Abstract

Study design:

Questionnaire survey.

Objectives:

Although a range of novel therapeutic approaches for traumatic spinal cord injury (tSCI) are being trialled in highly standardised, pre-clinical research models, little has been published about the extent of standardisation in health service delivery for newly injured tSCI patients.

Setting:

All Emergency Medical Services (EMSs) and 11 level-1 trauma centres (L1TCs) in the Netherlands.

Methods:

A survey assessing the organisation of pre-hospital and acute tSCI management was developed and distributed across all 23 pre-hospital EMSs and 11 L1TCs based in the Netherlands.

Results:

Response rates for EMSs and L1TCs were 82 and 100%, respectively. Thirteen EMSs (68%) transported all patients who are suspected of having tSCI to L1TCs. The decision to transfer tSCI patients to L1TCs was primarily made by paramedics at the scene of accident (79%). Nonetheless, no EMS reported the use of validated neurological assessments for determining the likelihood of tSCI. The International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI were used to determine the level and severity of tSCI in four centres, and three centres performed magnetic resonance imaging in all tSCI patients. Three L1TCs had spinal cord perfusion support protocols in place, and two centres administered methylprednisolon to acute tSCI patients.

Conclusion:

We found a large variance in the delivery of pre-hospital and acute tSCI management in a well-defined geographical catchment area. This survey urges the need for implementing standardised assessments and developing best-practice guidelines, which should be endorsed by all pre-hospital and acute tSCI health-care providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In Western countries, the incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury (tSCI) is estimated to be 10 per million to 83 per million per year.1, 2 In the Netherlands, the incidence is between 11 and 16 per million per year.1, 2 The injury’s primary impact on the cord starts a sequence of biochemical and ischaemic processes that contribute to a progressive damage of the cord tissue.3 This process is commonly known as the secondary injury. Acute phase management of tSCI (both pre-hospital and in-hospital acute phase treatment) concentrates on prevention and mitigation of this secondary injury.

In recent years, there have been a number of trials evaluating both pre-hospital and in-hospital acute phase management of tSCI patients.4, 5, 6, 7 Research in pre-hospital management has focused on evaluation of symptoms by paramedics and timely referral to a specialised SCI centre.4, 8 As signs of tSCI are often difficult to recognise in an acute trauma situation, it is important that the emergency medical personnel is trained to recognise possible signs of tSCI and treat patients accordingly.4 Timely referral of (suspected) tSCI patients to a specialised SCI centre has been shown to reduce complications and improve outcome.4, 8 Daily practice has shown, however, that practical and logistical problems occasionally prevent ambulances from referring patients to the most appropriate hospital.8 In-hospital acute care management of tSCI patients has mostly been focused around early hospital interventions, including surgical decompression of the spinal cord6, 7, 9 and spinal cord perfusion pressure support.5, 10 Both interventions have been associated with the prevention secondary injury and functional recovery. However, these interventions have mostly been studied in highly standardised (pre-) clinical trials.

It is unclear whether the results of trials looking at pre-hospital and in-hospital treatment of newly injured tSCI patients have properly been implemented in daily clinical practice. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the consistency of pre- and in-hospital acute phase care for patients with (suspected) tSCI among Emergency Medical Services (EMSs) and level-1 trauma centres (L1TCs) across the Netherlands.

Materials and Methods

Development of survey

In the Netherlands, the protocol of the regional pre-hospital EMSs recommends that patients with possible traumatic SCI are referred to a L1TC.11, 12 A survey was developed to assess the organisation and the level of standardisation of tSCI treatment in EMSs and L1TCs in the Netherlands. EMSs in the Netherlands are responsible for all pre-hospital ambulance care for a specific region. L1TCs in the Netherlands are no specialised tSCI centres but general trauma centres with neurosurgery, orthopaedic surgery and trauma surgery facilities.

Questions were based on the recommendations made in the international guideline of tSCI,13 the national guideline for ambulance care,12 the national guideline on vertebral fractures11 and the tSCI pathway of the Dutch SCI patient society.14 The questionnaire was then evaluated by all authors (which included an orthopaedic surgeon, rehabilitation physician and head of an EMS), and their recommendations were used to improve the questionnaire.

