is not precisely known16. Similarly, hillocks created by SHI with impact energies of some hundreds of MeV appear at the surface for an energy density of typically 10 keV/nm3. These energies provided by ion-electron collisions in the fs time range17,18,19, have been measured20,21,22. In this case, fast electrons are created by direct collisions with the ions and their energy distribution can be approximated by an analytical formula proposed by Waligorski et al.23 that fits the results of Monte Carlo calculations24. We conclude that independent of the energy deposition channel to the electrons, i.e. potential energy (Ep) deposition by HCI or electronic energy loss per length unit (Se) by SHI, the target electronic system is highly excited in a first step by the generation of fast electrons. The electron energy relaxation towards the atoms occurs in a second step, which suggests that the material modifications induced at the surface have a common underlying mechanism, as pointed out by Aumayr et al.8. Interpreting their results for CaF2, El-Said et al.9 were the first to put forward that hillock formation by slow HCI may be described by the inelastic thermal spike model25 originally developed to predict material modifications induced by SHI. Along the lines of this model, the sharp threshold of potential energy for hillock formation by slow HCI has been linked to a solid-liquid phase transition (nano-melting)8,9.

In this paper we firstly establish the so far missing quantitative link between HCI and SHI induced nano-hillocks. By bombarding CaF2 single crystal surfaces with medium energy (3 and 5 MeV) multiply charged xenon ions which deposit a considerable amount of both potential and kinetic energy into the surface, we can demonstrate that both mechanisms of energy deposition into the target surface are found to contribute in an additive way. Based on this relation, the inelastic thermal spike model, originally developed to describe such material modifications for swift heavy ions, can be extended to nanostructure formation by highly charged ions.

Results

Hillock formation and surface roughening by medium energy HCI

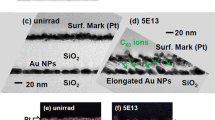

Fig. 1 shows AFM images of samples irradiated by 5 MeV Xe21+ (a), Xe22+ (b) and Xe30+ (c) ions. For Xe21+ (Fig. 1a), no hillocks are observable and the irradiated sample stays flat with a mean roughness of 0.07 nm. The same is true for surfaces irradiated by ions in lower charge states (Xe20+, Xe19+). However, nano-hillocks clearly appear on surfaces after irradiation by Xe22+ (Fig. 1b), Xe26+ and Xe30+. For these cases, the number of hillocks per area corresponds well to the fluence of incident ions within the experimental error. Samples irradiated by 3 MeV Xe25+ ions (and ions in lower charge states) do not exhibit hillock formation, while for Xe26+, hillocks appear clearly but with the number of hillocks reduced to 1.5% of the incoming ion fluence. When using 3 MeV Xe30+ ions as projectiles, hillocks are clearly visible and their number is equal to the ion fluence.

CaF2 surfaces irradiated by 5 MeV Xe ions with a fluence of 500 ions/μm2.

The AFM images show an area of 1 × 1 μm2. A surface irradiated by (a) Xe21+with no hillocks visible, (b) Xe22+ with ~520 hillocks, (c) Xe30+ with ~410 hillocks. (d) presents the evolution of the surface roughness versus charge state for samples before and after irradiation with 5, 3 and 0.54 MeV Xe ions. The lines are there to guide the eye.

Fig. 1d shows the roughness of the irradiated samples, as calculated by the Gwyddion code26, plotted against the charge state of the Xe ions for different kinetic energies (3 and 5 MeV, plus one irradiation performed at 0.54 MeV). This illustrates a surprisingly sharp but impact energy dependent transition from flat to nanostructured CaF2 surfaces. The red dotted line which is just a link between Xe26+ and Xe30+ for 3 MeV irradiation is to guide the eye. Right at the threshold (Xe22+ for 5 MeV and Xe26+ for 3 MeV), the surface roughness increases significantly to values 4–10 times larger than the non-irradiated sample. Summing up the results it can be said that for Xe ions of 5 MeV, the threshold for nanostructuring lies between charge states 21+ and 22+, which corresponds to a potential energy of Ep5 ≈ 5.5 keV27. For lower kinetic energies of 3 MeV, the threshold is given by Xe25+ and Xe26+ or a potential energy of Ep3 ≈ 8.5 keV27. Both threshold values of Ep in this energy regime are considerably smaller than the ones in the keV regime as reported by El-Said et al.9 (between Xe27+ and Xe28+, corresponding to Ep0 ≈ 11.2 keV).

