Abstract

The present study examined neural responses associated with moral sensitivity in adolescents with a background of early social deprivation. Using high-density electroencephalography (hdEEG), brain activity was measured during an intentional inference task, which assesses rapid moral decision-making regarding intentional or unintentional harm to people and objects. We compared the responses to this task in a socially deprived group (DG) with that of a control group (CG). The event-related potentials (ERPs) results showed atypical early and late frontal cortical markers associated with attribution of intentionality during moral decision-making in DG (especially regarding intentional harm to people). The source space of the hdEEG showed reduced activity for DG compared with CG in the right prefrontal cortex, bilaterally in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and right insula. Moreover, the reduced response in vmPFC for DG was predicted by higher rates of externalizing problems. These findings demonstrate the importance of the social environment in early moral development, supporting a prefrontal maturation model of social deprivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Children in foster care and institutional rearing are exposed to early social deprivation, which triggers important delays in physical, cognitive, behavioral and socio-emotional development1,2,3,4. During adolescence, such socio-cognitive impairments persist and may even increase over time5,6,7. One social cognitive ability that proves particularly sensitive to neurodevelopment during adolescence is moral cognition8,9,10. Moral sensitivity (see Introduction within the Supplementary Data) results from complex processes shaped by evolutionary and cultural history11. This domain reflects the complex integration of several psychological processes, including emotion, cognition and mental-state reasoning8,12. In the present study, we examined the neural correlates of an intentional inference task (IIT) indexing rapid moral decision-making in adolescents with early social deprivation.

Brain regions engaged by the IIT8,11 and other moral tasks13,14 include aspects of the posterior superior temporal sulcus [pSTS, also reported as the temporoparietal junction (TPJ)], amygdala, ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), lateral prefrontal cortex (lPFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and insula. Source estimation of high-density electroencephalography (hdEEG) during the IIT has previously shown early engagement of the pSTS, amygdala and vmPFC11. Moreover, the IIT has also been used in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) experiment8. Through effective connectivity analyses, this study demonstrated that, relative to other relevant areas, the amygdala, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) were more sensitive to neurodevelopmental changes through the lifespan.

Institutionalization and early social deprivation produce considerable behavioral and neurophysiological impairments. Behavioral deficits affecting social cognition have been reported in various domains, such as emotion regulation and recognition2,15,16 and theory of mind (ToM)5,17,18. To date, however, the neural correlates of moral sensitivity in adopted or institutionalized children remain unexplored, although this ability seems to be impaired in orphaned adolescents9. Furthermore, physically abused/neglected children show deficits in moral development19. Tentatively, these findings may reflect early deprivation20 and suggest neurodevelopmental changes in moral sensitivity.

Institutionalization impacts the development of neural structures subserving high-level cognition and moral sensitivity, such as the orbitofrontal cortex/vmPFC, infralimbic prefrontal cortex, temporal medial areas, amygdala, lateral temporal cortex and brainstem regions21. Brain connectivity22, volumetric morphometry3,23,24 and electrocortical responses to emotional stimuli25 are atypical in children/adolescents with early deprivation. Atypical patterns of brain activity in deprived individuals suggest a delay in cortical development26, linked to symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity27.

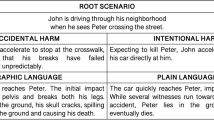

In this study, we used the IIT to investigate the neural correlates of moral sensitivity. We compared the brain responses elicited by morally-laden scenarios in two groups: (i) an early social deprivation group (DG), composed of adolescents (between 11 and 15 years of age) with a background of early social deprivation; and (ii) a control group (CG) matched for age, gender, executive functioning (EF) and educational level. Given that institutionalization can affect domain-general cognitive processes28, we also controlled EF and other basic processes. Additionally, we measured the participants' behavioral deficits to assess subtle effects of institutionalization6,7,29. We used a well-established moral sensitivity paradigm that is modulated by neurodevelopmental changes. This instrument has been validated through hdEEG11 as well as fMRI and eye-tracking measurements8. We recorded hdEEG during the IIT, to evaluate rapid moral decisions regarding actions that results in harming (intentionally or unintentionally) for different target types (object or persons, Figure 1a). The following results were predicted: (1) relative to CG, DG will show abnormal brain responses associated with intentionality attribution in morally-laden scenarios (2) neural responses to the perception of intentional harm vs. unintentional harm, as established through source estimation, will be correlated between groups with different responses in IIT-related brain areas (mPFC, vmPFC, insula and pSTS/TPJ); and (3) individual differences in behavioral disturbances will be predicted by those differential IIT- brain responses.

Stimulus examples and summary of results.