Administration of survey

The final survey consisted of two parts: part A was aimed at EMSs and included questions regarding the diagnosis of tSCI in an acute situation by paramedics and regarding the referral procedures of patients with suspected tSCI (Appendix 1), whereas part B was designed for physicians in L1TCs and consisted of questions regarding different aspects of in-hospital acute phase management of tSCI: logistics, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up (see Appendix 2). The survey was sent to all 23 EMSs and 11 L1TCs in the Netherlands between December 2012 and April 2014. If no response was received from a specific recipient, several reminders were sent.

Results

EMS survey

The response rate for the EMS survey was 82% (N=19). All EMSs reported that their standard policy was to primarily transport patients with (suspected) tSCI to a L1TC. When asked whether this policy was adhered to in daily practice, 13 EMSs answered that tSCI patients are always transported to an L1TC. Two EMSs reported that only definitively diagnosed tSCI patients are always transported to an L1TC, three EMSs reported that they do not transport (suspected) tSCI patients to an L1TC when the patient has unstable vital parameters and one centre reported that in daily practice they did not always refer these patients to an L1TC. Asked whether the EMSs were aware of the fact that early surgery can improve the outcome in tSCI patients, seven EMSs reported that they did not know this. The decision whether or not to transport a patient with (suspected) tSCI to an L1TC was made by the attending paramedics in 15 EMSs (79%). Although several different tests were reported for diagnosing tSCI in an out-of-hospital emergency setting (Table 1), none of these were validated neurological assessments.

L1TC survey

The response rate of the L1TC survey was 100%. Two centres reported that they had combined their SCI management protocols and are therefore presented as one centre in our results.

Logistics

On average, the centres reported 10–15 new patients with tSCI per year (Table 2). Six trauma centres use protocols for the acute phase management of tSCI patients; the remaining centres endorsed general traumatology protocols. In eight centres, there were 4–6 surgeons (trauma surgeons, orthopaedic surgeons or neurosurgeons) performing stabilisation and decompression surgery. In one centre, there were over 10 surgeons who performed this type of operation.

All centres started rehabilitation (physical therapy and occupational therapy) after surgery. All centres reported to start mobilisation as soon as patients were able to. All trauma centres referred their SCI patients to nearby specialised spinal cord rehabilitation centres. The average length of stay in the trauma centres, as reported in the survey, ranged from 7 to 56 days.

Diagnosis

For assessing the severity of the injury during the acute phase in the emergency room, six centres reported they use a regular neurological examination (not further specified). Four centres used the International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI (ISNCSCI) (Table 3).15 Spinal cord compression and progressive neurologic deterioration was determined using physical examination in seven L1TCs and using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in three L1TCs. Three centres perform an MRI scan at admission as part of their standard procedure. The other seven centres perform MRI scans only at indication.

Treatment

Five centres have protocols for the type and timing of spine surgery (Table 4). In the other five centres, there were no protocols, and the type and timing of spine surgery were based on the experience and opinion of the attending spine surgeon. In eight centres, spinal cord decompression is performed within at least 24 h after injury; two centres do not always perform acute decompression within 24 h, except when there is a deterioration of neurological function. In two L1TCs, decompression was considered a protocolled emergency procedure.

A blood pressure management protocol was present in three trauma centres, and this protocol recommended keeping mean arterial pressure above 80 mm Hg. Two centres reported to administer methylprednisolone as standard treatment according to the NASCIS protocol of 5.4 mg kg−1h−1 within 8 h after injury, and all other centres reported that they did not administer methylprednisolone after tSCI.

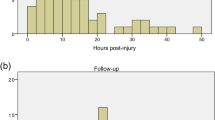

Follow-up

The interviewed surgeons did not follow up the neurological function or performed only a basic neurological examination in outpatient clinic visits (Table 5). The start of the involvement of rehabilitation physicians in the treatment of tSCI patients ranged from arrival of the patient in the emergency room to within 1 week after admission.