With increasing kinetic energy, nuclear and electronic energy loss per unit length of the projectile ion evolve differently. For energies between 0.0049 and 5 MeV, the nuclear energy loss is nearly constant, varying only from 1.15 keV/nm to 1 keV/nm respectively25. Such a 15% decrease of the nuclear energy loss within increasing kinetic energy cannot account for the observed decrease of the Ep threshold by 50% from 11.29 to 5.5 keV. But in the same energy range, Se increases considerably20,21. Since the electronic system of the target is excited by Se, independent of whether the energy is supplied by SHI or HCI, we conclude that a decrease of the Ep threshold has to be counter-balanced by an increased energy deposition via Se.

Hillock formation by SHI and the velocity effect

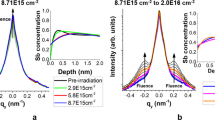

To determine the Se threshold for hillock creation by SHI, targets of CaF2 were irradiated with some tens of MeV of Xe ions delivered by the IRRSUD beam line of the GANIL facility28. Al foil degraders were used to reduce the kinetic energy of the initial 92 MeV Xe ion beam to values ranging between 12 and 58 MeV. The fluences applied were 5 × 109 Xe/cm2 and 1.5 × 1010 Xe/cm2. Using AFM in tapping mode19, the surface of each sample was analyzed after irradiation to extract the number of hillocks per cm2. The efficiency for hillock production (number density of hillocks divided by incident ion fluence) was deduced for irradiations at two fluences. Their mean values versus Se are plotted in Fig. 2. The Se values were calculated using the CasP code21 since its predictions of Se values are more realistic as compared to the ones by SRIM25 in the low MeV energy regime.

By extrapolation to zero efficiency, a linear fit, as previously done like in the GeV energy regime19, was applied to the three points at Se = 3.6, 5.9 and 9.5 keV/nm, leading to Se threshold of Set = 2.75 ± 0.40 keV/nm. This threshold value is by a factor of ~2 smaller than the Se threshold (~5 keV/nm) previously reported for SHI in the GeV regime29. Such a difference in the Se threshold can in principle result from the so-called “velocity effect”30: For SHI impact on a surface with different kinetic energies but with the same Se value, the energy deposited into the electronic system at lower ion velocity is transferred to the lattice atoms more efficiently than at higher energies. From our results we infer that CaF2 is sensitive to the velocity effect31 (as questioned by Szenes32).

In Fig. 3 we have summarized the results of our investigations in a “phase diagram” with Se and Ep as state variables. Cases where hillocks have been found after irradiation are displayed by full symbols (region B), while open symbols represent irradiations where the CaF2 surface stayed flat and showed no effect of the irradiation (region A). Additional data from slow HCI impact9 have been included in this plot. The Se values (~0.01 keV/nm for 3 keV, 0.72 keV/nm for 3 MeV and 1.46 keV/nm for 5 MeV Xe ions) were calculated with the CasP code21. The SHI threshold Set of 2.75 keV/nm (semi-black square in Fig. 3) for hillock formation is also given in the phase diagram, assuming a potential threshold of 0.62 keV corresponding to the expected equilibrium charge state of the Xe at 9 MeV21. The borderline between region A (no hillocks) and region B (hillocks) in the Se–Ep diagram (Fig. 3) is a linear fit of the Ep thresholds and the negative slope points out an additive contribution of Se and Ep to nano-hillock formation on the surface of CaF2. A decrease of Ep, transferred to the target clearly can be compensated by an increase of Se and vice versa. The extrapolation of this line to Ep = 0 gives Se0 of 2.75 ± 0.40 keV/nm (semi-black square in Fig. 3) is in agreement with the Set as deduced from SHI experiments.