(a) Examples of the visual stimuli used in the study depicting people (top row) or objects (bottom row) being harmed intentionally (left) or by accident (right). The stimuli were short dynamic visual scenarios. (b) Accuracy and reaction times for both groups (CG and DG). (c) ERPs for early and late windows at frontal ROIs for both groups (CG and DG). (d) A significant negative linear association of DG's externalizing problems with a signal change was observed in the right ventromedial prefrontal cortex (r = −.48, p < 0.05). This effect was significant both including all cases (r = −.48, p < 0.05) and after excluding two moderate deviant values (data point 29 and data point 21: r = −.59, p < .05). PI: person intentional; PU: person unintentional; OI: object intentional; OU: object unintentional. Figure 1a is reproduced with permission from Cerebral Cortex8.

Results

Neuropsychological assessment

Both groups showed similar neuropsychological profiles. CG performed better than DG on cube construction (t (35) = 2.15, p < 0.05, two-tailed) and the Trail Making Test B (t (35) = 2.45, p < 0.05, two-tailed). No significant differences between groups were observed for picture arrangement, coding, digits and symbol search, the verbal fluency task, or the Trail Making Test A (see Table 1).

Behavioral problems

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) revealed no significant differences between groups on externalizing (t (35) = 0.27, p = 0.79, two-tailed) and internalizing problems (t (35) = 0.17, p = 0.86, two-tailed).

IIT (behavior)

Accuracy measure. Consistent with previous IIT reports8,11, the principal outcome of this task was an interaction between target type (object vs. person) and intention to harm (intentional vs. unintentional) (F (1,35) = 37.41, p < 0.001). A post-hoc analysis (Tukey HSD, MSE = 46.16, df = 35) showed higher accuracy ratings for person stimuli in intentional (M = 70.01; SE = 4.08) than in accidental (M = 55.02; SE = 2.63) situations (p < 0.001). However, this effect was not observed for objects. No between-group differences were observed (see Figure 1b and Supplementary Data).

IIT (ERPs)

Based on previous reports of ERPs elicited by painful stimuli30,31,32, we selected three regions of interest (ROIs) (at frontal, central and posterior sites) and two time windows (early [within stimulus presentation] and late [after stimulus presentation]) (see Methods).

Early window

All ROIs

An interaction of ROI x intention x group (F (2, 70) = 9.81, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.21) was observed. For CG, as regards the frontal ROI, a post-hoc analysis (Tukey HSD, MSE = 52.49, df = 43.28) showed a trend towards increased activation for intentional harm compared with unintentional harm (p = 0.07). For DG, these effects were non-significant in the frontal ROI, but they did reach significance (and opposite in direction) in the CZ ROI (intentional > unintentional, p = 0.008).

Frontal effects

Given the general effects of ROI (F (2, 70) = 60.64, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.63) and the interactions reported above, we performed separate analyses at the frontal ROI for each group.

In CG, activity was greater for person than object stimuli (target effect F (1, 17) = 5.81, p = 0.02, η2 = 0.25). We also observed an interaction of target x intention (F (1, 17) = 2.26, p = 0.15, η2 = 0.31). Post-hoc comparisons of person stimuli (Tukey HDS, MSE = 56.93, df = 17) showed enhanced responses for intentional than unintentional scenarios (p = 0.024).

For its own part, DG exhibited no significant effects of intention or target (or interactions) at the frontal ROI (see Figure 1c and 2).

ERPs for all conditions and groups.

Frontal, central and posterior ROIs showing the different category modulations for both CG and DG. When the effects of condition and group were analyzed without considering the ROI variable (not shown in the figure), in both groups person intentional (PI) stimuli elicited enhanced activation relative to person unintentional (PU), but the CG exhibited a trend toward increased activation of intentional compared with unintentional stimuli. More importantly, when separate ROIS analyses were performed (as detailed in the figure), in frontal ROIs, CG had increased amplitudes for person intentional (PI) compared with person unintentional (PU). This effect was absent in DG.

Late window

Late-window effects were very similar to those observed in the early window. See Supplementary Data for details.

Source space

Early window

A comparison of the relevant category (person intentional) between groups showed significantly higher activity for CG than DG (Figure 3a) in the right PFC (t = 309.14, p < 0.01), left vmPFC (t = 98.38, p = 0.02) and right vmPFC (280–300 ms: t = 110.85, p = 0.01). In addition, tendencies of higher activity for CG than DG were observed in the left PFC (200–270 ms, t = 33.16, p = 0.06) and at an earlier latency in the right vmPFC (140–200 ms: t = 32.85, p = 0.06), as shown in Figure 3c.

Source-space comparison of PI in CG and DG.