Discussion

In this study, large differences were found regarding pre- and in-hospital care of tSCI in a well-defined geographical catchment area. A large variety of criteria were used by Dutch EMSs to diagnose tSCI in an out-of-hospital emergency setting. Although all EMSs agree that all suspected tSCI patients should be referred to a L1TC, 32% of the EMSs reported that they do not always do so. Only six of the 10 L1TCs use strict acute phase management protocols that include recommendations according to international tSCI guidelines. In three L1TCs, spinal cord decompression is not performed within 24 h after injury. Blood pressure augmentation to prevent neurogenic shock is performed in only three L1TCs. Two L1TCs administer methylprednisolone as a standard treatment.

Earlier studies showed that, in western countries, paramedics are usually able to properly assess a possible tSCI8 and the need to transport patients to a specialised tSCI centre.4, 16 In our survey, there was a large consensus among EMSs on the need to transport patients to an L1TC, even though several respondents reported that this was not always possible in daily practice, partly because of logistics. If ambulances have to drive a large distance to an L1TC, they cannot be used for other emergencies in the region. Another factor that was mentioned as a comment by several EMSs was that whether tSCI was part of a multi-trauma influenced their decision to refer a patient to a L1TC. When a patient was haemodynamicaly instable, the EMSs often referred patients to the hospital that was nearest to the accident. A large variety in the criteria used to determine a (suspected) tSCI was found, with none of the EMSs using a specific validated tSCI assessment. The Revised Trauma Score, which was used most often, does not cover SCI at all.17 Even though it is understandable that in emergency situations a thorough assessment of a possible tSCI is difficult, the potential delay and decrease in patient outcome when transporting these patients to conventional emergency care centres16 demonstrates the need for national consensus and guidelines.

In this survey, large differences in acute phase management of tSCI patients in L1TCs were found. We could roughly identify two groups. The first group used strict tSCI protocols regarding several aspects of acute phase management including early spinal cord decompression, neurogenic shock treatment and regular neurological evaluation with standardised tests (for example, ISNCSCI). The second group did not have a strict protocol for acute phase management of SCI. In this second group, there was no standard use of an internationally applied neurological assessment (for example, ISNCSCI), decompression was not necessarily performed in a 24-h window after injury and no standard neurogenic shock prevention was in place. Earlier studies also found differences in protocols for tSCI patients and showed that these differences, especially in timing of decompression, can influence outcome in tSCI patients.18, 19

There are several reasons for the differences in acute care protocols for tSCI patients. The level of evidence of most studies that look at acute phase interventions is relatively low. Because of this, recommendations made in international guidelines are often inconclusive.13 This leaves room for individual physicians to deviate from these guidelines. Another reason for the differences between L1TCs is the fact that there is currently no nationwide protocol for acute phase management of tSCI patients in the Netherlands. The lack of a nationwide protocol can be attributed to several factors. tSCI has a low incidence, which means that there is little to no routine in the treatment of this patients. In the Netherlands, the treatment of tSCI is further divided over 10 L1TCs. When combining the estimates of tSCI incidence with the number of surgeons performing surgery in the acute phase of tSCI as reported in the survey, a total of 64 surgeons operate roughly 185 tSCI patients per year. This means that each surgeon only treats a few patients per year, which reduces the urgency for making a comprehensive protocol. The surgical treatment of tSCI patients in the Netherlands has traditionally been divided among different departments. This was confirmed by our survey, which found that decompression and stabilisation were performed by orthopaedic surgeons, neurosurgeons and trauma surgeons, sometimes even within the same hospital. Finding consensus among these different disciplines to establish a protocol could be difficult. To address the fragmentation of tSCI care in the Netherlands, the Dutch SCI patients’ society (Dwarslaesie Organisatie Nederland) has published a Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury Pathway supported by the national organisations of orthopaedic surgeons, neurosurgeons, trauma surgeons and rehabilitation physicians, with recommendations for acute phase management of tSCI.14

Study limitations

The two surveys we performed only provided an indication of the consistency in pre-hospital and in-hospital care of tSCI patients. There were no exact measurements of variables such as the incidence of tSCI and the number of patients who underwent surgical decompression within 24 h after injury. As these surveys consisted of open questions, there is bias from the respondents who could give desirable answers to provide a more positive picture. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the different aspects of acute tSCI care are directly related to the quality of tSCI treatment and patient outcome.20 Whether or not the regional differences as found in this study could have resulted in differences in outcome of tSCI cannot be elucidated.