Phase diagram of hillock formation on CaF2 irradiated by Xe ions with electronic energy loss and potential energy as state variables.

The corresponding kinetic energies and Xe charge states are given on the opposite axes, respectively. Open symbols represent cases where no hillocks have been found (region A), while full symbols mean the appearance of hillocks (region B). The blue diamonds are previous results9. The red circles stand for the present experiments. The semi-black square is the Se threshold deduced from SHI irradiations.

Data analysis: link between HCI and SHI at the thresholds of hillock formation

The additivity between Se and Ep derived from Fig. 3 can be expressed in a quantitative formula taking into account that only a fraction F33 of Ep is deposited in a depth d near the surface32.

F can either be derived from calorimetric measurements34 or by measuring the energy carried away by emitted electrons33. From our results (equ. 1), a ratio of the depth d in nanometer to the fraction F can be derived for CaF2 in beam energy range between 0.004 and 9 MeV:

where Ep0 is the potential threshold at Se = 0 and Se0 (≅ Set) the electronic energy loss for Ep = 0.

Inelastic thermal spike (i-TS) description

In the following we present an extension of the inelastic thermal spike (i-TS) model35, originally developed to describe material modifications induced by Se delivered by SHI, to medium and low energy HCI, where potential energy is deposited. As a central assumption, the threshold for hillock formation is linked to a solid-liquid phase transition (nano-melting)8,9 inside the target material.

i-TS model simulation for SHI

The original i-TS model describes a transient thermal process based on heat transport equations that govern the heat diffusion in time and space (radial distance from the ion path) in the electronic and atomic subsystem and their coupling by the electron-phonon constant g. For SHI the two equations are solved numerically in cylindrical geometry. The initial energy distribution of the electrons is derived from Monte Carlo calculations and implemented as an analytical formula23. The electron-phonon coupling constant g is linked to the electron-phonon mean free path λ35 that defines the mean length of energy diffusion of the electrons before its transfer to the atoms. The model was successfully applied for SHI in the GeV energy regime for several solids, independent of whether they are metals or insulators25 and references therein and directly applied to CaF229 with λ equal to 3.8 nmFig. 13a in 25. It is assumed that tracks and hillocks appear, if an energy of Em = 0.58 eV/atom, which is necessary to melt the material, is surpassed. Such calculated Se threshold for material modification is predicted by the i-TS model to be 5 keV/nm in the GeV regime in close agreement with experiments29. Applying the i–TS model to heavy ions in the MeV range30 (beam energy of 0.08 MeV/u, leading to an initial energy transfer to the electrons of the target in a cylinder radius of 1 nm23), a lower threshold of 2.6 ± 0.4 keV/nm is calculated for hillock formation, which is in excellent agreement with our experimental results presented in Fig. 2. The “theoretical” error of 0.4 keV/nm basically reflects the uncertainties in the initial energy distribution of the electrons.

Extension of the i-TS model for HCI - a 3D development

In order to take into account that the energy transferred to the electrons by Ep and Se is not constant along the ion path, the 3D i-TS model developed for metallic materials36 has been adapted for insulators, following the assumptions made for the electron subsystem as described in the previous section35. Moreover it is presumed that the electron-phonon mean free path (λ = 3.8 nm) is the one previously used for the description of the track induced by SHI. It is also assumed that a fraction (F) of Ep is homogeneously deposited into a cylindrical volume below the surface, which is characterized by a depth (d) and a radius (Rp). These assumptions are used to simplify the first application of the numerical solution of the i-TS model to describe the threshold of hillock formation by HCI. Moreover, in a layer of depth d below the surface, Se and F*Ep are deposited additively, while for larger depth Se is the only source of energy. The radial distribution of the potential energy has been estimated by Lemell et al.16, showing that the most efficiently interacting electrons are the ones with energies lower than 400 eV. These electrons are confined in a cylinder radius Rp between 0.5 and 2 nm. We can see from this that in order to perform the calculations, it is necessary to estimate d, Rp and F.