(a and b) Differences in cortical activation between CG (red) and DG (blue) in z-scores. Panel (a) shows the peak difference in the early time window (150–300 ms), while panel (b) shows the peak difference in the late time window (600–800 ms). Panels (c) and (d) show significant differences in cortical activation between groups in z-scores. The values shown are averages over subjects and time. During the early time window (c), significantly higher activity for CG relative to DG was observed in the right prefrontal cortex (PFC) and both the left and the right ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). During the late time window (d), significantly higher activity for CG relative to DG was observed in the right PFC, left and right vmPFC and right insula. vmPFC: ventromedial prefrontal cortex; PFC: prefrontal cortex.

Late window

Enhanced activation (Figure 3b) for CG than DG was also observed in the right insula (t = 148.09, p < 0.01), the right PFC (600–700 ms: t = 309.14, p < 0.01; and 700–800 ms: t = 52.99, p = 0.03), the left vmPFC (t = 121.54, p < 0.01) and the right vmPFC (t = 234.17, p < 0.01). Finally, a trend towards greater activity in CG relative to DG was observed in the left PFC (t = 34.83, p = 0.05) and the left anterior temporal lobe (left ATL, t = 26.75, p = 0.07), as shown in Figure 3c.

Association between source estimation and behavioral problems (CBCL)

No effects were observed for both groups regarding significant z scores (brain sources of person intentional stimuli) and behavioral scores (CBCL). Nevertheless, DG exhibited a significant inverse relationship between CBCL (externalizing factor) and z scores from the right vmPFC (combining both early and late windows) (r = −.48, p < 0.05), as shown in Figure 1d.

Discussion

The effects of early social deprivation on cognitive development have been widely studied in children and adolescents. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, no study has examined the neural correlates of moral sensitivity in these populations. Moral development involves a fundamental social adaptation and is crucial for successful social functioning in families, peer groups and other environments19. Early childhood deprivation has been associated with maladaptive behaviors and social problems, including maladjustment, impulse control and rule breaking7,29. In this study, we assessed the neural correlates of moral sensitivity in adolescents with early social deprivation using an ecologically valid non-verbal task while controlling for EF and educational level. In this group (DG), we observed atypical early/late cortical markers associated with intentionality attribution during moral decision-making, particularly those regarding intentional situations involving persons. Importantly, the source space for the latter condition showed that activation patterns were reduced for DG than controls in the right PFC, bilateral vmPFC and right insula. Additionally, activation of the right vmPFC was inversely correlated with behavioral problems in DG. These results indicate that individuals with a background of early social deprivation exhibit atypical brain activity when processing moral information in the prefrontal cortex. This is the first demonstration that early social deprivation affects late neurodevelopment in the domain of moral decision-making.

Immature development of the prefrontal cortex1,26,27 has been associated with early-life stressful experiences and social deprivation. Also, the vmPFC has been linked to moral judgments33,34,35 but not to capacities for general intelligence, logical reasoning, or declarative knowledge35,36. Importantly, the vmPFC is critical to process affective responses shaped by conceptual information about specific outcomes37. These results are consistent with our findings that DG exhibited atypical neural responses in the context of preserved general cognitive skills.

The neural modulation of intentionality and target categories observed in CG is consistent with previous EEG/ERPs results11. At both early (~200 ms) and late (~600 ms) time windows, modulations were strongest for scenarios depicting intentional harm to people. Previous studies have shown that situations depicting intentional harm lead to differential activation of the amygdala/temporal pole and vmPFC11. Conversely, in DG, evoked neural responses (mainly at frontal ROIs) failed to discriminate rapid moral sensitivity to scenarios involving intention to harm. Unlike controls, DG showed no neural facilitation for person intentional situations in frontal regions. Neural facilitation in the vmPFC is critical when affective responses are shaped by conceptual information about specific outcomes37. Early social deprivation has negative consequences on emotional capacities in late development4,18. This would explain why CG and not DG, exhibited stronger modulation for stimuli conveying intentional harm to people. The absence of stronger cortical activity in DG when viewing intentional harm to people suggests an immaturity in the neurocognitive mechanism supporting moral sensitivity. Therefore, our results parallel reports of delayed frontal lobe maturation in institutionalized children26,27.

Source space analysis showed DG's reduced activation in the right PFC, bilateral vmPFC and right insula. These regions are engaged by the IIT and are in typically developing children strongly associated with the affective component of moral decision-making8,11. Also, our results are consistent with the neurodevelopmental effects observed in the right PFC and the bilateral vmPFC in institutionalized children21. Note that reduced (late-window) activation in the insula and bilateral vmPFC has been previously linked to immature emotional regulation and delayed frontal maturation in children within deprivation contexts27. Building upon this empirical background, our results indicate that social deprivation has specific effects on the development of the neural substrates underlying moral sensitivity.