Conclusion

A survey was held in all L1TCs and 19 EMSs in the Netherlands to evaluate the current state of pre-hospital logistics and in-hospital acute phase management of tSCI patients. Among EMSs, there appeared to be a general consensus on the need to transport all (suspected) tSCI patients to an L1TC, although this is not always realised. There was a large variety in assessing tSCI in an emergency setting between the EMSs. The results from the L1TC survey indicate that there is a large variety between L1TCs in acute phase management of tSCI patients, even in a well-defined geographical area. The results from this survey show the need for standardisation of assessments and the development of guidelines endorsed by all pre-hospital and in-hospital health-care providers who are involved in the acute phase treatment of tSCI patients.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Van Asbeck FW, Post MW, Pangalila RF . An epidemiological description of spinal cord injuries in The Netherlands in 1994. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 420–424.

Wyndaele M, Wyndaele JJ . Incidence, prevalence and epidemiology of spinal cord injury: what learns a worldwide literature survey? Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 523–529.

Kakulas BA . A review of the neuropathology of human spinal cord injury with emphasis on special features. J Spinal Cord Med 1999; 22: 119–124.

Ahn H, Singh J, Nathens A, MacDonald RD, Travers A, Tallon J et al. Pre-hospital care management of a potential spinal cord injured patient: a systematic review of the literature and evidence-based guidelines. J Neurotrauma 2011; 28: 1341–1361.

Bracken MB . Steroids for acute spinal cord injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 1: CD001046.

Fehlings MG, Vaccaro A, Wilson JR, Singh A, W Cadotte D, Harrop JS et al. Early versus delayed decompression for traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: results of the Surgical Timing in Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study (STASCIS). PLoS One 2012; 7: e32037.

Van Middendorp JJ, Hosman AJ, Doi SA . The effects of the timing of spinal surgery after traumatic spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurotrauma 2013; 30: 1781–1794.

Middleton PM, Davies SR, Anand S, Reinten-Reynolds T, Marial O, Middleton JW . The pre-hospital epidemiology and management of spinal cord injuries in New South Wales: 2004-2008. Injury 2012; 43: 480–485.

Vale FL, Burns J, Jackson AB, Hadley MN . Combined medical and surgical treatment after acute spinal cord injury: results of a prospective pilot study to assess the merits of aggressive medical resuscitation and blood pressure management. J Neurosurg 1997; 87: 239–246.

Van de Meent H, Vos PE, Schreuder HW, van der Hoeven JG . [Acute traumatic spinal cord injury and cardiovascular complications due to neurogenic shock: a possible threat for functional recovery]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2004; 148: 1103–1106.

CBO NOV en K voor de G. Richtlijn acute traumatische wervelletsels: opvang, diagnostiek, classificatie en behandeling [Internet] 2009. http://www.diliguide.nl/document/946/file/pdf/.

Nederland A . Landelijk Protocol Ambulancezorg 7.2 [Internet] 2011. http://www.ambulancezorg.nl/nederlands/pagina/1724/landelijk-protocol-ambulancezorg—lpa-7.2-.html.

Hadley MN, Walters BC, Grabb PA, Oyesiku NM, Przybylski GJ, Resnick DK et al. Guidelines for the management of acute cervical spine and spinal cord injuries. Clin Neurosurg 2002; 49: 407–498.

Nederland DO . Zorgstandaard Dwarslaesie (Internet) 2013. http://www.zorgstandaarden.net/zza/media/upload/pages/file/ZD%2520versie%2520consultatieronde%25200612.pdf.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 535–546.