Several calculations were made to investigate the influence of Rp and d on the determination of the radius of the molten phase (Rm) at the surface and on the melting depth (dm) for a Xe ion energy of 5 MeV (Se = 1.4 keV/nm), see Table 1 and Fig. 4. For the same d value (3 nm) and the same deposited potential energy (F*Ep = 8.2 keV), an increase of Rp from 0.6 to 1.6 nm causes a 10% and 20% decrease of Rm and dm, respectively (see Fig. 4a–c). Comparing Fig.4b and 4d for the same F*Ep (8.2 keV) and Rp (1 nm) values, a decrease of the depth from 3 to 1 nm induces a decrease of Rm by 4% and dm by 20%, respectively. The small variation of Rm and dm results from the smearing out of the energy transferred to the electron subsystem of the target by the electron-electron interaction prior its transfer to the atoms due to the fact that Rp and d are smaller than the electron-phonon mean free path value.

Effect of different values of Rp and d of the cylinder (dashed blue rectangle) where the energy is transferred to the electrons compared to the calculated volume of the molten matter (the red line characterizes the evolution of the melting depth versus the melting radius).

The irradiation parameters are Xe ions with 5 MeV, leading to Se = 1.4 keV/nm and a deposited energy of F*Ep = 8.2 keV.

We will now use the i-TS model to describe the threshold of hillock appearance (Fig. 3) taking into account that the ratio d/F is constant in the range of potential energy and electronic energy loss investigated here. Fig. 5a presents the resulting maximum energy Ea transferred to a target atom for 3 MeV Xe ion impact on CaF2 versus the deposited Ep in different depths. The choice of d values was done according to the predictions of Lemell et al.16 and to the measurement of non-equilibrium energy loss37 in CaF2. The deposited potential energies needed to melt CaF2 are deduced when Ea reaches Em (0.58 eV/at) and are equal to 3.1, 4.1, 5.3 and 6.9 keV for the different depths (1, 2, 3 and 4 nm respectively). The respective values of the d/F ratio divided by the corresponding potential energy threshold of 8.5 keV, are 2.8, 4.1, 4.7 and 4.9 nm. These calculations are repeated for the experiment presented here (Xe ions at 5 MeV) and 0.004 MeV (slow HCI case9). The hereby obtained values of d/F are plotted in Fig. 5b against the experimentally measured Ep thresholds (5.5, 8.5 and 11.2 keV) with d as the parameter and are fitted linearly. Using the experimental value of d/F = 4.1 nm, the depths of interaction are 1.7, 2.0 and 2.3 nm, leading to F = 0.41, 0.49 and 0.56 for Ep = 5.5, 8.5 and 11.2 keV respectively. It can be seen that the depth of interaction and the fraction of deposited potential energy increase with Ep within the i-TS model. Comparing this data to the values predicted by Lemell16, d is in the same range of depth but F is larger.

(a) Maximum energy deposited on the atoms (eV/atom) calculated with the i-TS model for Xe ions at 3 MeV versus the deposited potential energy (F*Ep). The energy per atom at F*Ep = 0 corresponds to the electronic energy loss for Xe ions at 3 MeV. The deposited potential energy is given by a different cylinder volume with a radius of 1 nm for four different values of the depth (d = 1, 2, 3 and 4 nm). The dotted horizontal line is the energy per atom necessary to melt CaF2. (b) The calculated value of d/F when reaching the melting energy versus Ep for irradiations performed at 5, 3 and 0.004 MeV is compared to the experimental ratio d/F = 4.1 nm (dotted line).