No significant differences in behavioral problems were found between DG and CG. This replicates previous findings in studies comparing adopted adolescents and controls38. However, for the DG, in our study, externalizing problems (e.g., delinquent and aggressive behaviors) were negatively associated with brain activity in the right vmPFC: the lesser the vmPFC activation, the higher the behavioral problems. Such a correlation aligns well with studies implicating the right vmPFC as a crucial region for emotional regulation and decision making39,40,41 and with reports of maladaptive social behaviors subsequent to vmPFC lesions33,42. In a similar vein, juvenile psychopaths with callous-unemotional traits present atypical fronto-central neural dynamics of affective arousal during empathy-for-pain processing, coupled with relative insensitivity to first-hand physical pain43. Taken together, these previous findings and our present results suggest a delayed maturation of the PFC regions involved in moral sensitivity and externalizing problems.

No significant between-group differences were found for the behavioral measures of moral sensitivity. This is consistent with previous IIT studies reporting that all participants (age range 4–37) were able to distinguish between intentional and unintentional actions. Given the straightforwardness of the task, moral judgment involving evaluation of intentional or unintentional harm did not vary as a function of age8,11. Young children as early as 3 years old are capable to detect intentionality during moraly-laden tasks44. However, the IIT is sensitive to changes in neurodevelopment, as it reveals differential activation and functional connectivity patterns across age8,11. In this sense, our study showed that early social deprivation does not affect the accuracy of the IIT, but it does have neurodevelopmental effects.

Using a neuropsychological battery, we controlled for the influence of basic cognitive impairment on moral decision-making. With these measures, we ensured that DG included only high-functioning individuals (participants with strong cognitive deficits were excluded). We found only subtle differences in neuropsychological outcomes associated to visuomotor abilities and cognitive flexibility, as previously reported in other studies with institutionalized children1,5,28. In growing up, our DG participants received social and affective support from their adoptive families. As compared with institutional rearing, foster care induces improvement in cognitive abilities45, which would explain why our participants exhibited neither cognitive impairments nor strong behavioral problems.

Understanding the intentions behind a harmful action in an interpersonal context is both a cognitive and an emotionally-laden task. It involves ToM46 processing of the perpetrator's and the victim's behaviors as well as the ability to empathize47. Both ToM and empathy are high-level mechanisms engaging several neural and psychological sub-components46,47. They depend on the individual's social experiences and involve a contextual dialogue between the emotions and intentions of others48. These mechanisms can be learned. In fact, certain forms of therapy imply training in these domains. Relative to their home-raised counterparts, children growing in socially deprived environments usually receive less attention from their caregivers. Consequently, they are less frequently exposed to situations requiring an understanding of the intentions and emotions of others, or even of themselves. Therefore, it is plausible that our DC participants exhibited a weaker maturation of the brain areas underpinning emotion regulation (vmPFC, insula) and ToM (vmPFC, PFC).

Our study is the first report of atypical neural processing of moral sensitivity in socially deprived children. However, several lines of research need to be addressed in future studies. Admittedly, our sample size was moderate. However, it is not smaller than that of previous studies on social deprivation3,21,22. Our sample size is partially explained by the restricted recruitment procedures and the inclusion of only high-functioning participants in DG. A previous study using the IIT with EEG has proven sensitive with data obtained with less than 10 participants11. Nevertheless, future studies may consider recruiting larger samples through the inclusion of participants with different degrees of cognitive impairment. A second limitation is the limited information about pre-adoptive care, which is a common issue for adopted participants23,49. For instance, we lacked data regarding prenatal risk factors, such as prenatal nutrition, maternal stress during pregnancy, or prenatal exposure to alcohol. The role of these prenatal and postnatal antecedents in moral cognition should be assessed in future studies. Finally, both the impairment profiles and the efficacy of intervention strategies in socially deprived participants should be assessed using sensitive measures of frontal maturation and moral cognition.

In conclusion, the present study constitutes a novel experimental approach to examine moral sensitivity in socially deprived adolescents. Specifically, it brings together ecologically valid non-verbal stimuli and simple, efficient measures of relevant neurodynamic signatures. While different aspects of basic cognitive delay associated with early social deprivation have been reported previously, our study offers pioneering evidence of atypical brain activity underlying moral sensitivity with spared basic cognitive domains. Our data, obtained from combining EEG/ERPs, source space and brain-behavior associations, support a prefrontal maturation model of social deprivation. Such findings offer new insights into the neurodevelopment of morality50,51 after social deprivation, thus opening promising avenues for further research.