DeVivo MJ, Kartus PL, Stover SL, Fine PR . Benefits of early admission to an organised spinal cord injury care system. Paraplegia 1990; 28: 545–555.

Gilpin DA, Nelson PG . Revised trauma score: a triage tool in the accident and emergency department. Injury 1991; 22: 35–37.

Tuli S, Tuli J, Coleman WP, Geisler FH, Krassioukov A . Hemodynamic parameters and timing of surgical decompression in acute cervical spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30: 482–490.

Mirza SK, Krengel WF 3rd, Chapman JR, Anderson PA, Bailey JC, Grady MS et al. Early versus delayed surgery for acute cervical spinal cord injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999; 359: 104–114.

Van Weert KC, Schouten EJ, Hofstede J, van de Meent H, Holtslag HR, van den Berg-Emons RJ . Acute phase complications following traumatic spinal cord injury in Dutch level 1 trauma centres. J Rehabil Med 2014; 46: 882–885.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Translated version of the survey part A

Survey pre-hospital care for patients with (suspected) tSCI

In the Dutch national protocol ambulance care (Landelijk Protocol Ambulancezorg, version 7.2, March 2011) it is recommended that all patients with loss of neurological function have to be transported to a Level 1 Trauma Center (L1TC).

With this survey we want to investigate whether this recommendation is possible in daily practice and what are the factors that influence if a patient with (suspected) tSCI is transported to an L1TC or to the nearest hospital.

-

1

Are there agreements in your region about the destination (L1TC or nearest hospital) of patients with suspected tSCI?

-

2

When in the triage (via phone with the centralist or by the ambulance paramedics) of patients with (suspected) tSCI is it decided whether or not a patient is referred to an L1TC?

-

3

Do you transport all patients with (suspected) tSCI directly to an L1TC? If not, what is the reason to not refer these patients to an L1TC?

-

4

Do you register how often patients with tSCI receive pre-hospital care in your region? If so, do you register which percentage of patients with (suspected) tSCI is referred to an L1TC?

-

5

Does your EMS use a standard test to diagnose SCI in an emergency setting? If so, which test?

-

6

Is it known within your EMS that early surgery can improve outcome in tSCI patients?

Appendix 2

Translated version of the survey part B

Survey acute phase management of tSCI in Level 1 trauma centers

Logistics

-

1

What is the estimated yearly incidence of tSCI in your hospital?

-

2

Is there a specific hospital-wide protocol for the acute phase treatment of tSCI patients?

-

3

How many surgeons perform decompression in your hospital?

Diagnosis

-

1

Which method is used to assess the severity of the injury in tSCI patients?

-

2

Is an emergency MRI standard performed in all tSCI patients?

-

3

What are the criteria used to determine compression of the spinal cord?

-

4

Are ISNCSCI scores taken pre- and post-surgery?

Treatment

-

1

Is there a protocol in your hospital for the surgical treatment of tSCI patients?

-

2

What is the time window in which cord decompression has to be performed?

-

3

Is decompression an indication for emergency surgery?

-

4

Do all tSCI receive standard neurogenic shock treatment?

-

5

Do tSCI patients have a set value for Mean Arterial Pressure?

-

6

Are tSCI patients given methylprednisolone as part of standard treatment?

Follow-up

-

1

Do you have a protocol for the prevention and treatment of complications of tSCI?

-

2

What is the average length of stay of tSCI patients?

-

3

When are tSCI patients allowed to start mobilisation?

-

4

At which point in the acute phase treatment is the rehabilitation physician involved?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fransen, B., Hosman, A., van Middendorp, J. et al. Pre-hospital and acute management of traumatic spinal cord injury in the Netherlands: survey results urge the need for standardisation. Spinal Cord 54, 34–38 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.111

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.111

This article is cited by

-

Development of a comprehensive assessment tool to measure the quality of care for individuals with traumatic spinal cord injuries

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2023)

-

Standard set of network outcomes for traumatic spinal cord injury: a consensus-based approach using the Delphi method

Spinal Cord (2022)