To conclude, the required electronic excitation to induce a nano-hillock can be either deposited in the form of electronic energy loss by SHI or via potential energy by slow HCI or both, as in our case. We have shown that there is a clear quantitative linear relation between the increase of Se and the decrease of the deposited Ep, leading to an additive action of the two mechanisms of energy deposition. This relation was quantified in a way that a link between the fraction of potential energy and the depth in which this energy is deposited can be established for CaF2: d (nm) = 4.1 × F. The inelastic thermal spike model applied to describe material modification by Se supplied by SHI has been extended to the potential energy in three-dimensional geometry. Despite the number of parameters that are unknown, it is possible to predict values of the depth and the fraction of deposited potential energy. Measurements of the depth of the molten phase will be a crucial test of the inelastic thermal spike model applied to describe hillock formation by potential energy.

Methods

Preparation of the samples and AFM measurements

CaF2 (111) crystals (Korth Crystal Company) were freshly cleaved in air before placing them in the high vacuum irradiation chamber. After irradiation, samples were imaged under ambient conditions by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) in tapping mode using either a NanoscopeIII (DI) in Lanzhou or a Cypher AFM (Asylum Research) in Vienna. Image analysis was done with the Gwyddion software23. Using statistical methods, this code allows determining the surface roughness and the number of hillocks per unit area for each sample. Freshly cleaved surfaces of CaF2 are flat with a mean roughness of 0.07 nm and no changes are observed when inspected after 5 and 16 days. Consequently, within the experimental errors, the irradiated surface keeps the same roughness over time.

Medium energy irradiations

Irradiations were carried out on the 320 kV ECR platform for highly charged ions physics research at IMP (Lanzhou)38. For each sample, the fluence was about 5 × 1010 Xeq+/cm2. CaF2 surfaces have been irradiated at two kinetic energies (3 and 5 MeV) by Xeq+ with charge states q between 19 and 26. All projectile charge states used were therefore below the charge state threshold for hillock formation reported to be Xe28+ for very low kinetic energy (0.004 MeV)9. In addition, irradiations with Xe30+ ions have been performed at three kinetic energies (0.54, 3 and 5 MeV).

High energy irradiations

Swift heavy Xe ions were delivered by the IRRSUD beam line of the GANIL facility in Caen28. The initial beam energy was 92 MeV and using Al foil degraders, Xe ion energies ranging between 12 and 58 MeV could also be realized. The fluences applied were 5 × 109 Xe/cm2 and 1.5 × 1010 Xe/cm2.

References

Neumann, R. Scanning probe microscopy of ion-irradiated materials. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 151, 42–55 (1999).

Toulemonde, M. & Studer, F. Comparison of the radii of latent tracks induced by high-energy heavy ions in Y3Fe5O12 by HREM, channelling Rutherford backscattering and Mössbauer spectrometry. Phil. Mag. A 58, 799–808 (1988).

El-Said, A. S. Tracks of 30-MeV C60 clusters in yttrium iron garnet studied by scanning force microscopy. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 267, 953–956 (2009).

Barlo Daya, D. D. N. et al. Crater formation due to grazing incidence C60 cluster ion impacts on mica: a tapping-mode scanning force microscopy study. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 124, 484–489 (1997).

Houpert, C., Hervieu, M., Groult, D. & Studer, F. HREM investigation of GeV heavy ion latent tracks in ferrites. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 32, 393–396 (1988).

Benyagoub, A. Mechanism of the monoclinic-to-tetragonal phase transition induced in zirconia and hafnia by swift heavy ions. Phys. Rev. B 72, 094114 (2005).

Studer, F., Hervieu, M., Costantini, J.-M. & Toulemonde, M. High resolution electron microscopy of tracks in solids. Nucl. Intr. Meth. B 122, 449–457 (1997).