Methods

Participants

The present study was conducted in the context of the Attachment & Adoption Research Network (AARN), an international project focusing on adopted adolescents [http://aarnetwork.wordpress.com/]. Our sample included two groups: (i) DG participants, who had experienced early social deprivation of at least 6 months (18 reared in institutional care and 2 reared in foster care) and (ii) CG participants, namely, non-adopted adolescents who grew up in their biological families (N = 20). Three cases (DG = 1, CG = 2) were later excluded because of excessive artifacts in the EEG recordings. DG consisted of 19 adopted adolescents (9 females) between 11 and 15 years of age. Their mean age was 12.58 years (SD = 1.3) and their mean adoption age was 30.05 months (SD = 21.68; range = 6–72 months). The adopted adolescents were recruited from the following Chilean adoption agencies: Servicio Nacional de Menores (SENAME), Fundación Chilena para la Adopción and Fundación San José para la Adopción. CG was composed of 18 adolescents reared by their biological parents (8 females). The mean age for both groups was 12.56 years (SD = 1.3). CG was recruited from social networks (e.g., Facebook groups and chain letters). We controlled for differences in age (t (35) = 0.052, p = 0.96), sex (χ2(1) = 0.24, p = 0.62) and education level (t (35) = 0.30, p = 0.77) between the groups. The participants had no history of physical or mental disorders, as assessed through a neuropsychiatric interview with the parents and the institutions' records. Parents and adolescents gave informed consent in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile approved all experimental procedures.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)52. We used the CBCL to assess the adolescent's behavior, emotional problems and relevant symptoms. Parents completed a 120-item questionnaire indicating whether a behavior was (0) “not”, (1) “a little/sometimes” or (2) “often/clearly” typical of their child. The Total Problems score consists in the sum of the scores of eight sub-scale syndromes. Some are combined in the following two total sub-scales: internalizing (withdrawn, anxious/depressed behavior and somatic problems) and externalizing (delinquent and aggressive behavior). The CBCL is the most common assessment of general behavioral problems in studies of the adopted population6,7,29.

Neuropsychological assessment

All participants completed a neuropsychological battery assessing attention, speed processing, visual-spatial abilities and EF. In the verbal fluency task, participants were given a category or a letter and asked to state all of the words that came to mind in one minute. In the digit-span subtest53, participants were asked to repeat a given set of numbers in the same order (forward digit-span) or in the reverse order (backward digit-span). The block-design task53 required participants to arrange cubes with red, white, or red and white sides to form a specific pattern. For the picture-arrangement task53, participants were required to piece together a misarranged story into the correct order. In the symbol-search task53, participants were asked to decide whether a given symbol was present in a line-up of other symbols. The coding subtest53 involved using a key of symbols to decipher a numerical code. To measure attention and speed processing, we incorporated the trail-making test54, which entailed connecting numbers (test A) or letters and numbers (test B) that were randomly aligned on a sheet of paper.

Intention inference task (IIT)

EEG signals were recorded while participants completed a modified version of a standard IIT developed by Decety and colleagues8 for neurodevelopmental studies of empathy and morality. The IIT assesses rapid moral decisions regarding actions involving harm to others (intentional vs. unintentional) with different target types (object vs. person). Participants were asked to evaluate whether the actions they had seen were performed intentionally or unintentionally11. In our study, participants were presented with a series of three-frame videos on a computer screen. The first frame (T1) was 100-ms long and displayed an establishing scene. The second frame (T2) was a 100 ms frame denoting either intentional or unintentional harm. This was followed by a third 100-ms frame (T3), confirming the intentional or unintentional harm. The trials began with a fixation cross presented for 800 ms. A 500 ms inter-trial interval was added. During the experiment, accuracy and reaction times were recorded. There were 184 trials (46 per condition: Person Intentional, Person Unintentional, Object Intentional and Object Unintentional). The percentage of preserved trials after ICA correction was always >87% for each category.

Procedure

Once the family was contacted, all participants and their parents signed a consent form. Afterwards, we conducted an interview with each the mother of each adolescent. First, we tested the participants with a neuropsychological battery to assess general cognitive processes. While the participants performed the IIT, we recorded the EEG.

EEG recordings and preprocessing

EEG signals were recorded with HydroCel Sensors from a GES300 Electrical Geodesic amplifier at a rate of 500 Hz using a system of 129-channels. Data that were outside a 0.1 Hz to 100 Hz frequency band were filtered out during the recording. Later, the data were further filtered using a band-pass digital filter with a range of 0.3 to 30 Hz to remove any unwanted frequency components. During recording, the vertex was used as the reference electrode by default, but signals were re-referenced offline to average electrodes. Two bipolar derivations were designed to monitor vertical and horizontal ocular movements (EOG). Continuous EEG data were segmented during a temporal window that began 200 ms prior to the onset of the stimulus and concluded 800 ms after the offset of the stimulus. Eye-movement contamination and other artifacts were removed from further analysis using both an automatic (ICA) procedure and a visual procedure. No differences were observed between groups regarding the number of trials. All conditions yielded a percentage of artifact-free trials that was at least 80%.

ERP preprocessing and analysis

For ERPs, we used a strategy of channel selection based on the observed effects (also previously reported in ERP studies of empathy31,32). The time-course analysis for three representative ROIs (FZ, CZ and PZ) involving six adjacent electrodes (see Supplementary Data) was included as an additional within-subject ANOVA factor (electrode). We considered mean amplitude values. An early window before the end of stimulus presentation (150–300 ms) was selected to track the early automatic responses. A late window (600–800 ms) corresponds to the time-window effects observed in a previous report of the ITT11 with T1 stimuli presented by 500 ms. The onset was marked at the T2 stimulus onset and reliable effects were observed after 200 ms (equivalent to 600–800 ms windows in our design).

Data analysis

A Student's t-test was used to compare the demographics and the neuropsychological and behavioral problems across groups. Repeated ANOVAs and Tukey HSD post-hoc comparisons (when appropriate) were performed to analyze behavioral IIT, reaction time and ERP data (we included a measure of effect size, namely, partial eta (η2)). Source reconstruction analysis was tested with two-tailed t-tests using permutations to generate the null hypothesis distribution (for details, see Supplementary Data). The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was computed to evaluate the association of behavioral outcome (CBCL) with source space brain correlates of the relevant category (person intentional).

Source reconstruction analysis

Cortical current density mappings of ERPs for the intentionally-harmed-persons condition were reconstructed using the BrainStorm package55. The forward model was calculated using the Open MEEG Boundary Element Method56 on the cortical surface of a template MNI brain (colin27 atlas) with a 1-mm resolution. The inverse model was constrained using a weighted minimum-norm estimation (wMNE)57 to estimate source activation in picoampere-meters (pA.m). For each subject, an absolute average over trials was computed for each condition. These activation values for each participant and condition were normalized by calculating the z-scores of the primarily computed average relative to the baseline activity within the −200 to 0 ms window. These z-scores were used to plot cortical maps and to extract the ROIs that were visually identified in the cortical maps.

Several scouts (BrainStorm jargon for the ROIs that are defined as a subset of vertices of the surface) were selected from two different atlases58,59. In addition, some scouts were manually constructed using the BrainStorm toolbox to improve surface segmentation. Selection of the ROIs for source analysis was based on previous fMRI8 and evoked magnetic field studies that reported the neural generators of empathy-related processes and the ERPs that were presently analyzed. Based on previous studies of moral evaluations and empathic responses, we expected to observe major activity in the vmPFC, dlPFC, pSTS, amygdala and insula for the intentionally-harmed-persons condition8,11. Based on a prior study60, we expected higher activity in the vmPFC, dlPFC and amygdala for CG than DG and higher activity in the right pSTS/TPJ for DG than CG. We expected these effects to occur in two different time windows: an early time window between 150 and 300 ms after stimulus onset and a late time window between 600 and 800 ms after stimulus onset. For more details about the source reconstruction and statistical analysis, see Supplementary Data.

References

Pollak, S. D. et al. Neurodevelopmental effects of early deprivation in postinstitutionalized children. Child Dev. 81, 224–236 (2010).

Vorria, P. et al. The development of adopted children after institutional care: a follow-up study. J Child Psychol Psyc 47, 1246–1253 (2006).

Mehta, M. A. et al. Amygdala, hippocampal and corpus callosum size following severe early institutional deprivation: the English and Romanian Adoptees study pilot. J Child Psychol Psyc 50, 943–951 (2009).

Tarullo, A. R., Garvin, M. C. & Gunnar, M. R. Atypical EEG power correlates with indiscriminately friendly behavior in internationally adopted children. Dev Psychol. 47, 417–431, 10.1037/a0021363 (2011).

Colvert, E. et al. Do theory of mind and executive function deficits underlie the adverse outcomes associated with profound early deprivation?: findings from the English and Romanian adoptees study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 36, 1057–1068 (2008).

Bimmel, N., Juffer, F., van IJzendoorn, M. H. & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. Problem behavior of internationally adopted adolescents: A review and meta-analysis. Harvard Rev Psychiat 11, 64–77 (2003).

Wierzbicki, M. Psychological adjustment of adoptees: A meta-analysis. J Clin Child Psychol 22, 447–454 (1993).

Decety, J., Michalska, K. J. & Kinzler, K. D. The contribution of emotion and cognition to moral sensitivity: a neurodevelopmental study. Cereb Cortex 22, 209–220 (2012).

Carlo, G., Koller, S. & Eisenberg, N. Prosocial moral reasoning in institutionalized delinquent, orphaned and noninstitutionalized Brazilian adolescents. J Adolescent Res 13, 363–376 (1998).

Carlo, G., Fabes, R. A., Laible, D. & Kupanoff, K. Early adolescence and prosocial/moral behavior II: The role of social and contextual influences. J Early Adolesc 19, 133–147 (1999).

Decety, J. & Cacioppo, S. The speed of morality: a high-density electrical neuroimaging study. J Neurophysiol 108, 3068–3072 (2012).