Aumayr, F., Facsko, S., El-Said, A. S., Trautmann, C. & Schleberger, M. Single ion induced surface nanostructures: a comparison between slow highly charged and swift heavy ions. J. of Phys. Cond. Matt. 23, 393001 (2011).

El-Said, A. S. et al. Creation of Nanohillocks on CaF2 Surfaces by Single Slow Highly Charged Ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 237601 (2008).

Heller, R., Facsko, S., Wilhelm, R. A. & Möller, W. Defect Mediated Desorption of the KBr(001) Surface Induced by Single Highly Charged Ion Impact. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 096102 (2008).

El-Said, A. S. et al. Phase Diagram for Nanostructuring CaF2 Surfaces by Slow Highly Charged Ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 117602 (2012).

Lake, R. E., Pomeroy, J. M., Grube, H. & Sosolik, C. E. Charge State Dependent Energy Deposition by Ion Impact. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 063202 (2011).

Tona, M., Fujita, Y., Yamada, C. & Ohtani, S. Electronic interaction of individual slow highly charged ions with TiO2 (110). Phys. Rev. B 77, 155427 (2008).

Pomeroy, J. M., Grube, H., Perrella, A. C. & Gillaspy, J. Selectable resistance-area product by dilute highly charged ion irradiation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 073506 (2007).

Winecki, S., Cocke, C. L., Fry, D. & Stockli, M. P. Neutralization and equilibration of highly charged argon ions at grazing incidence on a graphite surface. Phys. Rev. A 53, 4228 (1996).

Lemell, C. et al. On the nano-hillock formation induced by slow highly charged ions on insulator surfaces. Sol. Stat. Elec. 51, 1398–1404 (2007).

Akcoltekin, E. et al. Creation of multiple nanodots by single ions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 290–294 (2007).

Trautmann, C., Klaumunzer, S. & Trinkaus, H. Effect of Stress on Track Formation in Amorphous Iron Boron Alloy: Ion Tracks as Elastic Inclusions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 3648 (2000).

Khalfaoui, N. et al. Characterization of swift heavy ion tracks in CaF2 by scanning force and transmission electron microscopy. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 240, 819–828 (2005).

Ziegler, J. F. & Biersack, J. P. The stopping and ranges of ions in matter, p. 93 from Treatise on Heavy Ion Science, ed. D. A. Bromley (Springer Science and Business media New York 1985).

Grande, P. & Schiwietz, G. Convolution approximation for the energy loss, ionization probability and straggling of fast ions. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 267, 859–865 (2009).

Zhang, Y. W. et al. Damage profile and ion distribution of slow heavy ions in compounds. J. Appl. Phys. 105, 104901 (2009).

Waligorski, M. P. R., Hamm, R. N. & Katz, R. The radial distribution of dose around the path of a heavy ion in liquid water. Nucl. Tracks Meas 11, 309 (1986).

Gervais, B. & Bouffard, S. Simulation of the primary stage of the interaction of swift heavy ions with condensed matter. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 88, 355 (1994).

Toulemonde, M., Assmann, W., Dufour, C., Meftah, A. & Trautmann, C. Nanometric transformation of the matter by short and intense electronic excitation: Experimental data versus inelastic thermal spike model. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 277, 28 (2012).

Nečas, D. et al. Gwyddion, http://gwyddion.net/, (2004) (Date of access: 02/04/2014).

Potential energies of all charge states provided by DREEBIT GmbH company, Dresden, Germany, http://www.dreebit.com/en/ion-beam-technology/scientific-service/ionisation-energies.html, (2008)(Date of access: 31/12/2013).

Grygiel, C. et al. Online in situ x-ray diffraction setup for structural modification studies during swift heavy ion irradiation. Rev. Sci. Instr. 83, 013902 (2012).