Decety, J. & Howard, L. H. The role of affect in the neurodevelopment of morality. Child Dev Perspect 7, 49–54 (2013).

Decety, J. & Porges, E. C. Imagining being the agent of actions that carry different moral consequences: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia 49, 2994–3001 (2011).

Moll, J., De Oliveira-Souza, R. & Zahn, R. The neural basis of moral cognition: sentiments, concepts and values. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1124, 161–180, 10.1196/annals.1440.005 (2008).

Fries, A. B. W. & Pollak, S. D. Emotion understanding in postinstitutionalized Eastern European children. Dev Psychopathol. 16, 355–370 (2004).

Barone, L. & Lionetti, F. Attachment and emotional understanding: a study on late-adopted pre-schoolers and their parents. Child Care Hlth Dev 38, 690–696 (2012).

Yagmurlu, B., Berument, S. K. & Celimli, S. The role of institution and home contexts in theory of mind development. J Appl Dev Psychol 26, 521–537 (2005).

Tarullo, A. R., Bruce, J. & Gunnar, M. R. False Belief and Emotion Understanding in Post-institutionalized Children. Soc Dev 16, 57–78 (2007).

Koenig, A. L., Cicchetti, D. & Rogosch, F. A. Moral development: The association between maltreatment and young children's prosocial behaviors and moral transgressions. Soc Dev 13, 87–106 (2004).

Maughan, B. & McCarthy, G. Childhood adversities and psychosocial disorders. Brit Med Bull 53, 156–169 (1997).

Chugani, H. T. et al. Local brain functional activity following early deprivation: A study of postinstitutionalized Romanian orphans. Neuroimage 14, 1290–1301 (2001).

Eluvathingal, T. J. et al. Abnormal brain connectivity in children after early severe socioemotional deprivation: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Pediatrics 117, 2093–2100 (2006).

Tottenham, N. et al. Elevated amygdala response to faces following early deprivation. Dev Sci 14, 190–204 (2010).

Sheridan, M. A., Fox, N. A., Zeanah, C. H., McLaughlin, K. A. & Nelson, C. A. Variation in neural development as a result of exposure to institutionalization early in childhood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 12927–12932 (2012).

Moulson, M. C., Fox, N. A., Zeanah, C. H. & Nelson, C. A. Early adverse experiences and the neurobiology of facial emotion processing. Dev Psychol. 45, 17–30 (2009).

Marshall, P., Fox, N. & Bucharest Early Intervention Project Core, G. A comparison of the electroencephalogram between institutionalized and community children in Romania. J Cognitive Neurosci 16, 1327–1338 (2004).

McLaughlin, K. et al. Delayed maturation in brain electrical activity partially explains the association between early environmental deprivation and symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiat 68, 329–336, 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.005 (2010).

Cardona, J. F., Manes, F., Escobar, J., López, J. & Ibáñez, A. Potential consequences of abandonment in preschool-age: Neuropsychological findings in institutionalized children. Behav Neurol 25, 291–301, 10.3233/BEN-2012-110205 (2012).

Hawk, B. & McCall, R. B. CBCL behavior problems of post-institutionalized international adoptees. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 13, 199–211, 10.1007/s10567-010-0068-x (2010).

Fan, Y. T., Chen, C., Chen, S. C., Decety, J. & Cheng, Y. Empathic arousal and social understanding in individuals with autism: evidence from fMRI and ERP measurements. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 10.1093/scan/nst101 (2013).

Ibanez, A. et al. Subliminal presentation of other faces (but not own face) primes behavioral and evoked cortical processing of empathy for pain. Brain Res 1398, 72–85, 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.05.014 (2011).

Decety, J., Yang, C.-Y. & Cheng, Y. Physicians down-regulate their pain empathy response: an event-related brain potential study. Neuroimage 50, 1676–1682 (2010).

Anderson, S., Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D. & Damasio, A. Impairment of social and moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci 2, 1032–1037, 10.1038/14833 (1999).

Koenigs, M. et al. Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgements. Nature 446, 908–911, 10.1038/nature05631 (2007).

Saver, J. & Damasio, A. Preserved access and processing of social knowledge in a patient with acquired sociopathy due to ventromedial frontal damage. Neuropsychologia 29, 1241–1249, 10.1016/0028-3932(91)90037-9 (1991).

Koenigs, M. & Tranel, D. Irrational economic decision-making after ventromedial prefrontal damage: evidence from the Ultimatum Game. J Neurosci 27, 951–956, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4606-06.2007 (2007).

Roy, M., Shohamy, D. & Wager, T. D. Ventromedial prefrontal-subcortical systems and the generation of affective meaning. Trends Cogn Sci 16, 147–156, 10.1016/j.tics.2012.01.005 (2012).

Juffer, F. & van IJzendoorn, M. H. Behavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees. JAMA-J AM MED ASSOC 293, 2501–2515 (2005).