Toulemonde, M. et al. Dense and nanometric electronic excitations induced by swift heavy ions in an ionic CaF2 crystal: Evidence for two thresholds of damage creation. Phys. Rev. B 85, 054112 (2012).

Toulemonde, M., Trautmann, C., Balanzat, E., Hjort, K. & Weidinger, A. Track formation and fabrication of nanostructures with MeV-ion beams. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 216, 1–8 (2004).

Toulemonde, M. et al. Reply to “Comment on ‘Dense and nanometric electronic excitations induced by swift heavy ions in an ionic CaF2 crystal: Evidence for two thresholds of damage creation’ ”. Phys. Rev. B 87, 056102 (2013).

Szenes, G. Comment on “Dense and nanometric electronic excitations induced by swift heavy ions in an ionic CaF2 crystal: Evidence for two thresholds of damage creation”. Phys. Rev. B 87, 056101 (2013).

Kost, D., Facsko, S., Möller, W., Hellhammer, R. & Stolterfoht, N. Channels of Potential Energy Dissipation during Multiply Charged Argon-Ion Bombardment of Copper. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 225503 (2007).

Kentsch, U., Tyrroff, H., Zschornack, G. & Möller, W. Retention of the Potential Energy of Multiply Charged Argon Ions Incident on Copper. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 105504 (2001).

Toulemonde, M., Dufour, C., Meftah, A. & Paumier, E. Transient thermal processes in heavy ion irradiation of crystalline inorganic insulators. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 166/167, 903–912 (2000).

Wang, Z. G., Dufour, C., Euphrasie, S. & Toulemonde, M. Electronic thermal spike effects in intermixing of bilayers induced by swift heavy ions. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 209, 194–199 (2003).

Brière, M. A., Schenkel, T., Schneider, D. H., Bauer, P. & Arnau, A. Non-equilibrium energy loss for very highly charged ions in insulators. Phys. Scripta T 73, 324–325 (1997).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. Electron emission and surface etching by slow and medium highly charged ions on HOPG surface”. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 317, 33–36 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (‘973’ Program, Grant No. 2010CB832902), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 11275238, 11275005, 11105192, 91126011 and 11275241), the French-Austrian collaboration SIISU, co-financed by ANR (France, ANR-12-IS04-0005-01) and FWF (Austria, Project No. I 1114-N20), as well as by the French-Chinese cooperation project IiN by PICS-CNRS (France) and NSFC (China, No. 11411130112). We would like to thank the staff from the 320 kV ECR platform at IMP-CAS, the IRRSUD line of the GANIL accelerator and CIMAP laboratory for their help during the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y.W., J.R.S., Y.T.Z., G.Q.X., R.C., X.M.Z., J.R.R., S.D.L., Y.L. and Y.B.S. did the irradiations and AFM analysis of samples irradiated at 320 kV ECR platform for highly charged ions physics research at IMP (Lanzhou). C.G., A.C., I.M. and S.B. did the irradiations and AFM analysis of samples irradiated at IRRSUD beam line of the GANIL facility. R.R., E.G. and F.A. assisted AFM-analysis of samples irradiated at 320 kV ECR platform for highly charged ions physics research at IMP (Lanzhou). C.D., Z.G.W. and M.T. developed the 3D thermal spike model and applied it to insulators and HCI. Y.Y.W., C.G., C.D., F.A. and M.T. have written the paper. Advices have been given by all the authors.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Grygiel, C., Dufour, C. et al. Energy deposition by heavy ions: Additivity of kinetic and potential energy contributions in hillock formation on CaF2. Sci Rep 4, 5742 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05742

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05742

This article is cited by

-

Temperature and energy effects on secondary electron emission from SiC ceramics induced by Xe17+ ions

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Tracing temperature in a nanometer size region in a picosecond time period

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

Synergy of elastic and inelastic energy loss on ion track formation in SrTiO3

Scientific Reports (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.