Bechara, A., Tranel, D. & Damasio, H. Characterization of the decision-making deficit of patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions. Brain 123, 2189–2202 (2000).

Bechara, A. et al. Decision-making deficits, linked to a dysfunctional ventromedial prefrontal cortex, revealed in alcohol and stimulant abusers. Neuropsychologia 39, 376–389 (2001).

Clark, L. et al. Differential effects of insular and ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions on risky decision-making. Brain 131, 1311–1322 (2008).

Beer, J., Heerey, E., Keltner, D., Scabini, D. & Knight, R. The regulatory function of self-conscious emotion: insights from patients with orbitofrontal damage. J Pers Soc Psychol 85, 594–604, 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.594 (2003).

Cheng, Y., Hung, A.-Y. & Decety, J. Dissociation between affective sharing and emotion understanding in juvenile psychopaths. Dev Psychopathol. 24, 623–636, 10.1017/S095457941200020X (2012).

Vaish, A., Carpenter, M. & Tomasello, M. Young children selectively avoid helping people with harmful intentions. Child Dev. 81, 1661–1669 (2010).

McDermott, J. M. et al. Psychosocial deprivation, executive functions and the emergence of socio-emotional behavior problems. Front Hum Neurosci 7, 167, 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00167 (2013).

Allison, T., Puce, A. & McCarthy, G. Social perception from visual cues: role of the STS region. Trends Cogn Sci 4, 267–278 (2000).

Decety, J. & Jackson, P. L. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev 3, 71–100, 10.1177/1534582304267187 (2004).

Ibanez, A. & Manes, F. Contextual social cognition and the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 78, 1354–1362, 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182518375 (2012).

Roskam, I. et al. Another way of thinking about ADHD: the predictive role of early attachment deprivation in adolescents' level of symptoms. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1–12 (2013).

Decety, J. & Howard, L. H. in Handbook of Moral Development (eds Killen, M. & Smetana, J.) 454–474 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates., 2013).

Decety, J. The neuroevolution of empathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1231, 35–45 (2011).

Achenbach, T. Manual for the CBCL/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry (1991).

Wechsler, D. Wechsler intelligence scale for children–Fourth Edition (WISC-IV). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation (2003).

Partington, J. E. & Leiter, R. G. Partington's Pathways Test. Psycholog Serv Bull 1, 9–20 (1949).

Tadel, F., Baillet, S., Mosher, J. C., Pantazis, D. & Leahy, R. M. Brainstorm: a user-friendly application for MEG/EEG analysis. Comput Intell Neurosci 2011, 879716, 10.1155/2011/879716 (2011).

Gramfort, A., Papadopoulo, T., Olivi, E. & Clerc, M. OpenMEEG: opensource software for quasistatic bioelectromagnetics. Biomed Eng Online 9, 45, 10.1186/1475-925X-9-45 (2010).

Baillet, S. et al. Evaluation of inverse methods and head models for EEG source localization using a human skull phantom. Phys Med Biol 46, 77–96 (2001).

Destrieux, C., Fischl, B., Dale, A. & Halgren, E. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. Neuroimage 53, 1–15, 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.010 (2010).

Desikan, R. S. et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 31, 968–980, 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021 (2006).

Escobar, M. J. et al. Attachment patterns trigger differential neural signature of emotional processing in adolescents. PLoS One 8, e70247, 10.1371/journal.pone.0070247 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a doctoral grant from CONICYT to M.J.E., as well as by grants CONICYT/FONDECYT Regular (1130920 and 1140114), Foncyt-PICT 2012-0412 and Foncyt-PICT 2012-1309, CONICET and the INECO Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.I., M.J.E. designed the experiment; A.R. programmed the experiment; M.J.E., D.H., A.R., A.C., A.I. conducted the experiments; M.J.E., D.H., J.D., L.S., M.K.M., S.B., A.R., A.C., D.G., J.S., F.M., V.L., A.I. analyzed the data; M.J.E., D.H., J.D., L.S., M.K.M., S.B., J.P.M., J.S., F.M., V.L., A.I. wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary data

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Escobar, M., Huepe, D., Decety, J. et al. Brain signatures of moral sensitivity in adolescents with early social deprivation. Sci Rep 4, 5354 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05354

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05354

This article is cited by

-

Socialisation approach to AI value acquisition: enabling flexible ethical navigation with built-in receptiveness to social influence

AI and Ethics (2023)

-

Children’s Criminal Perception; Lessons from Neurolaw

Child Indicators Research (2022)

-

Changing characteristics of the empathic communication network after empathy-enhancement program for medical students

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Increased moral condemnation of accidental harm in institutionalized adolescents

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Empathy for others’ suffering and its mediators in mental health professionals

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.